The article below by Dr. Michael David Magee entitled “Hebrew Goddesses & Origin of Judaism” was originally posted in the CAIS website under the broader topic of “Persia and the creation of Judaism“. The version printed below has a number of minor edits, otherwise it is the same article as posted in the CAIS website.

As in the CAIS website, Kavehfarrokh.com does not necessarily condone or endorse the views presented in Dr. Magee’s article. The objective is the provision of information, ideas and discourse for learning/educational purposes pertaining to antiquity and ancient Iran.

Readers are encouraged to forward questions and/or comments by e-mail regarding the below article to at: [email protected]

Kindly note that excepting those images cited and posted direclty from CAIS, all other images/pictures/illustrations (and accompanying descriptions for these) inserted below did not appear in the original article by Dr. Magee and the later CAIS posting of Dr. Magee’s article.

====================================================================

In pre-historic and primitive societies in which men and women are segregated into their own living quarters, and children live with the women, it is not surprising that women are seen as dominant and provide the image of the supreme being. To children, women were the source of sustenance and discipline. Men were mainly out of sight, following their own vain pursuits and the concept of father did not exist. Any of the men could have been the father of a child but no one ever knew which was. All children knew their mother and a mother knew her own children, but all women had the nurturing and caring role of mother, and there were enough for all children to be treated equally. So God was a goddess for myriads of years.

When we come to Judaism and then Christianity, women have almost gone out of sight. Both religions have a masculine God and no goddess, masculine priests and no priestesses. Christianity also has a masculine son of God and what appears to be a masculine Holy Ghost. This trio constitutes the Christian “mystery” of the Trinity, but the logic of any such trinity is to have a father god, a mother god and a baby son god. Where, oh where has the mother god gone?

The Egyptian Trinity (right to left): Goddess Isis, Osiris (Isis’ husband) and their son Horus, statuette (housed at the Louvre Museum, Paris, France) from the 22nd Egyptian Dynasty (943-716 BCE) (Source: Guillaume Blanchard, July 2004, Fujifilm S6900 for Public Domain).

The Egyptian Trinity (right to left): Goddess Isis, Osiris (Isis’ husband) and their son Horus, statuette (housed at the Louvre Museum, Paris, France) from the 22nd Egyptian Dynasty (943-716 BCE) (Source: Guillaume Blanchard, July 2004, Fujifilm S6900 for Public Domain).

The answer is that it was expunged by the Persian administrators who set up the Jewish religion—in the image of Zoroastrianism—in the fifth century BC. Zoroaster had abolished all gods except one—Ahura Mazda—and some angels and demons of various descriptions, around two centuries before. Now that the Persians were conquering the world, they thought it a good idea to have everyone on earth subject to one God of Heaven, whatever his local name might have been, to match the one king of earth—the king of kings of Persia. Since the only God of Heaven had manifestly approved the appointment of the Persian king, everyone would recognize it as an unchallengeable divine appointment, and peace would reign!

Family squabbles could not be admitted into this scheme, and so goddesses were written out of sacred history. Of course, no Jew or Christian will accept this because they have accepted the propaganda that there is only one, masculine god, and, if it was ever different, it was because people were ignorant! Only the Jews were not ignorant because they had been specially selected by God in the time of Abraham, about 2000 BC to carry out His plan for human religious revelation. Unfortunately for all this, the Jews, or rather their predecessors often called Hebrews, did worship goddesses as even the Jewish scriptures admit! But, they were only the backsliders who refused to accept God’s word—for thus the Persian “restorers” of Judaism painted the inhabitants of the land into which the Persians transported the “returners from exile”.

Painting by a contemporary American artist Minerva Teichert showing the Jews celebrating the arrival of Cyrus the Great (r. 549–530 BCE) who liberates them for the return to Jerusalem. When Cyrus conquered Babylon, he ordered the sacred religious objects of the Jerusalem Temple to be restored to their rightful owners, the Jews.

Painting by a contemporary American artist Minerva Teichert showing the Jews celebrating the arrival of Cyrus the Great (r. 549–530 BCE) who liberates them for the return to Jerusalem. When Cyrus conquered Babylon, he ordered the sacred religious objects of the Jerusalem Temple to be restored to their rightful owners, the Jews.

The truth, as scholars know but do not publicly divulge, is that the religion of the people in the Hill Country of Palestine before the Persians arrived was recognizably the same religion as that of everyone else who lived in the Levant and its hinterland. The richer parts of the eastern Mediterranean left plentiful archaeological remains in the form of clay tablets, most famously at Ugarit, that tell us a lot about ancient Canaanite religions and their practice. The people here were called Canaanites and they worshipped a pantheon of gods and goddesses, led by the supreme god, El, and his wife, Athirat (Asherah) and their son, Baal Hadad.

Stele dated to 5th-13th century BCE (housed at the Louvre Museum, Paris, France) discovered at the acropolis of Ras Shamra (ancient Ugarit) which depicts Baal with Thunderbolt (Source: Photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen for Public Domain). In the Caananite religions, Baal Hadad was the offspring of the supreme god El and his wife, Athirat (Asherah).

Canaanite Religion

The paucity of archaeological remains from the Hill Country confirm the picture underlying the bible stories—the practices of the small population that lived there were the same as their neighbors. The accessible gods were called Baal, meaning Lord, just as Yehouah is habitually called and actually translated as Lord (Yehouah Elohim, Lord God). The Persians admitted one god only and eventually Yehouah prevailed, but it seems that bodies of people for some time preferred other gods, notably El (Elohim). The Canaanite title for their son of god, Baal, was vilified by the “restorers” as the name of all false gods, whatever their real name, Hadad, Eshmun, Dagon, Milcom or whatever, and that is what we find in the bible.

Reading the bible carefully tells us that three goddesses were worshipped in the Hill Country later called Israel and Judah. The three were Asherah, Astarte and the Queen of Heaven. Possibly the latter is the title of one or both of the other two, but all three are mentioned, and the Queen of Heaven was so loved that the people refused Jeremiah’s pleas to turn from her to Yehouah!

Unknown 8,000 year-old ancient goddess from Anatolia from the ancient site of Catal Hoyuk, modern Turkey (Source: Photo by Stanisław Nowak for Public Domain). Housed in the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations (Ankara, Turkey), the Çatal Hüyük mother goddess of Anatolia may have been a prototype “Queen of Heaven”. It is now agreed by mainstream scholars that Goddesses were held in high esteem in the ancient Near East, Anatolia, the Indus Valley and the Mediterranean.

Unknown 8,000 year-old ancient goddess from Anatolia from the ancient site of Catal Hoyuk, modern Turkey (Source: Photo by Stanisław Nowak for Public Domain). Housed in the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations (Ankara, Turkey), the Çatal Hüyük mother goddess of Anatolia may have been a prototype “Queen of Heaven”. It is now agreed by mainstream scholars that Goddesses were held in high esteem in the ancient Near East, Anatolia, the Indus Valley and the Mediterranean.

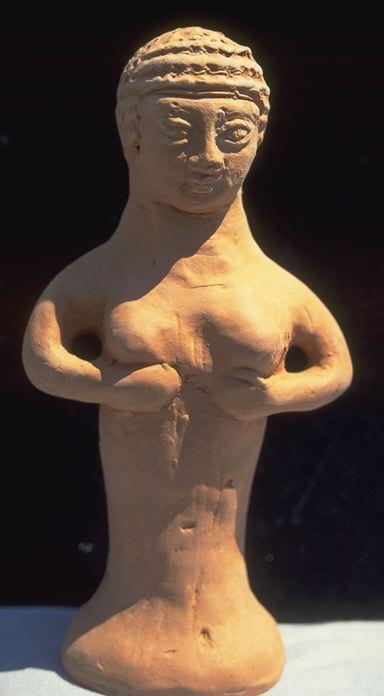

Hundreds of small, mainly female figurines often of terracotta are found all over Palestine, many dated to the period of the supposed divided monarchy from 900 to 600 BC. Of these figurines of goddesses, some are Astarte from the symbolism, and they can be dated from 2000 BC to the capture of Jerusalem when they cease. Some Christian and Jewish “scholars” try to make out that these figurines are not goddesses at all but are magical talismans or primitive pornography, being models of prostitutes, but it is impossible to imagine that they do not have some ritual significance and must therefore be images of a goddess.

The images that seem identifiable with Astarte come in the form of plaques that seem to show a recess within which the image is displayed and therefore suggest that they are models of an image in a shrine. The plaques are impressed in terracotta using a mold and show the goddess with upraised arms holding serpents or lilies or both, though sometimes she holds her abdomen and sometimes has her hands by her sides. Often she is standing on the back of a lion. Her hair is dressed in the flicked style, looking rather like ram’s horns, typical of the Egyptian goddess Hathor, who had been popular in the south of the country—many of these plaques have been excavated at Devir near Hebron. In the Iron Age period, the preferred form of the goddess was that of an elongated bust, looking like a head and shoulders on a pillar, and therefore looking more phallic like the presumed Asherahs.

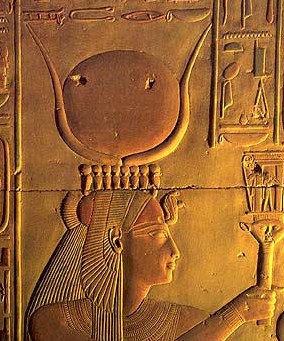

Egyptian goddess Hathor (Source: TourEgypt).

Commentators try to claim they are not Israelite but Canaanite, the two types of people living side by side for hundreds of years. Honest scholars today are asking how these populations can be so surely distinguished. All of the cultural evidence is that there was only one population. The need for two only arises to explain how what is read in the bible differs from what happened according to the evidence. So, only the need to fulfill biblical expectations makes anyone think that there were two different peoples in Palestine at this time. And the people that lived there were Canaanites who worshipped Baal and several goddesses.

Asherah

Asherah was the Canaanite Venus, the Goddess of the Sea and the Mother of All the Gods. A lot is known about her from the Ugarit tablets that go back to the fourteenth century BC. She was the wife of the supreme god, El, whence her alternative name, Elath, the Goddess.

A terracotta figurine of Asherah housed at the National Maritime Museum of Israel in Haifa (Source: Devor Avi of the Elef Millim Project Trip for Public Domain).

A terracotta figurine of Asherah housed at the National Maritime Museum of Israel in Haifa (Source: Devor Avi of the Elef Millim Project Trip for Public Domain).

Semitic deities commonly have two names, or rather a name and a title, and are known by either. The parallelism that characterizes Semitic verse might be the reason for the perpetuation of this habit, if not its origin, thus:

He cries to Asherah and her children,

To Elath and the company of her offspring.A stele has an inscription, “Qudsu Astarte Anat”, suggesting that Qudsu was a name or title of Anat who is herself identified with Astarte. Asherah and Qudsu also appear in the parallelism of Semitic verse where Asherah says in one place:

I myself have not a house like the gods

A court like the sons of Qudsu,

and elsewhere:He came to qds

Athirat of the Tyrians.

“Qudsu” (“qds”), the same as the biblical “qadesh” or “kadesh”, means “holy” or “sacred”, or the “Holy One”, or “Sacred One”. Moreover, the biblical Asherah is given as Ashtaroth in the plural, seemingly a plural of Astarte, though another plural is a masculine one, Asherim, doubtless part of the patriarchal plan to eliminate any hint of female deities. Asherim is conventionally translated as “groves”. The Sumerians had a goddess called Ashratim who was also the consort of their supreme god, Anu, and so she is likely to be an earlier and perhaps the original epiphany of Asherah.

Asherah is also mentioned in the Amarna letters from fourteenth century BC Egypt. They are records of reports and correspondence from Egyptian officials and emissaries outside the country, and so are an importance resource. They show that already Asherah was either being confused with Astarte or the two goddesses were always the same one, differently named. The names are used interchangeably in the Amarna tablets. The letters make it clear that her worshippers regarded themselves as her “slaves”. To this day Christians accept that they are “slaves” of God, although they wrongly translate the Greek for “slaves” as “servants”.

Asherah was, then, a goddess known throughout the Fertile Crescent, but not according to traditionalists for God’s plan, in Judah or Israel—at least officially. The seventeenth century translators of the King James Version of the bible hid the goddess quite from the view of the faithful by translating “Asherah” as “grove”. Judges 3:7 admits that Baal and Asherah were worshipped in Israel (and God of course punished the Israelites for it). The goddess, Asherah, is actually mentioned forty times in the scriptures.

Several passages in the scriptures describe Asherahs being built or torn down, or uprooted. It seems they were pillars, usually of wood, occasionally of stone, effectively phallic symbols but of the form of a woman, though in Micah 5:14, they are masculine and therefore surely phallic objects. In fact, each locality had its shrine to the goddess and doubtless had local peculiarities, so that we read in the Amarna letters of the “Asherah of here” and the “Asherah of there”, some of which might have been tree trunks still rooted in the earth, others of which were set up under trees and others of which were set up on the “high places”.

Judges 6:25,28 says they also stood next to the altars of Baal, suggesting that Asherah was thought of as the consort or mother of Baal, and 2 Kings 21:7 and 23:6 admit they stood in the Jerusalem temple. None of these Asherahs have survived, because they were deliberately destroyed by the priests of the Ezra school and its successors. But the terracotta dolls mentioned above seem likely to be household models of the full sized Asherahs, so we can get an idea of them.

In the scriptures, the stories about Asherah worship, the constant destruction and reintroduction of the symbols of the goddess, simply show the immense popularity she had among the Am ha Eretz (indeed the name “Am ha Eretz”, usually understood to be the men of the land, the simple folk, might well be intended to signify Mother Earth.

In Jewish myth, Asherah worship was first introduced by women, the wife of Solomon or the wife of Ahab, the latter being the infamous Jezebel. The prophet Elijah took exception to the prophets of Baal and defeated them in a gratuitous show of supernatural power on Mount Carmel, but the prophetesses of Asherah seem to have been left to continue their practices. Prophetess might have been used in the accepted sense here because a fifteenth century BC Akkadian text speaks of a “wizard of Asherah” forecasting the future, so Asherah might have had a reputation for fortune telling.

An ancient depiction of Asherah (Source: The Queen of Heaven).

The Asherah of Samaria, supposedly set up by Ahab for Jezebel (1 Kgs 16:33), was still standing a hundred years later. Indeed, the impression is that the devotion of the people to Asherah was constant while the devotion to the male god fluctuated between Baal and Yehouah. Since, notwithstanding the fact that Asherah was properly the Mother of the Gods, she was also the consort of Baal or Yehouah—both mere sprogs of the supreme god—Asherah remained the female deity whichever of the male sons of god took precedence.

Bearing in mind the passages about the Queen of Heaven in Jeremiah, the reason why the shrines to Baal kept getting torn down might have been because Baal was the Lord (Baal) Yehouah, being pressed on to the Am ha Aretz by the priests of Yehouah, and being rejected repeatedly by the people who were devotees of the Goddess. The destruction of the sanctuaries to Baal therefore meant the destruction of the sanctuaries to Baal Yehouah. When the Yehouists eventually asserted their power at the beginning of the fourth century BC, the scriptural stories were anachronistically altered to suit the Yehouists.

Be that as it may, the scriptures record that the worshippers of this god of the Jews and Christians, Yehouah, invited all of the worshippers of Baal to a solemn assembly for their god at his sanctuary in Samaria, fitted them out in fresh vestments, then murdered them every one! The shrines to the bull god in Dan were not destroyed however and nor were the shrines to Asherah. If Yehouah was the only god allowed, one can only conclude that he was identified with the bull god and the goddess was his consort. In the story of the Exodus, the Israelites worshipped images of a bull, and a bull was a symbol of fertility.

The presence of the Asherah in Samaria for so long was made the mythical reason why the state of Israel was lost to the Assyrians, together with the ten lost tribes of Israel, but this is propaganda to justify the worshippers of Yehouah at Jerusalem—the Jews—hating the worshippers of Yehouah in Samaria—the Samaritans. In fact, the scriptures credit the king of Judah, Joshiah, with “burning” the Samaritan Asherah about forty years before Jerusalem was finally sacked by the Babylonians. This was about a hundred years after Israel had supposedly ceased to exist and its people had been deported to be lost forever. In truth, it was probably only after the Persian administrators had imposed monotheism that the goddess was harmed, and the Asherah of Samaria destroyed.

Figurine of Asherah in the Hecht Museum of Israel (Source: Pinterest).

In Judah, Ashtaroth are not mentioned at all, but king Asa finds it necessary to destroy them, so they must have been there all the time. His son, Jehoshaphat however, finds he has to destroy them all again! His son, Joash allowed them back and even placed an Asherah in the Jerusalem temple where it remained until the pious monarch, Hezekiah removed it over a hundred years later (2 Kgs 18:4). Hezekiah also destroyed a brass serpent that Moses had given the Israelites to worship! Hezekiah’s son, Manasseh, restored the Asherah but not the brass snake, despite it having been a gift of the great Israelite leader.

The Book of Deuteronomy was then found, supposedly lost and forgotten since the time of Moses, but discovered “by accident” in the time of king Josiah, just 35 years before Jerusalem was conquered by the Babylonians. Plainly, the book was written by the returning “exiles” sent by the Persian king, who pretended that this law book had been discovered before they had even appeared on the scene. It forbade the building of Asherahs and pillars and had been just the sort of thing that would motivate a good Yehouist as Josiah was depicted as being. Yet, despite it, if Jeremiah is taken to be historical, the people still preferred the goddess and he later found himself defending Yehouah against the Queen of Heaven!

Anath

Anath was the sister of Baal Hadad and the daughter of Asherah in Canaanite mythology, and was identified with Astarte (Hebrew, Ashtoreth). She seems also to be Anahita, the later Persian goddess.

An Astarte plaque showing the goddess Astarte or Anath holding lilies or lotuses (Source: CAIS).

It is curious to the modern mind why goddesses should be distinguished then evidently confused or conflated again, and it seems more than likely that the patriarchal religious leaders divided the original Great Mother Goddess into her aspects to weaken her, but the people effectively refused to see all the goddesses thus created as anything other than what they were—the Great Mother. Thus, Anath, Astarte and Asherah might have had different names but were seen as the same. We saw from the Amarna letters and the bible itself that Asherah was confused with Ashtoreth. The ancient tablets, using the Semitic parallelism mentioned above, have:

Whose fairness is like Anath’s fairness;

Whose beauty is like Ashtoreth’s beauty.

The two goddesses are equated in these lines of verse, and such parallels led foreigners, the Egyptians for example, to think that here were two separate goddesses, whose equality must have meant they were sisters. According to Albright, however, Ramesses III called Anath and Astarte, his shield (singular) suggesting that he knew they were one goddess only.

Anath (Anthat, Anaitis) was a goddess of war and love in the Ugaritic tablets, a virgin goddess yet promiscuous and vicious. Anath’s main lover was her brother, Baal Hadad, with whom she had intercourse by taking the form of a heifer. Baal is therefore a bull, just as Yehouah was at Dan and Bethel, and in the wilderness. As a war goddess she is ferocious, killing wildly and with glee until she has to wade in blood and gore, rather like the Indian goddess, Kali, also known as Annapurna. She has characteristics almost identical to those of Inannu of Sumeria and Ishtar of Akkadia who were called “Lady of Heaven” and “Mistress of the Gods”, just as Anath and Astarte were in Egypt.

Ashtoreth refers to the womb, an appropriate reference for a fertility goddess, but one which shows that it is a descriptive title of the goddess Anath—Anath of the Womb, one could call her according to Raphael Patai (PAT-THG). Anath is often also called the “maiden”, so, although a womb, she is a virgin. The Egyptians described them as the goddesses “who conceive but do not bear” because they were permanently virgins. Ashtoreth was also a goddess of war as the scriptures declare also when the Philistines offered Saul’s armour in the temple of Ashtoreth (1 Sam 31:10) presumably as a token of appreciation for her assistance in the battle.

Anath is not mentioned in the scriptures and Ashtoreth or Astarte are mentioned only nine times, but she was much more important than such a small number of citations suggests. In Judges 2:13 and 10:6, Astarte and the Ashtaroth are respectively mentioned in conjunction with Baal, as warnings to the Israelites. Solomon is similarly warned by Yehouah (1 Kgs 11:5,33) for adopting Ashtoreth and other foreign gods.

Figure of Babylonian Goddess Ereshkigal or her sister Ishtar dated to 1800-1750 BCE (Source: Aiwok for Public Domain). The figure was previously thought to be that of Lilith but modern scholarship suggests her to be Ishtar or Ereshkigal.

Anath does appear in the scriptures as the place names Beth Anath and Anathoth or Anatha (even today still called Anata), the birthplace of Jeremiah, amongst others. Anathoth is simply the plural of Anath, a convention among the Hebrews in naming towns. Thus Ashtaroth, the plural of Ashtoreth is also a place name. These names arose because they were the place of a shrine (a house or “beth”) for the deity, and were therefore the place where the deity’s devotees lived—the Anaths (Anathoth) or the Astartes (Ashtaroth). One of the Judges, according to the scriptures, was a “son of Anath”, taken by the fathful to be literally true, but merely disguising that he was a follower or devotee of Anath.

Queen of Heaven

Jeremiah tried to persuade the Israelite worshippers of the Queen of Heaven in Egypt to turn to Yehouah but they refused. Anath and Astarte were “Lady (Lady being the feminine of Lord, therefore meaning “ruler”) of Heaven” throughout the Near East, including Egypt. The people, in reply, think it is not through any neglect of Yehouah that they have had misfortune but because of their neglect of the goddess!

“As for the word that thou hast spoken unto us in the name of the Lord, we will not hearken unto thee. But we will certainly do whatsoever thing goeth forth out of our own mouth, to burn incense unto the queen of heaven, and to pour out drink offerings unto her, as we have done, we, and our fathers, our kings, and our princes, in the cities of Judah, and in the streets of Jerusalem: for then had we plenty of victuals, and were well, and saw no evil. But since we left off to burn incense to the queen of heaven, and to pour out drink offerings unto her, we have wanted all things, and have been consumed by the sword and by the famine.

And when we burned incense to the queen of heaven, and poured out drink offerings unto her, did we make her cakes to worship her, and pour out drink offerings unto her, without our men?” Jeremiah 44:16-19

Elsewhere in Jeremiah, the author adds more detail:

“Seest thou not what they do in the cities of Judah and in the streets of Jerusalem? The children gather wood, and the fathers kindle the fire, and the women knead their dough, to make cakes to the queen of heaven, and to pour out drink offerings unto other gods, that they may provoke me to anger.” Jeremiah 7:17-18

These are small windows into the genuine religion of Palestine before the Persians altered it. The author, clearly a propagandist for the Persian “returners” from “exile”, admits to the longstanding practice of the cities of Judah, and of Jerusalem itself. Their fathers—meaning in the first passage, ancestors, not just their immediate dads—their kings and princes had burnt incense to the Queen of Heaven and poured libations for her (the equal of the wine of the Eucharist). The women add that they made cakes for her (the equal of the Eucharist wafer), and insist that they did not worship the goddess only as a female indulgence but did it with their menfolk. The earlier passage in Jeremiah shows that the whole practice was communal.

Clay figurine of an ancient Mother Goddess of the Yarmukian Culture of the Neolithic era (Source: Yaels for Public Domain). Dated to 7,500 years ago, this figurine was discovered at the Sha’ar Hagolan kibbutz, situated to the south of the sea of Galilee.

Clay figurine of an ancient Mother Goddess of the Yarmukian Culture of the Neolithic era (Source: Yaels for Public Domain). Dated to 7,500 years ago, this figurine was discovered at the Sha’ar Hagolan kibbutz, situated to the south of the sea of Galilee.

The cakes will have been made in molds just like the molds used to cast the terracotta figures of the goddess, found everywhere, or perhaps the terracotta figurines were themselves used to make an impression on the cakes, which were then baked and eaten or burnt as an offering. That the Queen of Heaven was Ashtoreth is suggested by the use of these cakes, because an ancient Babylonian text to Ishtar refers to sacrificial cakes using a name that seems to be cognate with the Hebrew word.

The people had been happy and well fed under the care of the goddess, but latterly had suffered hardship under the Babylonians and then the Persian administrators’ efforts to bring in an exclusive new god, the Persian version of Yehouah. No one intelligent can read books like Jeremiah, Isaiah, Ezekiel and other prophetic books without seeing them as propagandist pseudepigraphs written by the schools of Nehemiah and Ezra to persuade the native Palestinians to adopt the monotheistic religion the Persians were promoting for political reasons. These books nominally come from the two centuries before the “restoration” but were obviously anachronistically cast back in time to justify Persian novelties. The priestly schools blamed the troubles of the Am ha Eretz on to their old religious habits—and they laid it on thick—they were abominations!

In Ezekiel, the prophet is transported from Babylon to Jerusalem by God himself to see the abominations that are happening. The Persian reformers composed this to justify Ezra’s alterations to worship in the city of Jerusalem. The abominations are a phallic image (“an image of jealousy that provokes jealousy”), presumably an Asherah; the worship of a variety of images; the worship of Tammuz, the dying and rising god whose consort was Ishtar (Ashtoreth); the worship of the sun that was doubtless an aspect of El, Baal and Yehouah as sky gods. The Persians apparently were not against the vision of the sun being used as an aspect of their transcendental god, Ormuzd, because Mithras was apparently exactly that, but they would not have anything worshipped except for the God of Heaven himself. Mithras transformed himself for the Jews into the archangel Michael, guardian angel of the faithful of Yehouah, a mighty prince of the heavenly hosts but only an angel.

Small clay figurine of an ancient fertility Goddess dated to approximately 7000-7,500 years ago (Source: Haaretz). This figurine was discovered near Gedera in south-central Israel.

Small clay figurine of an ancient fertility Goddess dated to approximately 7000-7,500 years ago (Source: Haaretz). This figurine was discovered near Gedera in south-central Israel.

An Aramaic papyrus from the Jewish military colony at Hermopolis in Egypt speaks of a temple to the Queen of Heaven in the fifth century BC, just when the priests of Nehemiah or Ezra would have been forging the Jeremiah pseudepigraph, on our surmise. We know from the Elephantine papyri that the Jews of Elephantine were still worshipping other gods and goddesses besides Yehouah, including Anath, around 400 BC!

Yehouah’s Spouse

Utterance of Ashyaw the king: Say to Yehallel and to Yaw’asah

and to… I bless you by Yahweh of Samaria and his asherah

At Kuntillet Ajrud in the Negeb 30 miles from Kardesh Barnea, excavation of an eighth century sanctuary by the University of Tel Aviv in 1975-1976 revealed inscriptions, including Hebrew prayers, that have still not been published 30 years later. The text of one prayer was illustrated with two rough figures like the brutish Egyptian god, Bes, and spoke of “Yehouah and his Asherah”. This was a severe kick in the teeth for traditional Jewish and Christian monotheists of the “God’s Plan” variety. Asherah is a Ugaritic goddess, the consort of El. The people of eighth century BC Palestine had this same goddess, and she was considered the consort of Yehouah. Yehouah seemed even closer than ever to Baal or El. The Arabs before the foundation of Islam also had a goddess Asherah, and the Nabataean Arabs, judging by many inscriptions they made in Sinai in the second and third centuries AD, worshipped a god called “Ywh”. The fifth century Jewish colony at Elephantine on the Nile, similarly had Yehouah paired with a goddess Anath-Yehouah.

Bronze figurine of Anat or Anath dated to 1400–1200 BCE, discovered in Syria (Source: Camocon for Public Domain).

In the bible, Asherah is depicted as a cult object apparently a wooden pillar or tree trunk, but translated often as “grove”. Fighting fires and painting over cracks or whatever other metaphor comes to mind—they all apply—biblicists claim that God’s asherah was just a candlestick or altar, or they concede that some evil Jews did allow Yehouah to have a wife and that is why they Jews were always being punished, or anything that sounds plausible as long as it does not mean that Yehouah was not a perpetual batchelor. But as Theodore Lewis points out in the Oxford Companion to the Bible:

The asherah symbol in its origin is not easily divorced from the goddess Asherah.

The archaeological evidence is that the “pre-exilic” Israelites worshipped first and foremost, a goddess whose spouse was titled Baal and sometimes called Yehouah—the causer of being (meaning existence, life). The people saw the goddess as the accessible deity, even if notionally Yehouah or El were superior gods in the hierarchy. In the same way, Christians pray to Jesus or to Mary or even to saints instead of the omniscient god because they clearly do not believe that God is omniscient. And they obviously finish up just as satisfied praying to an old dead bishop as they do to the Almighty God of heaven Himself!

The Persians stopped goddess worship and replaced the old Baal Yehouah with a new god of heaven in the image of Ahuramazda. The constant theme of the Jewish scriptures of apostasy began here, Ezra’s priests portrayed the old religion as a perversion and an abomination of the wishes of the new god, and created an imaginary history of relapsing into religious perversion to justify the change. The prophets were pseudepigraphic propaganda supporting this scheme. Interestingly, later on, after the new god had been accepted, Jews became so protective of the new god that they refused to accept the gods of the Greeks and eventually started the Maccabaean wars. The works written to persuade the Am ha Eretz to adopt the new god were now seen as directed against the Hellenizing Jews who wanted to adopt Greek ways.

Yet, despite this manipulation, the Jews would not give up their attachment to a goddess. It simply had to find new forms, acceptable to those whose only deity was a lonely and invisible Almighty.

One way that is plain in the scriptures, is that the land and people of Yehouah, Israel itself, appeared in place of Asherah or Anath as the betrothed or the wife of God. The goddess remained in the Jewish world view but as a metaphor for the object of the love of Yehouah—his people. This fitted in so well with Persian aims that it is conceivable that they used it as a way of weaning the native Israelites off their attachment to the Goddess, just as Christians permitted Pagan gods to be seen as Christian saints. At any rate it is a strong theme through many of the Persian books of the scriptures.

Depiction dated to 1200-1150 BCE of a fertility goddess (Source: The Fertility Goddess). This was discovered in Ugarit.

Those who refused to abandon the old ways in favor of the new Yehouah were portrayed as a wanton wife, a promiscuous Israel, an unworthy bride or wife. If “His people” abandoned the old ways, then Yehouah would forgive them of their sins and repent of His anger, and approach Israel to unite with her, his erstwhile unfaithful wife, in a grand marriage, to which the faithful would be invited but not the remaining apostates. We have suggested elsewhere that this marriage ceremony was celebrated as a ritual by the Essenes, at least (the wedding at Cana), but whether it is a carry over of some older ceremony in which Baal Yehouah “married” his consort is unclear, though quite likely. The older ceremonies were blatantly sexually promiscuous and the new symbolic ceremony which replaced the previous Bacchic-like revels was doubtless seen as a progression to total decorum.

The old goddess became personified as Zion, the city of Jerusalem representing those who worshiped Yehouah—the Jews or Yehudim, a word apparently related to “yahad” meaning a tightly knit community. Zion was a loving mother or a tender and affectionate daughter to Yehouah—the roles of the goddesses Asherah (mother of Baal) and Anath (daughter of El). She became even more important in the Hellenistic period when she represented the aspirations of the Jews for a kingdom of God—independence from the Greeks.

Cherubim

The reputation of Judaism as an an iconic religion—one which does not permit images—evidently was built after the Persian “restoration”. The making of “any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth (Ex 20:4)” was written in by the priests of Ezra to prevent the people of the Hill Country from reverting to their Asharoth. Yet cherubim decorated the walls of Jewish temples until the end of the temple of Herod in 70 AD. Surely these were “graven images”.

Christians, unassailable in their perpetual ignorance, think cherubim are baby angels like the putti of the medieval illustrators. Well they were indeed winged creatures but they were more like the griffins, winged bulls and winged lions of Assyria than podgy baby angels, though angelic figures were also cherubs. These fabulous creatures were popular all over the ancient Near East for thousands of years, but perhaps reached their artistic zenith under the Assyrians. They were certainly brought by the Persian priests of Ezra from Babylonia, where they decorated thrones, gates and walls. Support for this is the word itself which is not from a Hebrew root. The nearest word for it is found in Akkadian tablets where it stands for an intermediary between humans and god—an winged beast that carries human prayer to god.

Cherubs are first mentioned as having been set to guard the entrance to the Garden of Eden with a flaming sword after the expulsion of humanity (Gen 3:24). In Exodus (25:18-22; 37:7-9), lengthy instructions are giving for the construction of the Ark of the Covenant with its Mercy Seat and decorated curtains. Cherubim were the decorative motif. In 2 Samuel 2:11, God rides on a cherub and in Ezekiel’s vision four cherubim carry the throne of God.

Elsewhere, God sits enthroned on the Ark’s cherubim (2 Sam 6:2; 1 Chron 13:7;Ps 80:1) or sits between them (Ex 25:22; Num 7:89). And in the Psalms, Yehouah “rides on the wings of the wind” (Ps 104:5) or “upon the clouds” (Ps 68:5) or “makes the clouds his chariot” (Ps 104:5). In 2 Samuel 22:11, we read:

And he rode upon a cherub, and did fly: and he was seen upon the wings of the wind.

Psalms 18:10 is equally explicit and emphatic that a cherub stands for the wings of the wind:

And he rode upon a cherub, and did fly: yea, he did fly upon the wings of the wind.

These descriptions explain to us what the cherubim that supported god or his throne were. The Jewish scriptures are describing the common near eastern representation of God, or His Fravashi, used by the Persians and other nations like the Assyrians. The Egyptians also used a similar device—a winged disc that was often shown hovering over a dead person or a religious scene, standing for the soul of the dead or perhaps, more abstractly, for the protective power of god—holiness.

The Egyptians liked to picture Horus between the twin goddesses, Isis and her sister, Nephthys, shown as mirror images of female cherubim, with the winged disc floating above, doubtless representing god as Ra. Equivalent pictures are found in Mesopotamia with two winged gods or goddesses (cherubs) tending a sacred palm tree overlooked by the holy ideogram. This is doubtless the type of scene described as the one on the cover of the Ark of the Covenant. Furthermore, it sounds like the scene repeated several times in 1 Kings as being the general motif of the chambers of the temple:

Goddesses in the form of cherubim with stylized palm tree like the description of those decorating the temple; from Nimrud, Assyria, 900 BCE (Source: CAIS).

And he carved all the walls of the house round about with carved figures of Cherubim and palm trees and open flowers, within and without… The two doors also were of olive tree and he carved upon them carvings of Cherubim and palm trees and open flowers, and overlaid them with gold, and spread gold upon the Cherubim, and upon the palm trees. So also made he for the door of the temple posts of olive tree… And he carved thereon Cherubim and palm trees and open flowers: and covered them with gold fitted upon the carved work. (1 Kings 6:29-35)

Gods in the form of cherubim with stylized palm tree like the description of those decorating the temple; from Nimrud, Assyria, 900 BCE (Source: CAIS).

The description of the visionary temple in Ezekiel matches this (doubtless it was written first) and adds the detail that the cherubs faced alternately just as they do in the Assyrian pictures. Only the Janus-like nature of the heads differs:

And it was made with Cherubim and palm trees, so that a palm tree was between a cherub and a cherub; and every cherub had two faces; So that the face of a man was toward the palm tree on the one side, and the face of a young lion toward the palm tree on the other side: it was made through all the house round about. From the ground unto above the door were Cherubim and palm trees made, and on the wall of the temple… And there were made on them, on the doors of the temple, Cherubim and palm trees, like as were made upon the walls; and there were thick planks upon the face of the porch without. (Ezek 41:18-20;25)

Even the ten wash stands in the temple were set on bases which had a decorative motif of palms, bulls, lions and cherubim.

The two cherubs placed in the Holy of Holies of the temple, however, from their description in the scriptures, seem more like the ideogram of Ahura Mazda:

“And in the most holy house he made two cherubim of image work, and overlaid them with gold. And the wings of the cherubim were twenty cubits long: one wing of the one cherub was five cubits, reaching to the wall of the house: and the other wing was likewise five cubits, reaching to the wing of the other cherub. And one wing of the other cherub was five cubits, reaching to the wall of the house: and the other wing was five cubits also, joining to the wing of the other cherub. The wings of these cherubims spread themselves forth twenty cubits: and they stood on their feet, and their faces were inward” (2 Chronicles 3:10-13; see also 1 Kings 6:23-28).

Is this how the cherubim in the temple Devir at Jerusalem looked? (Source: CAIS).

The cherubim were miraculous because they faced each other only when Yehouah favoured Israel but the faced away from each other when Israel had earned God’s ill will. But why were there two when there is only one god? In Rabbinic tradtion, there are two cherubim to stand for each of God’s holy names, Yehouah and Elohim, and, though this is much later than the origin of these images with the Persians, it could be true. There seem to have been two factions, each rooting for their preferred god, further proof that the religion of the Israelites before the arrival of the Persians was polytheistic.

Now Judaeo-Christian tradition has always been that the Holy of Holies of the temple was empty, once the Ark of the Covenant had disappeared from it, despite the descriptions of the cherubim in the scriptures. In fact, there must always have been fires burning in there if only for the burning of incense, but fires were holy themselves in Persian tradition and considered to be good spirits that took the prayers of the faithful up to god along with the sweet incense. Rabbi Hanina in the first century AD reports that there was a fire on the altar, and this was obviously not the altar for burnt offerings which stood outside the Holy Place, and necessarily had a fire. This altar is distinguished in Exodus 38:1 from the altar of incense of Exodus 37:25. The Holy of Holies and the Holy Place were a single room, separated only by a veil.

The Ark was meant to rest beneath the touching outstretched wings of the cherubs, but the loss of the Ark would not have stopped the temple authorities from maintaining the cherubs. Only the Ark was unique and irreplaceable. These cherubs are both shown as masculine in appearance, just as Yehouah is always taken to be masculine in every respect. A later reason for there being two images was that one of the cherubim in the Holy of Holies of the second temple was female—the goddess had not really disappeared at all!

The basis for this belief is also the Talmud, which tells us that the two cherubs in the Devir of the temple were a copulating couple! Well, the Talmud actually says they were “entwined” like a man and his wife. This explicit sculpture was displayed to the pilgrims on each of the three major festivals—Passover, Pentecost and Tabernacles.

Table prepared for a Passover Seder (Source: DataFox for Public Domain).

Both Philo of Alexandria and Josephus must have known what was in the Devir, but both are cagey or contradictory. Philo says that the High Priest is so blinded by the incense smoke when he enters that even he cannot see what is in there, and Josephus says that nothing is there, then that what is there is quite respectable, and lastly he admits that there are some items of sacred paraphernalia in there.

Both must have known, because Josephus had served as a priest and Philo had visited Jerusalem as a pilgrim. Rabbi Quetina, according to Raphael Patai, says that the priests would role up the veil separating off the Holy Place when pilgrims arrived to show them the “cherubim that were intertwined with one another”, and declare:

Behold! Your love before God is like the love of male and female.

The pilgrims would then indulge in orgiastic behaviour, as they had done under the old religion, as the incident of the golden calves proves:

And they rose up early on the morrow, and offered burnt offerings and brought peace offerings, and the people sat down to eat and to drink, and rose up to play. (Ex 32:6)

No prizes are offered here for the real meaning of the mis-translation “play”. The same Hebrew word is mistranslated differently when the Philistine king, who thinks Rebekah is Isaac’s sister, sees them through his window (Gen 26:8):

Abimelech king of the Philistines looked out at a window, and saw, and, behold, Isaac was sporting with Rebekah his wife.

Yes, the word “l’zaheq” means having nooky. The Jews had been subject to the same religious influences as everyone else in the ancient Near East. Their original religion was a fertility religion based on the cycle of the seasons. If these people wanted the rains to come and the land to be fertile, what reason could they have had for not showing the gods precisely what they required? The sexual act was a sacred act of the cycle of living, and the hierophants revealed the sacred object that stimulated the act. It would have been impossible for them to have remained chaste when they wanted the land to be fertile.

Doubtless the Persian schools could not have tolerated such behavior, which suggests it only resumed after Alexander’s conquest. The priests were, of course, interested in multiplying the seed of Abraham, who were their bread and butter, and the Greek regime was sexually liberal, so that the new generation of Hellenized priests had good reason for promoting occasional orgies, even if the Jews had become otherwise prudish under Zoroastrian influence. Effectively they were re-admitting the old religion of Baal and the Queen of Heaven, but under the guise of a mystery religion in which the cult objects were revealed periodically only to the faithful. Naturally, traditional Jews—those now committed to the religion introduced by the Persians—would have seen all of this as abominable. They became the Hasidim who split into Pharisees and Essenes.

Elsewhere, the Talmud describes the discovery of the entwined cherubs by foreigners violating the temple’s sanctity:

They entered the Holy of Holies and found there the two cherubim, and they took them and put them in a cage and went around with them in the streets of Jerusalem and said: “You used to say that this nation was not serving idols. Now you see what we found and what they were worshipping”.

These violators are supposed to have been Ammonites and Moabites, but the only historical event that it could correspond to before the restoration was the capture and robbing of the temple by Nebuchadnezzar, and the Persian “restorers” would have included evidence of such an abomination in the salutary works they wrote that now constitute the prophetic books of scripture. The event therefore took place in the Greek period when it became normal for Jews to refer to the Greeks by the scriptural names of their gentile enemies. The Ammonites and Moabites must therefore have been really Greeks and the desecration and parading of the sculptures in cages must have happened before the Maccabaean war. The desecration of Antiochus Epiphanes in 170 BC seems the likely occasion.

A traditional portrayal of Ezekiel’s vision (Biblical book of Ezekiel, chapter 1) of the cherubim and chariot (Source: Public Domain). This is actually a 1670 illustration based on Matthaeus (Matthäus) Merian’s (1593-1650) earlier version.

A traditional portrayal of Ezekiel’s vision (Biblical book of Ezekiel, chapter 1) of the cherubim and chariot (Source: Public Domain). This is actually a 1670 illustration based on Matthaeus (Matthäus) Merian’s (1593-1650) earlier version.

The old cherubim in the shape of the ideogram of Ormuzd must have been replaced by the sensuous statue of copulating cherubs after the defeat of the Persians by the Greeks. Patai suggests that the change was effected by Ptolemy Philadelphus who made several expensive gifts to the Jewish temple and began the translation of the Torah into Greek. Perhaps more likely is his son Ptolemy III Euergetes, who was a noted Judaeophile and even worshipped at the Jerusalem temple, according to Josephus. His son, Ptolemy Philopator, wanted also to worship in the temple but was prevented from doing so and planned to massacre Jews in revenge. He regarded the Jews as being devotees of Dionysos and therefore had Jewish slaves tattooed with a vine leaf.

When the Maccabees rededicated the temple in 165 BC, did they restore the statuary destroyed by Antiochus Epiphanes? It seems they did, because the cageyness of Philo and Josephus suggest it, and the fact that the Hasids fell out with the Hasmonaeans has the same implications. The excuse given by apologists is that some Hasids objected to the Maccabees taking the priesthood, reserved for the Zadokites, but the real reason will be that they had returned the institutions to those of the Greek inclined sect of the Sadducees, who claimed they were the heirs of the Zadokites, instead of back to the religion introduced by the Persians.

Nevertheless, for many Jews the attraction of the goddess remained and she had had a metaphorical existence as the bride of God, Israel. The explicit statue must have seemed to many a graphic illustration of the intimacy of Yehouah and His people, and therefore did not seem in the least improper. And a goddess equal to Yehouah had reappeared as the female cherub in the statue. It took the growing strength of the Persian parties, the Pharisees and the Essenes to pressurize the priesthood into segregating men and women and preventing them from indulging in sexual flippery when the mysteries were revealed.

Women, who had previously had a temple court of their own giving direct sight of the revealed cherubs, were relegated to second class citizens in galleries having no view of it. The goddess was to fade again into metaphor and the poetic constructions of the Shekinah, the Wisdom of God and the Holy Ghost before the Christians even masculinized even that.