The prestigious Spanish Military History Journal, HRM Ediciones of Historia Rei Militaris published its interview with Kaveh Farrokh on February 12, 2019: Entrevista a Kaveh Farrokh

The interview with Kaveh Farrokh was conducted by Spanish historian Dr. Javier Sánchez-Gracia (seated) during the book signing of his recent text “Imperios de las Arenas: Roma y Persia Frente a Frente” (Empires at the Sand: Rome and Persia Face to Face) during the “Feria del Libro de Zaragoza” book fair on April 23, 2017 in Zaragoza, Spain. Standing next to Dr. Sánchez-Gracia is his friend and colleague Dr. Manuel Ferrando, also an accomplished historian from the University of Zaragoza, Spain. Dr. Sánchez-Gracia is himself an accomplished specialist of Greco-Roman relations with the pre-Islamic Iranian empires of the Achaemenids, Parthians and Sassanians.

The full transcript of the interview (in English) is available below as the final version in Spanish had to be significantly edited (text and images) in order to accommodate HRM Ediciones‘ editorial requirements.

================================================================================

[1] Dear Kaveh, although you live in Canada, you come from an Iranian family, but your ancestry is also from the Caucasus. How do you get to live in Vancouver? How do you see the current situation of Iran?I am born in Greece and as my father (Fereydoun Farrokh) was a career diplomat during the previous Pahlavi establishment.

Above at left is Kaveh’s late father in 1962, Fereydoun Farrokh (1926-2019), the Iranian chargé d’affaires in Greece meeting with Evangelos Averoff (at right) the Greek Foreign Minister (Source: this photo has been published by Dr. Evangelos Venetis in his book “Greeks in Modern Iran” in 2014). The Minister is entrusting a cheque on behalf of the Greek government to Fereydoun Farrokh to send to Iran to financially assist Iranian earthquake victims at the time. Kaveh was born in Greece in 1962, during his father’s diplomatic mission to Greece.

I pretty much grew up in Europe. My schooling was in American and International schools, and I still have fond memories of the Berlin American High School (BAHS) where I spent most of my high school years.

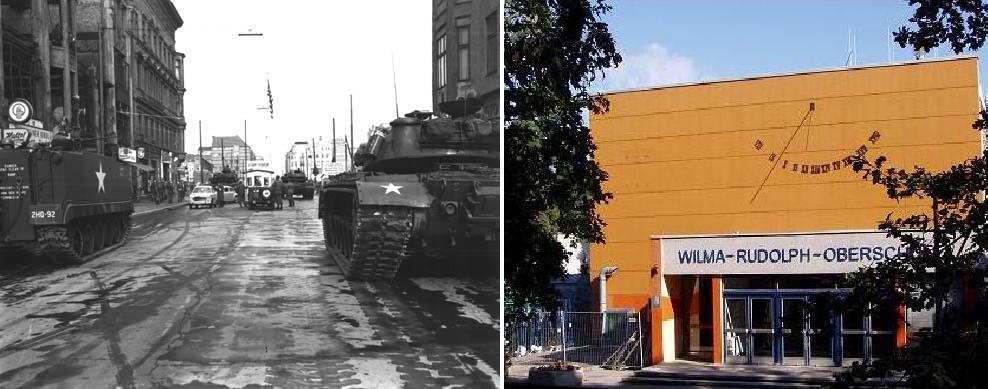

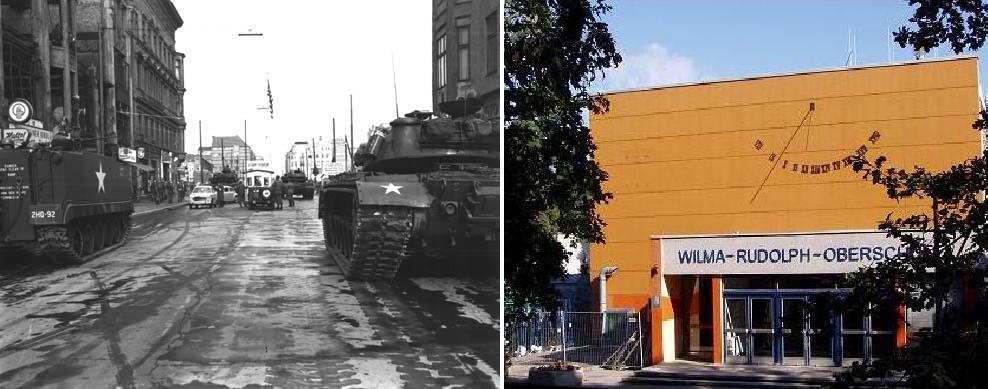

Hot spot of the Cold War – Berlin in the 1960s and 1970s. LEFT: Checkpoint Charlie in the 1960s at the height of the Cold War. Above is a major military standoff between US M-48 tanks (note US M-113 armored personnel carrier at left) and Soviet forces at Checkpoint Charlie which was along the Berlin Wall which separated East from West Berlin (Checkpoint Charlie was on the Western side). RIGHT: Berlin American High School (B.A.H.S.) now known as the Wilma-Rudolph-Oberschule. B.A.H.S was permanently closed in 1994 during the withdrawal of US forces from Berlin following the end of the Cold War. Kaveh crossed the Berlin Wall from East to West Berlin on a daily basis in the 1970s just to get to school (B.A.H.S.).

I only lived a few years in Iran, after my father’s final mission as ambassador to East Germany in 1977. Prior to this my father my father had had a number of other missions to various European countries, including West Germany.

Fereydoun Farrokh and Mahavash Sara Pirbastami (mother of Kaveh Farrokh) welcome the Chinese ambassador in a reception held at the Iranian embassy in Köln (Cologne), West Germany in circa 1966 or 1967.

This is when I spent the most time in Iran in 1977-1978 when the revolution broke out. My family and I immigrated to France in 1979 and I subsequently left for my university studies to England and the US. We then immigrated to Canada in February 1983 where beautiful Vancouver has been our home ever since.

Kaveh Farrokh’s grandfather, Senator Mehdi Farrokh (top row at right) during his tenure in Rezaieh (modern Urumieh) in Azarbaijan province in the 1930s. His wife, Ezzat Saltaneh Tabatabai-Diba (left) is of the long-standing Diba family of northwest Iran. Ezzat Saltaneh was the daughter of Nasrollah (Haj Nasser Saltaneh) Tabatabai-Diba. Mehdi and Ezzat’s daughters in the middle row are Victoria (left) and Parvin-dokht (right) and at the front row stands their son Fereydoun Farrokh.

As per the current political situation in Iran, my perspective is more guided by my focus as a historian and researcher of ancient (pre-Islamic) Iran. As you may know the current establishment ruling in Tehran is pan-Islamist in its outlook and is in general less interested in ancient Iran. Let us look at Shirin Hunter’s recent analysis published in LobeLog (March 7, 2017):

“The current government’s…priorities… emphasize vague and unattainable Islamist goals …”

While true that the Rouhani administration is considered as more moderate than other factions of the current establishment, the pan-Islamist faction remains very entrenched in the system, with a particular bias against pre-Islamic Iran or Persia. Take for example this statement by Mr. Ali Larejani (who has served as the Chairman of the Iranian parliament), in a speech he gave to Tehran’s prestigious Sharif University, May 2003:

“Sadly, much lies are told today of Iranians before Islam, the extent of their culture and civilization, and the burning of their libraries during the Muslim invasion…Before Islam Iranians were an illiterate, uncivilized and basically barbaric people who desired to remain as such.”

While too numerous to list here other examples of such sentiments include Grand Ayatollah Safi Golpayegani in Iran composing anti-Persian Poetry (in the Persian language) or the academic Dr. Sadegh Zibakalam’s declaration that:

“I would not give/exchange a single hair of an Arab … for hundreds of Cyrus’, Darius’, Xerxes’, Iran’s past [history]…and Persepolis!”

Note that Zibakalam is considered as a reformer and a neo-liberal. Another example is Hassan Rahimpour Azqadi, a major theoretician, academic and member of Iran’s Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution, stated in the Payam-e Nour University of Mashad on March 11, 2014 (just days before the ancient Nowruz Iranian new year) that:

“The Aryans drank the sewage of cows as a sacred drink…now that you wish to be proud of being Aryan, go and be Aryan”.

As noted already, such sentiments are also shared by reformist faction of the Iranian establishment. Mir Hossein Moussavi, the reformist candidate who ran against president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad during the 2009 Iranian Presidential elections, had stated in 1982 that the pre-Islamic history of Iran before 1979 had been fabricated during the Pahlavi era and two years after that claimed that the use of ancient (pre-Islamic) Achaemenid architecture as inspiration for contemporary architecture was a “disaster”.

While little noticed in Europe or North America, a select few Western media outlets have been diligently reporting these Persophobic policies, or more specifically bias against ancient pre-Islamic Iran. Recent University of New England graduate Dr. Sheda Vasseghi has been writing diligently against this historical revisionism by the pan-Islamists. In one of her articles “Rewriting the History of Iran” in the World Tribune (September 15, 2009) Dr Vasseghi avers:

“…any degree of bias observed in foreign sources about ancient Persians is nothing compared to the negativity, falsehood, and insufficient information provided by the current Iranian establishment to Iranian children… The overall tone is negativity towards … the nation’s culture and history … ancient Persians are described as greedy, unjust, chaotic, and selfish… There is no mention of the ancient Iranian prophet, Zoroaster, who is credited with being the first monotheist… suggests that Cyrus’ motivation for conquest was to become wealthy. Nothing is mentioned of Cyrus’ famous bill of rights cylinder and his decree in freeing the Jewish captives from Babylonia while taking on the financial responsibility to rebuild their temple… [pan-Islamists] are … systematically destroying a nation’s understanding of its past …”

Just days later Dr. Vasseghi’s report was corroborated by the BBC Persian-language outlet which made an extensive report on September 22, 2009 entitled “The elimination of the history of pre-Islamic monarchs of Persia in Iran’s History books ”

. Anti Indo-European sentiments have also been officially expressed (most recently in September 2016 on Radio Farda TV) by certain (possibly politically-oriented?) academics in Iranian Studies venues. Readers however must be reminded that there are many Iranian Studies professors outside of Iran and also inside Iran who oppose the historical revisionism of the authorities. Nevertheless, the Vasseghi and BBC articles have accurately exposed the process of historical revisionism that is taking place by the pan-Islamist factions.It is hoped that, that the current (and upcoming) political process will reverse the nearly four-decade policy of de-Iranization or de-Persianization. All countries and peoples deserve to have a balanced view of their past and legacy and in Iran’s case this involves appreciating her ancient Indo-European past alongside her more recent (1400 year) Islamic legacy. In addition the history of ancient Iran also belongs to that of ancient Europe. The common assumption is that Europe is mainly derived from a Greco-Roman and Judeo-Christian tradition but in fact there is a strong Indo-European and Zoroastrian element that has influenced not just Europe per se, but also the same Greco-Roman and Judeo-Christian elements.

=============

[2] Our image of the ancient Persians comes from Greco-Latin authors, How would you describe those Persians, who were rivals of Alexander the Great or Trajan?

Much of our image today of “the Other” is based on the selective interpretation of the Classical sources made by mainly English and French and other northwest European scholars, especially from the 19th century onwards. This is not to say that hostile references do not exist in the ancient sources – of course they did, given the hegemonic conflicts that occurred between the two realms. The ancient Persians themselves however did not necessarily view the Greco-Roman civilization strictly as rivals per se, especially if we refer to the Sassanian era. Let us look for example to Apharban, the Persian ambassador representing Sassanian king Narses (r. 293-302 CE) during negotiations with Galerius, a Roman general Galerius after his victory over Sassanian forces in 291-293 CE – Apharban declared this to his Roman hosts:

“It is clear to all mankind that the Roman and Persian empires are like two lights, and like (two) eyes, the brilliance of one should make the other more beautiful and not continuously rage for their mutual destruction.”

These sentiments continued well into the late Sassanian era, before the fall of pre-Islamic Persia to the Arabs in the 7th century CE. In his letter to Romano-Byzantine emperor Maurice, Sassanian king Khosrow II wrote the following:

“God effected that the whole world should be illumined from the very beginning by two eyes, namely by the most powerful kingdom of the Romans and by the most prudent scepter of the Persian State. For by these greatest powers the disobedient and bellicose tribes are winnowed and man’s course is continually regulated and guided”

Apharban and Khosrow II were simply stating the Persian perspective that Rome and Persia were seen as the two major civilizations of antiquity in the west, with India and China predominating in the orient. Neither Rome nor ancient (Achaemenid, Parthian, Sassanian) Persia were “racial” empires – instead they were multifaceted civilizations with complex interrelationships in the arts, architecture, technology, engineering, theology, governance, commerce and militaria. The ancient Iranians also considered themselves as the guardians of knowledge and learning. Let us take the case of the Neo-Platonic Greek scholars who were expelled from Athens in 529 CE by Emperor Justinian (482-565 CE). They were welcomed into Persia’s Gundeshapur by Khosrow I Anushirvan (531-579 CE) where they continued their research in the Mathematics, Astronomy and Medicine. Let us get a glimpse into the Sassanian philosophy of learning in the Middle-Persian (Pahlavi) text, the Karnamag:

“We have made inquiries about the rules of the inhabitants of the Roman Empire and the Indian states. We have never rejected anybody because of their different religion or origin…it is a fact that to have knowledge of the truth and of sciences and to study them is the highest thing… He who does not learn is not wise”.

As indicated by the Karnamag, the Sassanians evinced a similar interest in Indian philosophy, medicine and sciences.

A detail of the painting “School of Athens” by Raphael 1509 CE (Source: Zoroastrian Astrology Blogspot). Raphael has provided his artistic impression of Zoroaster (with beard-holding a celestial sphere) conversing with Ptolemy (c. 90-168 CE) (with his back to viewer) and holding a sphere of the earth. Note that contrary to Samuel Huntington’s “Clash of Civilizations” paradigm, the “East” represented by Zoroaster, is in dialogue with the “West”, represented by Ptolemy. Prior to the rise of Eurocentricism in the 19th century (especially after the 1850s), ancient Persia was viewed positively by the Europeans. For more see Ken R. Vincent: Zoroaster-the First Universalist …

Notice that these citations of history are rarely mentioned in academia or the media. Instead much of (but not all as there are notable exceptions) Western scholarship in Classical Studies continues to promote a distinctly Eurocentric approach, especially in trying to present Greco-Roman and Persian civilizations as completely opposite, hostile, unrelated and even isolated from one another.

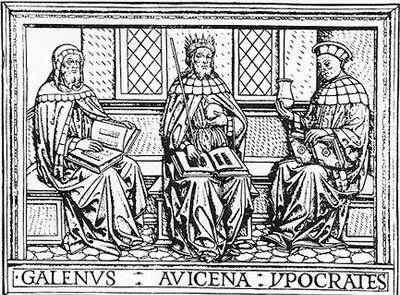

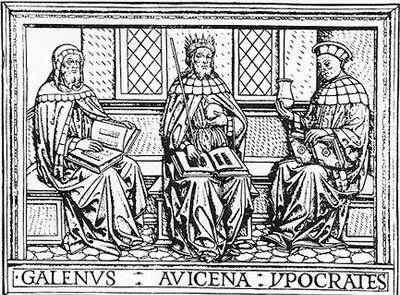

A medieval portrait of the sages of medicine: Galen (left), the Iranian Avicenna (center) and Hippocrates (right). (980 -1037). Avicenna (or Abu Ali Sina) was born in Afshana, near (Bukhara), the ancient capital of the Iranian Samanid dynasty. The Arab Scholar Al-Qitfi has noted that “They (the Persians) made rapid progress in science, developing new methods in the treatment of disease along pharmacological lines so that their therapy was judged superior to that of the Greeks and Hindus” (as cited in Elgood, 1953, p.311, Legacy of Persia (edited by A.J. Arberry), Clarendon Press).

Western writers and Classicists often emphasize the antagonistic aspect of East-West relations, especially with respect to the wars of the Greeks and their Roman successors against pre-Islamic Persia. The main aim of this is to portray history as a endless series of wars between the “West” (meaning the Greco-Roman world) which is portrayed as democratic and civilized versus the undemocratic, irrational, barbaric and un-democratic “East” (i.e. ancient pre-Islamic Persia).

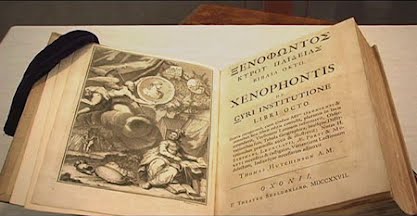

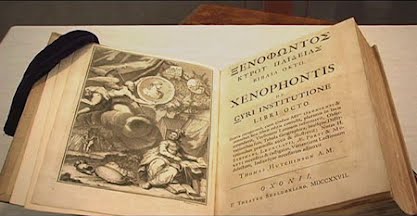

But in reality there are also positive praises of ancient Iran by Greek writers, such as Xenophon’s Cyropaedia in reference to his writings with respect to Cyrus the Great. Drijvers for example highlights the fact that Roman and Sassanian Persian emperors’ recognized each other as rulers of equal rank and respect who often sought to establish friendly relations and communications. Eurocentric historians however not only choose to ignore this side of history, but continue to cherry-pick information to present their own biased views. Recall the late Samuel Huntington (1927-2008) who proposed that there is a “Clash of Civilizations” due to the “fact” that the western world has been democratic over millennia in contrast to non-Western world, which is presented in very simplistic terms.

Is there really a “Clash of Civilizations”? One of the lecture slides from Kaveh Farrokh’s Fall 2014 course at the University of British Columbia Continuing Studies Division “The Silk Route: Origins and History [UP 829]”. The slide above – Left: Reconstruction of a European Renaissance Lute; Right: Moor and European play their respective Oud-Lutes in harmony (from the Cantingas of Alfonso el Sabio, 1200s CE) – note that Oud-Lutes were derived from the Iranian Barbat and Tanbur originating in pre-Islamic Persia.

Note also how ancient Iran and the modern-day Islamic world are (incorrectly) lumped into one entity. The late Edward Said (1935-2003) had argued against such paradigms (which he termed as “Orientalism”). Said noted that such Orientalism only serves to reinforce simplistic, Eurocentric and racist views of history and current events. Indeed Binsbergen has warned us of the fact that much (but not all of course) of Western scholarship continues to be challenged by:

“…the Eurocentric denial – as from the eighteenth century CE – of intercontinental contributions to Western civilization” and that “…Eurocentricism is the most important intellectual challenge of our time”.

The importance of Binsbergen’s observation cannot be overstated – especially in these times of strife, conflict and animosity. The path to healing in this age is through honest and balanced history writing. It is time that humanity as a whole realizes that our histories are shared, and when we share the whole truth, we finally arrive at an image of each other free of errors, hostility and bias.

=============

[3] In Spain there are those who affirm that if it had not been for Leonidas and his Spartans, today we would speak Persian. What, in fact, was the purpose of Xerxes invading Greece?

I would humbly (as before) diverge from this interpretation. First, there already were Iranian speakers in Europe, with Iranian languages being of the same linguistic family as other Indo-European languages. The Scythians were already well-established in Eastern Europe, notably modern-day Ukraine and parts of Bulgaria and Romania with Scythian artifacts having been found in modern-day Germany.

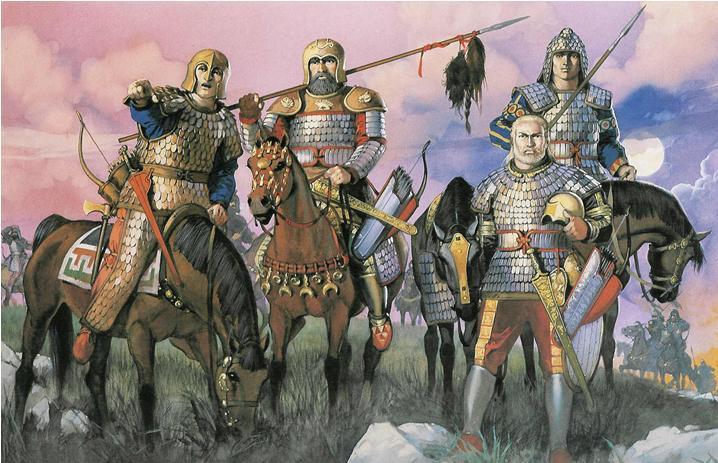

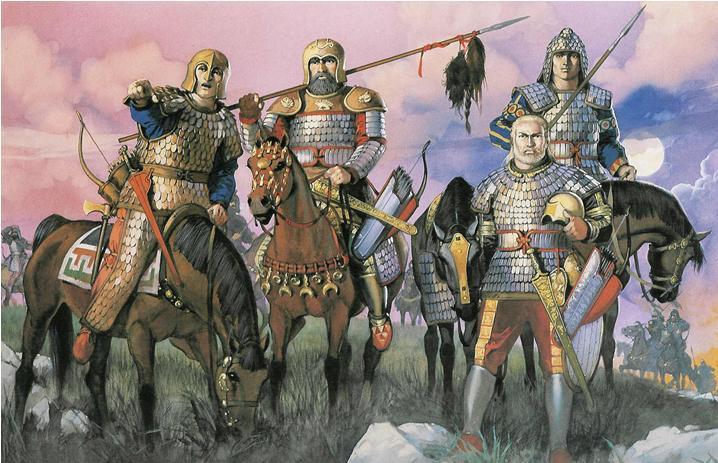

Scythians of the ancient Ukraine. Scholars are virtually unanimous that the Scythians were an Iranian people related to the Medes and Persians of ancient Iran or Persia (Painting by Angus McBride).

Iranian peoples such as the Sarmatians, Alans and countless others continued to migrate into Europe after the fall of the Achaemenids during the reign of the Parthians and early Sassanians reaching as far as modern-day France.

Roman tombstone from Chester (housed at Grosvenor Museum, item #: 8394907246), UK depicting Sarmatian horseman attired like other kindred Iranian peoples such as the Parthians and Sassanians (Source: Carole Raddato, uploaded by Marcus Cyron in Public Domain).

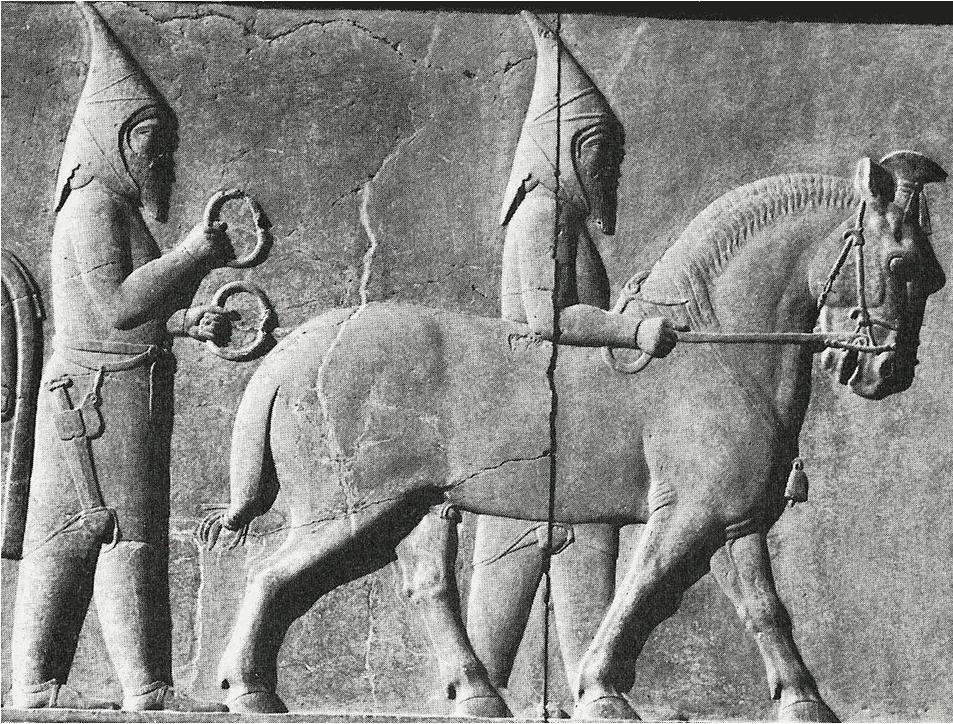

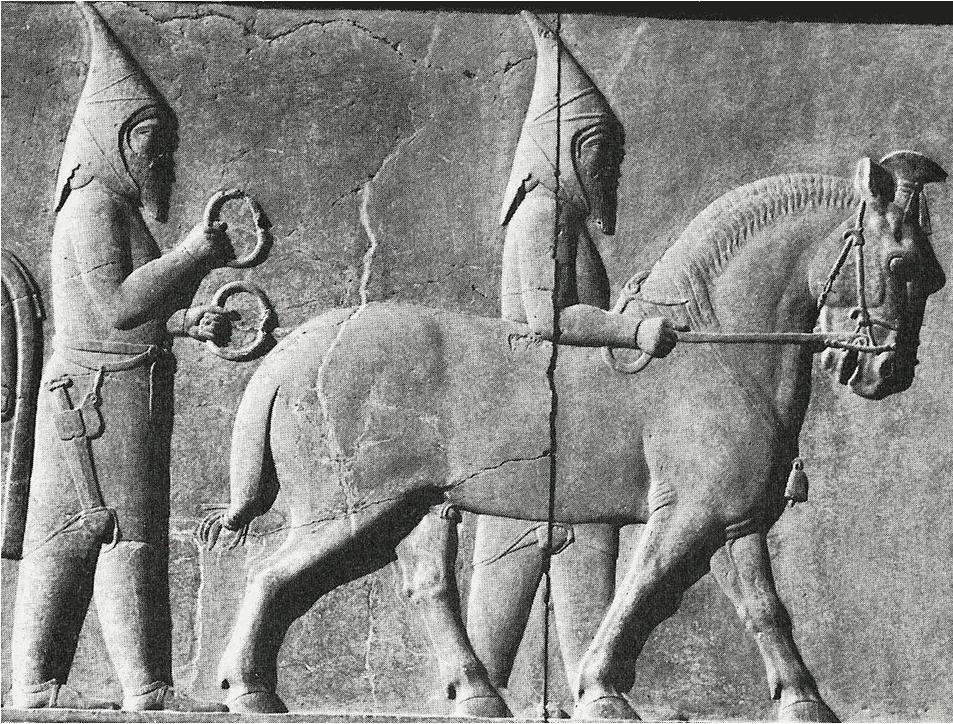

Saka Tigra-khauda (Old Persian: pointed-hat Saka/Scythians) as depicted in the ancient Achaemenid city-palace of Persepolis. It was northern Iranian peoples such as the Sakas (Scythians) and their successors, the Sarmatians and Alans, who were to be the cultural link between Iran and ancient Europe (Picture used in Kaveh Farrokh’s lectures at the University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division and Stanford University’s WAIS 2006 Critical World Problems Conference Presentations on July 30-31, 2006).

Iranian-speaking Alans for example arrived alongside the Goths into Spain (hence the legacy of Catalan = Goth-Alan). Alan contingents for example were dispatched to Britain by Emperor Marcus Aurelius.

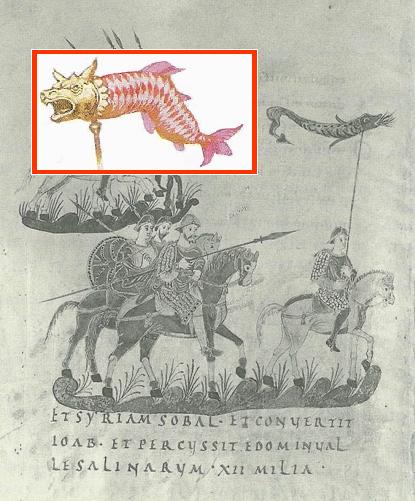

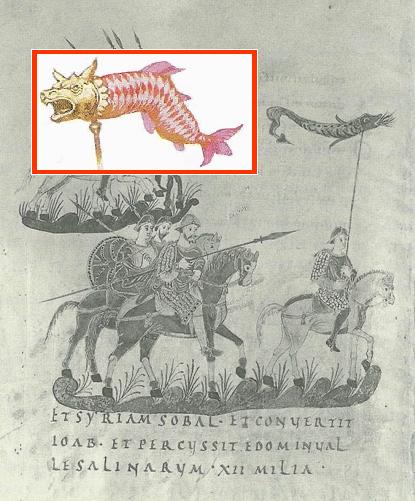

A depiction of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae and Sir Thomas Mallory’s Le Morte d”Arthur. Note the windsock carried by the horseman (Farrokh, page 171, Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War-Персы: Армия великих царей-سایههای صحرا) – this item was bought from the wider Iranian realm (Persia, Sarmatians, etc.) into Europe by the Iranian-speaking Alans. The inset depicts a reconstruction of a 3rd century CE Partho-Sassanian banner by Peter Wilcox (1986).

The close ties of Iranian peoples with Europe was acknowledged until relatively recently as noted by Noah Webster who clearly stated:

“the original seat of the German and English nations was Persia” (p. ix), and “[t]he ancestors of the Germans and English migrated from Persia” (p. 4).

This was in reference to the common origins of Europeans and ancient Iranians. There are numerous such references too long to list here so let us look at another two examples. Professor Christopher I. Beckwith (Professor of Central Eurasian Studies at Indiana University) for example has noted that:

“… the early Germanic peoples, including the ancestors of the Franks, belonged to the Central Eurasian Culture complex which they had maintained since Proto-Indo-European times, just as the Alans and other Central Asian Iranians had done. This signifies in turn that ancient Germania was culturally a part of Central Eurasia and had been so ever since the Germanic migration there more than a millennium earlier” (2009, pp. 80-81)

But it is not just Germanic peoples – we need to look at the Indo-European family with all its members: Europeans, Indians and Iranians. Beckwith further notes to us that:

“The dynamic, restless Proto-Indo-Europeans whose culture was born there [Central Asia] migrated across and “discovered” the Old World, mixing with the local peoples and founding the Classical civilizations of the Greeks and Romans, Iranians, Indians, and Chinese…Central Eurasians – not the Egyptians, Sumerians, and so on– are our ancestors. Central Eurasia is our homeland, the place where our civilization started” (2009, p.319).

Yet today many Europeans remain fixated with exploring Egypt, Sumeria, Babylon and even ancient Tibet as their possible origins, when in fact their Indo-European origins were acknowledged until very recent times.

Such references have been virtually deleted in modern history texts and academia, for many reasons, including political and economic factors. We are often unaware of such facts today, and one reason for this is how our minds are shaped by terminology such as “Middle East”, “Muslim world”, etc. to in order to view and interpret peoples, regions and events in certain ways, which are not necessarily accurate.

A Russian photograph of Ossetian women of the northern Caucasus working with textiles in the late 19th century CE. Ossetians are the descendants of the Iranian speaking Alans who migrated to Eastern Europe, notably former Yugoslavia, and modern-day Rumania and Hungary (where their legacy remains in the Jasz region).

Put simply, Iranians have been integral to the history and development of Europe; the Persian Empire was part of a larger civilizational complex known commonly L’Iran Exterior or Greater Iran.

The celebration of “Surva” in modern-day Bulgaria. Local lore traces this festival to the Iranian God Zurvan. This folklore system appears to be linked to the Bogomil movement. Interestingly, much of the Surva theology bears parallels with elements of Zurvanism and Zoroastrianism (Picture Source: Surva.org).

As per the notion that if the Achaemenids had prevailed, then all under their rule would speak Persian is inaccurate when we examine the nature of the empire itself.

The Persian Achaemenid Empire was in fact a multilingual, multicultural and multireligious state with local languages and traditions being actively encouraged. Darius’ inscription at Behistun is written not just in Old Persian but also in Babylonian, Elamite and Akkadian – and this is INSIDE modern-day Iran.

Thomas Jefferson’s copy of the Cyropaedia (Picture Source: Angelina Perri Birney). Like many of the founding fathers and those who wrote the US Constitution, President Jefferson regularly consulted the Cyropedia – an encyclopedia written by the ancient Greeks about Cyrus the Great. The two personal copies of Thomas Jefferson’s Cyropaedia are in the US Library of Congress in Washington DC. Thomas Jefferson’s initials “TJ” are seen clearly engraved at the bottom of each page.

There was no policy of forced conversions to Zoroastrianism or citizens being forced to abandon their cultures and customs to speak Persian. Let us see for example the observations of the late Professor Berthold Laufer who noted:

“The Iranians were the great mediators between the West and the East, conveying the heritage of Hellenistic ideas to central and eastern Asia and transmitting valuable plants and goods of China to the Mediterranean area. Their activity is of world-historical significance … ” (page185, Publications of the Field Museum of Natural History, Anthropological Series, Volume 15, No. 3, 1919).

Contrary to what we hear on the mainstream press and increasingly in select areas of academia, Iranians supported and mediated the Hellenic heritage. It is also interesting that there is European scholarship that acknowledges the link between the ancient Iranians and Europeans.

Much of what we have seen, especially after 1979 has been a more “modern” view which plays into “othering” the Iranians to lead to a somewhat simplistic and black-white view of history, one that paints the pictures of “Good” versus “Evil” and “Us” versus “Them”. This is neither scientific not historical and turns people away from the entire picture of what really happened in antiquity.

Now let us focus our attention to the invasion of Greece by Xerxes. Perhaps the best summary of events was provided in my lecture “The Other Side of 300” at The Pharos CanadianHellenic Cultural Society in Vancouver, Canada on February 25, 2008. To put it simply, the reasons for the Greco-Persian wars were as much economic as they were political. Broadly speaking there were five reasons summarized below:

1) The sack of Sardis by the mainland Greeks: On the eve of his invasion, Xerxes declared that he wanted to obtain vengeance for the massacre and burning of Sardis inside the Achaemenid Empire by the mainland Greeks during the reign of Darius the Great (Xerxes’ father). Notably the temple of Goddess Cybele had also been burnt by the Greeks, which was the reason Xerxes set fire to the temples of the Greeks as well as Athens during his invasion of 480 BCE. Xerxes was essentially attempting to settle the “unfinished business” of his father Darius, who had failed at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE and died shortly thereafter.

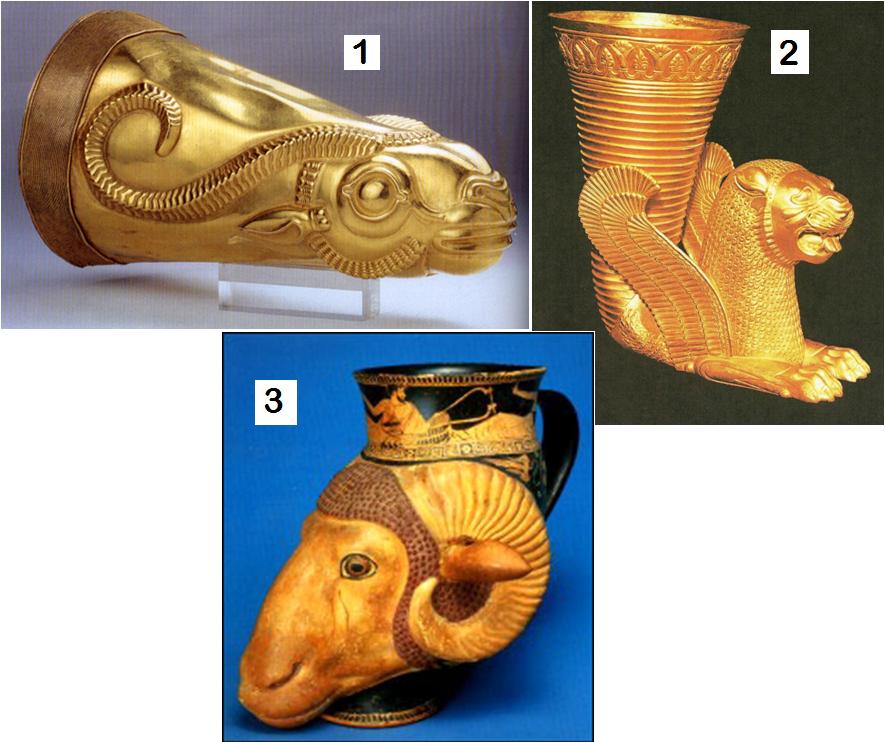

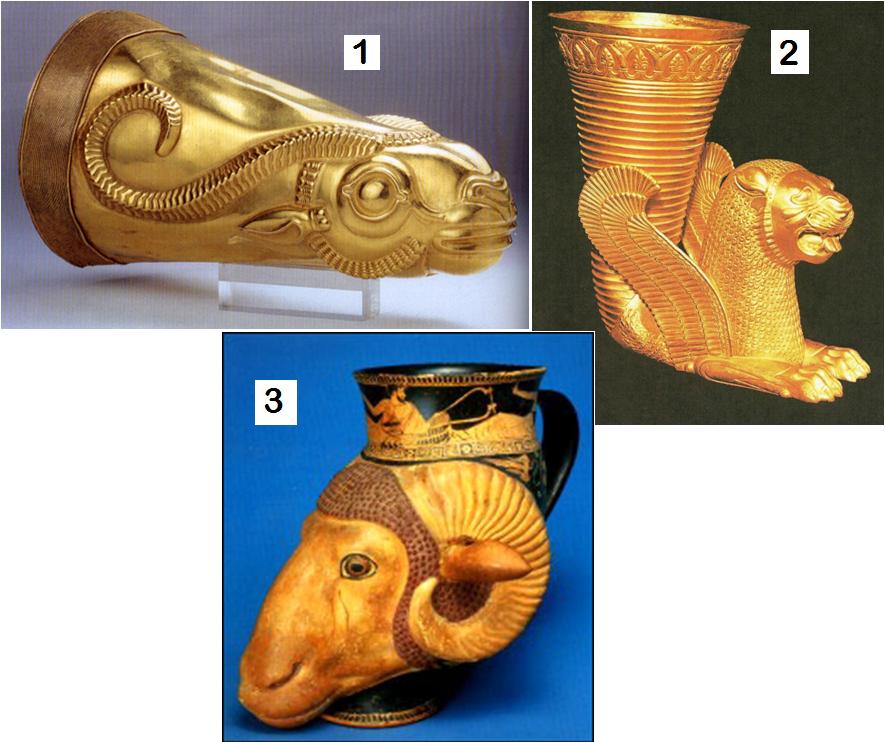

[1-2] Persian Rhythons – many of these were captured after the defeat of Mardonius at Plataea (479 BC) (Herodotus, 9.80)and [3] an Athenian rhyton (Museo di archeologia ligure, Genova) (Pictures 1-2 used in Kaveh Farrokh’’s lectures at the University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division and Stanford University’s WAIS 2006 Critical World Problems Conference Presentations on July 30-31, 2006; Picture 3 originally posted in Iran Chamber Society).

2) Fear of future Greek attacks: Xerxes and the Achaemenid government were greatly concerned that the Greeks would launch more destructive raids on the Achaemenid Empire as they had done already at Sardis.

3) The need to assert imperial (Achaemenid) authority: In Xerxes’ view the mainland Greeks had defied the authority of the king with their invasion of Asia Minor and especially their destruction of Sardis. Failure by the empire to take successful action against Greece would undermine the authority and prestige of the imperial throne and empire.

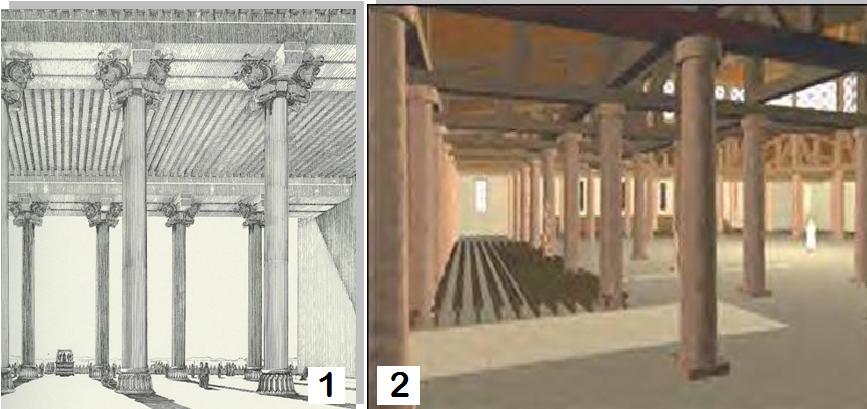

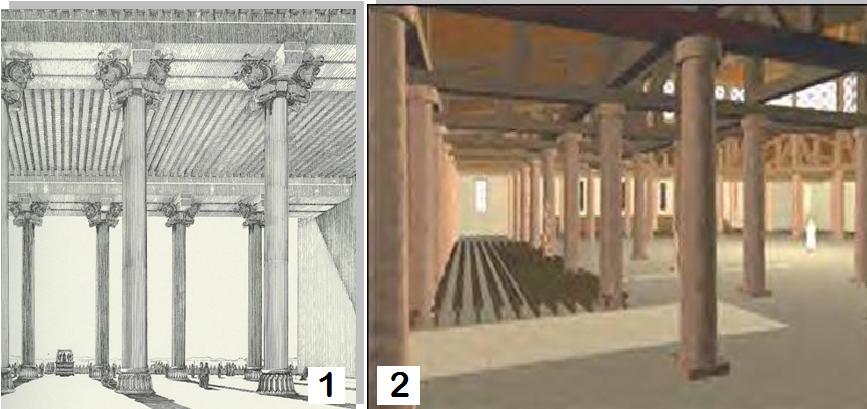

[1] Achaemenid Hall of 100 at Persepolis and with dimensions bearing 68,50 x 68,50 meters – 10 x 10 columns [2] Pericles’ Odeon with dimensions bearing 68,50 x 62,40 meters – 9 x 10 columns (Pictures 1-2 originally posted in Iran Chamber Society).

4) Invitation by anti-Athenian Greeks for Xerxes to invade Greece: The enemies of the Athenians from Thessaly as well as the Pisistratidae had sent messengers to the king urging him to invade Greece.

5) Expansion of Achaemenid economic trading zones into the Mediterranean: Darius had left a powerful legacy of private enterprise, manufacturing and international commerce, with an efficient taxation system (provincial and customs) with the major proceeds of these funds being fed back into the economy. A highly efficient irrigation system allowed for agriculture to thrive in dry areas. The empire had also completed a Royal Highway stretching 2,700 km, connecting Susa in southwest Persia with Sardis in Western Anatolia. This now facilitated economic, cultural, political and military links between the Iranian plateau and Anatolia. This allowed for the creation of history’s first true common market and free trade system. There was now also a common currency, the Daric which replaced the barter system for goods and services. There was now a rise of international commerce between regions that had never directly traded before, such as Greece and Babylon. The empire was now intent to expand Darius’ “Economic Miracle” which was now placed on the eastern shores of the Mediterranean. This challenged Greek economic and shipping primacy in the Mediterranean. Note that Greeks were already established in the Mediterranean in places such as Calabria in southern Italy, Nikea (modern Nice in southern France) and Massilia (modern Marseilles, also in modern southern France). There were also many Greeks participating in the commercial benefits of the Achaemenid Empire’s economy whose ships were now expanding into the Mediterranean. Italian researchers for example have found evidence of a Persian trading colony in southern Italy dated to the times of Darius and Xerxes. Hence we can now assert that one of the facts that may have led to war was economic rivalry in the Mediterranean between Greece and Persia.

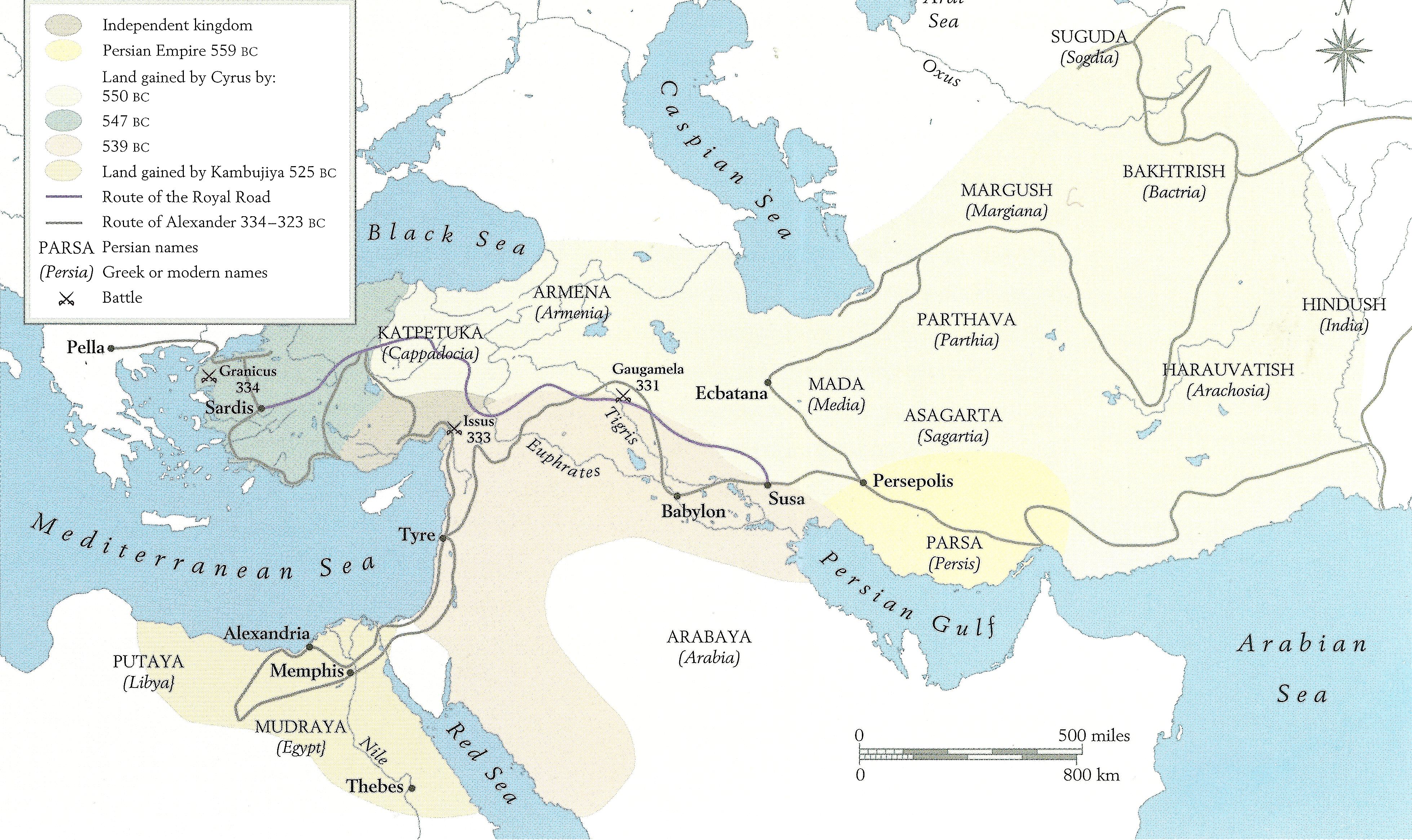

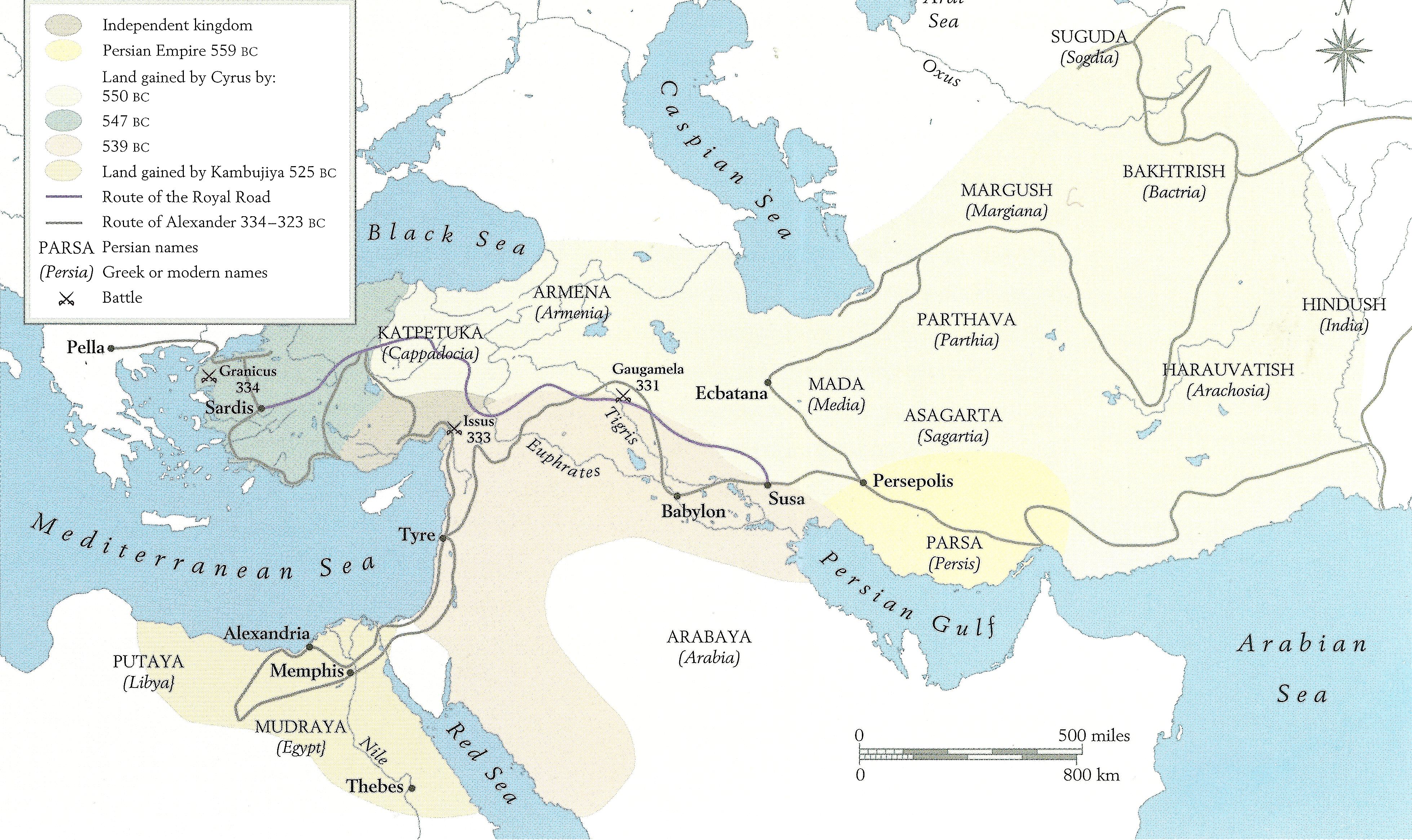

Map of the Achaemenid Empire drafted by Kaveh Farrokh on page 87 (2007) for the book Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War-Персы: Армия великих царей-سایههای صحرا-:

=============

[4] From a military perspective, What do you consider to be the greatest Persian success? And Persia’s greatest failure?

Most historians of ancient Iran would probably tell you that the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BCE in which the Roman armies of Marcus Lucinius Crassus were defeated by a smaller Parthian force was ancient Iran’s greatest victory or the victories of Sassanian king Shapur I in the early 3rd century CE over the armies of Gordian III, Philip the Arab and Valerian.

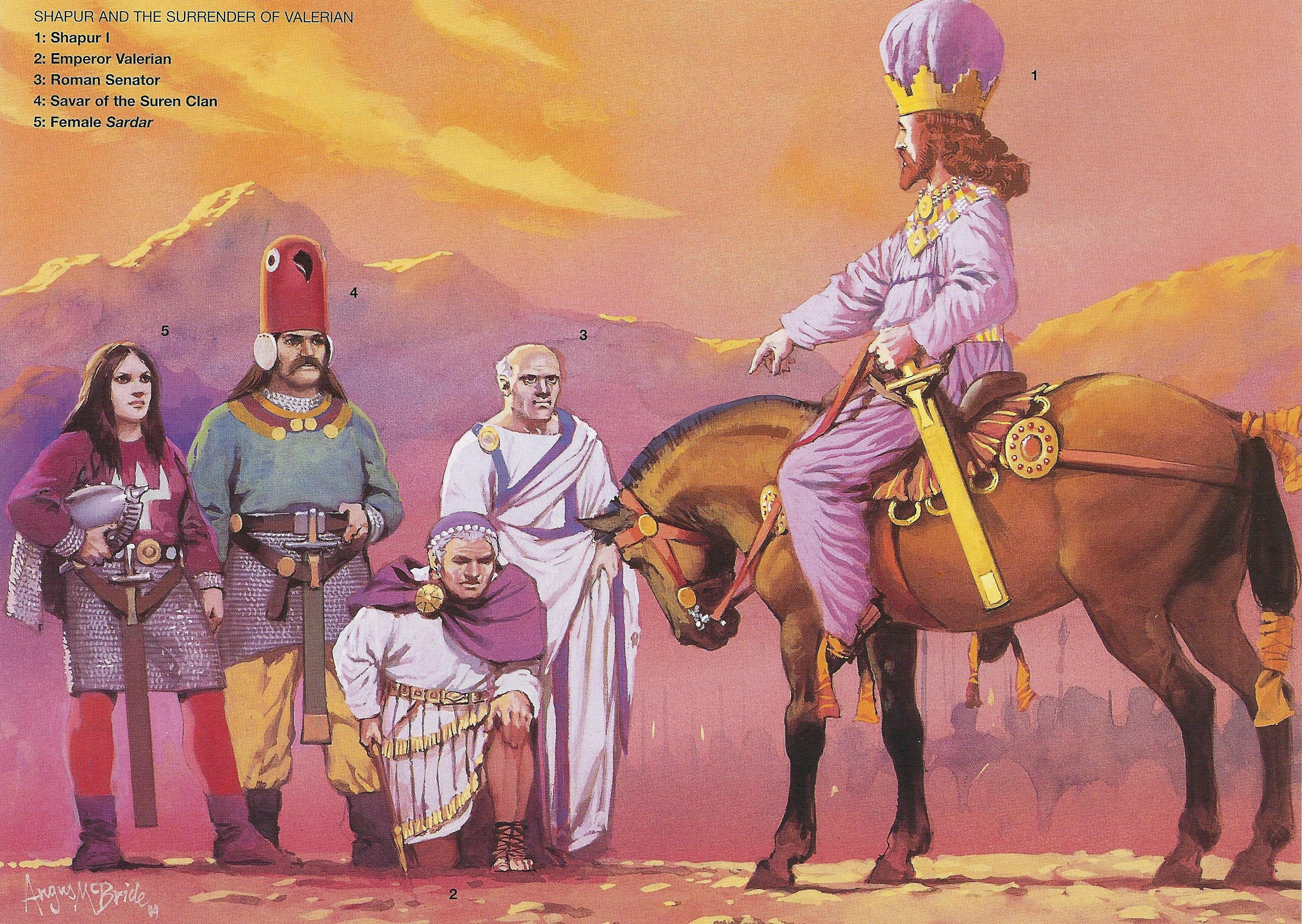

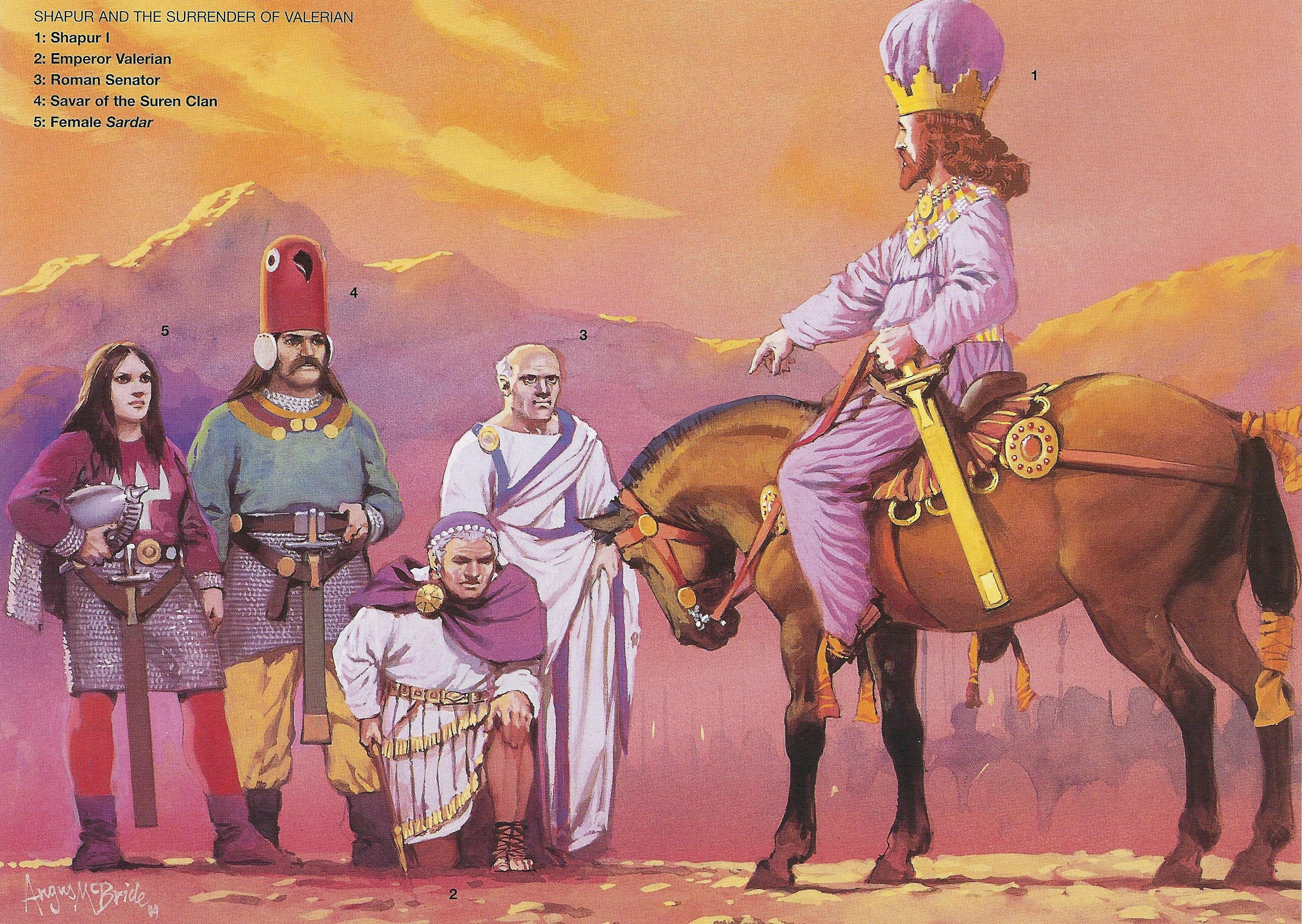

Emperor Valerian surrenders to Shapur I (241-272 CE) and Sassanian nobility at Edessa in 260 CE (Source: Kaveh Farrokh, 2005, Elite Sassanian Cavalry).

However the precursor to all of these victories is a little known Iranian commander from Central Asia known as Spitames who inflicted a decisive defeat on a Macedonian army at the Battle of Zarafshan River (known as the Battle of the Polytimetos River in Classical sources). Spitames’ victory was the result of the development of the doctrine of the all-cavalry force in which heavy armored lancers were supported by light cavalry (horse archers and javeliners). This doctrine had been developing in Achaemenid armies even as Alexander toppled the Achaemenid Empire. The concept of the armored cavalryman had continued to evolve from the Battle of Cunaxa in 401 BCE and even as Alexander advanced into Persia, the military planning staff had implemented important reforms that would eventually lead to the rise of Persia’s later Parthian and Sassanian armored lancers. It was in the armies of Spitames where the reforms of Darius III’s staff finally found their fruition, leading to defeat of the Macedonian general, Pharnacus. The Battle of Zarafshan was the prelude to the later victories such as Carrhae, those of Shapur I, etc.

Parthian Horse archers engage the Roman legions of Marcus Lucinius Crassus at Carrhae in 53 BCE. Unlike the Achaemenid-Greek wars where Achaemenid arrows were unable to penetrate Hellenic shields and armor, Parthian archery was now able to penetrate the armor and shields of their Roman opponents (Picture Source: Antony Karasulas & Angus McBride).

As per the greatest failure, many but not all of course would cite the Battle of Qadissiya in 637 CE when Arabo-Muslim invaders defeated the Sassanian armies, which led the way to the eventual capture of Ctesiphon. In my opinion that was a catastrophe that may have been averted had it not been for the wars of Byzantium and Sassanian Persia in 604-628 CE. Even as Persia was victorious for much of that conflict, especially by capturing Syria, Palestine, Egypt and much of Anatolia from the Byzantines, these same victories laid the seeds of Persia’s destruction. Persia had overextended herself militarily and when Heraclius rebuilt the shattered Byzantine armies and struck his alliance with the Khazars, the fate of the empire was in jeopardy. The ensuing counterattack proved devastating to the Sassanians who were finally forced to sue for peace with Khosrow II deposed. According to Western sources the Byzantines lost around half a million of their top warriors in that conflict and it may be safely assumed that the Sassanians had lost just as many if not more during Heraclius’ counter-strikes. Both the Sassanians and Byzantines were badly shaken to the core and militarily weakened.

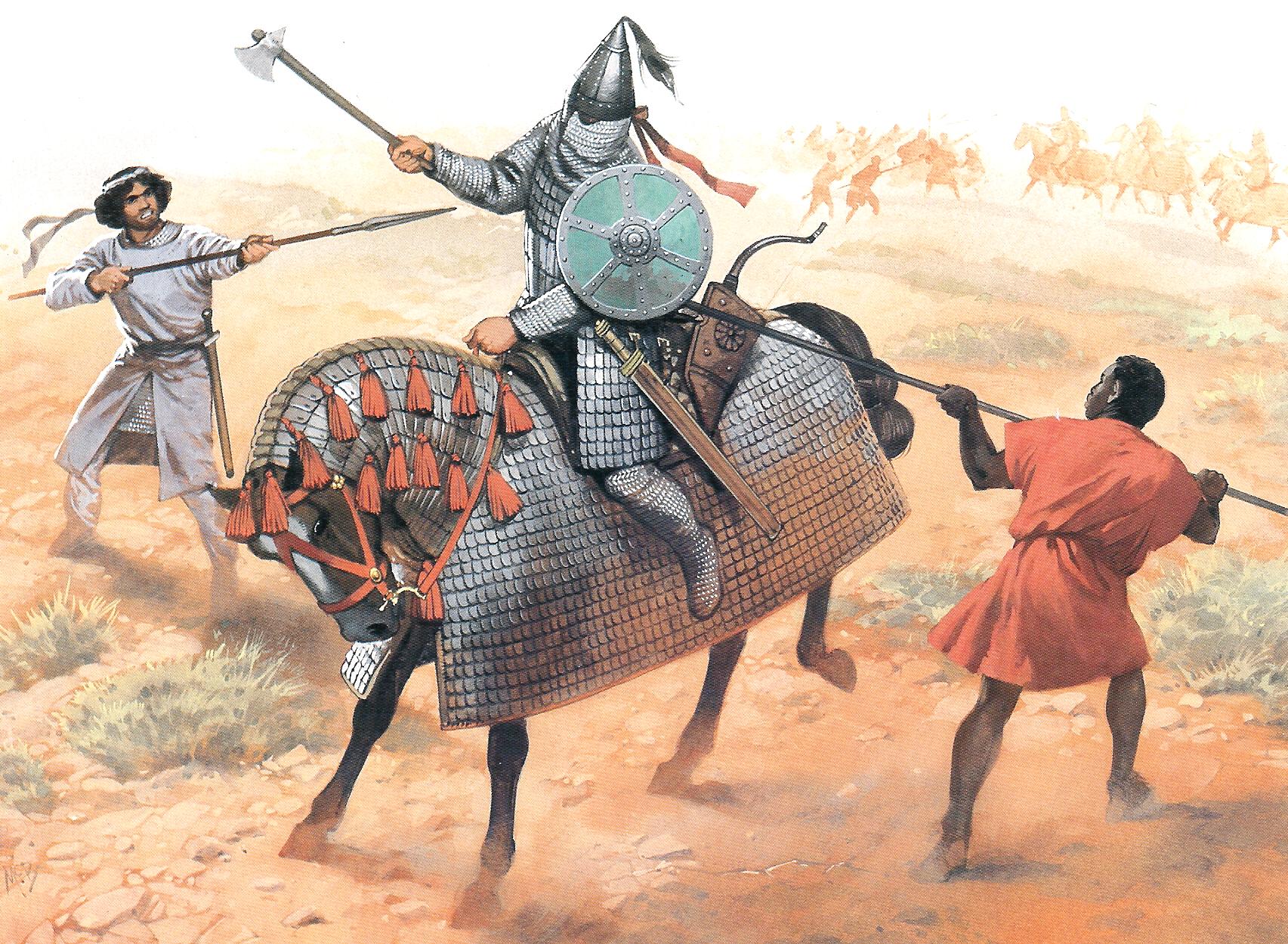

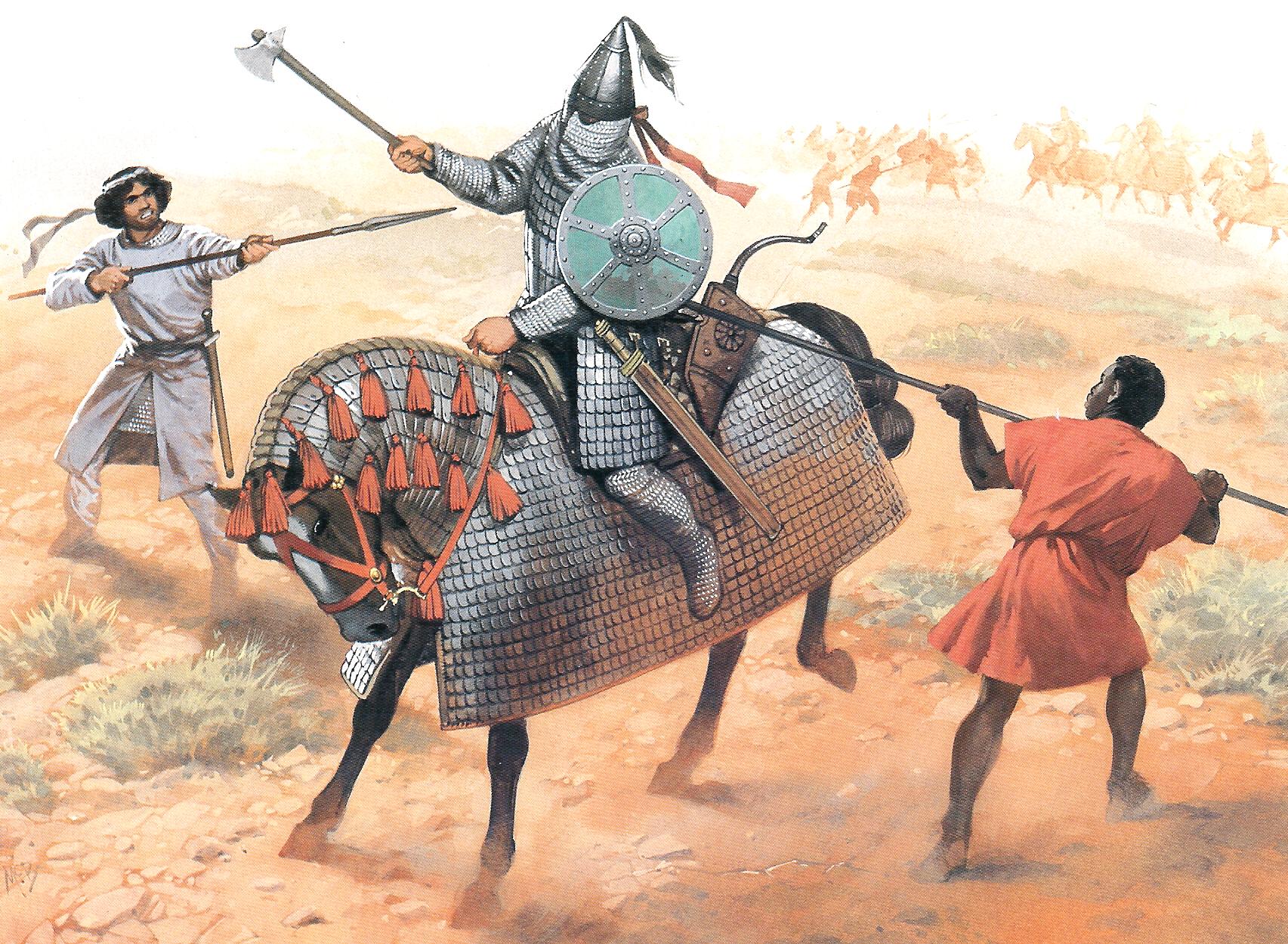

The Aftermath of the Byzantine Sassanian Wars: The Arabs strike. Tim Newark’s reconstruction of Arabo-Muslim invader and his Ethiopian slave confronting a Sassanian cavalryman at the Battle of Qadissiyah (637 AD). Despite Rustam Farrokhzad’s (the Iranian commander) best efforts, the Arabo-Muslim forces emerged victorious after a four-day battle. Key factors in the Arab victory were (1) the weakened military state of Sassanian forces after the devastating wars with Byzantium (2) general demoralization among the troops and civilians and (3) a powerful sandstorm which blew sand into Sassanian forces just as Farrokhzad was about to deliver a devastating blow. Nevertheless, Ctesiphon, the capital city of the Sassanian empire (40 kilometres from modern-day Baghdad, Iraq), put up a spirited defence against the Arabian invaders before being sacked and looted – up to 40,000 Iranian women were taken to Arabia to be sold as slaves. Byzantium also paid the price for its war with Sassanian Persia – with the exception of Constantinople and parts of Anatolia, the Arabs drove the Byzantines permanently out of the Near East and Egypt. For a full military account of these events consult pp. 268-271, Farrokh, –سایههای صحرا-Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War-Персы: Армия великих царей, 2007. (Picture source: picture 11, Tim Newark, The Barbarians: Warriors & Wars of the Dark Ages, Blandford Press, 1985 & 1988).

The new Caliphate of the Arabs ruled by Omar realized how the long Sassanian-Byzantine war had fatally weakened both empires. Omar also realized that he needed to strike quickly before either empire had time to recover. The Byzantines lost much of their possessions in the Near East to the Arabs but managed to survive until their final overthrow by Muslim Ottoman Turks in 1453. When the Arabs thrust into Sassanian Persia they were no longer facing the world-class armoured lancers that had challenged Rome for centuries but the battered remnants of a once mighty professional military force. The long Byzantine-Sassanian war in my opinion was a gross military error that not only cost the Sassanian Empire its existence but resulted in a fatal change in the history of the world. If the Byzantines and the Sassanians had made peace, the Arab-Muslims would have had great difficulty in expanding their Caliphate across North Africa and then into Spain with brief incursions into southern France. The Byzantine-Sassanian war indeed changed the face of history much as did the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

=============

[5] We are well acquainted with Persia’s relationship with the West, but do we know anything about their relationship with Eastern peoples?

When we say Persia, we need to look at the wider context of Iranian peoples and L’Iran exterier. In this context we are looking at Iranian tribal confederations such as the Scythians, Alan-Sarmatians and other North Iranian peoples who dominated much of Eastern Europe, Eurasia and Central Asia. These tribal confederations also facilitated links between their Iranian kinsmen in Persia and China and enabled links between Persia, the Caucasus, Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean. When the first proto-Iranian peoples migrated eastwards they reached as Far East as the Tien Shan Mountains. From the 2nd millennium BCE they had established trade across the Pamir Mountains between China and the Yarkand-Khotan and Badakhshan regions. This began a long and continuous process of intercultural influence between the Iranian peoples-Persia and the Chinese civilization that is also in a sense, the birth of the Silk Route that was to become the “cultural internet” of its day, linking east and west. In between the two hemispheres were located the Iranian peoples and Persia. As noted by the late Professor Berthold Laufer:

“We now know that Iranian peoples once covered an immense territory, extending all over Chinese Turkestan, migrating into China, coming in contact with the Chinese, and exerting a profound influence on nations of other stock, notably Turks and Chinese. The Iranians were the great mediators between the West and the East, conveying the heritage of Hellenistic ideas to central and eastern Asia and transmitting valuable plants and goods of China to the Mediterranean area. Their activity is of world-historical significance, but without the records of the Chinese we should be unable to grasp the situation thoroughly”.

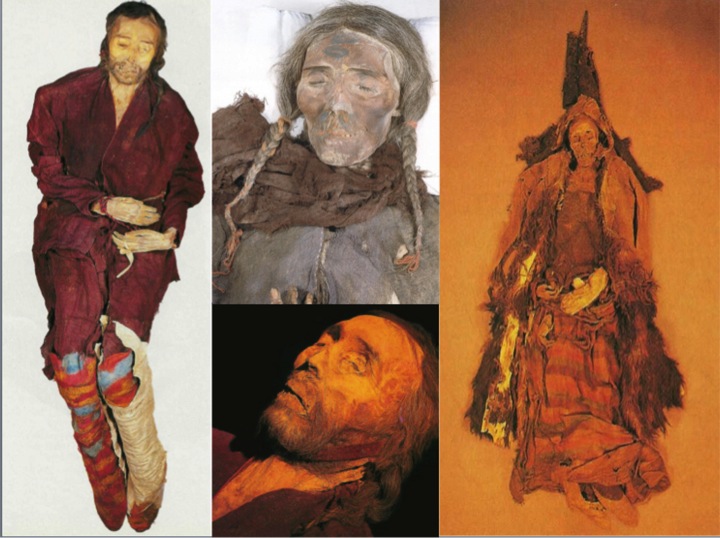

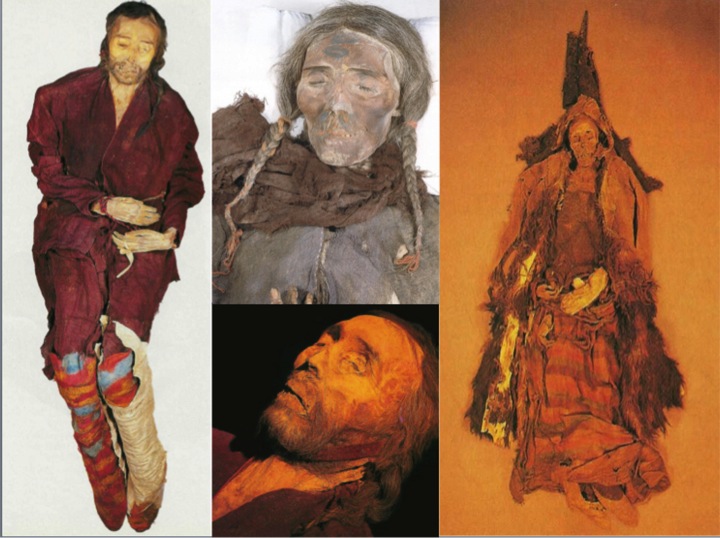

Mummies bearing Caucasoid features uncovered in modern northwest China; these were either Iranic-speaking or fellow Indo-European Tocharian (proto-Celtic?). Archaeologists have found burials with similar Caucasoid peoples in ancient Eastern Europe. Much of the colors and clothing of the above mummies bear striking resemblance to the ancient dress of pre-Islamic Persia/Iran and modern-day Iranian speaking tribal and nomadic peoples seen among Kurds, Lurs, Persians, etc. (Source: Kaveh Farrokh’s lectures at the University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division – this was also presented at Stanford University’s WAIS 2006 Critical World Problems Conference Presentations on July 30-31, 2006, the annual Tirgan event at Toronto (June, 2013) and at Yerevan State University’s Iranian Studies Department (November, 2013) – Diagram is Copyright of University of British Columbia and Kaveh Farrokh).

Perhaps one of the most interesting recent finds (report in China News in August 2014) pertains to archaeologists in Northwest China’s Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region having discovered major Zoroastrian tombs, dated to over 2,500 years ago corresponding to the chronology of the (first) Persian (Achaemenid) empire. As noted by Chinese archaeologists in the China News outlet:

“This is a typical wooden brazier found in the tombs. Zoroastrians would bury a burning brazier with the dead to show their worship of fire. The culture is unique to Zoroastrianism.”

Archaeologists in Northwest China’s Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region have discovered major Zoroastrian tombs, dated to over 2,500 years ago. (Caption and Photo Source: Chinanews.com). As noted in the China News report: “This is a typical wooden brazier found in the tombs. Zoroastrians would bury a burning brazier with the dead to show their worship of fire. The culture is unique to Zoroastrianism…This polished stoneware found in the tombs is an eyebrow pencil used by ordinary ladies. It does not just show the sophistication of craftsmanship here over 2,500 years ago, but also demonstrates the ancestors’ pursuit of beauty, creativity and better life, not just survival. It shows this place used to be highly civilized”.

Iranian peoples such as the Kushans and Parthians played a major role in the spread of Buddhism into mainland China. Too numerous to cite here are artistic legacies of that influence such as the fresco along the Tarim Basin, China depicting a Central Asian Buddhist monk instructing a Chinese monk on philosophy (c. 9th-10th Century). Influences from Sassanian Persia in China continued after the Arab conquests.

Statue of King Kanishka I (c. AD 127–163) of the Kushan Empire (c. 30-375 CE) (housed in the Mathura Government Museum, India; Source: Public Domain). The large broadsword was a powerful cultural symbol in the martial cultures of the Iranian kingdoms as exemplified by the “broadsword” of Khosrow II seen at the top panel inside the Iwan at Taghe Bostan near Kermanshah in Western Iran.

Cosmopolitan Chinese cities such as Chang’An, Lo-Yang and Tun-Huang were soon settled with vibrant Iranian immigrants as they also did in Turkish ruled Kashgar and Khotan in Central Asia. Chinese archives such as the T’ang Shu records of the court of Ming Huang or example, provide some insight into these new Iranian arrivals into China:

“Inside the (Ming Huang) palace, Iranian music is held in high esteem, the tables of persons of noble rank are always served with Persian food, and the women compete with one another in wearing Persian costumes…”

There are also a number of Chinese descriptions of Sassanians who had taken sojourn in China, such as the women of the Po-sse (Persians) often being described as having fair skin, blue or green eyes with dark or auburn hair. The Iranians also introduced the Persian Gardens dating to Cyrus the Great to China, with one exceptional example being the 17th century park of Ch’ing Emperor K’ang Shi having been inspired by the ancient Persian model.

The first Iranians also arrived as far away as Japan in the 8th century CE. The Japanese Emperor Shomu appointed Tajihi no Hironari as ambassador to T’ang China 733 CE. This was followed by the return of vice-ambassador Nakatomi no Nashiro to Japan three years later, with a large Tang delegation accompanied by a Persian known as “Li Mi-I”. Excluding the possible exception of northern Japan’s indigenous Ainu population, this is the first official record of a Caucasian visiting Japan. Most likely he was a descendant of one of the Iranian or post-Sassanian refugees to have escaped the Arab occupation of Persia and Central Asia.

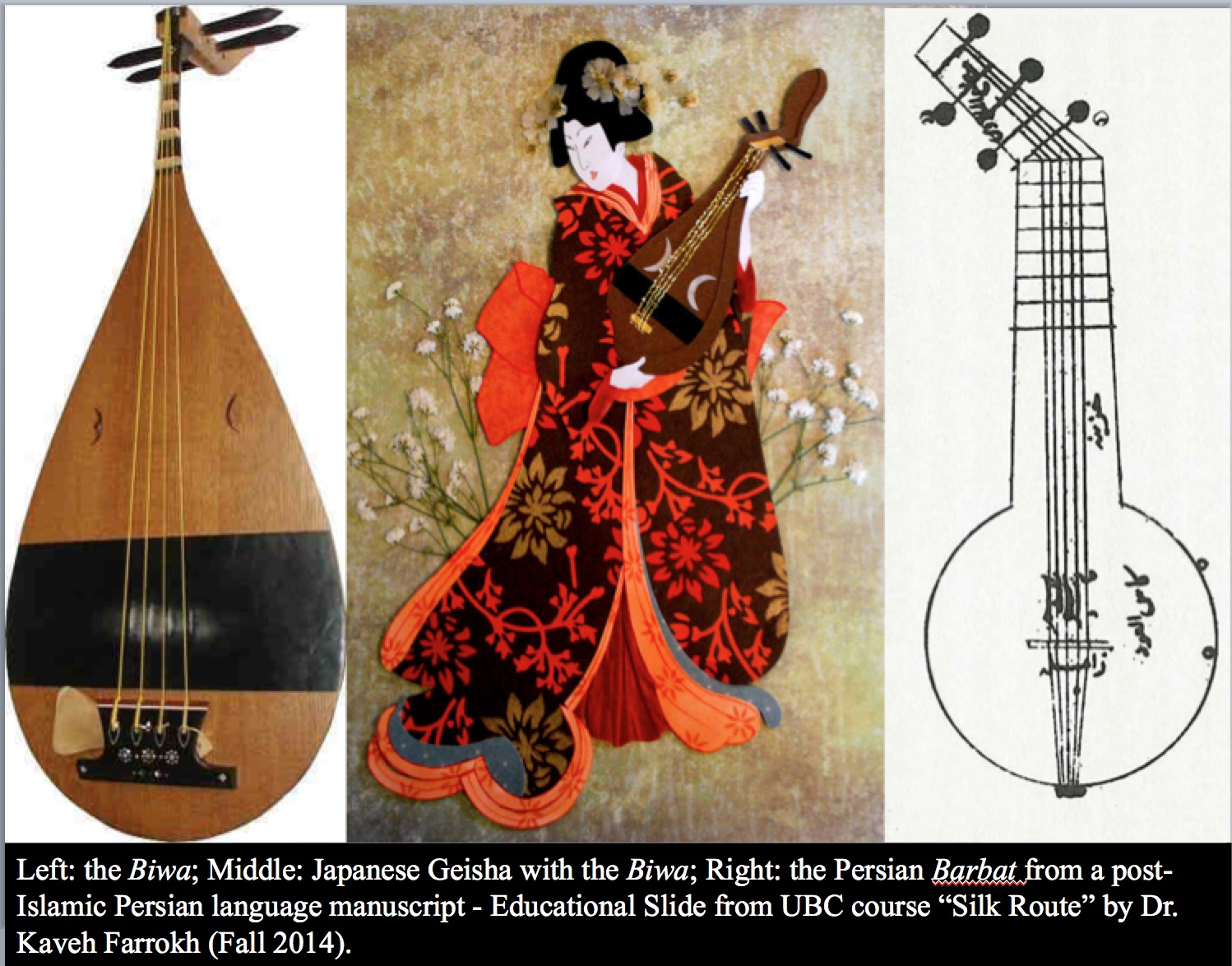

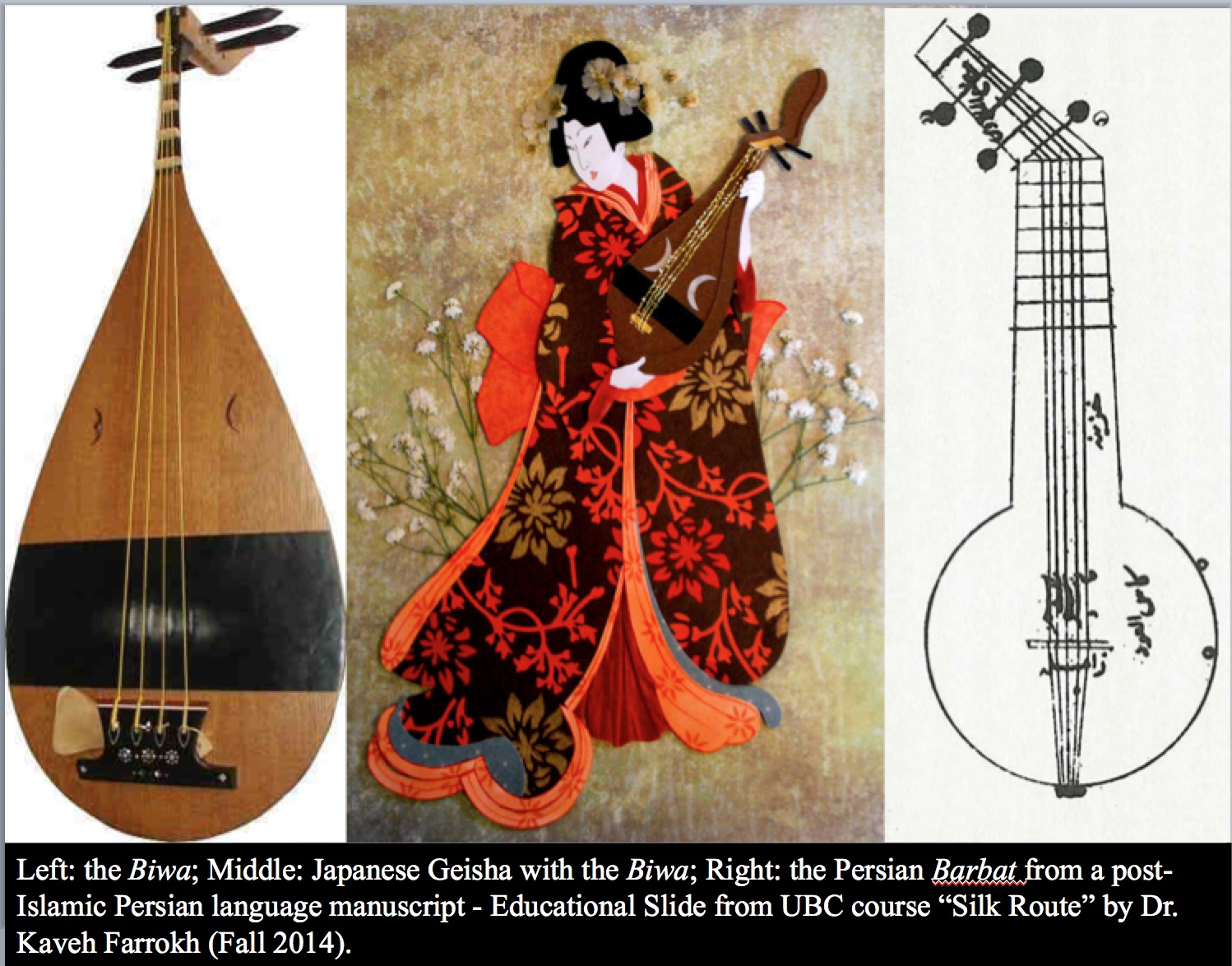

An enduring Sassanian legacy in Japan: the Biwa and its ancient Iranian ancestor, the Barbat (Source: Lecture slide from Kaveh Farrokh’s lectures from the course “The Silk Route: origins & History“).

Records of Japanese persons of Persian descent continue to be cited by Japanese researchers. Akirhiro Watanabe of the Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties for example, reports of a man who taught mathematics in Japan due to Persia’s renowned expertise in the subject – as noted by Watanabe to the Japan Times (October 2016):

“Although earlier studies have suggested there were exchanges with Persia as early as the 7th century, this is the first time a person as far away as Persia was known to have worked in Japan… This suggests Nara was a cosmopolitan city where foreigners were treated equally”.

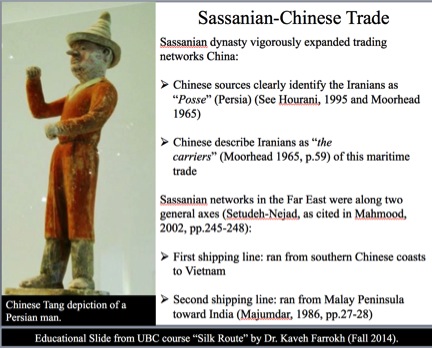

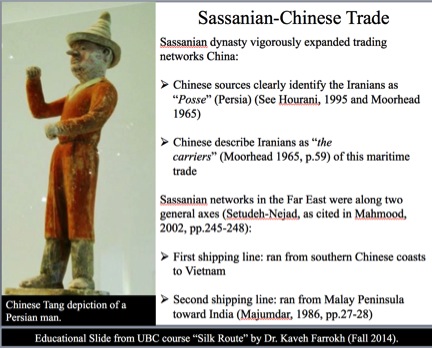

Sassanian and Soghdian merchants were actively trading with China, a process that led to Iranian links with ancient Korea and Japan (Source: Fall 2014 course on the Silk Route at the University of British Columbia).

There are also routes of cultural influence through Persian shipping extending as far away as Southeast Asia. Parthian merchants were present in modern-day Tun-Sun on the Malay Peninsula with Iranian traders recorded as far away as Tonking as early as the 3rd century CE. By the time of Khosrow I, Persian shipping technology had advanced considerably with reports of these vessels being capable of transporting up to 700 passengers and crew in addition to “a thousand metric tons of cargo“. One of the first Sassanian shipping lines ran from the southern Chinese harbors to Vietnam which was to became a major node of cultural communication in the Far East and Sassanian Persia. Sassanian coins dated to the 5th century CE for example have been discovered in Yarang, Thailand.

Iranian settlers also reached Cambodia where some Sassanian works were translated into Cambodian (known to the local Champa dynasty 192-1471 CE as “The Book of Anoushirwan” – note that Anoushirwan was the nickname of Sassanian King Khosrow I). The modern-day “Orang Bani” of southern Vietnam claim descent from the “Noursavan“, with direct references to Khosrow I also existing in ancient Malaysia (where he is referred to as “Raja Nushirwan Adil” – Malay: King Anoushirwan the Just) in the Malay literary work known as “Sejara Melayu”.

The Shalimar Bagh (Garden) of Srinagar, Kashmir constructed in the Mughal-era Persian architectural style featuring fountains, canals, pools, patterned flower works, grasses, trees, etc. (Source:Tripadikberadik).

Sassanian shipping continued to facilitate the spread of Persian culture as far as the coastal areas of southern India, China, modern Vietnam and the Pacific. Persian ships for example are reported in Sri Lanka as early as the 6th Century CE with these links continuing after the fall of Sassanian Persia to the Arabs. In fact by the 7th century CE Persian shipping had reached into the southern Pacific as attested to by records of Persian merchant ships departing from Malay towards Ceylon in 727 CE. Chinese sources record of the ships of the Po-sse (Persians) sailing from Canton in 671 CE. A large Po-sse community is also recorded in Hainan, China as late as 748 CE.

=============

[6] The Great King was the “King of Kings” (Shahan-Shah). What was the government and administration in ancient Persia? Moreover, it seems that since the third century, at the administrative level, Persia is more like Rome.

[6] The Great King was the “King of Kings” (Shahan-Shah). What was the government and administration in ancient Persia? Moreover, it seems that since the third century, at the administrative level, Persia is more like Rome.

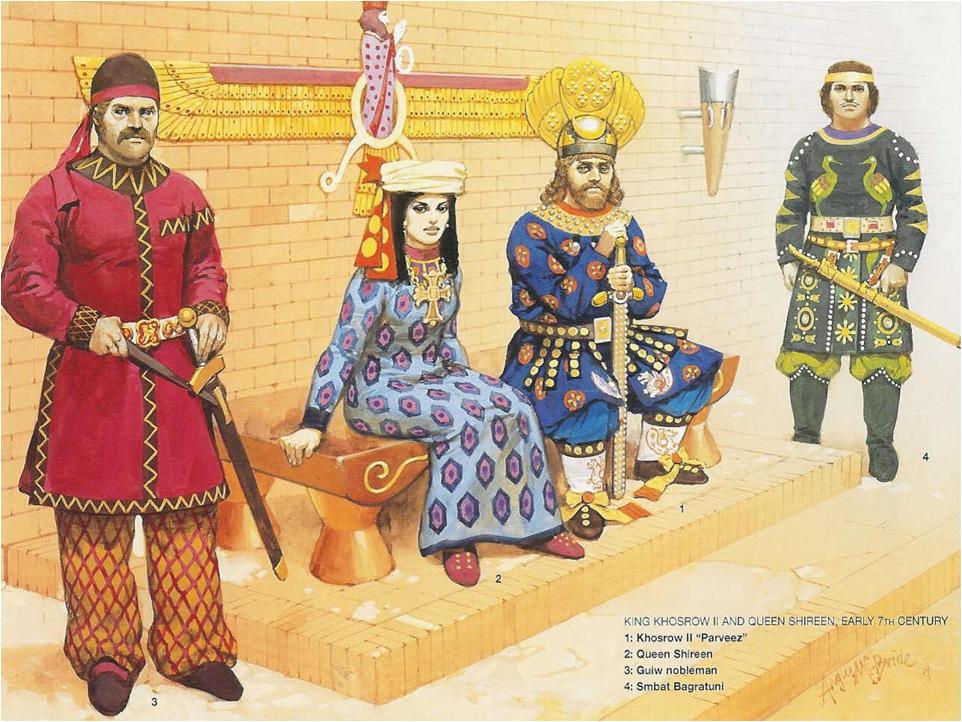

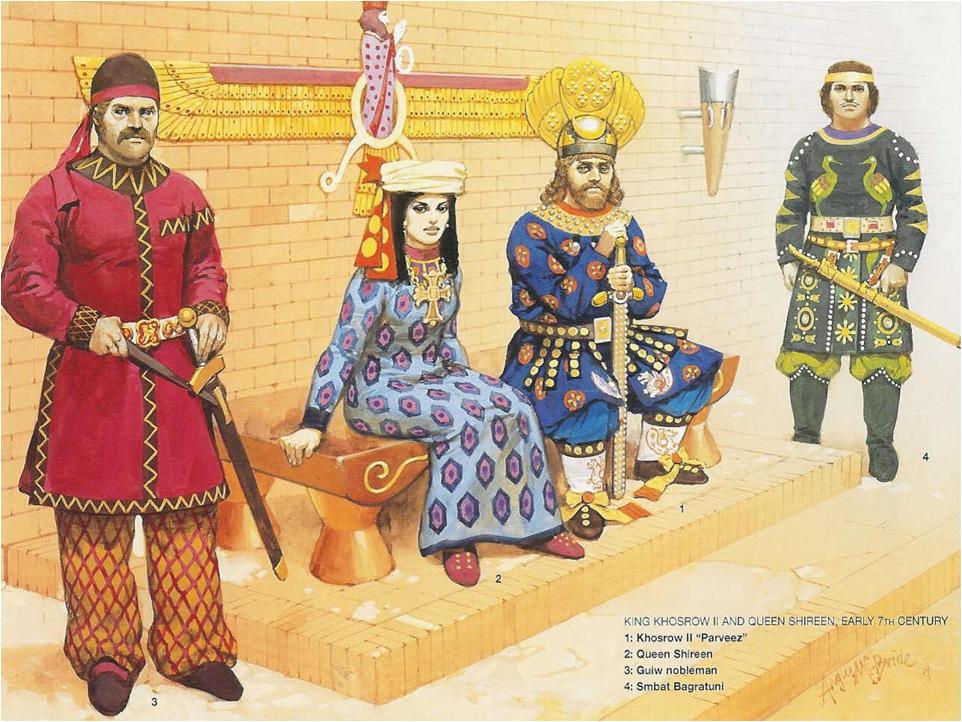

This comes back to how deeply the two civilizations (Greco-Roman and Iranian) impacted one another. The Romans themselves had inherited many of ancient Iran’s traditions, one example being the postal system, but it is in their cosmopolitan nature where the two empires shared a common image. Both Rome and Persia were civilizations that had a diverse range of peoples, languages and religions under their rule. The Sassanian Empire, like that of Rome, was multifaceted with the characteristic of having had distinct (social) classes organized into a hierarchical order. It seems that there were four distinct social classes: (1) the priests or Magi known as the “Asronan” (2) the professional warrior class which was recruited from the higher nobility of “Wuzurgan” (grandees) and especially the “Azadan” (lit. freemen) but following the reforms of the 6th century CE, there was also a new class of cavalry of the “Dehkans” or lesser nobility (3) the class of commoners or the “Wastaryoshan” and (4) the lowest class of “Hutukhshan” (artisans). At the apogee of supreme authority was the Shahanshah (king of kings) much like the Emperor of Rome. The king’s entourage was composed of the Wuzurgan (grandees) who were composed of lesser rulers/kings, princes from the house of Sassan, the Magi or priests and the great landlords.

court of Khosrow II and his queen Shirin (Source: Farrokh, Plate F, p.62, -اسواران ساسانی- Elite Sassanian cavalry, 2005); note the monarch who sits with his ceremonial broadsword. The Sarmatians shared the culture and martial traditions of their Iranian kin, the Parthians and the Sassanians.

While both the Romans and the Sassanians shared parallels in their administration, the two empires also shared certain parallels in religious development. As you know the Roman Emperor Constantine did much to promote Christianity as a single religion for the Roman Empire. Constantine and his son Crispus sat in on the Council of Nicea in 325 CE to provide the ecumenical foundations for a single form of Christianity much as during the Sassanian era, notably from the time of the Grand Magus Kartir, Zoroastriansim was to become increasingly an orthodox faith for the Sassanian Empire. Note that a similar process had occurred in another earlier Iranian empire: the Kushans. Kanishka the Great, Kushan’s greatest emperor, presided over the 4th Buddha Council to meet in the Punjab (or Kashmir?) to harmonize the doctrines of 18 opposed (Buddhist) sects, thereby promoting the Kandahara School of Buddhism. Religion was now one of the institutional pillars for administrating a vast empire, in this case with respect to the empires of Rome, Persia and the Kushans.

=============

[7] If the Sassanid Empire managed to resist the invasion of Heraclius, How did they fall quickly before the Arabs?

This has been discussed in detail in my 2017 textbook on the Sassanian Army, and here we can give you a concise summary. Three of the reasons for the Sassanian collapse are listed below:

Military factors. This part of the interview connects to what we discussed in response to Question 4. The devastating Sassanian war with the Roman-Byzantines badly damaged the efficiency and morale of the Sassanian Spah (army). As noted previously the huge losses in professional warriors meant that the Arabs no longer had to fear facing Persia’s top fighters. Persia needed a generation to recover its losses and to train replacements for its missing ranks of top-level professional warriors. The caliphate led by their caliph Omar, had no intentions of giving the Persians or Romans any time to recover – less than 10 years after the ceasefire between Persia and Rome, the Arabs struck both empires. Before the invasion, morale and discipline had also plummeted in the Sassanian army which also affected vigorous training. Put simply, the Arabs had great timing in their history: they struck at the right place and at the right time against Persia and Rome. And the results of this, as we noted before, were devastating with the road to Europe opened allowing the Arabs to invade Spain.

Frictions in the upper classes. The upper stratum of Sassanian society had rifts, especially between those of Parthian descent and the house of Sassan. Parvaneh Pourshariati has outlined in detail how these dynamics helped weaken the ability of the Sassanian state to resist and endure against the Arab invasion. Loyalty was also an issue when the Arabs invaded, as numbers of the top nobility and military personnel joined the Arabs during the invasion. Sassanian warriors who joined the Arabs were often paid twice (or more) the salary than regular Arab troops!

Societal: the Sassanian class system was rigid, so upward mobility was very difficult. There was also the problem of the extremely wealthy upper classes, especially landlords, who along with the Royal House, were hoarding a larger and larger share of the nation’s wealth at the expense of the ordinary people. In short, there was a wide gap between rich and poor. The reformer-prophet Mazdak had attempted to address these societal imbalances at the time of king Kavad (reign: 488-496, 498-541 CE) but by the time of his son Khosrow I (reign: 531-579 CE), Mazdak was executed and his followers suppressed. Despite economic advancement and reforms by Khosrow I, the challenges facing Sassanian society had not been completely addressed by the time the Arabs were preparing to invade the Sassanian Empire.

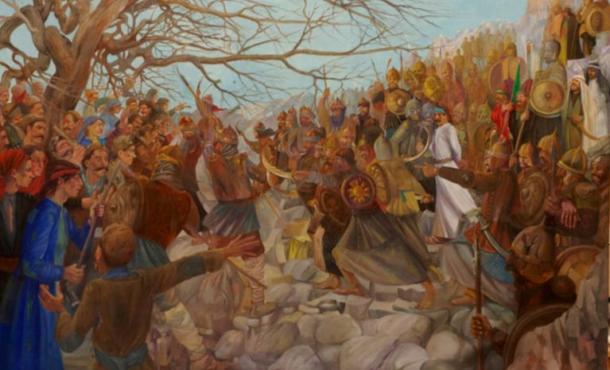

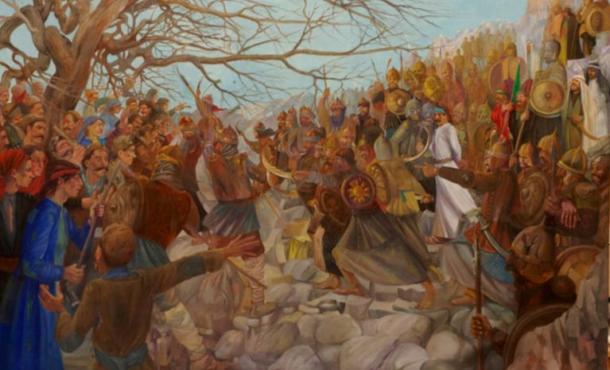

Re-enactment of Battle of Qadissiyah (Source: Umar Ibn Khattab Series MBC1 & Qatar TV).

However Persia did not fall as quickly as many believe. While true that Persia was conquered, fierce resistance against the Arabs continued well into the 9th century CE. There were many Iranian resistance fighters such as Sindbad, Muqanna, Ustasis, etc. There are several women resistance fighters who fought against the Arabs, one of these being Azadeh Dailam (the free of one Dailam) hailing of a Parthian clan. She held the Arabs at bay in northern Persia. Remarkable is also the exploits of Babak Khorramdin who with his wife, Banu, who led a nearly three-decade resistance movement, having ejected the Caliphate from northwest Persia. This led to the arrival of thousands of anti-Caliphate fighters from across Persia to join Babak’s banner. Babak also made a joint declaration with Maziar (a prince from the Parthian Karen clan) and Afshin (an Iranian general) stating that they intended to: “…take back the government from the Arabs and give it back to the Kasraviyan [Sassanians]”.

The Castle of Babak Khorramdin in Iran’s Azarbaijan province which defied the armies of the Caliphate for two decades (Source: Ancient Origins).

Babak and Banu are Persia’s equivalents to Spain’s King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella. Just as Ferdinand and Isabella succeeded in breaking the hold of the Caliphate in Spain, so too did Babak and Banu endeavour to eject the Caliphate from all of Persia. Several armies of the Caliphate were wiped out by Babak’s fighters in 813-833 CE, however the Byzantine Empire failed to capitalize on these successes to help the Iranians, and with the end (some would say betrayal) of his resistance movement in 837 CE, Persia’s last chance to eject the Caliphate ended.

Iranian painting of 2009 depicting the betrayal and capture of Babak by the caliphate (Source: Ancient Origins).

Nevertheless, the Arabs failed to impose themselves in northern Persia. Ibn Isfandyar’s “History of Tabaristan” provides a number of detailed observations of the local armies in northern Persia, which appear to have retained Sassanian military tactics, equipment and titles. One of the local commanders of northern Persia, Sherwin Ispadbodh, reputedly refused to allow any slain Muslim Arabs to be buried in northern Persia. Arab sources can be cited describing Northern Persia as one of the implacable enemies of the Caliphate. This was at a time when Spain had fallen to the Arabs in Europe. More examples of resistance in the interior of Iran can be cited, but suffice it to say that Iran, like Spain, refused to become Arabicized in culture and language, a fate that befell ancient peoples such as those of Egypt, Syria, Phoenicia and many others. It was Spain and Iran that succeeded in retaining their distinct culture and Indo-European languages. Neither Spain nor Iran are Arab countries today.

=============

[8] After the Arab conquest, were there remains of Persian culture?

Here is a case that defines the endurance of Persia: she gets conquered but her culture not only endures but conquers that of the invaders: the Arabs of the Caliphates followed by the Seljuk Turks and the Mongols. Here is where a quote by the Arab historian Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406) in his Muqaddimah (translated by F. Rosenthal (III, pp. 311-15, 271-4 [Arabic]; R.N. Frye (p.91) which has acknowledged the role of the Iranians in the promotion of scholarship in the post-Sassanian era:

“…It is a remarkable fact that, with few exceptions, most Muslim scholars…in the intellectual sciences have been non-Arabs…thus the founders of grammar were Sibawaih and after him, al-Farisi and Az-Zajjaj. All of them were of Persian descent…they invented rules of (Arabic) grammar…great jurists were Persians… only the Persians engaged in the task of preserving knowledge and writing systematic scholarly works. Thus the truth of the statement of the prophet becomes apparent, ‘If learning were suspended in the highest parts of heaven the Persians would attain it”…The intellectual sciences were also the preserve of the Persians, left alone by the Arabs, who did not cultivate them…as was the case with all crafts…This situation continued in the cities as long as the Persians and Persian countries, Iraq, Khorasan and Transoxiana (modern Central Asia), retained their sedentary culture.”

A statue of Arabo-Islamic historian, Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406) in Tunisia. Ibn Khaldun emphasized the crucial role of the Iranians in promoting learning, sciences, arts, architecture, and medicine in Islamic civilization. It was pan-Arabists such as Sami Shawkat who insisted that history books such as those by Ibn Khaldun be destroyed or re-written to remove all references of Iranian contributions to Islamic civilization. The former Baathist regime in Iraq promoted such policies and even worked alongside numerous lobbies to promote historical revisionism at the international level.

As per the Turks, let us refer to Turkish Professor Ilber Ortayli of Galatasaray University (Istanbul, Turkey) in his interview with the BBC-Persian news outlet (October 2012):

“The influence of Iran upon the Turks is like the influence of ancient Greece upon the entirety of Europe … We [the Turks] adopted much of our bureaucratic and governance methods from the Iranians during the Ottoman dynasty. We have been influenced by Iranian civilization since ancient pre-Islamic times. The only difference between us [the Turks] and them [the Iranians] is in our language groups…Persian is an Aryan language … Our worship of nature and creed of Shamanism has been heavily influenced by Zoroastrianism. And in the days of Islam, all of our learned men/teachers who taught us were all Iranians. Even our alphabet is derived from the Iranians…because of our history with the Ottomans we continue to share a special bond with the Iranians”.

History Professor Ilber Ortayli of Galatasaray University in Istanbul Turkey.

The Turks and Iranians hence share what is known in Iranian Studies as “Persianate Civilization”, a culture pervading among the Iranian-speaking Kurds, the Caucasus, Afghanistan and Central Asia. As this pertains to a shared general culture that transcends ethnicity, language and religion, thus this is not the same as “Muslim Civilization”. Georgia and Armenia for example are predominantly Christian nations yet both have strong traces of Persianate influence. Large but as yet unspecified numbers of Kurds do not profess Islam either, these often following ancient Iranian cults (e.g. the Yaresan, Yazidi, Ahl-e-Hak, etc.).

So we can end this part of discussion by saying this: while Iran did fall under the boot of conquerors such as the Arabian Caliphate, the Seljuk Turks and Mongols, the nation retained its Indo-European character and was neither Arabized nor Turkified. Again as noted in my response to question 7, the closest historical parallel in Europe is that of Spain which also fell under the to the Arabian Caliphates, but she, like Persia, succeeded in retaining her (Indo-)European language and culture.

=============

[9] If you had to choose a moment from the History of Persia (pre-Islamic), what would it be?

Cyrus the Great’s edict declaring the human rights of diverse peoples and religions. Perhaps this is best expressed in my 2013 article on this topic published in the special edition of the Fezana (Publication of the Federation of Zoroastrian Associations of North America) Journal on Cyrus the Great and the Cyrus Cylinder in 2013. This edition featured articles written by a variety of scholars such as Jamsheed Choksy, Jacob Wright, Jenny Rose, Lisbeth Fried, Marc Gopin and Mohamad Tavakoli-Targhi.The entire journal’s articles have also been translated into Spanish. Greek, Babylonian and biblical sources agree on Cyrus’ benevolent statesmanship but given the vastness of the subject we can cite the example of his rule as laid out in the declarations of the Cyrus Cylinder: (a) the Babylonian god Marduk is to be respected, a clear signal that Cyrus had not arrived in the city of Babylon on October 29, 549 BCE as a conqueror to impose Iranian culture, theology, and language (b) ordering a slum-clearance program, clearly demonstrating Cyrus’ concern for the welfare of all citizens irrespective of wealth, status, ethnic origin, religion, etc. (c) statues of gods of all religions were to be restored in original locales in accordance with the wishes of the people, a clear reference to freedom of worship, much like that enshrined in the Constitutional declarations of the Founding Fathers of the United States and (d) the right of all citizens to again engage in their respective New Year festivals, thereby affirming the rights of all citizens to freely and proudly celebrate their respective cultures.

The Cyrus Cylinder (The British Museum)

This is also the first time in history that a world power, Achaemenid Persia (550-333 BCE), had guaranteed the welfare of the Jews by protecting their culture, customs and religion. Liberated by Cyrus, perhaps up to 40,000 Jews now returned to Jerusalem from their Babylonian captivity who were even given funds from the Persian treasury to rebuild their temple. This policy is seen later with Darius the Great in 519-518 BCE who continued his support for the rebuilding of the Jewish temple at Jerusalem. An indication of the importance of Jews in the Achaemenid Empire is perhaps provided by the roles of Ezra, Daniel and Mordechai as described in the Bible. Thus to me, Persia’s finest hour is traced to Cyrus himself, as his real mark in history was not in military conquest, but in the way he chose to govern his newly formed empire.

=============

[10] Your 2008 book Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War has become a benchmark for studying Persia from a more objective view – and was celebrated by Richard Frye – However there are still many prejudices about ancient Persia. Do you think that the fall of the Shah helped to increase that image of Iran as an enemy of the West?

[10] Your 2008 book Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War has become a benchmark for studying Persia from a more objective view – and was celebrated by Richard Frye – However there are still many prejudices about ancient Persia. Do you think that the fall of the Shah helped to increase that image of Iran as an enemy of the West?

The late Professor Richard Nelson Frye (1920-2014) was a mentor and guide to me in many ways and in a sense, my second book (Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War) has been dedicated to his lifelong work in resurrecting a part of human civilization and history that has been marginalized for far too long.

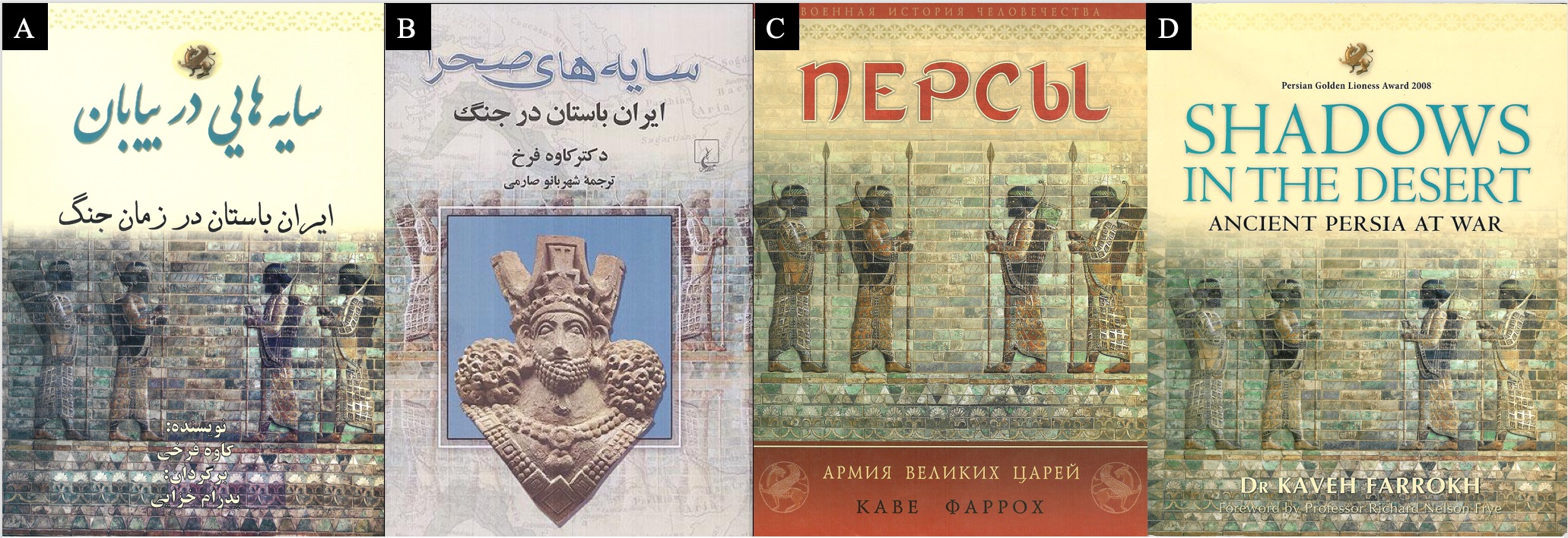

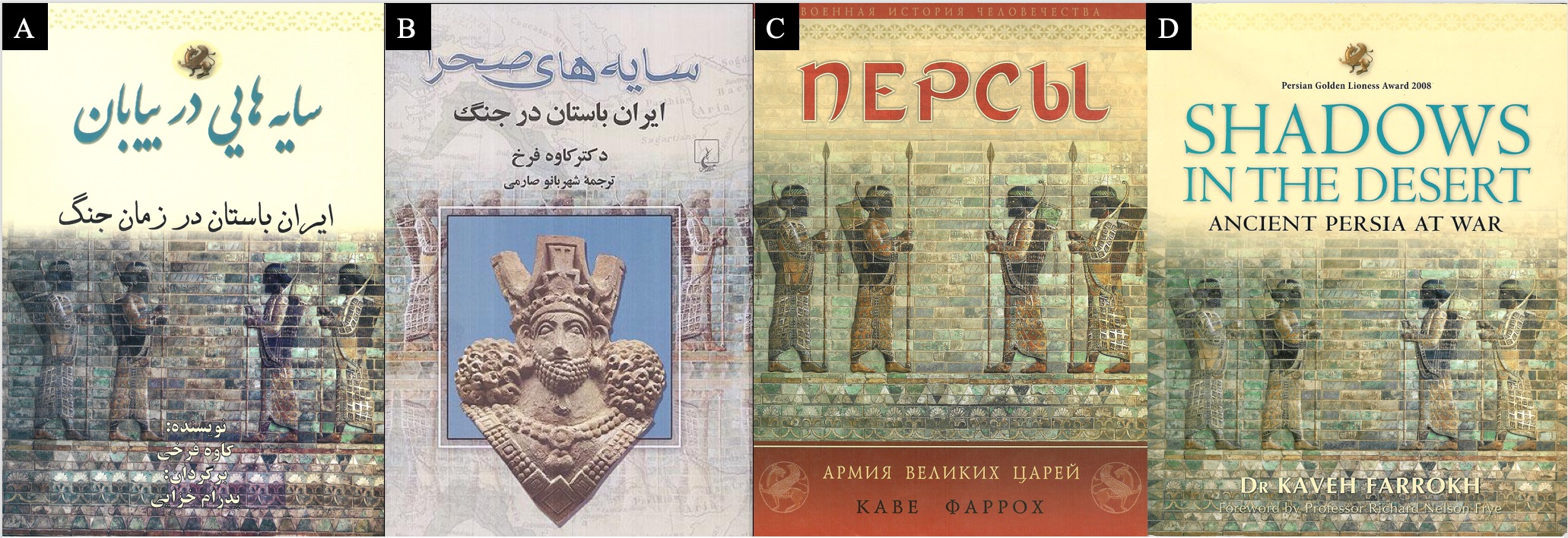

Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War – [A] Persian translation by Taghe Bostan Publishers with the English to Persian translation having been done by Pedram Khazai; [B] Persian translation by Qoqnoos Publishers with the English to Persian translation having been done by Shahrbanu Saremi; [C] the Farrokh text translated into Russian (consult the Russian EXMO Publishers website); [D] The original publication by Osprey Publishing. As noted by the Iranshenasi academic journal, Professor Frye of Harvard University wrote the foreword of Farrokh’s text stating that “…Dr. Kaveh Farrokh has given us the Persian side of the picture as opposed to the Greek and Roman viewpoint …it is refreshing to see the other perspective, and Dr. Farrokh sheds light on many Persian institutions in this history…” (Mafie, 2010, pp.2).

In many ways you are correct as since the fall of the Shah in 1979, there had been an endless barrage of negative reports regarding Iran. But is this really only the result of the revolution? In reality Iran was already the target of negative reporting even before the fall of the Shah. While I do wish to go off topic, the issues with Iran are mainly based on geopolitical and especially petroleum issues, no matter what government is ruling in Iran (the Pahlavi Shahs or the current Mullah theocracy).

I recall growing up in Europe in the 1970s and seeing the almost daily barrage of anti-Iran reports in television documentaries and news reports. Some reports that come to mind are those of the American CBS station’s 60 Minutes or the Welt Spiegel from West Germany in the 1970s which always seemed to amplify Iran’s problems and faults but seemed to turn a blind eye to the issues of other neighbouring countries. For example there were constant reports from Amnesty International and Human Rights groups regarding Iran, yet far less mention was made when it came to any of Iran’s neighbours or the wider Middle East region. Even to this day reporting is often absent on these issues in the Arab world: the lack of elections in many Arab countries, women’s rights, human rights violations, etc. Take the case of Yemen for example: when Egypt’s Gamal Abdul Nasser invaded the country, there was hardly any reaction from the Western press or political outlets. And today, Yemen, the poorest country in the Arab world, is again being crushed, this time by the mighty military machine of the Saudis, an epic human disaster with looming famine and disease. Yet there is very little criticism of Riyadh – to the contrary, they are even armed with the latest Western weaponry. Iran’s Mullah theocracy is far from innocent of course and while much of the criticism against this regime would be valid, why the silence then when it comes to Iran’s neighbors whose regimes are not necessarily better?

I still recall the outcry when the late Shah celebrated the 2,500th anniversary of the Persian monarchy. It was complained that this was an extravagance when much of the country struggled with poverty. However hardly any mention was made on the fact that the vast proportion of the funds were actually invested not on the celebrations themselves but on infrastructure projects such as highways, lodges, hotels, etc. Contrast this with the (far greater) extravagances of the wealthy sheiks neighboring Iran, a fact that continues to this day, yet there are hardly any Western reports of the vast gap between rich and poor in the Arab world.

It seems that Iran has become, as the French would say a favorite “bête noire”, even if the facts do not fit the narrative. On this note, allow me to share a personal experience I had while being interviewed by a radio station in the US. I was initially invited to speak regarding my third book Iran at War: 1500-1988 (published in 2011) but the radio host apparently had another intention: his paradigm was that Iran has been an enemy of the West since the dawn of history. It is clear that he had not read the textbook, especially the section on the Safavids that details how the Europeans and Persia were allies against the Ottoman Empire, the seat of the Caliphate at the time. I described to the radio host many of the items mentioned in our present interview (the links between civilizations, Iran’s Indo-European heritage) and especially the fact Persia was viewed very positively in the West including the founding fathers of the United States – this radically changed in the 20th century. To my surprise the radio host became very irate and angry, raising his voice saying “Iran’s nuclear program proves that they want to annihilate the West”. What was very interesting is that he was attempting to lump all of ancient Persia, the people of Iran and the current Mullah theocracy into a single monolithic. The nuclear agreement was still being negotiated at the time but far more interesting was his emotional reaction. In a sense he had to react with hostility and yelling on the radio as the information I was providing was contradicting his own belief system. Second, the radio audience was now hearing a series of facts that they had not heard before. They were learning that Iran or ancient Persia is not the “enemy” they have been taught it to be. They also learned that the regime of a country and the people and history of a country are not always one and the same. Truth can be dangerous to those who wish to suppress it.

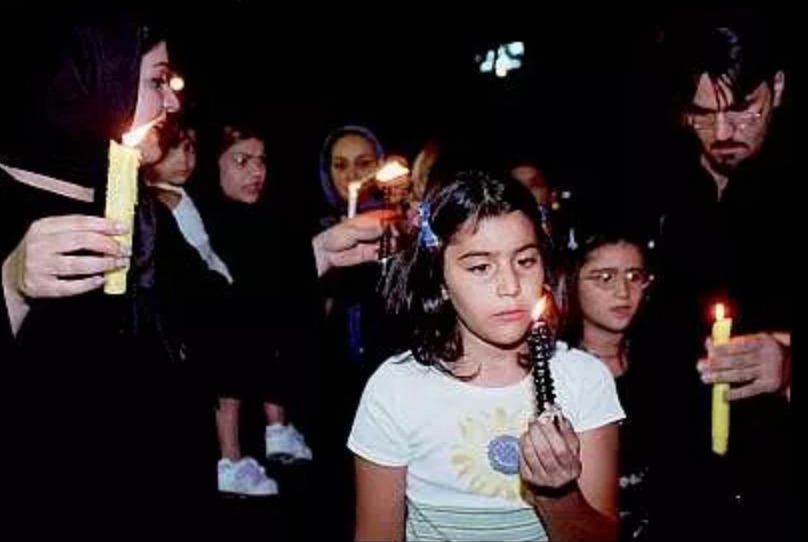

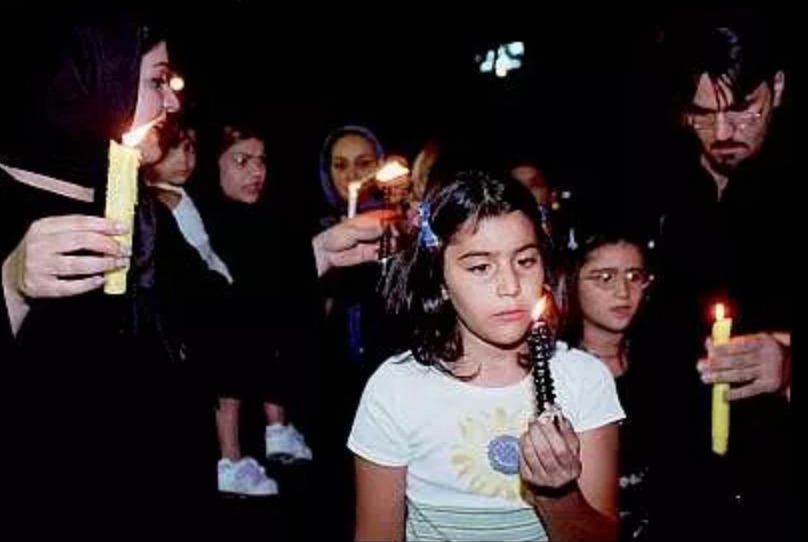

Iranians in Tehran holding a candle vigil for the victims of the September 11, 2001 attacks – Iranians were the only people in the so-called “Middle East” who held marches and vigils in solidarity with the Americans (see “The Other Iran” for more information …). However, news and images of these events have been ignored by mainstream Western outlets. The majority of the hijackers in 911 were Saudi Arabian and UAE citizens. While Iranian citizens are overwhelmingly friendly towards Western nations, citizens of Western “allies” such as Saudi Arabia and Pakistan are often not favorable to the Western world. Much like the pro-Saddam Hussein propaganda of the 1980s, Western outlets downplay “inconvenient facts” such as the above image.

There is another factor deserving mention. For decades, from the end of the First World War, there has been a steady and growing effort among certain newly established states following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, to “write out” the history and legacy of Iran in accordance with pan-Arabist views. Throughout the 20th century all the way up to today, irrespective of who has been ruling in Iran, Western governments in general have been notably silent with respect to Arab governments’ effort to fund academic programs that essentially rewrite history. Numbers of Western scholars have often protested this, but as always, geopolitics and petroleum have the last word.

Shaikh Salman Bin Hamad Al-Khalifa (at left) and Sir Charles Belgrave (right) who was England’s Government Advisor to Bahrain. It was Belgrave who first pioneered the concept of changing the name of the Persian Gulf. The motives for such revisionist schemes are not clear, but it is possible that Belgrave was calculating that such actions would create frictions between the Iranians and the Arabs.

We saw how US officials of the current Trump administration danced with Saudi Arabia’s Wahhabist leaders in May 2017, even as Trump in the 2016 election campaign had repeatedly accused Saudi Arabian complicity in much of the extremist (Wahhabist-Salfist) Sunni mayhem and terrorism. This Western tradition of courting and promoting un-elected dictators is of course nothing new.

King Abdulaziz ibn Abdul Rahman Al Saud (reigned 1932-1953) meeting with US President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945) (at right) aboard the US warship, USS Quincy, after the Yalta Conference (Feb. 4-11, 1945) (Source: Public Domain). The interpreter is Colonel Bill Eddy with Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy located to the left. Ibn Saud is on record for his racist statement “…we hate the Persians…”. Western statesmen and business lobbyists to the present day continue to ignore these types of attitudes among non-European leaders in favor of commercial and geopolitical interests.

But perhaps more dangerous in my perspective is the impact of these politics, most recently the Trump-Saudi embrace, and its potential impact on academic discourse and the invention of terminologies. Many of these newly founded (petroleum-economy) nations continue to have their historical revisionism actively promoted, especially with respect to Persephobia and erasing the legacy of Persia out of the history books. My concerns are perhaps best summarized by Salameh (2011) who astutely notes:

“Arab colonialist view of a cohesive uniform ‘Arab world,’ denuded of its pre-Arab heritage, seeps into America’s official, academic, and popular Middle Eastern discourse. Never mind that a good third of Middle Easterners are not Arab; never mind that they still use languages and partake of collective memories distinct from those of Arabs…. This is the monolithic Middle East that is being legitimized and intellectualized at America’s leading universities today; a Middle East where the millenarian ‘Persian Gulf’ is re-christened ‘Arabian,’ where a rich tapestry of culture is deemed a uniform ‘Arab world,’ and where ancient pre-Arab peoples who so much as mutter an idiom resembling ‘Arabic’ are summarily anointed ‘Arabs.” [Salameh, F. (2011, March 23). “Arabian Gulf,” and other fairytales. Gatestone Institute International Policy Council].

[11] I imagine that you have more publications pending on the subject, can you advance us on what topics they will try?

[11] I imagine that you have more publications pending on the subject, can you advance us on what topics they will try?

Affirmative, as you may imagine researchers in our domain tend to be kept busy. I plan more articles for the Persian Heritage journal and European venues, especially the ties between Europe and Greater Iran. I am also very pleased with the successful completion of the Dissertation in 2017 of Dr. Sheda Vasseghi at the University of New England where I acted as one of the academic advisors:

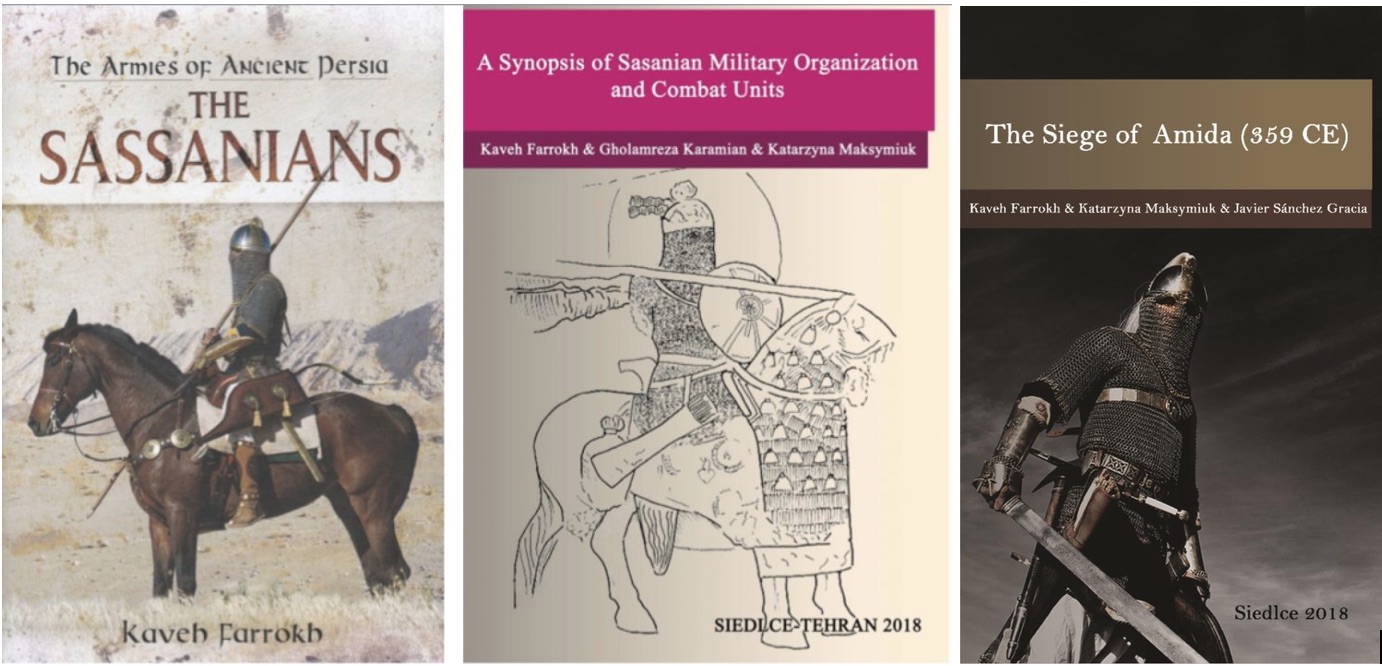

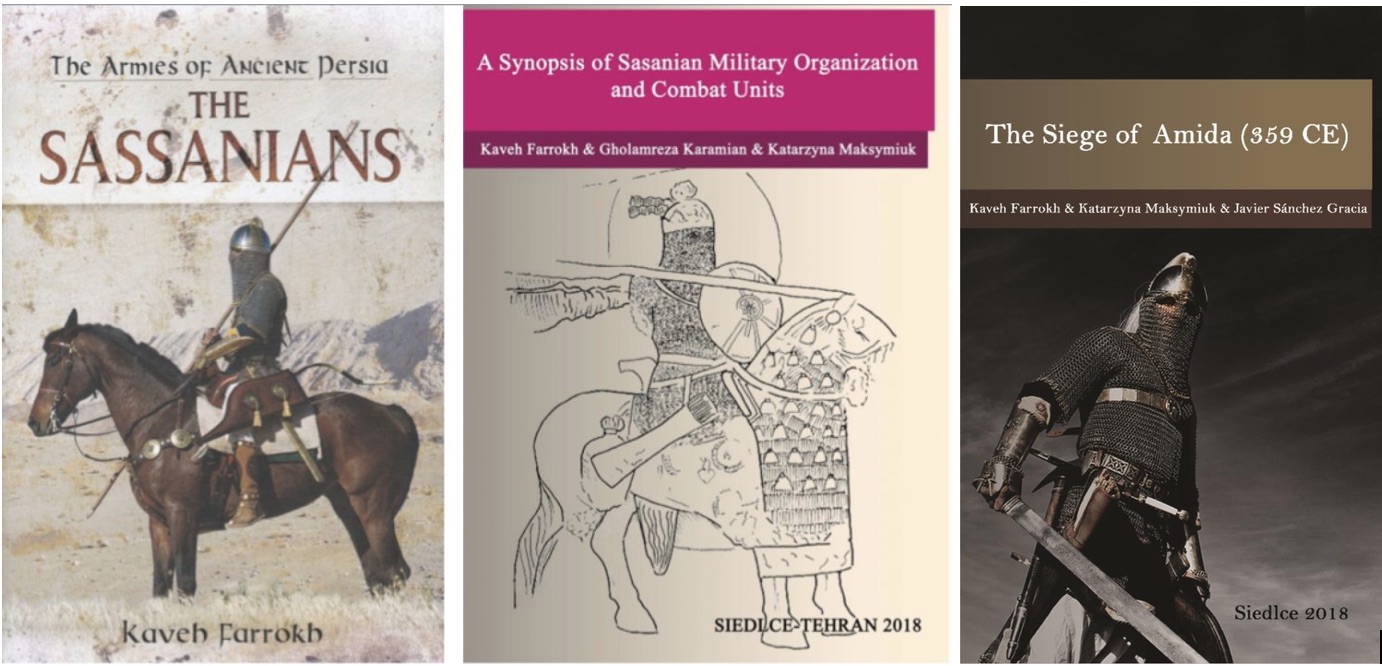

In the domain of military history, my 2017 comprehensive textbook on the Sassanian army with Pen & Sword Publishers in England was published after several production delays. As the most comprehensive textbook on the subject to date, this will provide the most detailed examination of the Sassanian army (Spah) with respect to logistics (and medical support), siege warfare and equipment, archery and close-quarter combat weapons, the Savaran cavalry (especially elite contingents), auxiliary forces (notably infantry, the elephant corps, javeliners, slingers, light cavalry, Sassanian military architecture, military operations along the Western (Romano-Byzantine) frontiers, the Caucasus, Central Asia and the Persian regions, weaknesses of the Spah (army), downfall of the Spah and subsequent anti-Caliphate resistance with the final chapter discussing the legacy of the Spah upon the Romano-Western world. This book was reviewed in 2018 by the Military History Journal. Last year in 2018, two more books on Sassanian military history were also published in collaboration with Gholamreza Karamian, Dr. Katarzyna Maksymiuk (Institute of History and International Relations, Faculty of Humanities, Siedlce University of Natural Sciences and Humanities, Poland) and of course yourself, Dr. Javier Sánchez-Gracia.

- [Left] Farrokh, K. (2017). Armies of Persia: the Sassanians. Barnsley, England: Pen & Sword Publishing.

- [Center] Kaveh Farrokh, Gholamreza Karamian, Katarzyna Maksymiuk, A Synopsis of Sasanian Military Organization and Combat Units, Siedlce-Tehran 2018.

- [Right] Kaveh Farrokh, Katarzyna Maksymiuk, Javier Sánchez Gracia, The Siege of Amida (359 CE), Siedlce 2018.

I have now begun the process of writing a comprehensive book on the Parthian military and this will be a Herculean task given the paucity of sources on this subject, however, much of this has changed, thanks in large part to the hard work of Eastern European scholars in Poland and Russia especially as well as the archaeological expeditions of my friend and colleague Dr. Reza Karamian. Karamian and I published a paper recently on two of his recent archaeological finds in Iran as well as a cursory examination of Parthian daggers and swords housed in the Iran Bastan Museum in Tehran:

Since that publication last year, many examples of new finds have been uncovered by Karamian’s team and colleagues, notably new finds of Parthian daggers, swords, armor, arrowheads and belt buckles at Vestemin in northern Persia. We published this in 2018:

Karamian and I have published other articles as well on Parthian and Sassanian militaria. The previous year also resulted in my publishing of articles on Kurdish ties to Iranian mythology as well as my article in the University of Messina’s AGON journal discussing ties between ancient Persia and Greco-Roman civilization:

Last year you and I published a very well-received article in the Persian Heritage journal entitled “The “Clash of Civilizations” paradigm and the portrayal of the “Other”:

You and I plan to write a series of articles and books on topics of Parthian and Sassanian interest, with one of our recent projects having been the Sassanian invasion of 359 CE:

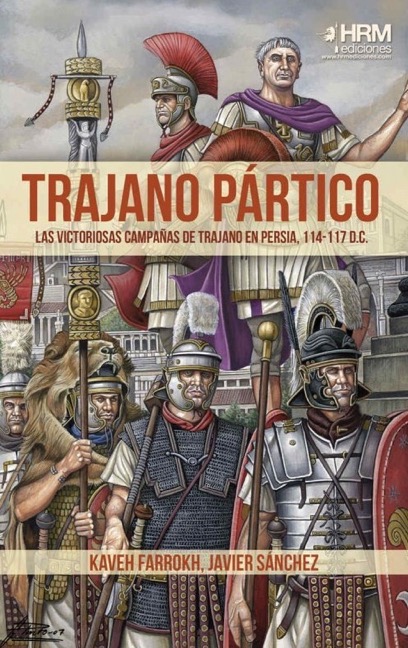

This year our book on Trajan’s campaign against the Parthian Empire was just published by HRM Ediciones:

Another article of interest was the one on the armies of the Mongols printed in a major British military history journal:

I am also working to co-author a series of new articles on the military history of Iran with Dr. Manouchehr M. Khorasani, a top specialist in the arms, armour and military lexicon of Iran. Below is an article we published in late 2018:

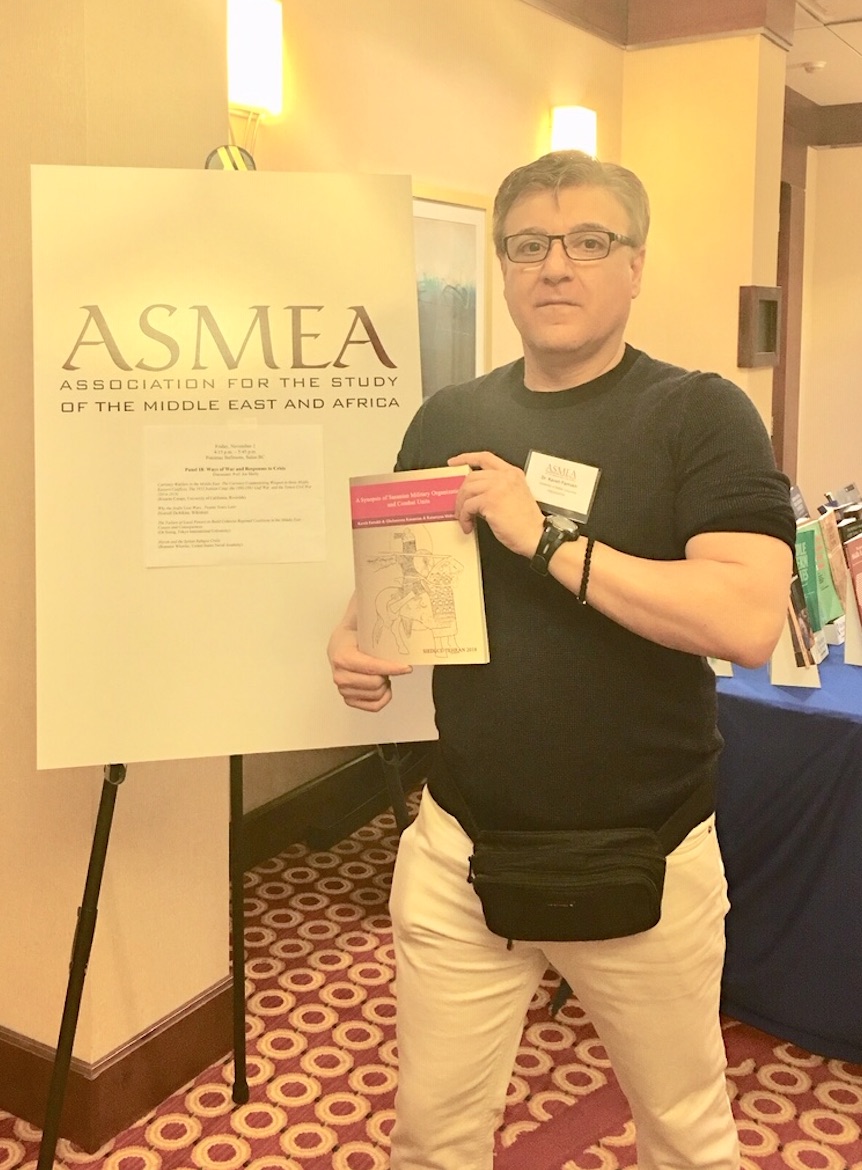

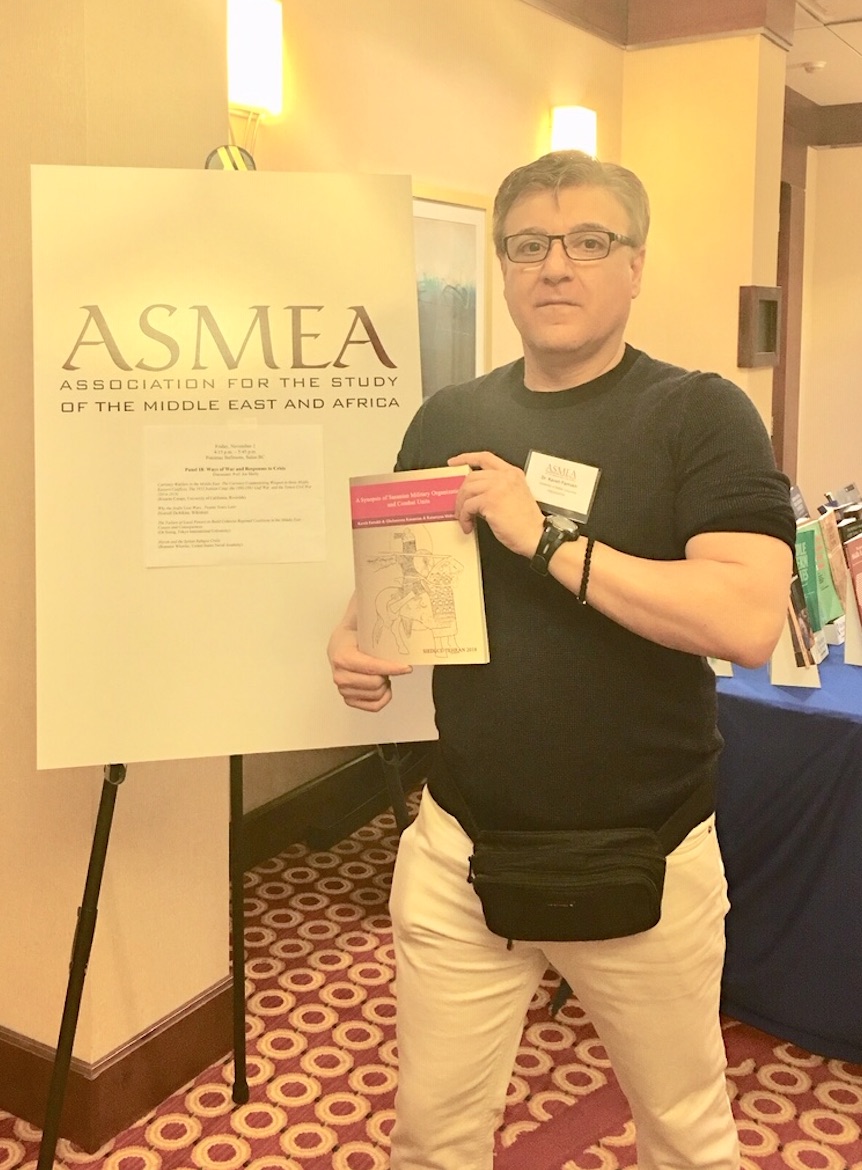

Meanwhile I have presented the following papers in the 2017 and 2018 ASMEA Conferences in held in Washington, DC:

- Farrokh, K. (2018). Parthian era Amazons? Placing the Weapons finds at Vestemin in Historical Context. The Eleventh Annual ASMEA (Association for the Study of the Middle East and Africa) Conference November 1-3, 2018, Washington DC.

- Farrokh, K. (2017). A Synopsis of Sassanian Military Organization and Combat Units. The Tenth Annual ASMEA (Association for the Study of the Middle East and Africa) Conference October 19- 21, 2017, Washington DC.

I have also published a series of articles on on more recent eras (e.g.history of the Russian air force’s operations against Iran). This year, an article by you and I on the Anglo-Soviet invasion of 1941 will appear in the Historia de Guerra journal.

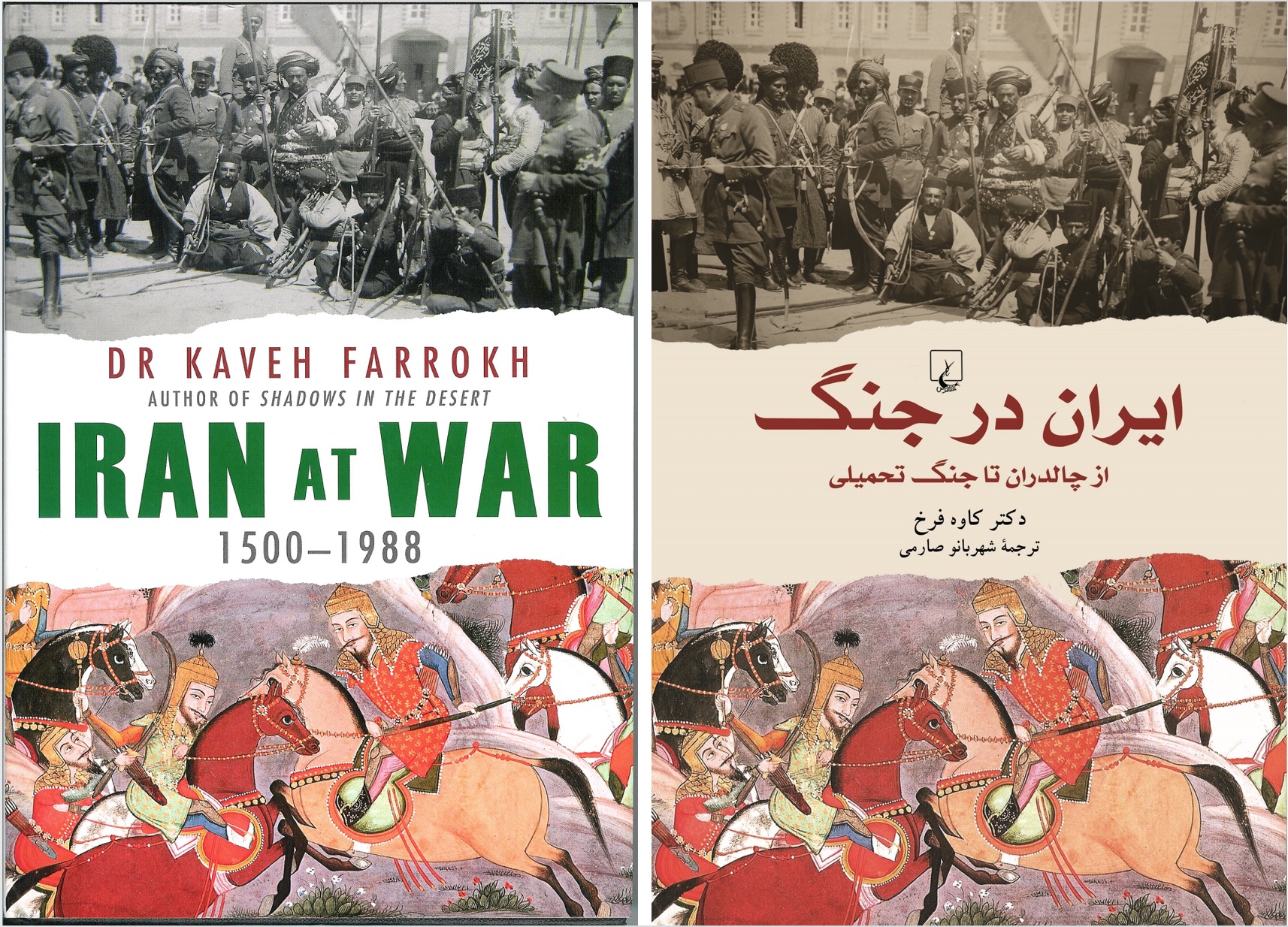

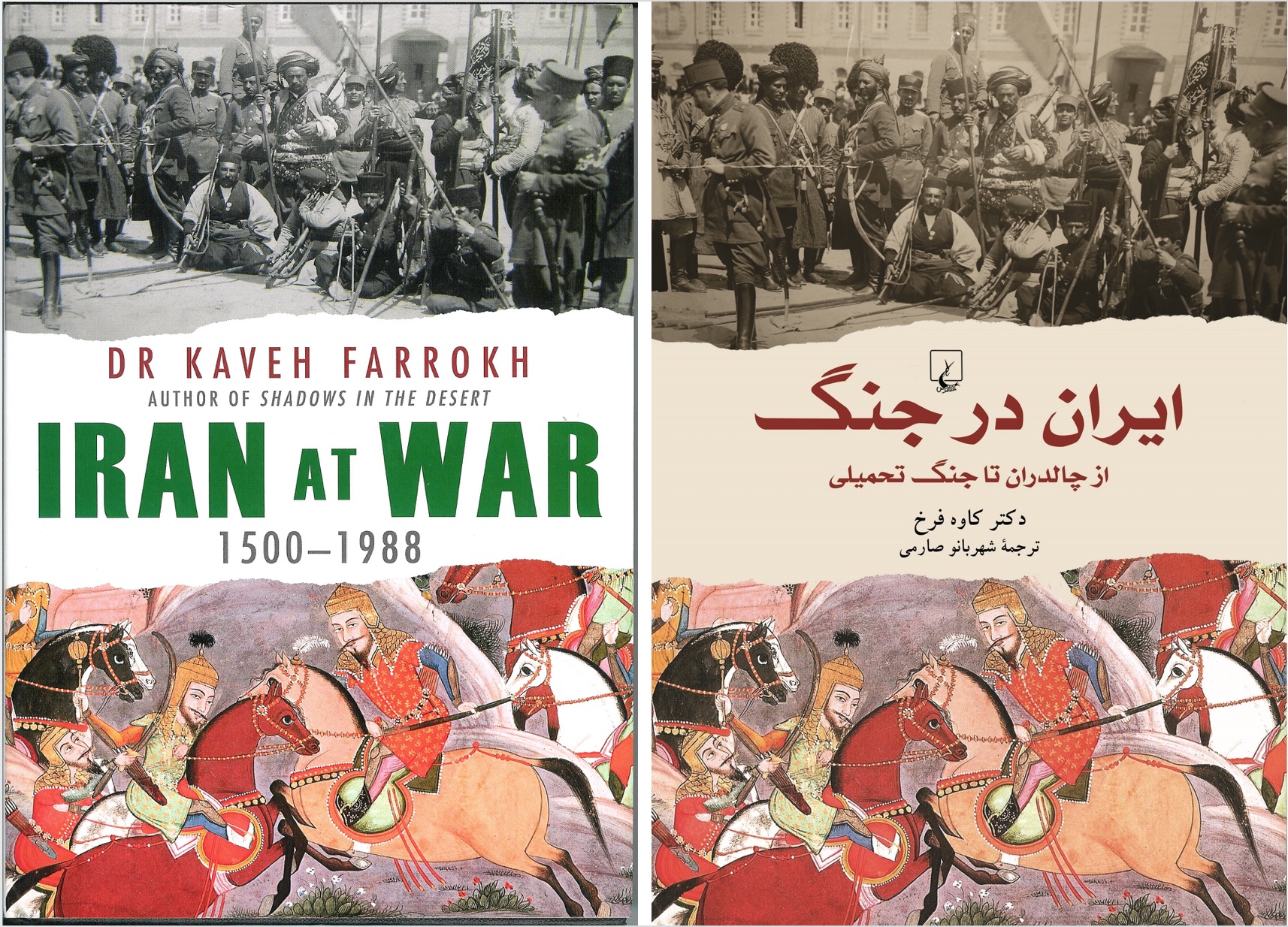

Cover pages of Iran at War (1500-1988) (Left) and the 2018 translation “ایران در جنگ” by Maryam Saremi of Qoqnoos publishers (Right). Iran at War is Farrokh’s third textbook on the military history of Iran. The total number of translations of Farrokh’s first three books are now seven. To date (Spring of 2019), Farrokh has published and co-authored eight textbooks on the Military History of Iran (two in 2018 with another in early 2019).

However given the volume of publications in general, interested readers who wish to see all my publications can consult my academia.edu profile for further information: Kaveh Farrokh-Academia.edu

[12] What is the status of humanities studies in Canada?

[12] What is the status of humanities studies in Canada?

Canada has a very vibrant, intellectually stimulating and I would say also creative academic atmosphere in general, especially with regards to the humanities. The University of Toronto has a very vibrant Iranian Studies program with a strong faculty and a series of upcoming new graduates who hold much promise. The field of military studies of ancient Iran is not large in Canada (like virtually many venues in the West at present) but the faculty we have in place are excellent. One of these is Dr. Geoffrey Greatrex at the Department of Classics and Religious Studies in the University of Ottawa.

Given that Canada has two official languages, English and French, it is also welcoming of diversity allowing for a very open academic atmosphere. This has been a powerful magnet for young academics and even professors who are coming in larger numbers to this country. Given the tense political atmosphere in the US at present along with the current Trump administration’s efforts to impose a “Muslim Ban”, in the past year we have had a numbers of Iranian graduate students arrive to Canada who initially planned to arrive to the US. This is of course a big win for Canadian academia, and I must emphasize that the migration of intellect into Canada from the US at present is not confined to Iranians but also high-achievers from many other nationalities, such as Indians for example. Our own prime minster, Justin Trudeau, is forward thinking and looks at the world in a welcoming and cooperative posture. I would dare say that this is a Canadian virtue, one that reminds me of the spirit of Cyrus the Great and the Founding fathers of the United States.

[13] Today – as always – Iran is a hot zone, will we see an East-West conflict with the Trump administration?

[13] Today – as always – Iran is a hot zone, will we see an East-West conflict with the Trump administration?