The article below has been written by Farroukh Jorat and first appeared in Fravahr.org.

=========================================================================

For a thousand years, from the Achaemenid era (VI century BC)

Mentioned in Avesta, the Vourukash sea is actually associated by some scientists with the Caspian Sea [3].

By tradition, Zoroastrian doctrine later was perceived by the Median tribe of Magi/Mugi. The name of this tribe is preserved in the name of Mugan (مغان), which is an area located east of Karabakh to the Caspian Sea coast. Starting from the early Middle Ages the word mug (مغ) has come to mean “Zoroastrian” in general.

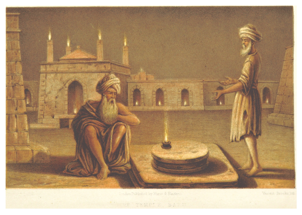

Iranian Zoroastrians in Ateshgah (Source: Farroukh Jorat); for more see Jorat’s article “The Atashgah (Fire Temple) of Baku” …

In 930, Estakhri writes in the Book of Routes and Countries that there were many villages in the Mugan, whose inhabitants were Zoroastrians [4].

It is known that when referring to Zoroastrians, Muslims used the word Gabri. The word Gabr (گبر) is preserved in the name of the south-western part of the Mugan plains, located between the Aras and Bolgarchay — (“plain of Gabrs”). There are remains of ancient fortresses Gebrbar (“Wall of Fire Worshippers”), which are located along irrigation canals — so called Gabr-arkh (“canal of Gabrs”).

Currently, there is no single point of view about the time of construction of these canals. In his book Nuzhat al-kulub, Hamdallah Mostoufi Qazwini (XIV century) writes:

Gushtasfi is the province located along the shores of the Caspian Sea and was founded by Shah Gushtasb ibn Luhrasb. He dug a great canal from the Kura River to the Aras, which diverts water from the small canals in the villages along its shores. [5]

As you can see, this area at the mouth of the Kura is called Gushtasfi, on behalf of the Shah Gushtasb, patron of Zartosht. Qazwini attributes the Gabr-arkh canals to Gushtasb.

Ateshgah and balakhani (house above the entrance) at present days (Source: Farroukh Jorat); for more see Jorat’s article “The Atashgah (Fire Temple) of Baku” …

Archaeological excavations have allowed Meshchaninov to suggest that Gabr-arkh was built in the IV-VI century, i.e., during the Sassanian times [6].

Moses of Chorene (V century) [7] and Ghevond (VIII century) [8] mentions the Bhagavan city on the Caspian coast, where eternal fires were burning and there were also fire temples. Ghevond mentions this place as Atshi-Baguan. S. Ashurbeyli believes that Atshi is a corruption of atesh (“fire”), and Ateshi-Baguan means “a place of sacred fires” [9], which implies the current city of Baku. J. Saint Martin, the French Orientalist of the early XIX century wrote:

Baku city anciently revered by Parsis […] as a sacred place because there are many sources of oil and free access of gases to the land surface, burning of natural lights. In many places, these “eternal” fires are maintained by fire-worshipers, who created a whole group of fire temples. Baku city has been transformed by their rulers and their subjects to a place of fire worshiping. [10]

To the west of Baku is located a desert area, which until the 1940’s was called Gabristan (گبرستان). In the 1940’s, after the discovery of rock paintings, this place has become famous, and the name Gabristan was deemed invalid because of its consonance with the word gabir (قبر) (“grave” in Azeri) and the district was renamed the “Gobustan”. However, as noted archaeologist Gardashkhan Aslanov, in fact stated, the name Gabristan has no relation to the word “grave” and actually means “Country of Gabris”. It is likely that this desert area was a place for Zoroastrians who were trying not to attract the attention of Muslim rulers. Now the new name Gobustan stuck and few people know the old name of the area.

The Baku Ateshgah as it appears today (Source: Farroukh Jorat); for more see Jorat’s article “The Atashgah (Fire Temple) of Baku” …

In the Gakh district of the Azerbaijan Republic, there is a mountain named Armaiti (Armatian), on top of which are the remains of a round temple dating from the V-VI century. Among the local people, it is called Peri-Gala (“Tower of the Virgin”). The name “Armatian” probably relates to Armaiti, one of the Amesha Spenta. [11]

It is known that in Zoroastrianism paradise is called Behesht or Gardman. The term “gardman” is linguistically linked to the name of the ancient province of Gardman/Girdiman known from the IV century and this area covers the territory of modern Tovuz and the Shamkir districts where there is also the village Gardmanik (Minor Gardman). The name of this province could be interpreted as “a place with a heavenly climate”. This region has long been famous for its pleasant climate and is famous as a favourite vacation spot.

In addition, there is also the river Girdiman in the Ismailli district where there are located the ruins of the Girdiman fortress built in the Sassanian time (V-VI century). The Girdiman toponym in the Ismailli district is notable in connection with the legend of Shah Key Khosrow, and existing in Lahij village is a cemetery with an old tomb engraved with “Key Khosrow” (کیخسرو).

Worshiped fire and small fires stand in line in the background cells (1865) (Source: Farroukh Jorat); for more see Jorat’s article “The Atashgah (Fire Temple) of Baku” …

According to Zoroastrian tradition, Key Khosrow reigned for sixty years, after which with his soldiers he migrated to the mountains. There, the Shah mysteriously disappeared, and his soldiers were killed during a blizzard. According to the legend, Khosrow was lifted up to heaven (Gardman) by Ormuzd. The Lahiji people believe that Key Khosrow made his last campaign in Shirvan, and then he disappeared in the Girdiman province. Probably the basis of this legend was the reason for the construction activity in Shirvan by Shah Khosrow Anushirvan (531-579), whose legendary image combines the features of the mysteriously disappeared Key Khosrow. In addition, the Lahij village is remarkable in that its people speak a language very close to Persian.

Toponyms of Zoroastrian character are found not only on land but at sea as well. Sangi Mugan and Stone of Ignatius are two close-lying uninhabited islands off the west coast of the Caspian Sea, situated about 60 km south of Baku Bay and 20 km north-east of Cape Bandovan. The islands are not more than 1 km in length and 1 km wide, with sparse vegetation and their two craters of mud volcano are surrounded by shoals.

The name of the Sangi Mugan island (سنگ مغان) means “Stone of Magi” in Persian. The name of the neighbouring island (Stone of Ignatius) is a carbon copy (Ignatius derived from Latin Ignis, “Fire”, i. e. Stone of Fire).

The connection of the islands of the Caspian Sea with the Zoroastrian religion is indirectly indicated by Hamdallah Qazwini who wrote:

About […] the islands of the [Caspian] sea is told in the treatises on cosmogony.

The only cosmogonic treatise, which allegedly mentioned the Caspian Sea, is a Zoroastrian text called Bundahishn.

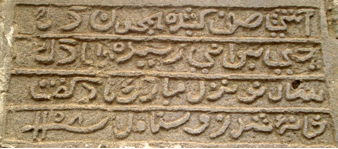

Persian (Zoroastrian) inscription in Ateshgah (Source: Farroukh Jorat); for more see Jorat’s article “The Atashgah (Fire Temple) of Baku” …

Footnotes

[1] KROLL Stephan: “Medes and Persians in Transcaucasia: archaeological horizons in north-western Iran and Transcaucasia”, in G. B. Lanfranchi, M. Roaf, R. Rollinger, eds., Continuity of Empire (?) Assyria, Media, Persia. Padova, S.a.r.g.o.n. Editrice e Libreria, 2003, pp. 281-287. [2] DASXURANCI Movses: The History of the Caucasian Albanians, transl. by C.J.F. Dowsett, London, 1961. [3] BRUNNHOFER H.: Arische Urzeit. Bern, 1910, pp. 39-42. [4] آذری یا زبان باستان آذربایجان: احمد کسروی. [5] نزهه القلوب حمدالله مستوفی. [6] Мещанинов И. И. Краткий осведомительный отчет о работе Мильской экспедиции 1933 года. Труды Аз. ФАН СССР, 1936, т. XXV-Баку: Аз ФАН СССР, с. 5-31. [7] Moses of Chorene: The History of Armenia. [8] Histoire des guerres et des conquêtes des Arabes en Arménie, par l’éminent Ghevond, vardabet arménien, écrivain du huitième siècle. [9] С. Б. Ашурбейли. Очерк истории средневекового Баку (VIII – нач.XIX в.в.), Издательство АН Азерб.ССР, Баку 1964. 336 стр.(21 п.л.). [10] SAINT-MARTIN M. J.: Mémoires historiques et géographiques sur l’Arménie I, Paris, 1818, p. 153-154. [11] Карахмедова Л. А. Христианские памятники Кавказской Албании (Алазанская долина). Баку, 1986.,16-17.