The article “Indo-Iranian” published in the Indo-European Info venue is originally an academic paper, which is cited as follows:

- Quiles, Carlos (2017). Indo-European demic diffusion model (3rd ed.). Badajoz, Spain: Universidad de Extremadura.

- DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.31997.67040

This project is part of Academia Prisca‘s Indo-European Network.

===================================================================

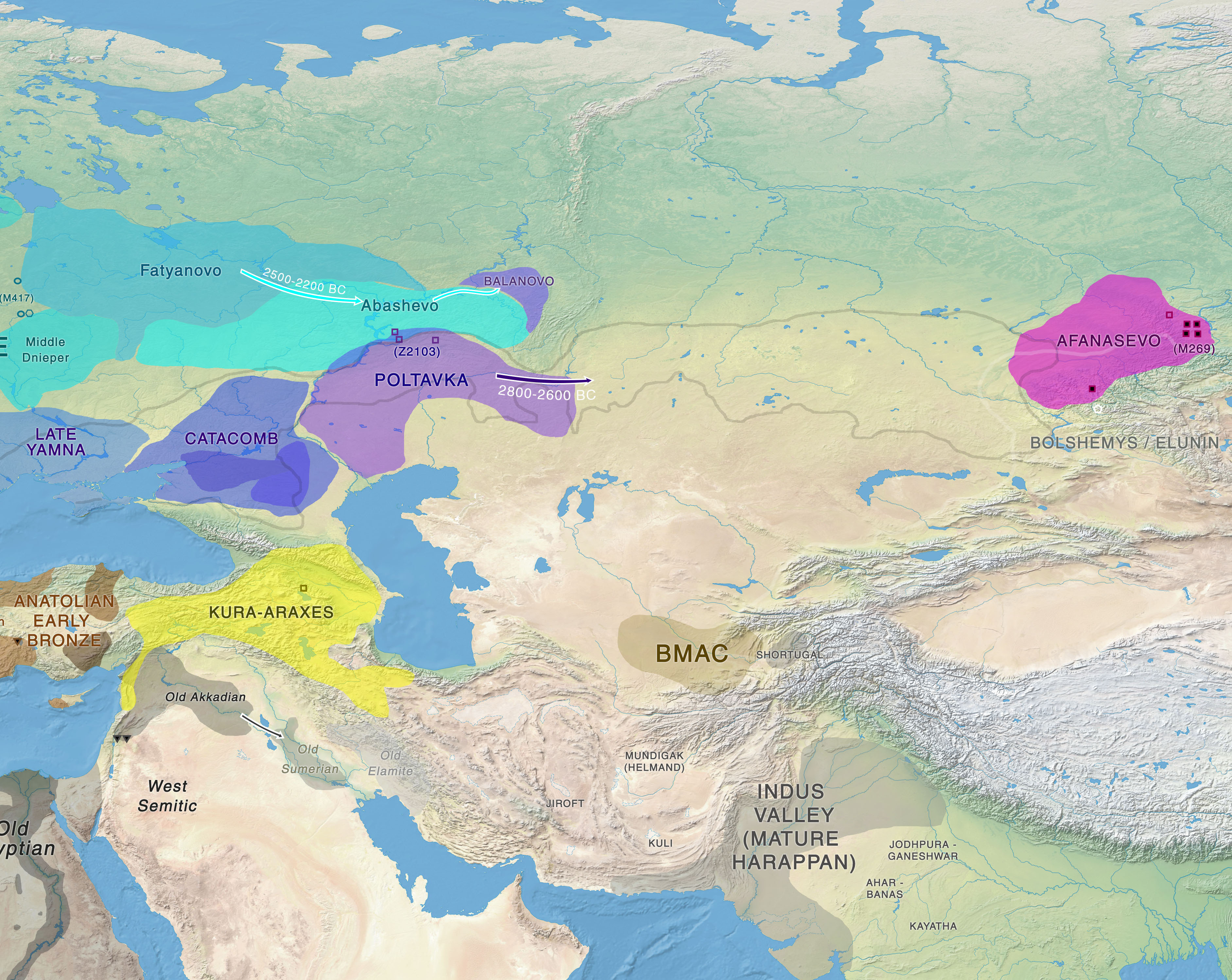

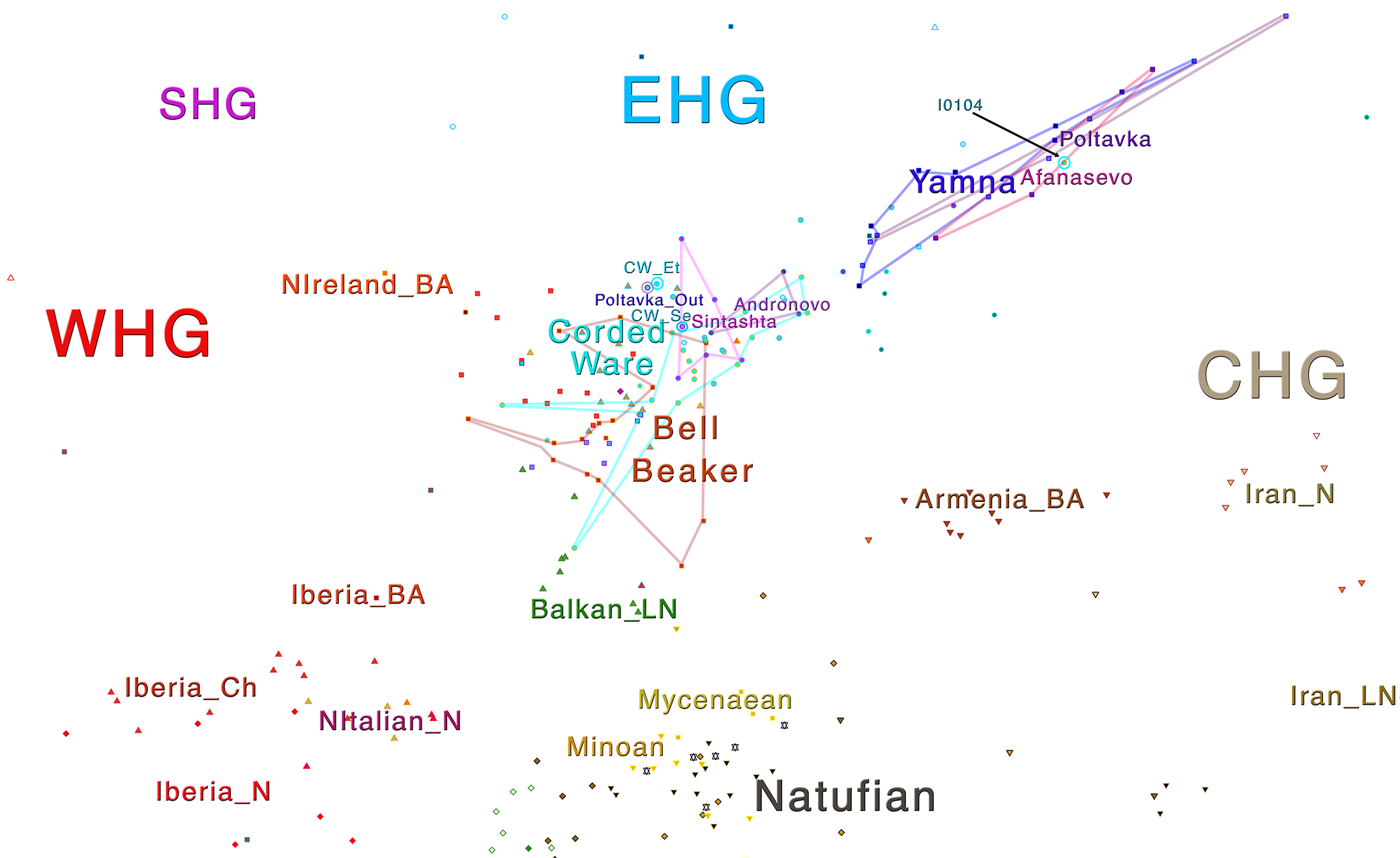

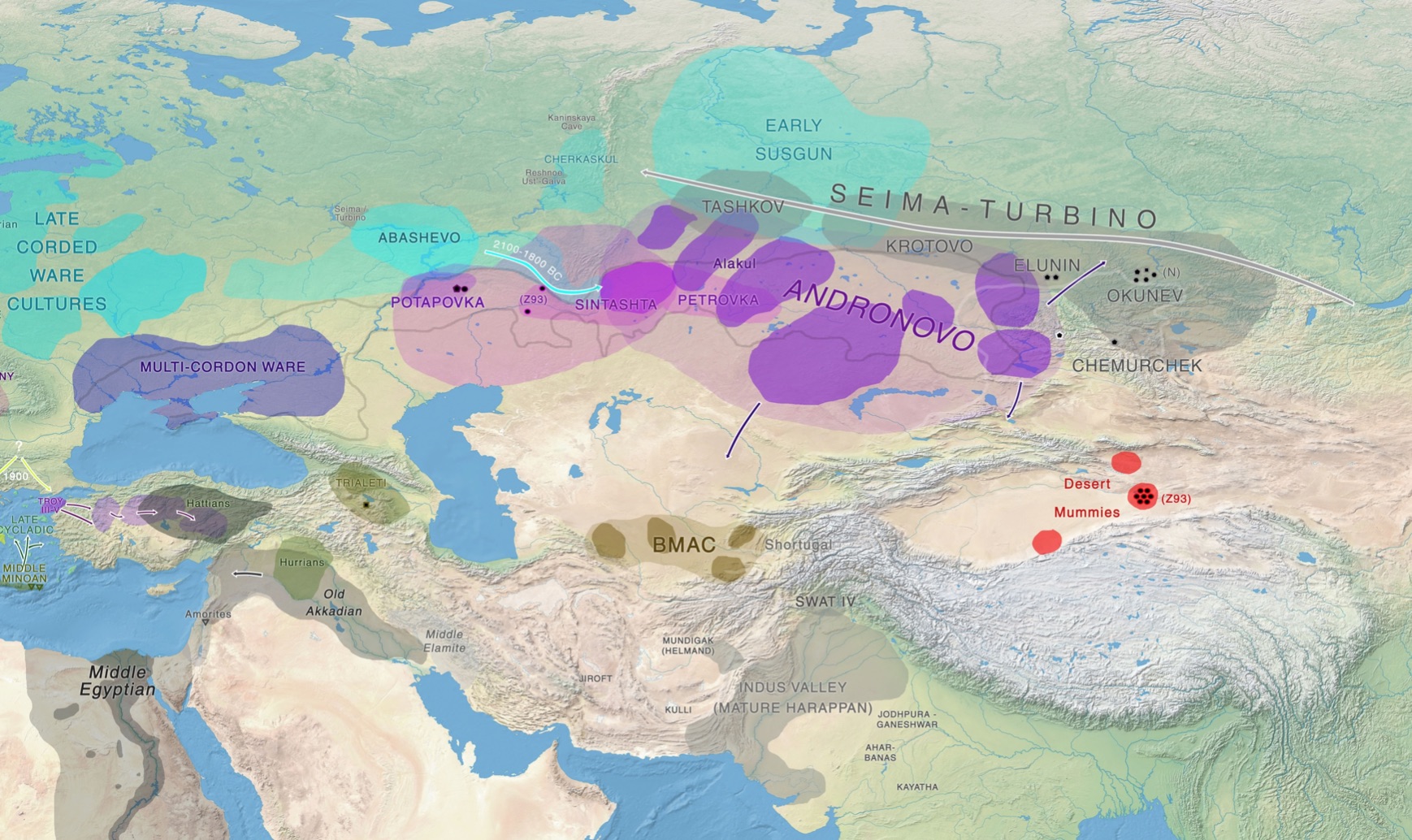

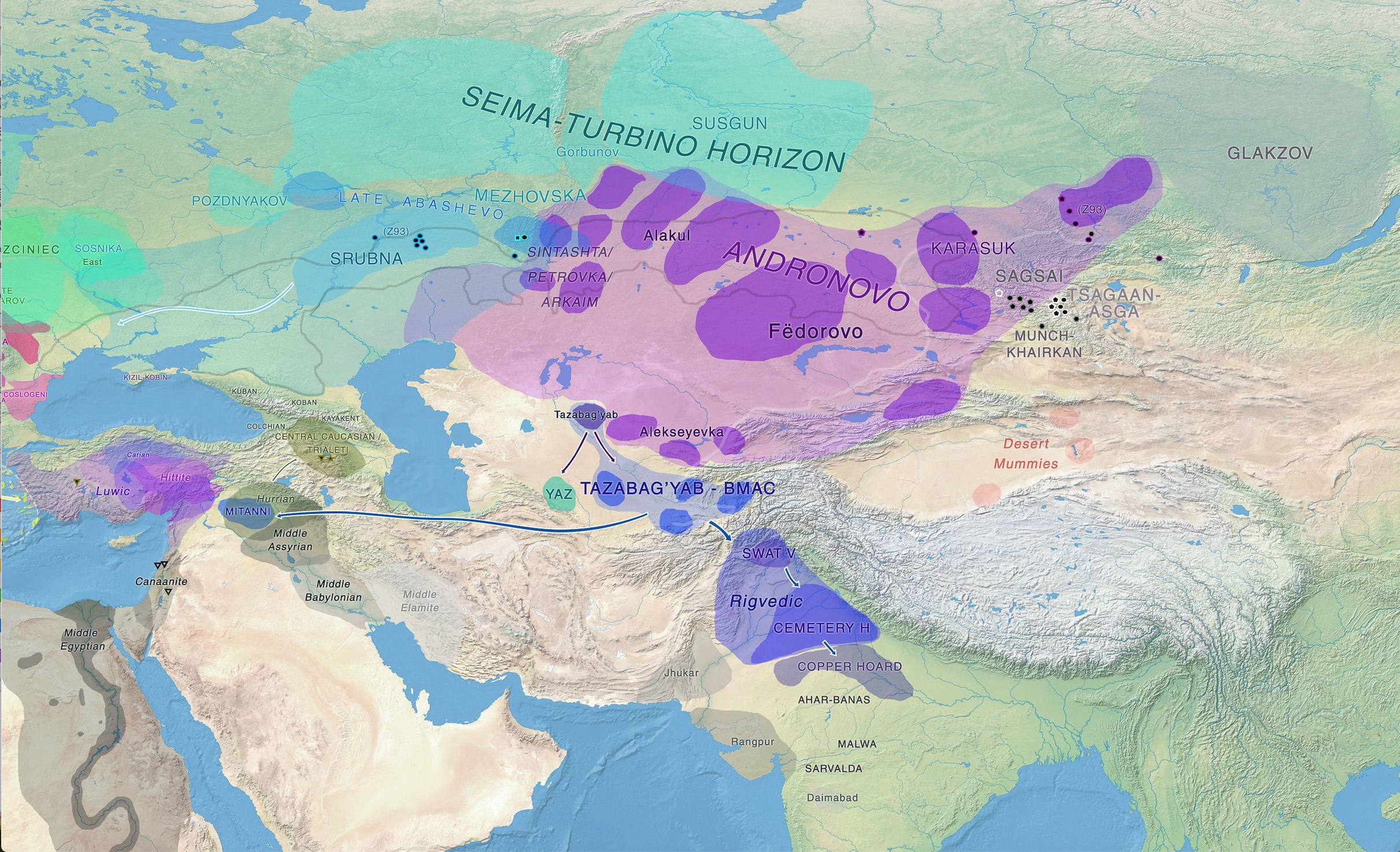

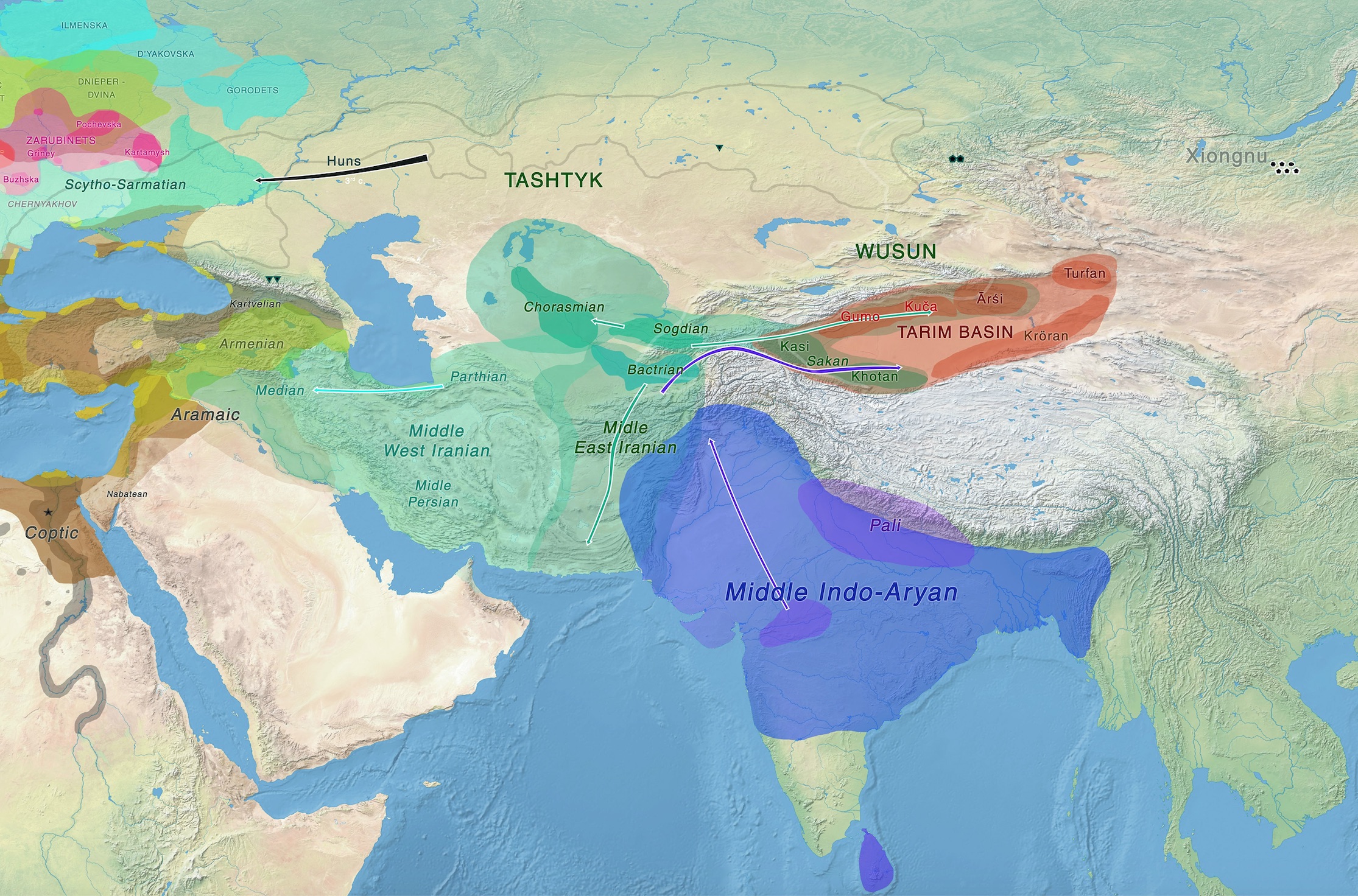

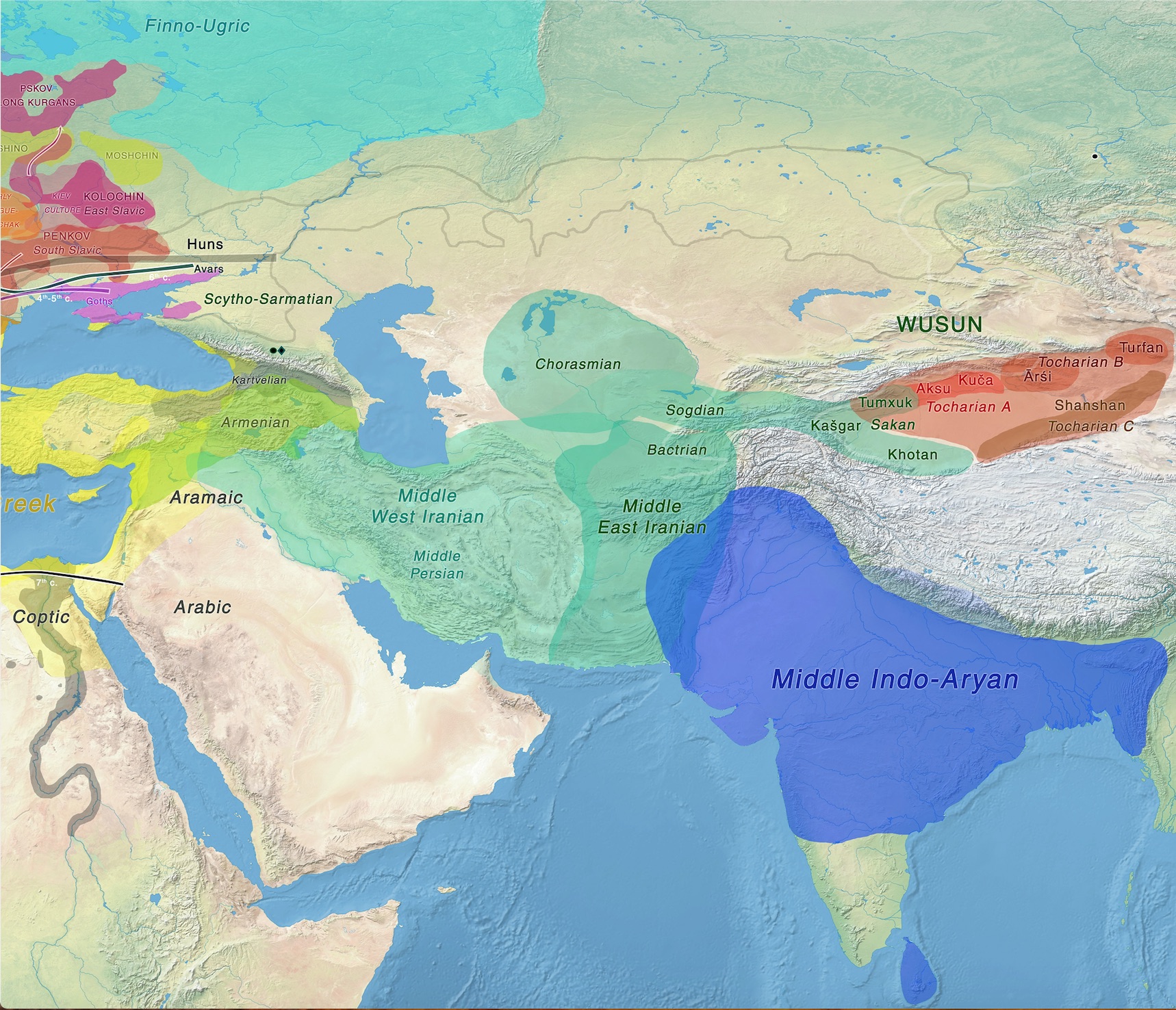

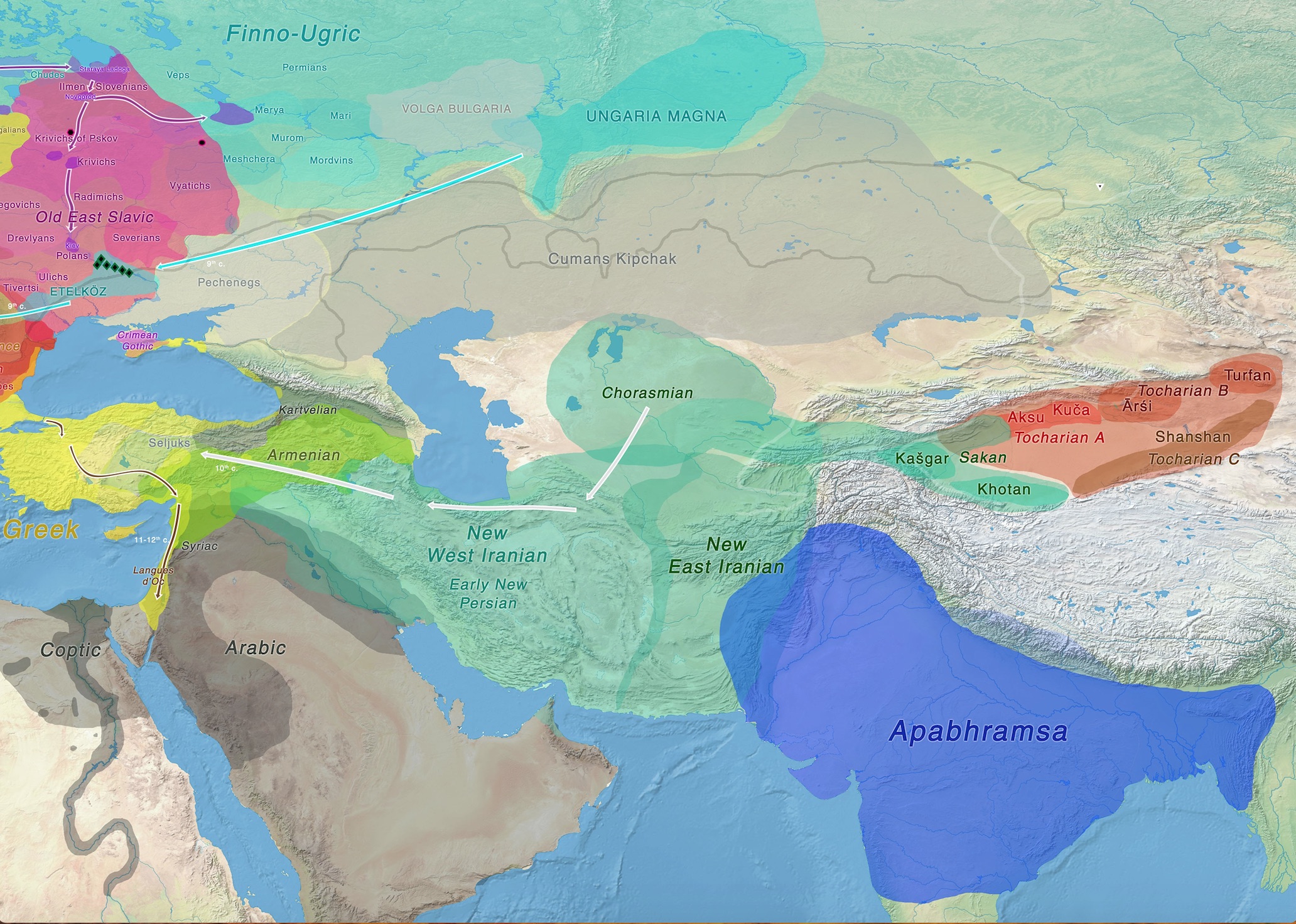

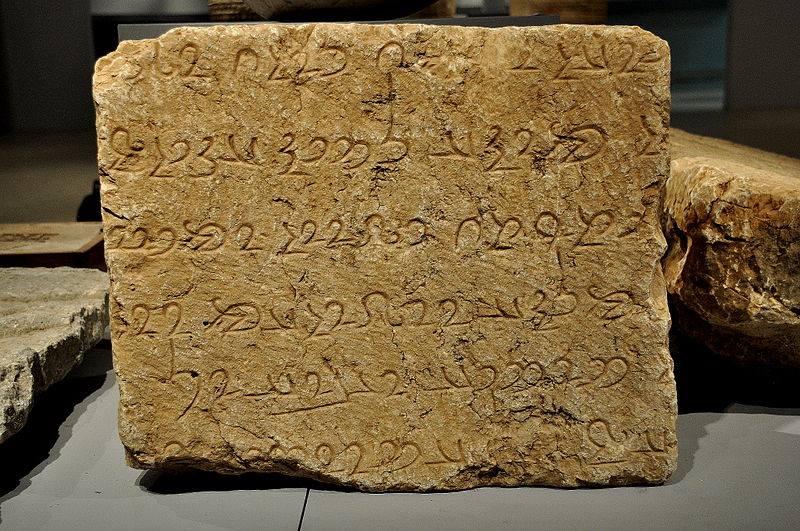

During the western expansion of Yamna herders in the Bronze Age, the Fatyanovo group emerged early at the north-eastern edge of the Middle Dnieper group, still showing mixed Corded Ware / Globular Amphora traits, substituting the Volosovo culture and occupying the Volga-Kama region. Near it the Balanovo group seems to have been its metallurgical heartland In the forest-steppe zone of the middle Volga and upper Don, at the easternmost aspect of the Russian forest-zone, the last cultures descended from Corded Ware ceramic tradition, the Abashevo group, emerged ca. 2500 BC or later[Anthony 2007], substituting the late Volosovo culture, and reaching the Upper Ural basin. Abashevo showed a mix of Fatyanovo/Balanovo and Catacomb/Poltavka culture. Genetic make-up of modern populations show a distribution of basal R1a1a1b1a-Z282* lineages centred on the old territory of Middle-Dnieper – Fatyanovo – Abashevo groups[Underhill et al. 2015], and a sample of haplogroup R1a1a1b-Z645 is found later in the Potapovka culture, in Utyevka ca. 2200-1900 BC[Mathieson et al. 2015]. Early Yamna continued in the Lower Don – North Caucasian steppe as the Catacomb culture, and in the Volga-Ural region as the Poltavka culture, where human ancestry and cultural continuity implies that eastern languages from the Graeco-Aryan continuum – already separated from the western Paleo-Balkan group – were spoken, i.e. the ancestor of Proto-Indo-Iranian. Herders from the Poltavka culture began to move to the Ural-Tobol steppes probably about 2800-2600 BC. Coinciding with more arid climate after ca. 2500 BC, both Poltavka and Abashevo herders settled between the Tobol and Ural River valleys. The Poltavka outlier of R1a1a1b2-Z93 lineage found in Potapovka, in the Samara region, dated ca. 2710 BC[Mathieson et al. 2015], clusters closely with samples from the Corded Ware and from later Sintashta, Andronovo, or Srubna cultures. Unlike other samples of R1b1a1a2a2-Z2103 lineage found in the same area, this grave was most likely established on top of an older Poltavka cemetery in the Middle Bronze Age, where a Sintashta culture cemetery was later found[Mathieson et al. 2015]. The early date, only slightly later to its haplogroup formation, points to a period of population expansion, and probably also to intense early regional contacts between peoples of Abashevo and Poltavka cultures. Diachronic map of Copper Age migrations in Asia ca. 3100-2600 BC [Anthony 2007][Harrison and Heyd 2007][Sjogren, Price, and Kristiansen 2016][Heyd 2012][Heyd 2014].(Source: Indo-European Info). Cultures that emerged around 2100-1800 BC in the region – Sintashta in the Ural-Tobol steppes, and Potapovka in previous Poltavka territory – seemed to continue in an early phase the previous Abashevo tradition, but retained and gradually expanded many cultural traits of Poltavka pottery, followed the same burial rites, and settled on top of or incorporated older Poltavka settlements. “It is difficult to imagine that this was accidental. A symbolic connection with old Poltavka clans must have guided these choices”[Anthony 2007]. Warring groups were strong enough to take and destroy an entire settlement, signalling an age of fully-fledged conflict, with a succession of changes in the defence systems and planning schemes of the settlements. Both Sintashta and Potapovka were born from a time of escalating conflict and competition between rival tribal groups in the northern steppes, where raiding must have been endemic, and intensified fighting led to the invention of the light chariot[Anthony 2007]. The state of intense warfare was caused by a constant flow of wealth, originating from long-distance metal trade, with formation and destruction of alliances and gathering of large groups of warriors, which created a vicious circle of escalation of conflict, and created new customs, new tactics, and new weapons[Pinheiro 2011]. Diachronic map of Copper Age migrations in Asia ca. 3100-2600 BC[Anthony 2007][Harrison and Heyd 2007][Sjogren, Price, and Kristiansen 2016] [Heyd, 2007][Heyd 2012](Source: Indo-European Info). Ancient DNA samples of Sintashta and Potapovka show a substitution of R1b1a1a2a2-Z2103 lineages by R1a1a1b-Z645 lineages[Allentoft et al. 2015], but while Sintashta samples cluster closely to other Corded Ware samples, Potapovka samples cluster closer to steppe than any other culture related to Corded Ware, which points to a different process of expansion for both. Cultural continuity of both cultures with Poltavka is not only seen archaeologically in material and symbolic culture, but is also evident from the association of the Sintashta expansion with Andronovo (both clustering closely together), and therefore with the later expansion of Indo-Iranian peoples and their languages. The most likely explanation for the eastern expansion of Indo-Iranian by peoples with R1a1a1b2-Z93 lineage is therefore the assimilation by Sintashta-Petrovka groups of the Proto-Indo-Iranian language spoken by Poltavka herders. Detail of PCA analysis of free datasets including Minoans and Mycenaeans[Lazaridis et al. 2017], and Scythian and Sarmatian[Unterländer et al. 2017] samples. PC2 vs. PC1. The graphic has been arranged so that ancestries and samples are located in geographically friendly axes similar to north-south (Y), east-west(X). Symbols are used, in a simplified manner, in accordance with symbols for Y-DNA haplogroups used in the maps. Labels have been used for simplification. Areas are drawn surrounding Yamna/Poltavka, Corded Ware (including samples from Estonia, Battle Axe, and Poltavka outlier), and succeeding Sintashta and Andronovo cultures, as well as Bell Beaker. Corded Ware sample I0104, from Erperstedt, has also been labelled. The process by which this cultural assimilation happened in the Sintashta-Petrovka region, given the presupposed warring nature of their contacts, remains unclear. It is conceivable, in a region of highly fortified settlements, to think about alliances of different groups against each other, akin to the situation found in Bronze Age Europe: a minority of Abashevo chiefs and their families would dominate over certain fortified settlements and wage war against other, neighbouring tribes. After a certain number of generations, the most successful settlements would have replaced the paternal lineages of the region – with only a slight drift to steppe admixture observed in PCA compared to Corded Ware –, while the majority of the population in these settlements – including females, commoners and slaves – retained the original Poltavka culture. R1b1a1a2a2-Z2103 lineages were mostly replaced in the region by haplogroup R1a1a1b2-Z93, as demonstrated by the later expansion of its subclades with Andronovo and Srubna cultures, and by present-day distribution of R1a1a1b2-Z93 lineages in Eurasia. The language spoken by peoples of the Srubna (“Timber Grave”) culture of ca. 1800-1200 BC – heirs of the Pokrovka complex (ca. 1900-1750 BC) created by Potapovka and late Abashevo groups – was probably an Indo-European language of the Graeco-Aryan group. Their repeated violation of the canid-eating taboo across generations point to the connection of dogs with war-bands and with the Indo-European myth of dogs guarding the entrance to the afterlife[Anthony and Brown 2017]. Diachronic map of migrations in Asia ca. 2250-1750 BC [Anthony 2007][Krause 2013][Hanks, Epimakhov, and Renfrew 2015][Jaeger 2012][Kristiansen and Larsson 2005][Fokkens and Harding 2013][Meller et al. 2015](Source: Indo-European Info). A paleoecological crisis had a significant effect on the economy of the tribes in Late Catacomb and Post-Catacomb times, favouring a higher mobility and transition to nomadic cattle breeding[Demkina et al. 2017]. This crisis might have allowed for the westward expansion of eastern R1a1a1b2-Z93 lineages associated with the Srubna culture, which replaced the Catacomb culture in the Pontic-Caspian steppe. Continuity of the Potapovka population explains the elevated steppe component found in this culture, compared to Sintashta and other cultures derived from the Corded Ware complex. Samples from the Balkans during the Middle Bronze Age (later than ca. 1700 BC) show an increase in steppe ancestry compared to earlier samples from the Balkans[Mathieson et al. 2017]. Together with the finding of an individual of elevated steppe ancestry and haplogroup R1a1a1b2-Z93 in the Balkans, this further supports that the westward expansion of the Srubna culture from the North Caspian steppe was associated with an homogenisation of steppe lineages to R1a1a1b2-Z93 subclades. Later Cimmerian or Thraco-Cimmerian groups might have emerged from societies related to these expanding western groups of Pontic-Caspian herders, who might have further increased steppe ancestry in the Balkans. Their relationship to Scytho-Sarmatian groups later migrated from south Asia is unclear. A comprehensive description of Sintashta-Petrovka expansion eastward as part of the Andronovo horizon in Asia – coinciding with the western expansion of the Seima-Turbino phenomenon to the Forest Zone – is given by Anthony[Anthony 2007]. Chariots were probably invented in the steppes, improving warfare and likely playing a big role in Indo-Iranian expansion within the Andronovo horizon (after ca. 1900 BC) and south from the Zeravshan valley into the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (after ca. 1800 BC), creating between 1800-1600 BC a post-BMAC culture dominated by Tazabagyab-Andronovo herders. The drift toward steppe ancestry found in Andronovo samples point to an admixture with a previous population from the steppe, potentially related to east Yamna and Afanasevo migrants in the area. In the Murghab region, a change is seen in access to water – essential for life in the region – in the transition from the Late Bronze Age to the Iron Age (Yaz I), evidence of a political-economic system that was shifting toward territorial management. This period is characterised by a combination of sand encroachment from the north, shifts in known watercourses and a possible decrease in flows, as well as the invasion of people represented by ‘steppe’ pottery, with declines and abandonment of major population centres[Rouse and Cerasetti 2016]. After about 1600 BC pastoral economies spread across Iran and into Baluchistan, and ca. 1500 BC Indo-Aryan chariot warriors invaded a Hurrian-speaking kingdom of Mitanni in north Syria. At the same time, as post-BMAC herders spread to the northeast Indian subcontinent, the Rig Veda was probably being composed. Diachronic map of migrations in Asia ca. 1750-1250 BC [Anthony 2007][Kristiansen 2016][Kristiansen 2014][Fokkens and Harding 2013][Wels-Weyrauch 2011][Przybyła 2009][Makarowicz 2009]. Diachronic map of migrations in Asia ca. 1250-750 BC[Butler, Arnoldussen, and Steegstra 2011/2012][Wels-Weyrauch 2011][Kristiansen 2000][Przybyła 2009]. Diachronic map of migrations in Asia ca. 750-250 BC[Thurston 2009][Cunliffe and Koch 2012]. Diachronic map of migrations in Asia ca. 250 BC – 250 AD. Diachronic map of migrations in Asia ca. 250-750 AD. Diachronic map of migrations in Asia ca. 750 – 1300 AD. The modern distribution of R1a1a1b2-Z93 lineages shows a clear division between western and eastern subclades – with basal R1a1a1b2-Z93 located east of the Andronovo horizon[Underhill et al. 2015]. Whereas the western R1a1a1b2a1-L657.1 subclade has an expected peak in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent – broadly coincident with the spread of Proto-Indo-Aryan and Indo-Aryan languages –, the eastern R1a1a1b2a2-Z2124 subclade peaks at the core of the Proto-Iranian Yaz culture and East Iranian expansion (of languages related to old Bactrians, Sogdians, and Scytho-Sarmatian peoples). Its spread west of the Iranian Plateau, however, is complicated by this region’s condition of place of transit of innumerable cultures and peoples in prehistoric and historic times – as is the case with the genetic make-up of southern Italian and Balkan peninsulas. References