The article below is written by Antonio Panaino and originally posted in the CAIS website hosted by Shapour Suren-Pahlav in London, England. Readers are also encouraged to consult/click the link “The Sassanian Era” (or click image below …)

=======================================================================

=======================================================================

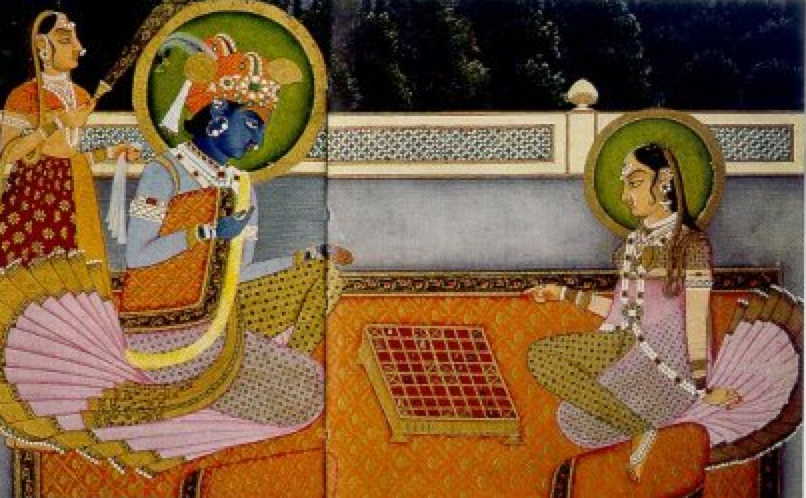

Name of a game from the Sassanian era which has not been precisely identified. The haštpay “eight feet” (more likely than aštapad) is mentioned together with other games in chapter 15 of the Xusraw ud Redag (ud pad Chatrang ud new-ardaxšî r ud haštpay kardan az hamahlan fraztar hom “and in playing chess, backgammon and the haštpay I am superior to my comrades” (Unvala, p. 16; Monchi-Zadeh, 1982, p. 65; Panaino, 1999, p. 51). Its name, as in the case of chess (Pahl. Ch < Skt. caturanµga-), is an Indian borrowing; it derives from Sanskrit astapada- (cf. pali atthapada), originally referring to a game-board of 8 x 8 little squares. Such a board was used for various games (Murray, 1913, pp. 35-40; 1952, pp. 129-36), one of them played, according to the Balabharata (II, 5, pp. 10-13), with red and white pieces and a pair of dice. In many other sources the astapada- was doubtless the chessboard and its name strictly associated with this game (MacDonell, p. 122; Jacobi, p. 228; Thomas, 1898, pp. 272; 1899, pp. 365; Thieme, 1984, p. 208).

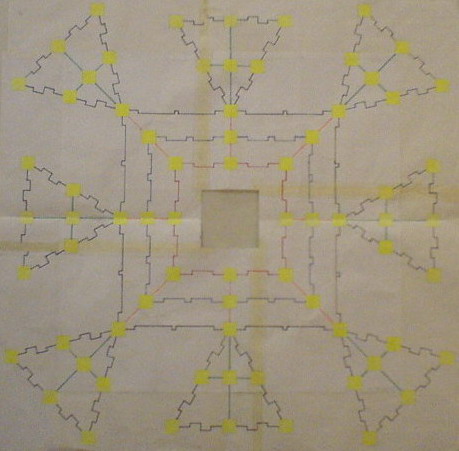

A conjectural drawing by Ashkan H. () of a possible configuration of the Hashtpay game-board (Source: Public Domain).

From the Xusraw ud Redag it is clear that the Sassanian haštpay was distinguished from other popular games like chess and the variety of backgammon represented by new-ardaxšî r. The haštpay could perhaps be associated, according to Semenov (pp. 16-20, 131; but see Panaino, 1999, pp. 153-56, 189), with a game-board (with three lines of eight squares) recently discovered in Paikend and with another one represented on a later Sassanian silver cup with a different but apparently comparable form.

An Indian manuscript depicting Krishna and Radha playing chaturanga on an 8×8 Ashtāpada (Source: CAIS). For more see “Chess: An Indian or Iranian invention” …

Bibliography

Jacobi, “Über zwei ältere Erwähn-ungen des Schachspiels in der Sanskrit-Litteratur,” ZDMG 50, 1896, pp. 227-33.

A. MacDonell, “The Origin and Early History of Chess,” JRAS, 1898, pp. 117-41.

Monchi-Zadeh, “Xus-rôv i Kavâtân ut Rêtak,” in Monumentum Georg Morgenstierne, vol. II. Acta Iranica 22, Leiden, 1982, pp. 47-91.

J. R. Murray, A History of Chess, Oxford 1913. Idem, A History of Board-Games other than Chess, Oxford 1952.Panaino, La novella degli Scacchi e della Tavola Reale. Un’antica fonte orientale sui due gixochi da tavoliere piuà diffusi nel mondo euroasiatico tra Tardoantico e Medioevo e sulla loro simbologia militare e astrale. Testo pahlavi, traduzione e commento al Wiz-arišn î Chatrang ud nihišn î new-ardaxšî r “La spiegazione degli scacchi e la disposizione della tavola reale,” Milano, 1999.

L. Semenov, Studien zur sogdischen Kultur an der Seidenstrasse, Wiesbaden, 1996.

Thieme, “Chess and Backgammon (Tric-Trac) in Sanskrit Literature,” in E. Bender, Indological Studies in Honor of W. Norman Brown, New Haven, 1962, pp. 204-16, reprinted in Kleine Schriften, Wiesbaden, 1984, pp. 413-25.

W. Thomas, “The Indian Game of Chess,” ZDMG, 52, 1898, pp. 271-72; 53, 1899, pp. 364-65.

M. Unvala, The Pahlavi Text “King Husrav and his Boy,” published with its Transcription, translation and copious notes, Paris, n.d.[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]