Mani was born in 216 CE near Ctesiphon (capital of the Sassanian Empire) either in the town of Abrumya or Mardinu in the Babylonian district of Nahr Kutha. He was of Iranian Parthian origin, with his father Patik (Babak?) hailing originally from Hamedan before moving to the Mesopotamian plains. Mani’s mother Mariam may have been of the Kamsakaran Parthian clan of Armenia (see for example the Chinese Compendium, Henning, 1943, p.52; reprinted 1977, II, p.115).

A portrait of the prophet Mani (216-274 or 277 CE) (Source: Great Thoughts Treasury). Mani viewed himself as the final seal of the prophets, completing the previous religious messages of Zoroaster, Christ and the Buddha. His theological views, especially with respect to evil and its relation to material existence incurred the wrath of not only the Zoroastrian Magi of his Persian homeland but also that of the later Christians and Emperors of China.

A portrait of the prophet Mani (216-274 or 277 CE) (Source: Great Thoughts Treasury). Mani viewed himself as the final seal of the prophets, completing the previous religious messages of Zoroaster, Christ and the Buddha. His theological views, especially with respect to evil and its relation to material existence incurred the wrath of not only the Zoroastrian Magi of his Persian homeland but also that of the later Christians and Emperors of China.

Mani’s parents are believed to have been members of the Elcesaites (Jewish-Christian) sect (at least as reported in the Cologne Mani-Codex). Mani claimed to have received revelations by a “Twin Spirit” when he was first 12 years of age and then twelve years later at the age of 24. He was then inspired to travel and spread his Messianic vision throughout the world. It is believed that he traveled for four decades.

The spread of Manichaeism was paralleled by the rise of the influence of Zoroastrianism and Christianity. Mani did win some support among the upper class nobles of the Sassanian nobles (Wuzurgan), but ultimately failed to win over Bahram I (r. 217-274 CE) who had the prophet enchained and imprisoned. Mani is believed to have died sometime in 274 or 277 CE. Undoubtedly the “orthodox” Magi, notably Grand Magus Kartir, were displeased with the theology of Mani’s messages.

Coin depicting Sassanian king Bahram I (r. 271-274 CE) (Source: Public Domain). Reversing his late father Shapur I’s (r. 240-270 CE) tolerance toward Mani and his religion, Bahram shackled and imprisoned the prophet after he “lost” a theological debate with the Zoroastrian Magi in the royal court. Mani is believed to have passed away in 274 or later in 277.

Coin depicting Sassanian king Bahram I (r. 271-274 CE) (Source: Public Domain). Reversing his late father Shapur I’s (r. 240-270 CE) tolerance toward Mani and his religion, Bahram shackled and imprisoned the prophet after he “lost” a theological debate with the Zoroastrian Magi in the royal court. Mani is believed to have passed away in 274 or later in 277.

What was the basis of Mani’s message? More precisely, what was in his message that inspired such repression in not only Persia, but also in Rome, China and later in the Balkans and France where Manichean ideas spread?

First, Mani was in a sense, the bringer of an international religion, one that was meant not just for Persia, but for all of humanity. He believed that the original teachings of Zoroaster, Buddha and Christ were incomplete (see Coyle, J.K. (2009). Manichaeism and Its Legacy, Brill, p. 13). Mani viewed his creed as the “Religion of Light” for the entire world (Coyle, 2009, p.13). He also claimed that the original teachings of Judeo-Christian religions (esp. Jesus Christ), Zoroaster and the Buddha had been corrupted.

Sixteenth century painting by Ali Shir-Navai of Mani the painter presenting one of his drawings to Bahram Gur (Source: Voice of America).

Sixteenth century painting by Ali Shir-Navai of Mani the painter presenting one of his drawings to Bahram Gur (Source: Voice of America).

The second theological aspect of Mani was in his dissection of the origin of evil. Mani denied the Omnipotence of God; he viewed two equal but opposing powers locked in conflict. The notion of opposing powers is reminiscent of the “Good versus Evil” dualism of Zoroastrianism. In this dynamic, each individual is a battleground between good and evil. But Mani’s version of evil diverges widely from Zoroastrianism, which views the good as superior to evil. Mani, also in contrast to Zoroastrianism, believed that the world had been created by a Satanic demiurge. Therefore, all material existence is seen as evil, such that salvation entails one’s complete liberation from material existence. This is not the case with Zoroastrianism where creation and material existence are not seen as “evil“. Mani, however believed that “particles of light” from the “Kingdom of Light” had been trapped in material form. Thus, in Mani’s view, even marriage and the birth of children was considered “evil“. Mani explained the birth of children as the process in which “particles of light” were bought down into “evil” material existence as the result of the union between men and women. Mani’s views of marriage and children were of course anathema to the doctrines of the Christian Church and Zoroastrianism.

Manicheans in Rome

Manichaism reached Rome by 280 CE through Mani’s Apostle Psattiq. The movement had already made inroads in Roman-ruled Egypt four decades earlier (in the 240s CE), and by the 290s CE, the Fayumm region of Egypt was heavily influenced by Manicheans. Manichean monasteries were in existence in Rome by the early 4th century CE, during the time of the Christian Pope Miltiades. Emperor Diolectian (284-305 CE) had already issued an edict, stating that the Manicheans be “condemned to the fire with their abominable scriptures”.

“St. Augustine of Hippo in his Study” as portrayed in 1480 by Sandro Botticelli (Source: Public Domain). Interestingly, St. Augustine had been a Manichean for 9 years until his conversion to Christianity in the aftermath of Emperor Diolectian’s edict (284-305 CE) condemning the Manicheans. Despite his conversion, it is believed that St. Augustine’s Manichean past influenced his later Christian writings.

“St. Augustine of Hippo in his Study” as portrayed in 1480 by Sandro Botticelli (Source: Public Domain). Interestingly, St. Augustine had been a Manichean for 9 years until his conversion to Christianity in the aftermath of Emperor Diolectian’s edict (284-305 CE) condemning the Manicheans. Despite his conversion, it is believed that St. Augustine’s Manichean past influenced his later Christian writings.

Apparently, Diolectian did not succeed in stamping out the Manicheans. Over eight decades after Diolectian, Rome’s Christian community demanded that Emperor Theodosius I (379-395 CE) strip the Manichaeans of all their civil liberties. Theodosius obliged by going further: he issued a decree for the death of Manichaean monks (382 CE). Interestingly, St. Augustine of Hippo (354-430 CE) converted to Christianity from Manichaeism shortly after Theodosius’ declaration. In the same declaration, Theodosius had made the “official” proclamation that Christianity was the only legitimate religion of the Roman Empire.

Emperor Theodosius I (379-395 CE) (Source: Annoyzview) issued a harsh edict ordering Manichean monks to be put to death. Despite such stern measures, Rome’s Christian religion failed to completely stamp out the followers of Mani who apparently gave rise to a number of “heresies”, one of these having been the later Cathars of southern France.

Emperor Theodosius I (379-395 CE) (Source: Annoyzview) issued a harsh edict ordering Manichean monks to be put to death. Despite such stern measures, Rome’s Christian religion failed to completely stamp out the followers of Mani who apparently gave rise to a number of “heresies”, one of these having been the later Cathars of southern France.

Creeds influenced by Manicheaism maintained a sporadic existence in Northern Italy, Spain, France, the Balkans, Mesopotamia, Central Asia, Western China, Tibet, India and North Africa, centuries after the death of Mani in Persia.

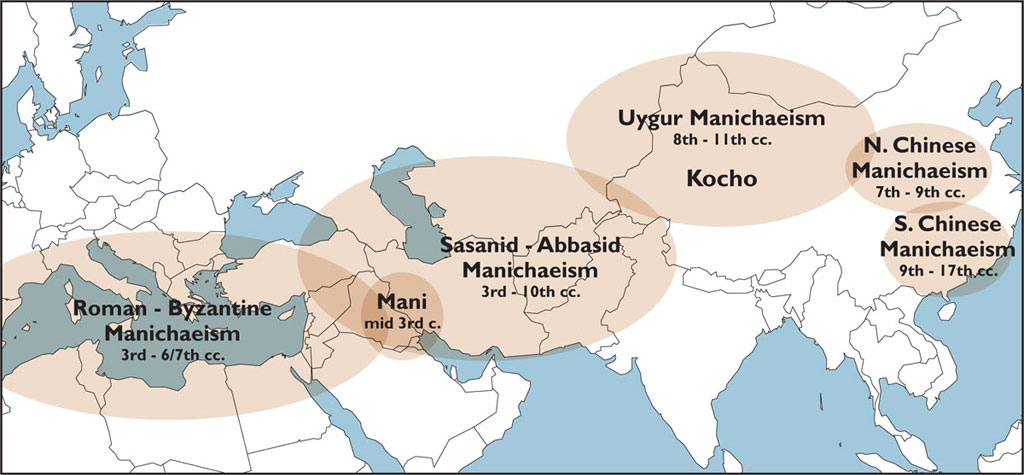

Map detailing the spread of Manicheaism (Source: Voice of America).

Map detailing the spread of Manicheaism (Source: Voice of America).

Manicheans in China

It is believed that the Manichean creed had arrived in China by the late 600s CE, however recent archaeological discoveries indicate that Mani’s followers had already arrived by the 550s CE (La Vaissière, Etienne de, “Mani en Chine au VIe siècle.” Journal Asiatique, 293–1, 2005, p. 357–378). Manichaeism adapted to Chinese Buddhism to win over converts. For example the Aramaic Karia (the “call” from world of light to world of darkness to those needing rescue) was equated to the Chinese Guan Yin and Buddhism’s Sanskrit term Avalokitesvara (watching/recognizing worldly wounds).

A depiction of Mani in the Duhuang caves of China; note the “Buddha-like” appearance of this statue (Kaveh Farrokh’s lectures at The University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division , Stanford University’s WAIS 2006 Critical World Problems Conference Presentations on July 30-31, 2006). Mani’s followers often adapted to the local beliefs and traditions of the regions they traveled to in order to win over converts to their religion.

A depiction of Mani in the Duhuang caves of China; note the “Buddha-like” appearance of this statue (Kaveh Farrokh’s lectures at The University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division , Stanford University’s WAIS 2006 Critical World Problems Conference Presentations on July 30-31, 2006). Mani’s followers often adapted to the local beliefs and traditions of the regions they traveled to in order to win over converts to their religion.

Emperor Xuanzong (712-756) of the Tang dynasty banned local conversions to Manicheanism in 732 CE , but this apparently failed to stem the spread of the creed. Over one century later for example, the Ta-yun Kuang-ming Su region of the metropolis of Chang’An featured a Manichean church as late as the 850s CE. This would helped explain Emperor Wuzong’s (840-846 CE) harsh official edict to slay all Manichean priests (it is is believed that over half of these were killed).

Tang Chinese Emperor Xuanzong (712-756) (Source: Public Domain) issued a decree banning conversions to Manicheanism, but this did little to curb the spread of the religion in China. This resulted in much harsher measures after Xuanzong, but elements of the movements resurfaced in later Medieval times, notably the Red Turban rebellion in 1351-1368.

Tang Chinese Emperor Xuanzong (712-756) (Source: Public Domain) issued a decree banning conversions to Manicheanism, but this did little to curb the spread of the religion in China. This resulted in much harsher measures after Xuanzong, but elements of the movements resurfaced in later Medieval times, notably the Red Turban rebellion in 1351-1368.

Manicheans in Central Asia: Soghdians and Uighur Turks

As the Manicheans spread into Central Asia, they soon adapted to the ideas of the region’s local Iranian-speakers. Manichean deities now morphed into the distinctly Zoroastrian Yazatas such as Pid e Wuzurgih. The spread of Manicheaism in Central Asia was thus also facilitated by numbers of local (Iranian-speaking) Soghdians who had adopted the faith. These most likely played a key role in spreading Manichaeism among Central Asia’s Turkic peoples.

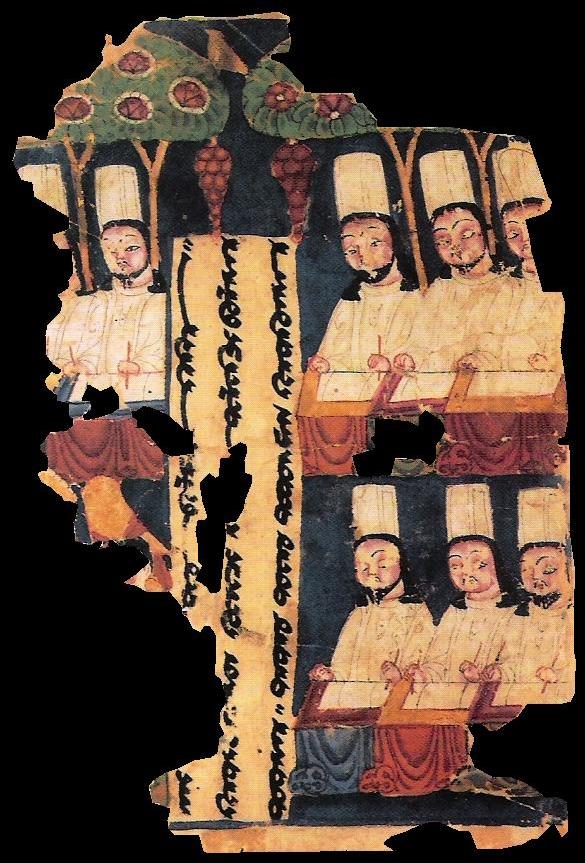

A Kocho manuscript (Source: Voice of America) showing Uighur Manichean priests engaged in writing.

A Kocho manuscript (Source: Voice of America) showing Uighur Manichean priests engaged in writing.

Manicheaism made major inroads among the Uighur Turks. The Uighur ruler, Khagan Boku Tekin (759–780 CE), commissioned a three-day discussion with Manichean preachers in 763 CE. This resulted in the Khagan’s conversion to Manicheaism. Shortly thereafter, high ranking priests were dispatched from the Babylonian headquarters to the Uighur Empire. Manichaeism remained as the Uighur state religion for nearly a century before the collapse of the empire in 840 CE.

The Cathars of Southern France

Manicheaism is believed to have had strong links to the Cathar movement of southern France. The Cathars are known from their presence in the 12-13th centuries CE, however the creed of Mani had arrived into Southern France centuries earlier. Hilary of Poitiers wrote in 354 CE (during Roman rule) that the Manichaean faith had already become a powerful force in Southern Gaul. True or not, the Christian Church would often accuse the Cathars of ”Manichean heresies”. While the Cathars denied charges of Manicheanism, their beliefs indicated otherwise.

Medieval depiction of a dispute between Saint Dominic and the Cathars, also known as the Albigensians (Source: Kaveh Farrokh’s lectures at The University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division). Interestingly, the Cathars denied charges of being Manicheans, yet their belief systems were wholly consistent with Mani’s teachings.

Medieval depiction of a dispute between Saint Dominic and the Cathars, also known as the Albigensians (Source: Kaveh Farrokh’s lectures at The University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division). Interestingly, the Cathars denied charges of being Manicheans, yet their belief systems were wholly consistent with Mani’s teachings.

Like Mani, the Cathars Believed that the world had been created by a Satanic demiurge. The Cathars also viewed material existence as evil therefore one must strive to liberate oneself from it to achieve salvation. They also believed in re-incarnation and were vegetarian. The Cathars also believed in the equality of men and women. However (again like Mani) the Cathars rejected the notion of producing children and thus shunned the institution of marriage and family in favor of “living together”. Cathar Church organization also appears to have had Manichean influence. Persecutions of the Cathars began from 1184, and shortly after they were condemned as heretics by Pope Innocent III (papacy: 1198-1216). The Cathars were completely crushed by the 1260s.

The Paulicians of Armenia

Another sect believed to have had Manichean influence were the Paulicians. This began as a Christian breakaway sect in Armenia and the eastern parts of Byzantine Empire (650-844 CE). The movement was founded by an Armenian named Constantine, who hailed from Paytakaran. The movement was named after a Bishop of Antioch, Paul of Samosata. The first official Paulician church sprung in Kibossa, Armenia in 660 CE.

Constantine’s studies of the Gospels and the Epistles, resulted in him combining dualistic and Christian beliefs. He believed that the contemporary Church misled the people. Constantine’s solution was to have the Christians return to the “original” Church of Paul. Interestingly, Constantine adopted the name “Silvanus“.

Paulicians being subjected to massacres, as depicted in the Madrid Skylitzes (Source: Public Domain). Armenian Paulicians were transferred in the hundreds of thousands to Eastern Europe by the Byzantines, a factor which appears to have contributed to the rise of the Bogomils in Bulgaria.

Paulicians being subjected to massacres, as depicted in the Madrid Skylitzes (Source: Public Domain). Armenian Paulicians were transferred in the hundreds of thousands to Eastern Europe by the Byzantines, a factor which appears to have contributed to the rise of the Bogomils in Bulgaria.

Despite persecutions by the Byzantines and breaking into sectarian rivalry, the Paulicians actually succeeded in establishing an independent state in Tephrike (modern Sivas province, Turkey) by 844 CE. Byzantine Emperor Michael III (r. 842-867 CE) persecuted the Paulicians and killed their leader Karbeas in 863 CE. Persistent Byzantine persecutions of the Paulicians resulted in the latter often siding with the Caliphates. Paulicians for example appear to have fought alongside the Arabs against the Byzantines in the Battle of Lalakon (863 CE). The Byzantine Emperor Constantine V (741–775) finally transferred large numbers of Paulicians to Thrace. Byzantine Emperor Basil I (867–886) abolished the Paulician state of Tephrike in 871 CE, forcing its survivors to flee to Syria and Armenia. The Byzantine transfer of Armenians into Europe continued. Byzantine Emperor John I Tzimiskes (969-976 CE) settled 200,000 Armenian Paulicians in Philipopolis, Thrace (970 CE).

Paulicians who remained in Anatolia were to experience Ottoman persecution in the late 1600s, forcing its survivors to flee into Europe and even across the Danube. Pockets of Paulician communities survived in Eastern Europe as late as the 1870s, notably in Bulgaria, Serbia and Romania. After Russia conquered the Caucasus from Iran (finalized by the Treat of Turkmenchai 1828), Russian troops entering Armenia discovered numbers of Paulicians still practicing their faith in the region.

The Bogomils of Eastern Europe

Another movement believed to be linked to the Manicheans were the Bogomils of the Balkans. As noted previously, Byzantine Emperors Constantine V (741–775) and John I Tzimiskes (969-976 CE) had transferred large numbers of Paulicians to Thrace (recall 200,000 Armenian Paulicians settled in Philipopolis, Thrace in 970 CE). These became Bulgarian speaking, and were known by the Bulgars as the Pavlikiani. It is possible that these same Paulicians became one of the roots of the ensuing Bogomil movement.

The Bogomil movement is generally traced to the time of Peter I of Bulgaria (927-969). The Bogomils themselves are generally described as a Gnostic movement which arose as a reaction against the state-clerical repression of the Byzantine Church. Slavonic sources however claim Bogomil doctrines as Manichean.

The famous fresco of Saint Simeon, same as Serbian Prince Stephan Nemanja (r. 1166-1196) at King’s Church in the Studenica monastery (Source: Public Domain).

The famous fresco of Saint Simeon, same as Serbian Prince Stephan Nemanja (r. 1166-1196) at King’s Church in the Studenica monastery (Source: Public Domain).

Bogomilism was essentially (like the creed of Mani) a dualistic doctrine in which the world is seen as divided by God (Good) and Satan (Evil). God is seen as ruling the Spiritual world with Satan ruling the material world. Like Manicheaism, every material being and manifestation is seen as the work of Satan. The Bogomils were also, in a sense, “anarchists” in that they opposed established government and church, making them somewhat like modern-day anarchists.

The Bogomil movement gained momentum in Eastern Europe by the 1220s, but the creed had already been introduced into the Kievan Rus in 1004, just 25 years after Christianity had been introduced into the region. There are citations of a certain Bishop “Adrian” (1004) followed by Bishop “Dmitri” preaching about the Bogomils (1125). Both the Kiev Rus and Bulgarian churches attempted to repress the Bogomils, but pockets of these may have survived as late as the 16th Century.

Kulin Ban’s plate discovered in Biskupići, near Visoko (Source: Public Domain). Kulin Ban welcomed the Bogomils into Bosnia.

Kulin Ban’s plate discovered in Biskupići, near Visoko (Source: Public Domain). Kulin Ban welcomed the Bogomils into Bosnia.

The Bogomils also spread westward from Bulgaria into Serbia, especially in 12th century, where they became known as the Babuni. Serbian prince Stephan Nemanja and the Serbian council were quick to declare declare the Babuni as heretics, and expelled them from Serbia in the 12th century.

The celebration of “Surva” in modern-day Bulgaria. Local lore traces this festival to the Iranian God Zurvan. This folklore system appears to be linked to the Bogomil movement. Interestingly, much of the Surva theology bears parallels with elements of Zurvanism and Zoroastrianism (Picture Source: Surva.org).

The celebration of “Surva” in modern-day Bulgaria. Local lore traces this festival to the Iranian God Zurvan. This folklore system appears to be linked to the Bogomil movement. Interestingly, much of the Surva theology bears parallels with elements of Zurvanism and Zoroastrianism (Picture Source: Surva.org).

The Serbian expulsions however did little to stem the westward spread of the Bogomils. These arrived from Serbia (from where they had been recently expelled) into Bosnia and Dalmatia, where they became known as the Pataranes. The Bosnian King Kulin Ban (1180-1204) welcomed the Pataranes, incurring deep suspicions from the Catholic Church. Pope Innocent III (papacy: 1198-1216) was especially wary of these Balkan developments from at least 1199. More “converts” into Bogomilism continued, notably the Prince of Herzegovina and the Roman Bishop of Bosnia. Altars and crosses were removed with distinctions between the clergy and Congregation becoming negligible. Alms were also set aside by the followers to support the evangelistic cause of the Bogomils. The successes of the Bogomils in the Balkans may be partly attributed to the local populations’ reaction to the excesses of the Catholic and Orthodox Churches.