Few realize that China is host to s small population of Iranian-speakers who are Tajiks akin to those in Tajikestan and fellow-Iranic peoples in Iran, Afghanistan, Caucasia and the Kurds of Iraq, Turkey and Syria.

More research is required in the study of these peoples in China to help address current misconceptions in this domain. As asserted by Dr. William Saffron:

“There is a group of 26,000 Indo-Iranian speakers in China in the Pamirs near the Karakorum highway…the Chinese government…calls them Tajiks…However Tajik is not spoken in China” (Saffron, 1998, pp.75).

This claim is contradicted by TV programs in Chinese television which show Chinese Tajiks singing in Tajiki (essentially akin to Persian) – kindly consult U-Tube links below:

Chinese-Tajik girl sings a Persian-Tajiki song at China’s Shisu University

Tajikan – Tajiks on Chinese TV from Taj Qurghan of China

Chinese scholars have provided somewhat more accurate information on these Chinese-Tajiks. One example is Dr.’s Du and Yip who note that:

“Most Tajiks in China speak Tajik…” (Du & Yip, 1993, pp.93).

The accent of this particular Chinese-Tajiki is phonologically similar to those Persian vernaculars seen in Afghanistan, parts of eastern Khorasan and of course Tajikestan.

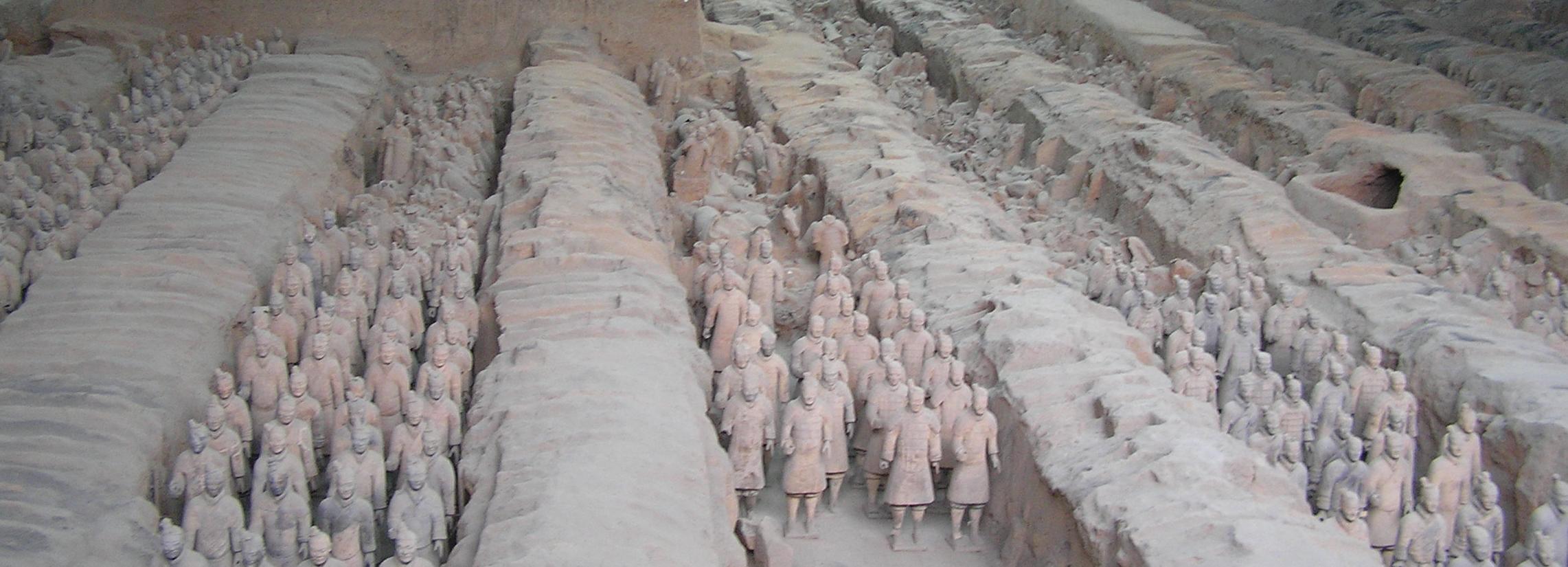

Iran and China have enjoyed cultural links harking back to late Achaemenid times (400s to 330 BC). Chinese archaeologists unearthed evidence that non-Chinese workers of Iranic origins helped build the terracotta army mausoleum (near the north-west city of Xian). This is the resting place of China’s first emperor, Qin Shi Huang, who died more than 2,200 years ago.

The Terracotta Army near the northwest city of Xian which contains (at least) 8,000 life-sized terracotta warriors & horses. It is estimated that up to 700,000 laborers worked on the imperial Tomb. Chinese archaeologists have discovered that Iranian craftsmen dated to the Achaemenid era worked alongside their local Chinese colleagues to construct these figures.

Emperor Qin Shi Huang who unified China. His legacies include building the foundation of the first Great Wall of China and the great mausoleum bearing the massive terracotta army.

Professor Tan Jingze, an anthropologist with Fudan University, told the Chinese Xinhua News Agency:

“One sample has typical DNA features commonly owned by the Parsi

[Zoroastrians]… the Kurds … and the Persians in Iran…”These finds are highly significant as this strongly suggests that Iranian craftsmen of the Persepolis tradition were present in Qin China. Earlier studies had suggested that the first Chinese-Iranian contacts had occurred later during Han dynasty (206 BC-220 CE).

Iranian-speaking Tajik women from China. These are mainly clustered in the Karakorum region.

There are also Tajik-speaking residents in the predominantly Turkic-speaking Uighur region of Xinxiang province of northwest China, especially in the osasis city of Kashgar.

Tajik-speakers from Kashgar.

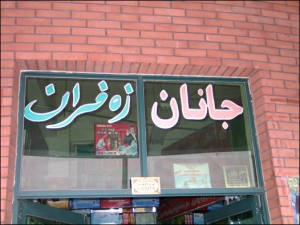

Shop with modified Persian script in Kashgar, northwest China. This is one of the legacies of the historical silk route straddling between ancient Iran and China, having its orgins in the pre-Islamic era and enduring well into the post-Islamic era. The shop sign reads “Jaanan Zaaferan” or Jaanan’s saffron.

Further Readings:

Bernstein, W.J. (2009). A Splendid Exchange: How Trade Shaped the World. Grove Press.

Du, R. & Yip, V.F. (1993). Ethnic Groups in China. Science Press.

Hayashi, R. & Ricketts, R. (1975). The Silk Road and the Sosho-in. Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Saffron. W. (1998). Nationalism and Ethnoregional Identities in China. Routledge Publishers.