Next to Iranian museums the State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg has one of the most beautiful collections of Persian shamshirs in their collection. The following article below by Dr. Manouchehr M. Khorasani (see also his article on the subject in Academia.edu) shows some of these magnificent pieces:

A 19th century ritual sword (šamšir-e mostāqim: straight sword) from Iran (Source: M. Khorasani Consulting). It was acquired in 1931 and was formerly held in the collection of Count Sergey Sheremekev’s collection.

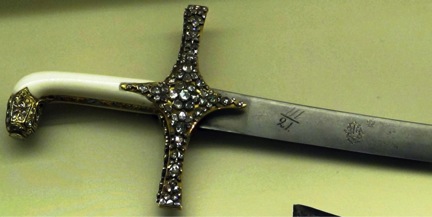

A magnificent Persian shamshir with a Safavid period blade and Qajar-period fittings. the State Hermitage Museum provides the following description:

“Steel, gold, leather, precios stones, enamel, forging, casting, chasing, carving. Iran, First half of the 19th century. Acquired in 1885-1886 from the Armoury of Tsarskoye Selo“.

The bolčāq ﺒﻠﭽﺎﻖ (crossguard) of the shamsir is made of gold and inserted with diamonds and precious stones as well as the kolāhak (pommel cap). The handle slabs are made of ivory. The book Lexicon of Arms and Armor from Iran: A Study of Symbols and Terminology, Manouchehr Moshtagh Khorasani (2010) provides the following information on the term bolčāq ﺒﻠﭽﺎﻖ:

bolčāq ﺒﻠﭽﺎﻖ: (Haft Darviš) (n) handguard, crossguard of a sword; the term bolčāq is also used in the manuscript on futuvvat called “Haft Darviš” (seven dervish) which was probably written in naskh and is undated (Afshari & Madayeni, 1381:123). Afshari and Madayeni (1381:123-4) attribute this book to the 11th or 12th century (17 or 18 A.D.) as it belonged to the library of Etezadol Saltane (the minister of science and mines) in 1296 hegira (1876 A.D.). Afshari and Madayeni (1381:184) quote from this manuscript which says that one day a butcher who was a jawanmard went to Ali, kissed his hand and asked for help saying that his kārd became blunt very quickly. Ali touched the bolčāq of his Zulfagar (the famous legendary sword attributed to Ali), rubbing it so long that a kardmal (a knife sharpener) was created. Afshari and Madayeni (1381:184) further explain that bolčāq is originally a Turkic term describing the handguard which separates the qabze (handle) from the sword’s blade, tiqe-ye šamšir.

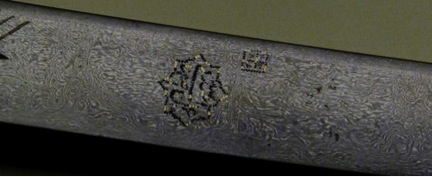

The magnificent Persian crucible Damascus steel blade as the pattern of Kirk nardeban (forty steps/rungs) in the western literature. Persian manuscripts call this patttern pulād-e jŏhardār-e qerq nardebān : (New Persian) (n + adj + adj + n) watered steel with ladder pattern; a type of crucible steel with ladder pattern; known as forty ladder rungs (Romanowsky,1967b/1346:78). Note that pulād ﭘﻮﻻﺩ (n) means “steel,” jŏharﺟﻭﻫﺮ(n) means “watered steel,” dār ﺪﺍﺭ derives from the verb dāštan ﺩﺍﺷﺘﻦ (to have), qerqﻗﺮﻖ (adj) means “fourty,” and nardebān ﻧﺮﺩﺑﺎﻥ (n) means “ladder” This pattern is also known as čehlband ﭼﻬﻞﺑﻨﺪ (forty straps) (see Lexicon of Arms and Armor from Iran; A Study of Symbols and Terminology (2010) by Manouchehr Moshtagh Khorasani, Tübingen: Legat Verlag. For a detailed discussion of this pattern see Arms and Armor from Iran: The Bronze Age to the End of the Qajar Period (2006) by Manouchehr Moshtagh Khorasani, Tübungen: Legat Verlag.

The blade has a beautiful gold-inlaid maker’s mark which reads “amal-e Assadollāh Esfahāni (Isfahāni)” : (the work of Assadollāh Esfahāni).

This maker’s mark appears on a number of high quality Persian swords. Other variants of this signature also exist as amal-e Assadollāh (the work of Assadollāh), Amal-e Assad Esfahāni (the work of Assad Esfahāni), and Assadollāh Esfahāni (Assadollāh Esfahāni) – for more information see Moshtagh Khorasani (2006:156-163). Dated swords with this maker’s mark complicate the issue even more. There are seven dated examples that, rather than solving the mystery behind the smith Assadollāh’s life, only complicate the matter as the time span over which these swords are purported to have been constructed is too long for a normal human life, let alone the active life of a smith. Among the swords discussed in the book Arms and Armor from Iran: The Bronze Age to the End of the Qajar Period, the earliest date is 992 Hegira (1583 C.E.), and the latest is 1135 Hegira (1722 C.E.), a time span of 139 years (Moshtagh Khorasani, 2006:156-163). Even the positioning of the individual words in this phrase varies from sword to sword. Taking all these factors into consideration, it seems unlikely or even fundamentally implausible that a single smith named Assadollāh produced all these blades. It seems feasible and probable that “Assadollāh” ﺍﺴﺪﺍﷲwas a title of honor signifying the highest level of mastery in swordmaking. The theory that some of these inscriptions were counterfeited to add to the value of a sword may be true of later swords bearing cartouches where one finds poorly executed inlayings or even overlayings, but all examples presented in the book mentioned above have inscriptions with finely executed calligraphy and workmanship and exhibit outstanding inlaying techniques. If one assumes that the name “Assadollāh” ﺍﺴﺪﺍﷲwas the highest title given to an Iranian smith who had attained a very high level of mastery in making swords, the mystery of the existence of a variety of handwriting and calligraphy styles over a long period of time appears to be solved. As mentioned by Mayer (1957-9:1), a person counterfeiting a fraudulent cartouche would most likely imitate the original as precisely as possible in order to deceive buyers since he attempted to sell his swords under a fake name. Additionally, a counterfeiter would surely have ensured that the date on forged cartouches exactly matched the era of Šāh Abbās Safavid if there were only one famous smith named Assadollāh during the relevant period. Another fact reinforcing the hypothesis that “Assadollāh” ﺍﺴﺪﺍﷲwas presumably an honorary title bestowed during the Safavid period is that there are three dated swords bearing the phrase of Amal-e Assdollah Esfahāni from the same time period, namely Amal-e Assadollāh Esfahāni 116, Amal-e Assadollāh Esfahāni 117 , and Amal-e Assadollāh Esfahāni and Bande-ye Šah-e velāyat Abbās saneye 135 (see Moshtagh Khorasani, 2006:156-163), all originating during the period of Šāh Sultan Hossein Safavid, who ruled from 1105-1135 Hegira (1694-1722 A.D.). However, all three swords look different in many respects, especially regarding the handwriting style. This is further evidence that, at least during the period of Šāh Soltān Hussein Safavid’s reign, various smiths signed blades using the signature Amal-e Assadollāh Esfahāni and further corroborates the theory that Assadollāh ﺍﺴﺪﺍﷲwas, indeed, an honorary title. . . . . . . .

For more information on this topic read the entry amal-e Assadollāh Esfahāni in the Lexicon of Arms and Armor from Iran; A Study of Symbols and Terminology (2010) by Manouchehr Moshtagh Khorasani, Tübingen: Legat Verlag. For more information see:

and

The next gold-inlaid cartouch is the symbol of bodduh in numbers;

bodduhﺒﺩﻭﺡ : (Dehkhoda) (n) the name of a genie or an angel who can do miraculous things, whose name is written by letters or numbers in occult sciences. Certain characteristics are attributed to this angel. For example, if one writes its name on an envelope, the letter will certainly arrive. Therefore, it serves as the angel for protecting the letters. It is a secret telesm ﻂﻠﺴﻢ(talisman). The are certain beliefs regarding this sign. For example, when a traveller has this sign, he would be able to travel day and night without getting tired, or a pregnant woman would be able to give birth without fearing a miscarriage. The term bodduh ﺒﺩﻭﺡ is also used to conjure feelings of love. It consists of the even numbers 2, 4, 6, 8 or 8, 6, 4, 2. The numbers are equivalent to the lettersﺐ, ﺩ, ﻭ, and ﺡ of huruf-e jomal ﺠﻤﻝ ﺣﺮﻭﻑ. Anandeaj reports that bodduh is the name of an angel who died and left this world and whose name is gold-inlaid on swords and daggers and is used for protection. (Digital Lexicon of Dehkhoda). For more information on this topic read the entry bodduhﺒﺩﻭﺡ in the Lexicon of Arms and Armor from Iran; A Study of Symbols and Terminology (2010) by Manouchehr Moshtagh Khorasani, Tübingen: Legat Verlag.

For another classification of Persian crucible steel see:

Varband (scabbard fittings) are also made of called and inserted with diamonds.

The wooden scabbard consists of two parts glued to each other and covered with the precious sāqari ﺳﺎﻏﺭﻯ or kimoxt ﻜﻴﻤﺧﺖ (shagreen leather), which is the skin of the back of the horse and donkey that is used as a special leather. The book Lexicon of Arms and Armor from Iran; A Study of Symbols and Terminology (2010) (Manouchehr Moshtagh Khorasani, Tübingen: Legat Verlag) provides the following entry on this type of leather:

sāqari ﺳﺎﻏﺭﻯ: (Rostam al Tavārix) (n) shagreen leather (Āsef, 2003/1382:90). Shagreen leather was often made from the skin of jackass (donkey) hindquarters. According to Dehkhoda, saqari ﺳﺎﻏﺭﻯ is a type of leather made of the hide of jackass hindquarters. Its surface is rough. Saqari ﺳﺎﻏﺭﻯ can be obtained from the hindquarters of a horse as well as zebra hide. With regard to the processing and tanning of shagreen leather, Chardin (268) states that significant amounts of this leather was made in Iran and exported to the Indies (India), Turkey, and neighboring kingdoms. He states that shagreen was made from jackass (donkey) hindquarters, and a seed called toxm casbini, (seed of casbin that is said to be black, hard, and larger than the mustard seed). Toxm ﺗﺨﻡ stands for both “egg” and “seed” in Farsi as Chardin rightly says. He further states that the name shagreen comes from the Persian word saqari, meaning “hindquarters.” According to Chardin, this was the name of any animal they rode on, similar to the English word “steed,” and this name was given to this sort of hide because it was made of an jackass’s hindquarters. The coarse hides were dressed by tanners with lime. They used salt and galls in the tanning process instead of bark, which, according to Chardin, was sufficient due to the hot Iranian climate. Floor (2003:383) quotes Olmer, who stated that sagari was primarily prepared in Yazd and describes it as a type of tanned leather made of the skins of a horse or donkey and, sometimes, even that of a cow. The cleaning of the skin was performed using almost the same method as that used for sheepskin. Olmer explained that before applying the barley treatment to the skin, the tanners covered them with small, dried grains and let them dry. The grains worked their way into the skin, resulting in unevenness of the surface and a grained appearance. After the skins dried, they were soaked in water with fermenting barley, causing them to swell. The workers, then, used somāq ﺴﻤﺎﻖ leaves (rhum coriaria) for the tanning process. Olmer reports that these leaves contained much tannin. Floor (2003:383) also quotes Consul Abbot, who provides more information on the making of shagreen leather in Esfahān. He said that this leather was made from the raw hides of horses. They spread the wet skin on a level surface, threw small, round seeds over it, and trod upon it. After the skin partially dried, they shook off the seeds, shaving the surface of the hide to remove all but the indented parts that gradually rose again to their former level, producing the bumps on the shagreen. Then, they applied a preparation of copper and sal ammoniac to the reverse side, which penetrated to the front, coloring it green.

The scabbard chape tah-e qalāf is also made of gold.

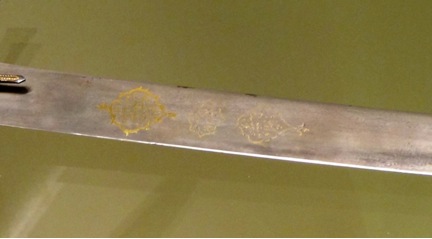

This Persian shamshir has engraved and gold-inlaid spatulated quillons. The pommel cap is also gold-inlaid. The handle slabs are made of walrus ivory. The blade is made of Persian crucible damascus steel. The blade has three cartouches. The upper and middle cartouches are the original ones from the Safavid period to the blade and are gold inlaid. The lower cartouche is gold-overlaid and added to the blade during the early Qajar period.

The upper cartouche reads bande-ye šāh-e velāyat Safi . The book “Lexicon of Arms and Armor from Iran: A Study of Symbols and Terminology” provides the following entry for this phrase:

bande-ye šāh-e velāyat Safi : (New Persian)(n + n + n + n) literally means, “The subject/ slave of the kingdom/ dominion/trusteeship of Ali, Safi.” This translates into the following: “Safi is the representative of Ali’s rule and acts on his behalf.” Note that bande ﺑﻨﺪﻩ (n) means “slave/subject,” šāh ﺷﺎﻩ (n) means “king,” and velāyat ﻮﻻﻴﺕ (n) means “country, trusteeship,” and Safi ﺼﻔﻰ (n) is a king’s name. ……

For the same cartouche on royal pieces of Iranian Military Museums see “Arms and Armor from Iran: The Bronze Age to the End of the Qajar Period” (Moshtagh Khorasani, 2006444, cat.80; 446, cat.81; 448, cat.82).

The gold-inlaid cartouche in the middle reads Yekšanbe Helāl Šahr Kār Mehr Ali which means “Sunday the first day of the month the work of Mehr Ali.”

Note that a smith named Mehr Ali made a dated pišqabz in 1109 hijra, dedicated to Mohammad Mehdi Khan Zand. For more information and to see the dagger consult the book “Arms and Armor from Iran: The Bronze Age to the End of the Qajar Period”, Manouchehr Moshtagh Khorasani, 2006, which explains:

The date, 1190 hegira, is 1776 A.D.

The lowest cartouche is the royal seal of Fath Ali Shah Qajar which reads “Abu al Seif al Soltān Fath Ali Šāh Qājār” (The father of the sword Fath Ali Shah Qajar). A number of royal shamshirs attributed to Fath Ali Shah Qajar which are kept in the Military Museum of Tehran have the same cartouche which is the royal seal of Fath Ali Shah Qajat. To see these examples see “Arms and Armor from Iran: The Bronze Age to the End of the Qajar Period”, Manouchehr Moshtagh Khorasani, 2006, Tübingen: Legat Verlag.

A Persian shamshir with a typical wedge-shaped blade with a high curve. The handle slabs are made of ivory.

The blade has a beautiful crucible damascus blade with the pattern pulād-e jŏhardār-e mošabak, watered steel with net pattern; a type of crucible steel with woodgrain pattern (Romanowsky, 1967b/1346:78). For more information on this pattern see Lexicon of Arms and Armor from Iran; A Study of Symbols and Terminology (2010) by Manouchehr Moshtagh Khorasani, Tübingen: Legat Verlag.

For another classification of Persian crucible steel see:

The Persian blade has three catouches: The upper cartouche is a bodduh sin in numbers. The lower is a maker’s mark amal-e Assadollāh (Work of Assadollah), The carouche in themiddle reads: bande-ye šāh-e velāyat Abbās.

For the meaning of this pharse see the entry bande-ye šāh-e velāyat Abbās from the book Lexicon of Arms and Armor from Iran; A Study of Symbols and Terminology (2010) by Manouchehr Moshtagh Khorasani, Tübingen: Legat Verlag:

bande-ye šāh-e velāyat Abbās: (New Persian) (n + n + n + n) literally means, “The subject/ slave of the kingdom/ dominion/trusteeship of Ali, Abbās.” This translates into the following: “Abbās is the representative of Ali’s rule and acts on his behalf.” Note that bande ﺑﻨﺪﻩ (n) means “slave/subject,” šāh ﺷﺎﻩ (n) means “king,” and velāyat ﻮﻻﻴﺕ (n) means “country, trusteeship,” and Abbās ﻋﺒﺎﺱ (n) is a king’s name. For this inscription see Moshtagh Khorasani (2006b:430, cat.70; 432, cat. 73, 434, cat. 74; 435, cat. 75; 436, cat. 76; 438, cat. 78; 441, cat. 79; 451, cat.85; 453, cat.86; 454, cat.87; 456, cat.89; 475, cat.107; 481, cat.112; 526, cat.151; 541, cat.162).

Also part of the next entry from the same book:

bande-ye šāh-e velāyat : (New Persian) (n + n + n) the slave/subject of the king of that country/trusteeship. Note that bande ﺑﻨﺪﻩ(n) means “slave/subject,” šāh ﺷﺎﻩ(n) means “king,” and velāyat ﻮﻻﻴﺕ(n) means “country, trusteeship.” This is a phrase that frequently appears on Safavid blades is bande-ye šāh-e velāyat… in combination with the name of the Safavid king who ruled at that time. The phrase amal-e Assadollāh appears often with the phrase bande-ye šāh-e velāyat Abbās . According to Digital Lexicon of Dehkhoda, bande ﺑﻨﺪﻩ means “subject” or “slave.” Obviously, people who serve or inhabit the realm ruled by a king are his subjects. velāyat ﻮﻻﻴﺕmeans “kingdom” or “ruled land”; therefore, a king has a velāyat ﻮﻻﻴﺕ to rule. Dehkhoda further states that the person to whom velāyat-e Ali relates considers himself the representative of Imām Ali and, consequently, rules and governs on his behalf.

………………..

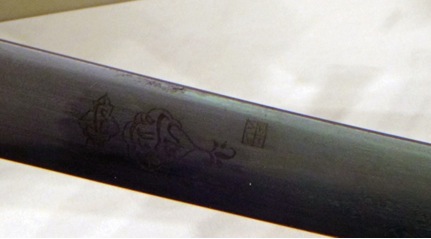

A Persian shamshir with a steel handle and a highly curved blade. The State Hermitage Museum states that this shamshir was acquired in 1885-1886. It was formerly held in the Armoury of Tsarskoye Selo.

The gold-inlaid maker’s mark reads “amale-e Kalbeali Esfahāni 1019” (The work of Kalbeaöo Isfahani 1019). 1019 stands for the Gregorian year 1610-1611- For more information see part of the entry amal-e Kalbeali from the book Lexicon of Arms and Armor from Iran; A Study of Symbols and Terminology (2010) by Manouchehr Moshtagh Khorasani, Tübingen: Legat Verlag:

amal-e Kalbeali: (New Persian) (n + n) the work of Kalbeali (dog of Ali). Note that amal ﻋﻤﻞ (n) means “work,” kalbﻜﻟﺐ (n) means “dog,” and Ali ﻋﻟﻰ (n) is the name of Hazrat-e Ali. The expression “The dog of Ali” is used to show the devotion of the maker to Hazrat Ali , the first Imam of the Shiites. This maker’s mark is also a mystery as different swords with different handwriting and calligraphy with this maker’s mark exist. The existence of different phrases of the signature of “Kalbeali” indicates that there were, indeed, different smiths who signed their swords with this title. There are three different types: a) amal-e Kalbali , b) amale-e Kalbeali Esfahāni, and c) amal-e Kalb-e Ali ibn Assad-e Esfahāni. The name “Kalbeali” is sometimes written as one word asﻜﻠﺒﻌﻠﻰ, and it is written in two words on other cartouches as well as ﻋﻠﻰﻜﻠﺐ. Even the reference to the father, Assadollāh, is different. One cartouche bears the expression, Ibn Assad Esfahāni , whereas another cartouche reads, Ibn Assad Zahābdār . The inscription, Valad-e Kalbeali ibn Assad Zahābdār, reveals that the smith wanted to stress that his grandfather had the title “Assadollāh” ﺍﺴﺪﺍﷲ, the highest level, or wanted to stress that he was a seyyed (descendant of the Prophet Mohammad’s family), for a detailed discussion of the maker’s mark of Kalbeali ﻜﻠﺒﻌﻠﻰ, see Moshtagh Khorasani (2006:163-167). Assuming that Assadollāh ﺍﺴﺪﺍﷲ was an honorary title, one is faced with the problem of interpreting the phrase Amal-e Kalbeali ebn Assad (“the work of Kalbeali the son of Assad”). In this regard, Mayer (1957-9:2) states that there were two sons of Assadollāh ﺍﺴﺪﺍﷲ, Kalbeali ﻛﻠﺒﻌﻠﻰ and Esmāil ﺍﺴﻣﺎﻋﻳﻞ. He asserts that only one blade is signed “The work of Esmāil son of Assadollāh. ………………………”

The blade has also a gold-inlaid bodduh sign in numbers.

A Persian shamshir with a curved blade and a raised backedge (yalman). The handle is the shape of karabela hilt. The downward quillons end up in dragon heads. The State Hermitage Museum attributes this shamshir to the late 17 century (or early 18th century) and adds that it was acquired in 1885-1886. It was formerly held in the Armoury of Tsarskoye Selo.

The handle slabs are made of ivory with the steel crossguard decorated with gold-overlaid floral design.

The blade has an engraved and gold-inlaid maker’s mark amal-e Mesri Mo’alam. For this maker’s mark see the book Lexicon of Arms and Armor from Iran; A Study of Symbols and Terminology (2010) by Manouchehr Moshtagh Khorasani, Tübingen: Legat Verlag which provides the following entry:

amal-e Mesri Mo’alam or amal-e Mo’alam Mesri : (New Persian) (n + n + n) the work of Mesri Mo’alam or the work of Mo’lam Mesri. Note that amal (n) means “work” and Mesri Mo’alam (n) is a name. A sword signed by amal-e Mesri and attributed to Sāh Safi is kept in the Military Museum of Tehran. For more information see Moshtagh Khorasani (2006:444, cat. 80; 538, cat.159).

The forte of the blade is also gold-overlaid in floral design and also the inscription in Persian reads:

Ze huše Falātun domaš tiztar [upper part]

Ze abruye deldār xunriz tar [lower part]

Its edge [literally, tail] is sharper than the intelligence of Plato! It sheds more blood than the eyebrows[1] of the beloved.[1] Persian literature always refers to eyebrows as one of the physical beauties of women (author’s observation). For the same inscription on Persian qaddāres see Arms and Armor from Iran: The Bronze Age to the End of the Qajar Period by Manouchehr Moshtagh Khorasani, 2006, Tübingen: Legat Verlag.

A highly curved Persian shamshir with a handle with walrus ivory slabs. It has a wooden scabbard covered with shagreen leather. The State Hermitage Museum attributes this shamshir to the first half of the 18 century and adds that it from the Winter Palace. The crossguard (bolčāq) has an engraved inscription Bismellah al Rahman al Rahim (In the name of God, most benevolent, ever-merciful) in the gilded background.

A highly curved Persian shamshir with a handle with walrus ivory slabs. The State Hermitage Museum attributes this shamshir to the 17- 18 century and adds that it from the Winter Palace. The crossguard (bolčāq) is beautifully gold-overlaid with the inscription Bismellah al Rahman al Rahim (In the name of God, most benevolent, ever-merciful).

A Persian shamshir made of crucible steel with a raised backedge (yalman). The handle slabs are made of walrus ivory. The steel crossguard is decorated with gilded image of a lion hunting a deer (for a detailed explanation of this symbol see “Arms and Armor from Iran: The Bronze Age to the End of the Qajar Period” by Manouchehr Moshtagh Khorasani (2006).

The upper gold-overlaid cartouche reads Bismellah al Rahman al Rahim( In the name of God, most benevolent, ever-merciful). The length of the blade is gold-overlaid with a Persian poem.

For a technical analysis of Persian crucible steel see:

A highly-curved Persian shamshir with a typical wedge-shaped blade. The wooden scabbard is covered with shagreen leather.

The handle slabs are made of walrus ivory and the steel crossguard and pommel cap are engraved. The State Hermitage Museum attributes this shamshir to the 18 century and adds that it was acquired in 1885-1886. It was formerly held in the Armoury of Tsarskoye Selo.

A highly-curved Persian shamshir with downward quillions and a karabella hilt. The crossguard is made of steel and decorated with gilded floral design. The handle slabs are made of stag horn.

The blade is made of Persian crucible damascus steel and has a central fuller. The State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg attributes this shamshir to the 19 century and states that it is from the Winter Palace.

A straight sword šamšir-e mostāqim from the second half of the 19th century. It was acquired in 1926 from the Marble Palace. The handle is made of steel with downward quillons. For a detailed analysis of this types of swords see “Arms and Armor from Iran: The Bronze Age to the End of the Qajar Period” (Manouchehr Moshtagh Khorasani, 2006, Tübingen: Legat Verlag):

“Lebedynsky (1992:56) provides a brief analysis on Qajar straight swords. He states that the later straight swords (such as Qajar straight swords) share the same features as their medieval ancestors. These Iranian swords of the 17th and 18th century have blades with a rounded tip, downward quillions, and a three-lobe pommel and, thus, share the same feature of the grip as on some older swords”.

For more information on Iranian straight swords also see:

A 19 century ritual sword (šamšir-e mostāqim: straight sword) from Iran. It is from the Winter Palace.

For another article on Iranian straight swords see:

A 19 century ritual sword (šamšir-e mostāqim: straight sword) from Iran. It was acquired in 1931 and was formerly held in the collection of Count Sergey Sheremekev’s collection.