Prior to World War One (1914-1918; also known as the Great War) Iran lacked a single unified standing army capable of resisting military invasions, a situation that lasted until 1921.

When the Great War ended in 1918, Iran’s military situation was dire. There were now four distinct military forces, in which each acted according to different interests: (1) the Qajar government national army (2) the Persian Cossacks (3) the South Persia Rifles and (4) the Gendarmerie.

(1) The Qajar Government force. Nominally the “national army”, this was in fact a highly ineffective force. Military equipment (especially guns and cannon) were mostly outdated and of substandard quality. Iranian arsenals were also poorly managed. The last military acquisitions were Austrian artillery pieces that had been delivered to Iran in 1898 (negotiations for more purchases had been made in 1901). Iranian troops were still using obsolete percussion and matchlocks, but there were numbers of more modern Snider and Martini (single-shot breech-loading) rifles becoming available.

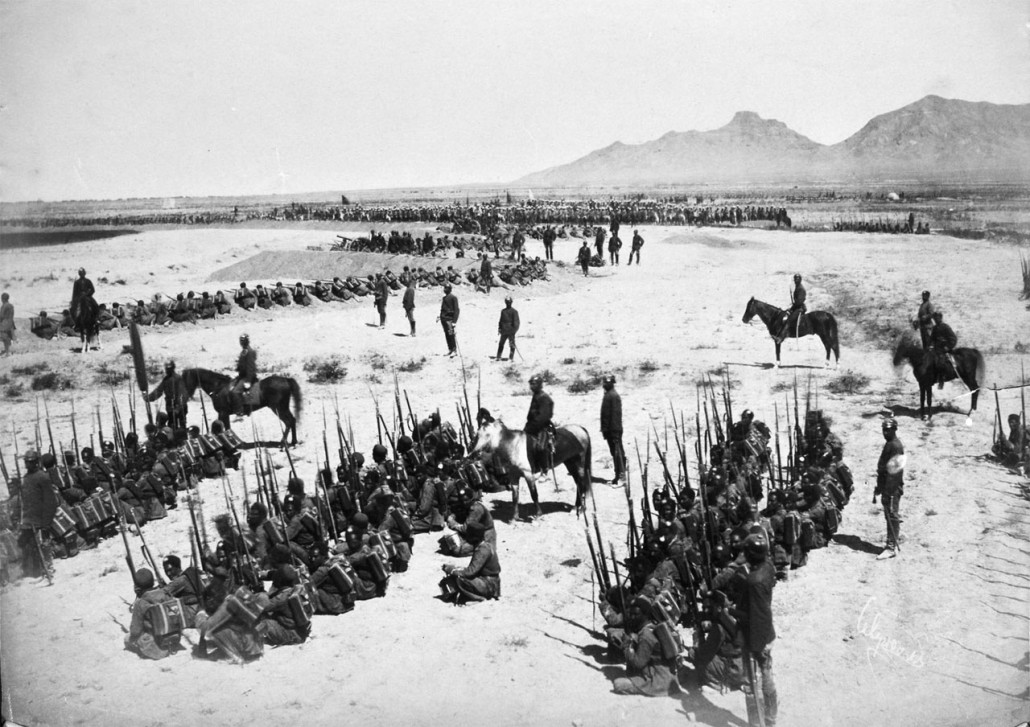

Very interesting photo of an assembly of Qajar troops prior to World War One; these troops show marked imperial German influence as seen by a number of troops wearing “Germanic” type helmets. The backpacks of the above troops resemble those worn by imperial German and Austro-Hungarian troops (Source: Russian Guns.Ru website).

Very interesting photo of an assembly of Qajar troops prior to World War One; these troops show marked imperial German influence as seen by a number of troops wearing “Germanic” type helmets. The backpacks of the above troops resemble those worn by imperial German and Austro-Hungarian troops (Source: Russian Guns.Ru website).

The Iranian military of the early 1900s was in a desperate state. While Iran had on paper a total of 150,000 troops at Mozzafar e Din Shah’s time, barely a fraction of such troops could be raised when World War One began in 1914. The few available troops were hardly effective as a fighting force. Farjollah Hosseini, the Chief Consul of Iran to England in the early 1900s summarized the desperate state of the Iranian military as follows:

“…the military office is nominally 70,000 men but is officially nil as numbers of our formations have never seen service…it would take six months to get our army to move if we were to mobilize available formations. We have no weapons, no ammunition reserves, no military schools…no military regulations, no factories and no battleships”

[Unit for the Publication of Documents-Office of International Political Studies, 1991, pp. 92]While Hosseini’s observations regarding military factories and schools were somewhat exaggerated, much of what he told the British was accurate. Many Iranian officers lacked knowledge of modern military doctrines, and most troops were poorly trained and disciplined, and morale was low.

A small Qajar army detachment prepares to march (Source: قشون نظامی ایران در زمان قاجار and Public Domain). Note the slovenly state of their appearance, such as boots, gear on belts (or lack of), unkempt uniforms (note person in the rear with oversized military coat). Due in large part to the Qajar administration’s mis-management, cronyism and corruption, the Iranian army by the early 20th century was poorly equipped and trained to defend the country’s borders against Russian, Ottoman and British (or British-Indian) intrusions.

By the onset of the First World War, the Qajar army had ceased to be an effective military force capable of combating and repelling invasions from modern and well-equipped foreign armies.

French postcard with photograph of a Qajar military band attired in red-blue uniforms (Source: Fouman).

A serious obstacle against serious military reform was corruption in just the militayr apparatus but the Qajar government and society as a whole. Put simply, corrupt officials in important posts (civilian and military) often placed their personal wealth, personal interests and status ahead of their country’s interests. As a result, regular army troops, conscripts and levies continued to suffer from arrears in pay. The army even failed to provide its troops with adequate food, housing and a whole host of other essential services. To make matters worse, these same troops would also often see their personal income pocketed by their corrupt officers. Forced to make ends meet, Iranian soldiers were thus forced to engage in low-level vocational services and odd-jobs in the civilian sector such as hard labour and gardening. All of this meant time taken away from regular military training and preparedness. All of this in turn translated to increasing anger and resentment among ordinary Iranian troops.

Shopkeepers at a bread outlet in a Tehran street in the early 20th century (Source: Poolnews.ir). Due to arrears in payments or outright theft of monthly payments by their superior Qajar officers, many regular troops had to find other jobs just to make ends meet.

The weaknesses of Qajar army forces allowed for foreign governments to invade Iran at will and to sponsor breakaway movements on Iranian soil.

Tribal levies normally support the central government but increasing Qajar weakness and disorganization in Tehran meant that recruiting these troops for the regular army became increasingly difficult. Thus, while these warriors remained effective in combatting (though not stemming) foreign invaders, tribal warriors became increasingly beholden to the security issues of their respective local provinces rather than the country as a whole.

(2) The Persian Cossack Brigade. This was first formed in 1879, with the arrival of Colonel Alexei Ivanovich Dumantovich to Tehran with a Cossack contingent. The Persian Cossacks were essentially modeled and trained by Imperial Russia. These were essentially under Russian command and served imperial Russian interests in Iran.

Elements of the Persian Cossack Brigade in Tehran sometime in the early 20th century, possibly in the 1910s prior to World War One; note the Persian sabres (Source: Russian Guns.Ru website).

The Persian Cossacks supported Czarist actions in suppressing the Constitutional Movement in Iran – notably the infamous bombing of Iran’s democratically elected Majlis (Parliament) by Colonel Vladimir Platonovitch Liakhov on June 23, 1908. The Persian Cossacks were finally disbanded on December 6, 1921.

(3) The South Persia Rifles (S.P.R.). This force had been formed by the British Empire by Fall 1916 on Iranian soil during World War One. Led mainly by British officers, the S.P.R. worked to safeguard British interests (for the main part) in southern Iran, notably the Persian Gulf coastline and the new oil industry in Khuzestan province.

Interesting photograph (1917?) of British and Iranian officers of the South Persia Rifles (S.P.R.) of Shiraz, under the command of Lieut.-Col. W. A. K. Fraser, M.C., of the Central India Horse (Source: The Illustrated First World War). Note the description in the above photograph which clearly outlines the S.P.R.s objectives: “Guarding Our Interests in the Land of the Shah: officers of the South Persian Rifles”.

The S.P.R. had first recruited approximately 8000 Iranians and Indians into its force. Units of the S.P.R. were then stationed in Fars, Kerman and Bandar Abbas. The S.P.R. proved critical in suppressing anti-British revolts in the south during the war. At its height, this force was to have a maximum size of 11,000 thousand troops. Many Iranian politicians opposed the S.P.R., noting that this force was the British version of the Persian Cossack Brigade. London had assured that the S.P.R. would be turned over to Iranian control after the conclusion of the First World War. The force was finally disbanded in October 1921.

(4) The Gendarmerie. The Iranian parliament had voted as early as 1910 to hire officers from neutral countries with Sweden soon chosen for the task. The Swedish mission led by Colonel H.O. Hjalmarsen arrived in Iran by May 1911 to quickly work towards building an indigenous Iranian gendarmerie. The mission proved successful.

The most effective force of the Iranian military prior to and during World war One: the Gendarmerie – above are Iranian Gendarmerie posing with two 75mm (Shneider-Cruesot?) in Tehran prior to World War One (Picture Source: Morgan Shuster, The Strangling of Persia, T. Fisher Unwin, London, 1913, pp. 144, 152). Despite being a para-military force, the Iranian Gendarmes fought very well against opponents who enjoyed superiority in numbers and military equipment. For more on the Iranian Gendarmerie, consult Stephanie Cronin’s article in the Encylopedia Iranica.

The Gendarmerie proved to be a highly motivated and relatively efficient force. These were the only forces loyal to the country and took no orders from Russia or Britain. They were however, a small force and despite their good training, lacked heavy weapons which prevented them from being able to repel foreign invasions.

Military Reform: Continuing Challenges until 1921

A serious problem for Iran was foreign, namely British and Russian interference: neither wished for Iran to have a strong, unified and modern national army. The British however, shifted their position, especially after the Bolsheviks overthrew the Czarist regime in Russia in 1917.

The Russians (Czarist and their Soviet successors) remained unfavourable to the notion of a modern, strong and militarily capable Iranian state. This is because if Iran were to possess a modern army, this would then be capable of repelling foreign invasions. Russia in particular was sensitive about this as it had conquered Iranian territory in the Caucasus and continued to harbour ambitions in not just northern Iran but all way towards the Persian Gulf. Despite having instituted a long-term and well-funded anti-Iranian cultural campaign in its conquered Caucasian territories, especially in the Arran-Shirvan region (Republic of Azerbaijan since May 1918), the Russians were deeply perturbed by the Caucasus’ historical ties with Iran. A reformed Iranian army and a strong national government in Tehran were seen as a threat by the Czarist regime in Moscow.

Map of Iran in 1805 before the territorial losses to Russia of the Caucasus and Central Asia. Iran also lost important eastern territories such as Herat which broke away with British support (Picture source: CAIS).

Following the end of the First World War, the importance of forming a unitary and modernized military was finally instituted. As noted previously, the disbanding of the pro-Russian Cossack brigade (now under British command following the overthrow of the Czars by the Bolsheviks in 1917) and the pro-British South Persia Rifles resulted in Iran finally having a unified national army, one of the chief aims of the Constitutional Movement of the Early Twentieth century.