The article below “The Battle of Carrhae, 53 B.C.” was originally written by Christopher Jones on the Gates of Nineveh website.

Kindly note that a number of images and accompanying captions inserted in the article version below do not appear in the original posting by Christopher Jones.

======================================================

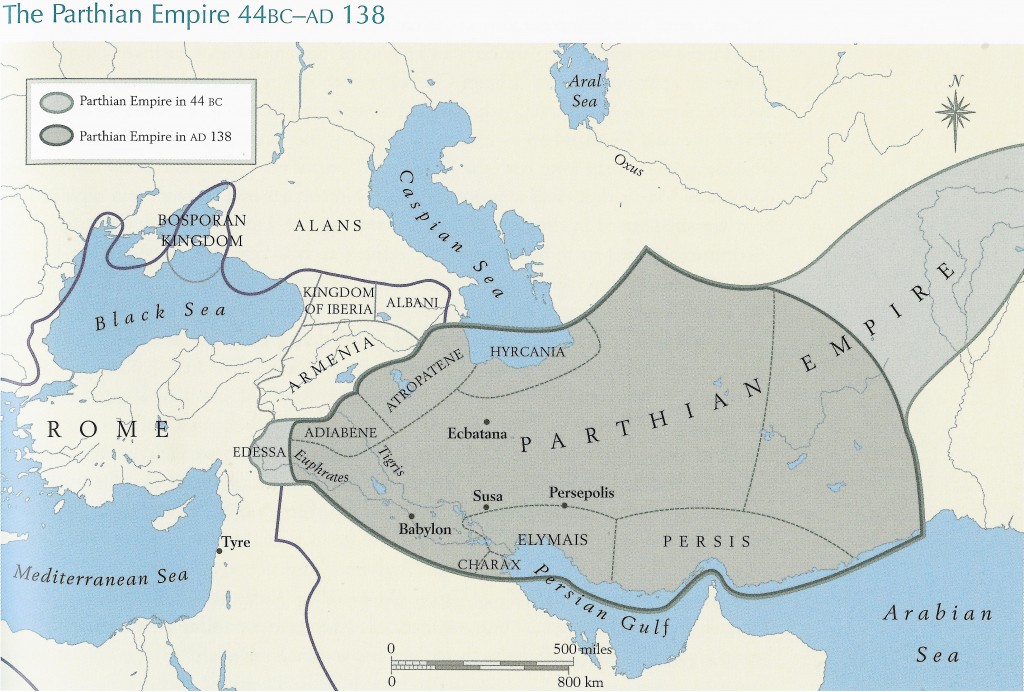

Scarcely had Alexander the Great destroyed the Persian Empire than it began to rise from the ashes. While most former Persian territory was under the control of the Seleucid Empire, in 247 BC, Shah Arsaces I founded the Arsacid Dynasty in Parthia. Parthia had been a minor outlying province in what is now northeastern Iran, but after much hard fighting they seized Iran from the Seleucids, and finally allied with the Roman general Pompey the Great to finish off the Seleucid Empire in 63 BC, leaving Parthia and Rome as the major powers in the Near East. Between them lay minor buffer states and client kingdoms.

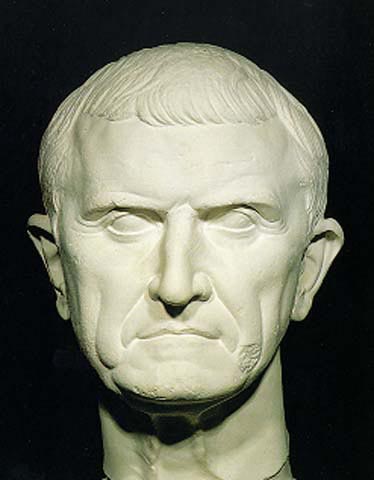

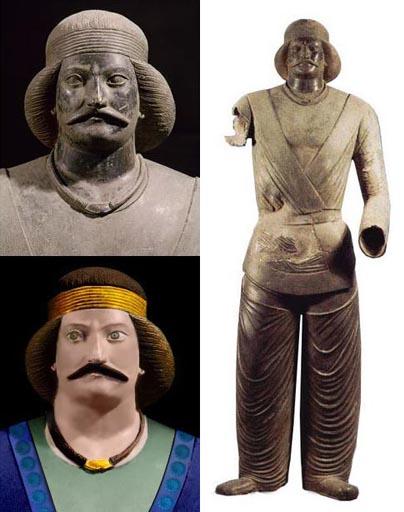

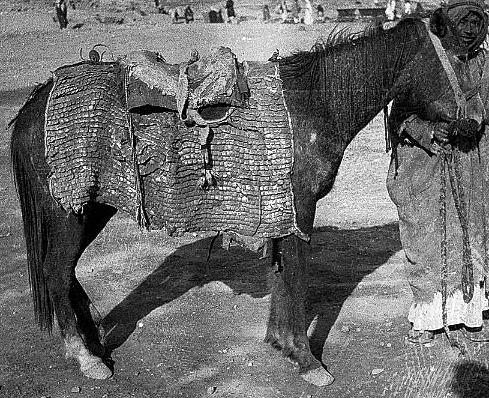

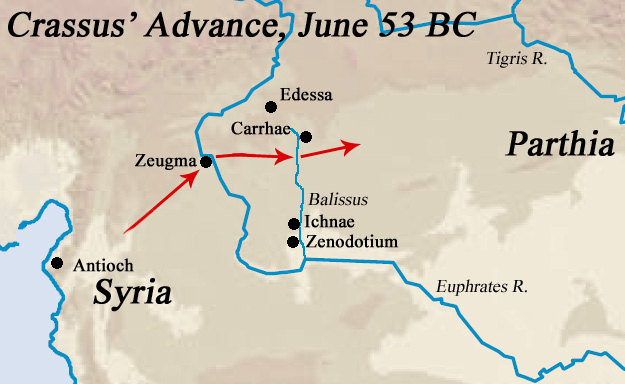

At this point, the two sides were at peace. The Parthian king Mithridates III wanted no further territorial expansion, and Rome had its hands full consolidating its newly acquired territory in the East and did not want trouble with another great power. Coin (front and reverse) of Parthian king Mithridates III (reign in c. 57-54 BCE) (Source: Classical Numismatic Group in Public Domain). Yet by the 50’s B.C., Rome’s internal political machinations spilled over into Parthia. In 59 BC, Julius Caesar, Pompey Magnus and Marcus Licinius Crassus formed a powerful but informal political alliance known as the First Triumvirate. Crassus and Pompey were both elected consuls in 55 BC after instigating mob violence against their opponents on election day. Their first acts were to extend Caesar’s term as governor of Gaul (which he was still in the process of conquering), and make themselves the governors of Spain and Syria once their term in office expired. They cast lots to see who would govern which territory. Pompey won Spain, and Crassus won Syria.[1] Marcus Licinius Crassus (c. 115-53 BCE) (Source: Gates of Nineveh). Crassus was fabulously wealthy, with a net worth in 54 B.C. of an estimated 7,100 talents or about $142 million. He made much of his fortune through seizing the property of those murdered in Sulla’s purges of 88 BC. Other sources of income included his ownership of silver mines as well as a profitable business in real estate development.[2] Crassus was fond of saying that no man was truly wealthy unless he could buy his own army.[3] Crassus was also brazenly ambitious. Plutarch would later condemn this as: “…foolish ambition, which would not let him rest satisfied to be first and greatest among many myriads of men, but made him think, because he was judged inferior to two men only, that he lacked everything.” After he was assigned the governorship of Syria, he immediately began laying plans for the conquest not only of Parthia, but of Bactria and India as well until Rome’s borders stretched all the way to the “Outer Sea.” Crassus was exceeding his authority here, as the law making him governor of Syria carried with it no authorization for war with Parthia. What’s more, his plans were highly unpopular with the Roman public. Many people viewed Crassus’ plan to launch an unprovoked surprise attack on a Roman ally who presented no immediate threat to Rome’s interests as both dishonorable and unwise. The anti-war faction was led by the tribune Ateius Capito, who tried to have Crassus arrested to prevent him from leaving Rome for Syria. He was dissuaded by the other nine tribunes, and had to content himself with placing a ritual curse on Crassus as he passed through the city gates.[4] In Parthia, on the other hand, in 54 BC Mithridates III was overthrown in a coup d’etat and fled from the capital of Ctesiphon across the river to Seleucia. His brother Orodes seized the throne and besieged Mithridates III in Seleucia with the aid of his brilliant general Surena, finally forcing the city’s surrender and seizing full control of the throne of Parthia. He was still in a shaky position, which led Crassus to think that victory would be easy and that many Parthian cities needed only a little prodding to revolt and side with Rome.[5] Lead-up to Battle – The Syrian Campaign of 54-53 BC Crassus arrived in Syria in 54 B.C. with seven legions. He immediately crossed the Euphrates River. The Parthians were taken completely by surprise, and Crassus easily defeated the Parthian forces under the command of the local satrap Silaces at Ichnae. Silaces himself barely escaped to Ctesiphon while dodging Roman cavalry patrols to warn Orodes of the invasion.[6] Parthian king Orodes II (reign 57-37 BCE) (Source: Gates of Nineveh). Most of the formerly Seleucid, Greek-inhabited cities in Parthian Syria were weary of oppressive Parthian feudal rule and were quick to switch sides and ally themselves with Crassus. The city of Zenodotium was an exception. The inhabitants asked for aid in revolting and received a detachment of 100 Roman troops. They then ambushed and killed these troops. As a result, Crassus sacked Zenodotium and sold its inhabitants as slaves. The other rebel cities received Roman garrisons for the winter to protect them from Parthian attempts to re-take their lost cities. In addition, the Arab king Abgar II of Osroene (whose capital was at Edessa) declared allegiance to Crassus.[7] Map of the general campaign geography (Source: Gates of Nineveh). Crassus spent the winter in Roman Syria preparing his forces for the coming spring. However, training and discipline began to slip as his forces remained in static garrison duty. He spent most of his energy trying to raise local levies, but was only able to raise 4,000 men before the spring campaign began. Sometimes, a bribe was enough to get him to let a city off the hook for providing troops.[8] Orodes responded to the invasion slowly. Parthia did not have a large standing army, so it took time for nobles to gather their forces for a major campaign. Orodes’ major concern was the possibility of Crassus making an alliance with Artabazes of Armenia and launching a two-front attack on Parthian territory. As a result, Orodes dispatched his chief subordinate and general Surenas to delay Crassus’ army in Syria, while he personally gathered an army to invade Armenia and keep Armenia from aiding Crassus.[9] Orodes’ fear was well founded, for that winter Artabazes arrived at Crassus’ headquarters with 6,000 cavalry. He promised that he could provide Crassus with 30,000 infantry and 16,000 cavalry for the upcoming campaign, effectively doubling Crassus’ force. Artabazes advised Crassus to advance through the mountains of southeastern Anatolia in order to avoid fighting the Parthian cavalry on a flat plain. Crassus declined, saying that he intended to march directly into Mesopotamia. Artabazes then decided to withdraw his forces from what was becoming apparent to him as a suicide mission, and returned to Armenia.[10] Parthian cavalry and banners (Picture source: Farrokh, page 130, Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War-Персы: Армия великих царей-سایههای صحرا– these drawings originally appeared by Zoka in the 2,500 Year Celebrations of the Persian Empire in 1971). Orodes then sent a peace delegation to Crassus. The delegates asked if he was invading Parthia with the full backing of the Roman people or on his own initiative. If he was invading on his own initiative, they would show mercy, but if it was with the backing of the Roman people they pledged total war “without truce and without treaty.” The very idea of asking such an odd question seems to indicate that Orodes was aware of Roman domestic opposition to the war and sought to give Crassus a way to make a face-saving exit from the conflict. Crassus replied that he would dictate his answer to the question after he captured Seleucia. Vagises, one of the Parthian envoys, pointed to his palm and replied “Crassus, hair will grow there before you see Seleucia.”[11] A reconstruction of the face on the statue of a Parthian nobleman housed at Tehran’s Iran Bastan Museum (Picture Source: Parthian Empire). In the meantime, Surena had been leading a winter campaign against those cities which had revolted and cast their lots in with Crassus. Some members of these garrisons fled to Crassus’ headquarters, bringing dreadful reports of the endurance and speed of the Parthian horse archers, the heavy armor of their cavalry and the armor-piercing capabilities of their arrows. Crassus does not seem to have significantly modified his plans based on this intelligence.[12] In June 53 BC, Crassus’ army set out towards the Euphrates. He crossed the Euphrates at Zeugma, in a violent thunderstorm which spooked some of the horses and caused them to run into the river. Wind blew some of the legion’s flags off a bridge and into the river. One of the bridges collapsed, dumping more men into the water. Many of his men viewed this as a bad omen of what was to come, and Crassus did not help matters by telling his troops not to worry, “for none of us shall come back this way.”[13] Opposing Forces Crassus left Rome with seven legions, which at full strength would have been about 33,040 combat troops and 37,240 men in total. However, he lost a number of men to shipwrecks in a storm while sailing from Italy. He also distributed 7,000 of his infantry on garrison duty in various Mesopotamian cities.[14] Therefore, it seems Crassus’ legions were not full strength. Assuming that he assigned non-combat support troops to garrison duty, he was departing Syria with at most 30,000 legionnaires. These men were almost all heavy infantry of one type, clothed with chain mail, a helmet and a large shield for protection and armed with a short sword called a gladius and several throwing javelins or pilum. The javelins had a long soft iron head designed to pierce armor, bend after impact and prevent them from being pulled out. What Roman troops lacked was any significant long range weapon for desert fighting. In addition, Crassus’ men were new recruits, who had not seen combat before. They were unfamiliar with eastern ways of fighting.[15] A modern re-enactor in the gear of a legionnaire of the late Roman Republic. The majority of Crassus’ troops would have looked like this (Source: Christopher Jones & Gates of Nineveh). In support of the legions, Crassus had 4,000 local infantry levies, including 500 archers. He also had 4,000 cavalry. 3,000 of these were local levies, and 1,000 were Gallic mercenaries. These Gauls were veterans of Julius Caesar’s campaigns and were the most battle-tested and experienced of Crassus’ troops. They were under the command of Crassus’ son Publius, himself a Gallic War veteran. The Gauls wore little armor and carried only short spears, putting them at a disadvantage against Parthian cavalry.[16] Publius was but one of numerous staff officers in Crassus’ army. Others included Gaius Cassius Longinus and Octavius. These officers provided Crassus with sound tactical advice, most of which he ignored. Crassus himself was sixty years old at the time of the Parthian campaign. He was fabulously wealthy and very powerful due to his wealth, but had never received a major military command. He had fought in Sulla’s army outside Rome and performed well, but his only campaign and only victory which he had been in supreme command was the suppression of Spartacus’ slave rebellion in 71 BC. It was partly a yearning for a military victory that sent him to the east.[17] The late exemplary actor Sir Laurence Olivier’s (1907-1989) portrayal of Marcus Lucinius Crassus (115-53 BCE) in the epic movie “Spartacus (1960)” (Picture Source: Murph Place). Crassus’ dreams of conquering Parthian Persia and emulating Alexander ended in disaster at Carrhae in 53 BCE. Several decades after its release of “Spartacus”, Hollywood has yet to produce a “Crassus sequel” epic of the Roman statesman’s failure in Persia. Crassus expected the war with Parthia to be similar to Pompey and Lucullus’ wars in the east against Pontus and Armenia. There, Roman heavy infantry had carried the day against numerically superior but lightly armed and armored forces. But this time Rome was heading to battle with an army of inexperienced soldiers led by an inexperienced commander, and would face new weapons and tactics against which they were unprepared.[18] Yet, despite all this, Crassus led his 38,000 men into battle against a Parthian force one quarter of his size. Parthia was a feudal-type monarchy, with the king at the top and satraps below him who ruled their own lands and were responsible for raising forces from their own territory for campaigns. Surena’s family estates were in the eastern part of the Parthian Empire. His army consisted entirely of cavalry, with no infantry at all. It is not known if this was all Surena had, or more likely, as Gareth Sampson has suggested, he modified his army based on what tactics he thought would best defeat the Romans.[19] Horse armor (Bargostvan) constructed of metal scales discovered at Dura Europus mounted on leather for a horse (Source: Stlcc.edu). The core of Surena’s army was made of horse archers. These men were serfs of the lands of their lord who were liable to be called up for military service. Despite this, they were highly trained archers who could attain a high rate of fire. Their bows were small, powerful and their arrows could pierce Roman chain mail. The dry air of summer made their bows even more effective. The men wore little to no armor, so in order to be effective they had to stay on flat ground and avoid fighting at close quarters. Parthian archers were infamous for the “Parthian Shot,” a maneuver in which they would charge an enemy force, then quickly turn and retreat. While galloping away, they would turn in the saddle and shoot their bows backwards over the horses’ hindquarters. The elite of Surena’s force were 1,000 chosen men called cataphracts. These were the noblemen and aristocrats of Parthian society, mounted warriors similar to a medieval European knight. Cataphracts wore heavy armor, including suit of chain mail and a helmet. Their horses also wore full suits of armor that hung down past their knees. The cataphracts carried long lances as their primary weapon.[20] The Parthian army traveled light. Each horseman rode with a number of spare horses. In addition, Surena brought up a baggage train of 1,000 camels carrying arrows to resupply his archers. Parthian armies’ lack of a robust supply chain limited their ability to wage offensive war for extended periods or to engage in siege warfare.[21] Relief showing a Parthian horse archer, Palazzo Madama museum, Turin, Italy (Source: Christopher Jones & Gates of Nineveh). In total, Surena had 10,000 men at his disposal, including support troops. Given the Parthian army’s light supply chain, it seems that his total number of combatants cannot have been much less than this number.[22] However, unlike Crassus, Surena was an experienced general. He served as Orodes’ main commander in the Parthian civil war of 54 BC, and brought victory with his successful siege of Seleucia.[23] His orders were simply to delay Crassus with his cavalry force until Orodes was finished with his Armenian campaign, but Surena set his sights on something bigger. Fighting on familiar territory, with a crack force of battle-hardened and highly trained troops at his command, he made plans for the annihilation of Crassus’ army. Battle Surena’s scouts kept a close eye on Crassus’ force after it crossed the Euphrates. Crassus’ cavalry scouts picked up on the tracks of the Parthian scouts soon after crossing the river. Realizing that the enemy was close, Cassius suggested moving the army within the walls of a friendly city until the scouts could gather more information about the location and numbers of the enemy. Crassus refused, arguing that they needed to press on.[24] Reconstruction by Peter Wilcox and the late historical artist, Angus McBride of Parthian armored knights as they would have appeared in 54 BCE (Source: Osprey Publishing). At this time, Abgar II of Osroene arrived with much needed information about Surena’s forces. Abgar II reported that a small Parthian force under Surena was nearby. This force, according to Abgar, was merely a delaying force designed to block Crassus’ advance long enough for Orodes to gather his main force. If Crassus moved quickly, he could scatter Surena’s force and seize a large section of Parthian territory before Orodes could bring his main army to bear. Strictly speaking, all of this information was true. But Abgar II was in fact acting as a Parthian agent, who was working for Surena to lure Crassus into a trap. Crassus’ previous plan had been to advance down the eastern bank of the Euphrates, capture Seleucia, and then cross the Tigris and attack the Parthian capital of Ctesiphon. This was not a bad plan, as the Tigris would protect Crassus’ left flank, the marshy ground between the two rivers would prevent Parthian cavalry from having easy room to maneuver, and the river would supply fresh water to the army during its long march. Abgar II instead pressed Crassus to make a quick strike at Surena’s army by marching away from the Euphrates directly into the desert. Eager to get into combat, Crassus changed his plans and ordered a march into the desert. Abgar II then left the camp and went to Surena’s headquarters. He told Crassus he was leaving to feed Surena false information, but the information that he gave Surena was that Crassus was walking directly into his trap.[25] Crassus’ troops soon hit heavy sand. There were no trees or water anywhere. While on the march, Crassus received a message from Artabazes that Armenia was being invaded by a large Parthian force and that he could send no aid, but requested that Crassus come to his aid. Crassus exploded into rage, accusing the Armenians of treason and promising vengeance once the campaign was over.[26] Crassus’ advance in June 53 BCE (Source: Christopher Jones & Gates of Nineveh). Surena prepared for his attack by setting an ambush for the Roman scouts. Parthian cavalry ambushed the scouts while they were ahead of the Roman force and killed most of them. The survivors who escaped rode back to report that the enemy was near. In response, Cassius recommended extending the lines as far as possible and positioning cavalry along the flanks to avoid being surrounded. Crassus took this advice, then changed the formation into a hollow square with 12 cohorts on each side and a cavalry detachment next to each cohort. As the Romans were facing a force that was entirely cavalry and could attack from any direction, forming a hollow square was again not the worst possible idea. Unlike a long line, it would prevent his men from being overrun by Parthian cavalry charges.[27] Shortly before midday, Crassus’ advancing square came to a stream called the Balissus, a tributary of the Euphrates. Here, his men could drink water. They ate a meal in the ranks, while Crassus’ officers advised building a camp for the night until they could gather more information about the enemy, while Publius argued that the enemy was close and they should move on. Crassus was swayed by Publius and ordered the men to cross the Balissus and move forward at an increased pace. Past the Balissus, Surena had arrayed his troops in an ambush formation. His horse archers formed a wide line to screen the Roman cavalry. Behind the horse archers were the cataphracts, who were wearing camouflage made from rags and animal skins to keep the sun from reflecting off their armor and giving away their position. As the Roman force advanced, the Parthians began to beat drums to signify the advance and terrify the inexperienced Roman troops.[28] As the drumroll grew to a din, the Parthian cataphracts threw off their camouflage and charged the Roman line. The Roman legionnaires responded by locking their shields together and standing their ground. Seeing that they could not break through the Roman’s square formation, the cataphracts pulled back at the last minute. The Battle of Carrhae by around noon (Source: Christopher Jones & Gates of Nineveh). The horse archers moved in to surround the square on all sides. The poured arrows into the mass of Roman troops who were so tightly packed that they “would not suffer an archer to miss even if he wished it.” Crassus ordered his cavalry and lightly armed auxiliaries to charge the horse archers, but the archers turned and galloped away, firing over the backs of their horses. The light troops were vulnerable to the cataphracts on open ground, so they could not move far away from the main force and had to return to the ranks.[29] At this point, Crassus thought that his men could wait out the arrow shower until the Parthian archers ran out of arrows and were forced to fight hand to hand. However, in the distance they could see the archers replenishing their supply of arrows from their camel train. At this point, Crassus gathered 1,300 cavalry, 8 cohorts of infantry and 500 auxiliary archers in one formation under the command of Publius Crassus and ordered them to charge the Parthian archers in attempt to close the distance between them and bring them to hand to hand combat. Parthian Horse archers engage the Roman legions of Marcus Lucinius Crassus at Carrhae in 53 BCE. Unlike the Achamenid-Greek wars where Achaemenid arrows were unable to penetrate Hellenic shields and armor, Parthian archery was now able to penetrate the armor and shields of their Roman opponents (Picture Source: Antony Karasulas & Angus McBride). The Parthians predictably fell back, drawing Publius’ force away from the main Roman force. Once they were a sufficient distance away, the main Parthian force fell on Publius’ men and surrounded them. Parthian cavalry galloped in a circle around the Roman force to purposely kick dust into the air so they could not see. They then began firing arrows into the mass of men. Many men had their shields pierced by arrows which wounded their arms and hands. Others were pinned to the ground by arrows through their feet. Parthian arrows were barbed, so they could not be removed without tearing backwards through the flesh and causing further injury. Publius’ charge during the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BCE (Christopher Jones & Gates of Nineveh). Publius led his Gallic cavalry in a desperate charge against the Parthian cataphracts and finally succeeded in closing in on them and forcing hand to hand combat. Even here, the Parthians held the advantage. The Gauls were used to fighting in the forests of Europe where long spears would have been unwieldy, so they carried short spears which were inferior to the long lances of Parthian cataphracts. As a result, they were outreached by the Parthians and many had their horses taken out from under them on the first charge. What’s more, their short spears had difficulty penetrating the cataphract’s heavy armor while the Gauls wore almost no armor themselves. The Gauls had to resort to grabbing the spears Parthian horsemen and then wrestling them off their horses. Others dismounted, dove to the ground and reached under the armored skirts of the Parthian horses to stab them in the belly. Publius fell wounded. The injury of their commander forced the Gauls to dismount and fall back to a small nearby hill, where they formed a shield wall. Here they were surrounded again by the ever-present Parthian horse archers. Heat and thirst took their toll on the Romans, especially the Gauls who were unused to desert conditions. Publius saw the situation was hopeless. He had been shot through the hand with an arrow and was unable to hold a sword, so he ordered his shield-bearer to kill him in order to avoid being captured. The other Roman officers also committed suicide. The remaining troops fought on until a Parthian cataphract charge broke their lines. The five hundred survivors surrendered.[30] Parthian Shiva-tir (Horse Archers) engaged in discharging their missiles (Source: Ancientbattles.com). While the main body of the Parthian force had been fighting Publius’ men, Crassus had moved his troops to sloping ground. The first messenger Publius sent to Crassus had been killed, the second told him Publius was doomed without relief. This news was confirmed when a Parthian cataphract rode into view with Publius’ severed head tied to the end of his spear. The ominous drum roll resume, and the Parthian archers returned. Battle of Carrhae in the afternoon (Source: Christopher Jones & Gates of Nineveh). With the Roman cavalry almost eliminated, the Parthian cataphracts edged closer to the Roman infantry, forcing them into a tighter and tighter circle. The Romans locked their sheilds into a testudo formation to protect against the arrows, but this left them vulnerable to the cataphracts, who charged and drove their lances into spaces between the shields, sometimes impaling multiple men at once. Some Romans broke ranks and ran to escape, but they were quickly cut down. The massive amount of dust kicked up by the Parthian horses limited visibility. Thirst and heat started to take their toll on some men, with some Romans dying of heatstroke in the ranks. The corpses began to pile up, preventing the Romans from getting sure footing, [31] Cassius Dio describes the final stages of the battle thus: “For if they decided to lock shields for the purpose of avoiding the arrows by the closeness of their array, the pikemen were upon them with a rush, striking down some, and at least scattering the others; and if they extended their ranks to avoid this, they would be struck with the arrows. Hereupon many died from fright at the very charge of the pikemen, and many perished hemmed in by the horsemen. Others were knocked over by the pikes or were carried off transfixed. The missiles falling thick upon them from all sides at once struck down many by a mortal blow, rendered many useless for battle, and caused distress to all. They flew into their eyes and pierced their hands and all the other parts of their body and, penetrating their armour, deprived them of their protection and compelled them to expose themselves to each new missile. Thus, while a man was guarding against arrows or pulling out one that had stuck fast he received more wounds, one after another. Consequently it was impracticable for them to move, and impracticable to remain at rest. Neither course afforded them safety but each was fraught with destruction, the one because it was out of their power, and the other because they were then more easily wounded”.[32] The coming of night saved the remaining Romans. The Parthians could not fight effectively in the dark as they could not precisely coordinate the movements that their fighting style demanded. They were almost out of arrows and many archers’ bows had snapped from excessive use. They fell back for the night and planned to resume the battle in the morning. The final stages of the Battle of Carrhae (Source: Gates of Nineveh). The Romans were left to wait in formation in the uncertain darkness. At this point Crassus seems to have suffered a complete mental breakdown and simply lay on the ground motionless. His surviving deputies Cassius and Octavius called the remaining officers together for a council, and took command. They decided to withdraw under cover of darkness before the Parthians could return. The men withdrew silently, leaving their wounded who could not walk behind so as not to slow down their flight. The first to reach safety were 300 cavalry under Ignatius, who reached Carrhae at around midnight, alerted the garrison commander to the disaster, and then proceeded to Zeugma. Coponius, the officer in command of the Carrhae garrison, ordered a relief force to be sent out to find the survivors.[33] The retreat was a disaster. Units became separated in the dark. Crassus reached the city after linking up with Coponius’ relief force, but daybreak found many men and walking wounded still straggling towards Carrhae. Some of the wounded left behind killed themselves to avoid captured. When the Parthians returned to the battlefield, they killed 4,000 of the Roman wounded who had been left behind, and then set off in pursuit of the stragglers. Four cohorts were surrounded on one hill and cut down, with only 20 men escaping to Carrhae. Many others were captured or killed on the plains.[34] Aftermath The survivors regrouped in Carrhae. Surena learned from local Arab scouts who had been with Crassus’ army (presumably Abgar’s men) that Crassus and Cassius were in Carrhae. Surena didn’t want them to escape nor did he want to besiege Carrhae, so he sent a messenger seeking a truce. Crassus wished to hold up in Carrhae on the forlorn hope that he would receive aid from the Armenians. Cassius and Octavius ignored him and began plotting to break during the next moonless night and return to Roman Syria. Crassus hired a local guide named Andromachus, who was in fact a Parthian double agent. He led Crassus’ men into a swamp near the Balissus. As a result, Crassus and four cohorts wandered in circles, losing precious hours. Daybreak found him straggling along a road towards the hills. Octavius had already reached the hills with 5,000 men. Ocatvius saw Crassus’ men struggling toward the hills at daybreak and led his men down to link up with Crassus.[35] A standoff ensued. Surena did not want to fight the Romans in the hills where his cavalry would be at a disadvantage. He knew the Romans could escape at night. He had some of his men stage a conversation near some Roman prisoners, saying that the Parthians did not wish a war with Rome and were ready to negotiate. The prisoners were then released, and returned to the Roman camp with their stories. Emissaries were then sent to the Romans offering a truce if Crassus withdrew all troops to the west side of the Euphrates. Crassus dithered indecisively for a while, but facing mutiny from his own men, he agreed to meet with Surena between the armies.[36] Surena and his staff rode out towards the Roman lines, but Crassus had no horse and walked. Surena called for a horse, and sent a number of his men to send the horse to Crassus. When Crassus was reluctant to get on the horse, the Parthian envoys picked him up and threw him on the horse’s back, and began to slap the horse to get it to run faster. Thinking that Crassus was being abducted, Crassus’ staff began fighting with the Parthian envoys. Octavius drew his sword and stabbed a Parthian envoy, and was then cut down from behind. Crassus was killed in the scuffle, and the rest of the Roman delegation fled back to the army. The identity of the person who killed Crassus was in dispute even in ancient times, so we can safely say that we don’t know who it was. It is not known if Surena’s offer of negotiations was genuine or a trick to capture Crassus. After Crassus’ death, the remaining men of the army scattered. Some surrendered to the Parthians, others fled to the hills. Some escaped to Syria or Armenia. Many of those that fled were hunted down by Surena’s Arab allies and captured or killed.[37] The Parthians poured molten gold down Crassus’ throat as a symbol of his greed that had caused them to invade his country. They then beheaded his corpse, and messengers brought his head to Orodes, who had just finished concluding peace with the Armenians. Surena had a prisoner dress up as a Crassus look-alike and held a triumphal procession in Seleucia with the prisoner on display.[38] Roman casualties for the entire campaign, according to Plutarch, ran to 20,000 dead and 10,000 captured, with only small groups of men escaping to Roman territory. Parthian casualties are unknown, but had to have been significantly less.[39] Legacy Cassius successfully escaped to Syria with some of the troops and took command of all Roman forces in the province. In the aftermath of the battle, a small Parthian force invaded Roman Syria and besieged Antioch. Cassius defeated the Parthians at Antioch, and then defeated them again at Antigonea. Learning the lessons of Carrhae, Cassius used small detachments of troops hidden in wooded areas to ambush Parthian forces. The Parthian commander was killed in this battle, ending the Parthian invasion. Cassius’ interim governorship came to an end quickly and he was replaced by Bibulus. A skilled politician, Bibulus sponsored an attempt by Orodes’ son Pacorus to depose his father, thereby igniting a Parthian civil war. Thus, the Roman-Parthian war triggered by Crassus ended in 50 BC. Conflict would continue sporadically over the next few decades. Julius Caesar’s planned invasion of Parthia was cut short by his assassination. Parthia invaded Syria again in 40 BC, hoping to take advantage of the Roman civil wars to seize Roman territory. They were defeated. Mark Antony’s invasion of Parthia in an attempt to avenge Crassus’ death in 37 BC met with a similar disaster. A formal peace treaty was finally signed in 20 BC. At this time, surviving Roman prisoners taken at Carrhae 33 years earlier were finally released and the captured standards of Crassus’ and Antony’s legions were returned.[40] In Rome, the death of Crassus had far reaching political effects. Crassus and his supporters had served as a politically moderate buffer between Pompey’s optimates and Julius Caesar’s populares. With Crassus out of the picture, the two were set on a collision course which within a few years would lead to civil war and the collapse of the Roman Republic. Cassius would be caught up in this as well, taking a lead role in the assassination plot against Julius Caesar. Surena did not live long. After celebrating his triumph in Seleucia, Surena had become too powerful. His reputation for military genius was eclipsing that of the king. Orodes began to view Surena as a potential threat to the throne, and had him murdered.[41] Crassus’ war of aggression against Parthia was a disaster. Seven Roman legions were lost, annihilated by a force a third of their size. How did such a defeat happen? The defeat was primarily a failure of leadership. Crassus was guilty of a long series of blunders as a commander, failing at politics, intelligence and tactics. Crassus’ campaign in the fall of 54 successfully exploited anti-Parthian sentiment amongst the Greek population. However, Crassus failed to consolidate these gains and did not get strong commitment from the local Greek population to supply troops for the coming campaign. He also failed to understand that the local Arab kingdoms, like Osroene and Commagene, did not share the Greek’s disdain for Parthian rule. This failure to distinguish the two proved fatal, and led to Crassus misplacing his trust in local leaders such as Abgar who were actually Parthian double agents. His reliance on local guides were were often double agents was compounded by his unfamiliarity with the terrain. In addition to his failure to understand the local culture and politics, Crassus suffered from a severe case of preparing to fight the last war. He expected fighting the Parthians to be similar to previous wars against Pontus and Armenia. He was prepared to fight large numbers of light infantry, not heavily armored cavalry and thousands of horse archers. His tactics, such as forming a square formation and locking shields, were standard for fighting cavalry in Europe but useless in the desert, where the cavalry had endless room to maneuver and surround the formation. In addition, the Romans were outclassed technologically. There is no cover to hide behind when fighting in the desert, hence slight technical differences such as the range of weapons and the strength of armor become very important. This has been true from Surena and Crassus’ day all the way to World War II and the Persian Gulf War. The desert magnifies technological advantages. Parthian archers outranged Roman weapons. Parthian armor was sturdier than Roman armor. Parthian lances could outreach Roman spears. Fighting in forests or hills might allow these deficiencies to be overcome using good tactics, but the desert allowed for no such strategies. In contrast, Surena received regular intelligence about Roman movements from a network of local Arab spies. His small force was well-trained, experienced and highly motivated. His intelligence service not only provided accurate information but planted false or misleading information in Crassus’ headquarters about his strength and movements. In summation, Crassus was marching blind, into unfamiliar territory, with inexperienced troops, against an enemy whose numbers and capabilities he knew nothing about. His enemy knew his numbers, his movements and was equipped with better weapons and armor. When the battle began, Surena showed much greater tactical imagination that Crassus. While Crassus made decisions strictly “by the book,” Surena was not afraid to throw out the rule book and come up with new tactics such as battlefield resupply of arrows. Once the big picture is seen, Surena’s victory in spite of being outnumbered should not be that surprising. In the history of desert warfare, time and time again smaller, mobile armies with better equipment and training have defeated larger armies made up primarily of infantry. This has been true from Carrhae, to Edessa in 259, to Sidi Barrani in 1940, to Medina Ridge in 1991. Desert warfare requires mobility, and mobility requires information and technology. Without these three things, an army in the desert is likely to be subject to annihilation. References: Image Source: (Header)http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/198804/main.street.of.eurasia.htm (body)http://www.boisestate.edu/courses/westciv/romanrev/17.shtml,http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Coin_of_Orodes_II_of_Parthia.jpg, all maps based on free educational maps from the Maps for Students Page at the Ancient World Mapping Center,http://www.cais-soas.com/CAIS/History/ashkanian/surena.htm,http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lorica_Hamata.jpg,http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:ParthianHorseman.jpg,http://www.iranchamber.com/history/parthians/parthian_army.php,http://www.moddb.com/groups/ancient-weapon-lovers-group/images/late-roman-republic