The article “Arthurian Legend and the Sarmatians (Part I)” was originally written by Periklis Deligiannis. Regarding the Iranian origin of the Sarmatians see: Oric Basirov: Origin of pre-Imperial Iranian Peoples … For more on North Iranian peoples see … Scythian and Sarmatian History … For more on the links between ancient Greater Iran or Persia (Eire-An) and Europa, consult the following: Eire-An and Europa … Part II of the below article will be posted in September 2020.

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

In AD 175 , the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius settled thousands of Sarmatian cavalry mercenaries in Britain. Two centuries later, the Western Roman Empire withdrew her troops from the island. It seems that the independent

”British kingdom” preserved its unity and coherence but soon after it was struck by the ruthless Anglo-Saxon invasion. The Sarmatians were now merged with the Celtic and Romano-Briton population, taking the lead in checking the barbarians. This Sarmatian presence in Britain consists probably the historical background of the legend of king Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table.

The Romans conquered modern England and Wales during the 1st century A.D. The tribes of Caledonia (Caledonii, Cornavii/Cornovii, Venicones etc.) which corresponds to the modern Scottish Highlands, remained independent. By the 4th century, her peoples had been incorporated into the tribal union of the Picts (Picti, Pictae). Their name meant the “painted ones” in Latin because of the ancient Celtic custom of tattooing which they maintained. In fact, they called themselves Cruthni. The Romans held Britannia for more than three centuries, but the Christianization and Latinization of its population were confined only to the cities and in a few Southeastern rural regions. The great majority of the population remained Celtic in language and in cults. Especially the rural populations were greatly influenced by the Christian heresy of Pelagianism. In the late 4th century AD, the original Roman province of Britannia was split into four provinces: Caesaresia Magna, Caesaresia Flavia, Britannia I and Britannia II. The tribes of Caledonia and Ireland were raiding the Romano-British territory for centuries.

The Irish were crossing the Irish Sea with their light vessels, the Celtic curraghs. The Caledonians-Picts were attacking the Romano-British population by land and sea, using the same type of ships. Caledonia and Britannia were separated by a “neutral zone” (buffer zone in fact) between Antoninus’ and Hadrian’s Walls, which is almost equivalent to the modern Scottish Lowlands. The limits of Caledonia (latter Pictland) followed roughly the modern ‘unofficial’ boundaries between the Highlands and the Lowlands of Scotland. The tribes of this buffer zone between Britannia and Caledonia (the Damnonii, the Selgovae et. al.) had lived for two decades of the 2nd century AD under direct Roman control that had reached Antoninus’ Wall (Vallum Antonini). When they revolted, the Romans evacuated this region and restored the line of their defense in Hadrian’s Wall (Vallum Adriani). Eventually the Romans made allied vassals (foederati) the tribes of Lowland Scotland, using them as a buffer zone against the Caledonians/Picts. However, their fidelity was always questionable and the gradual weakening of the Empire led them to raiding the Romano-British territory.

Scales of Sarmatian armor found near Hadrians wall (Source: Periklis Deligiannis). They probably belonged to Iazygae or Alan mercenaries of the Roman army.

In the 4th century, the Roman weakening brought about the increase of the barbarian attacks and the emergence of a new invader: the Anglo-Saxons. The term ‘Anglo-Saxons’ (or usually simply ‘Saxons’) is a modern conventional name for of group of Germanic and a few Slavic invaders in Britain, originating from modern northern Germany, Netherlands, Belgium and Jutland (Denmark). This tribal group/union included the Saxons (the more numerous of the group), Engles (in Germanic: Engeln, modern English), Frisians, Jutes (Geats, a Gothic tribal offshoot), Proto-Norwegians (Northwestern Scandinavians), Danes, Angrivarians, Brukteri (Boruktuari), Westphalians, Ostphalians, Franks, Thuringians, Wangrians and a few Slavs. The Anglo-Saxons were crossing the North Sea with long boats (predecessors of the Viking ships) and were attacking Britannia, looting and capturing its inhabitants.

The Roman armies and garrisons of Britain who faced the Irish, Picts and Saxons included in the 4th century AD: I. the force of the Duke of Britannia (Dux Britanniarum) which was based in Eboracum (capital of the Parisii tribe) protecting Northern Britain and Hadrian’s Wall. II. the force of the Comes Litoris Saxonici (Saxon Shore) which protected the southeastern British coasts against the Anglo-Saxons. III. The fast-moving force of the Comes Britanniarum (mainly cavalry), a reserve in order to repel any sudden barbaric raid on any British coast.

In the early 5th century, the Western Roman Empire was undergoing collapse. The Romans had begun to withdraw their troops from Britain since the 4th century, in order to check the barbarian pressure on the continental border of the Rhine. In AD 383, the Hispano-Roman general Maximus, governor of Britannia who coveted the throne of Ravenna, landed in Gaul with many troops. The legionaries that he withdrew were not replaced with new ones. The protection of Roman Britain was now uneconomic for the crumbling Empire. The departure of the Roman soldiers continued, and together with them departed a great part of the noble and wealthy castes, whose members had already understood that very soon Britannia would not be a safe place to live. Urban life had already been reduced significantly and the economy had been shrunk. In 407 AD, the Empire withdrew its last regular troops from the island, probably along with most imperial administrators and employees. The soldiers who remained were essentially some Romans and foreign mercenaries who had families with native women or other footholds on the island, and the few British auxiliaries who supported the legions. The same applies to the remaining imperial officers and employees.

A number of Latin-speaking Germanic soldiers called gentiles, descendants of old mercenaries of Rome, remained especially in Eastern Britain. They initially fought their Anglo-Saxon brethren, however it is possible that later many of them joined the invaders on the basis of their common Germanic ancestry. The well-known Gewisse are most likely such a case. Finally, many of the Sarmatian mercenaries (to whom we shall refer in detail below) remained in the island as well. After 407, Britain South of Hadrian’s Wall although was accounted for as part of the Roman world, became virtually independent. The rise of the barbarian raids and invasions after the Roman withdrawal, embarrassed the British leadership. Its members sent a message to the Roman emperor, with a request for military aid against the raiders (Gemitus Britannorum, “Groans of the Britons”, 410 AD). The emperor could do nothing, advising them to organize their own defense.

Despite the departure of the imperial army and administration from Britain, the Roman-style organized life went on. The shrunken Roman cities continued to exist, but the way of life, language, cults and other Roman/Latin elements were steadily giving ground to the regenerated Celtic ones. The remaining Romanized aristocracy of South-Eastern Britain undertook the organizing of the defense of this region against the Saxons. The stably Celtic in civilization nobility of the mountainous and hilly Western Britain undertook the repulse mainly of the Irish raiders. The remaining former commanders of the Roman guards of Hadrian’s Wall and the local nobles became the hereditary ruling class of the Northern Briton territories, mainly undertaking the repulse of the Picts.

Reenactment of a Saxon warlord by the Historical association Wulfheodenas (Source: Periklis Deligiannis). Until the 9th century AD, the marching Anglo-Saxons gradually conquered the greatest part of the former Roman territories in Britain.

Considering the ethno-cultural conditions, the Northern British rulers were in an intermediate situation between the ‘authentic Celts’ of the Western region and the Romano-Britons of the South-Eastern part of the island . It is probable that the three mentioned groups were in rivalry during the Roman period. However, the common external threat of the barbarians joined them.

The former Roman Britain was gradually divided into small autonomous Celtic or Romano-Celtic states, led by military leaders who tried to maintain unified the “British kingdom” as they perceived their common territory. An action of their unifying policy was the election of a warlord (Duke) as their supreme political and military leader, who led the war efforts against the invaders and prevented internal conflicts. In the medieval chronicles, the supreme leader is referred as the ‘Supreme Ruler’ of the island, but his original title or his military one was the Dux Bellorum. Probably this office was the continuity of the Roman office of the Dux Britanniarum.

The Britons resisted the barbaric invasions, led by a series of inspirational supreme leaders like Voteporix, Vortigern and especially the legendary Arthur. Under their leadership, they crashed the Picts and the Irish overthrowing the Irish colonies in Wales and Lowland Scotland, and managed to check the Anglo-Saxons. In 429, the Romano-Britons crashed a horde of Saxon and Pict invaders.

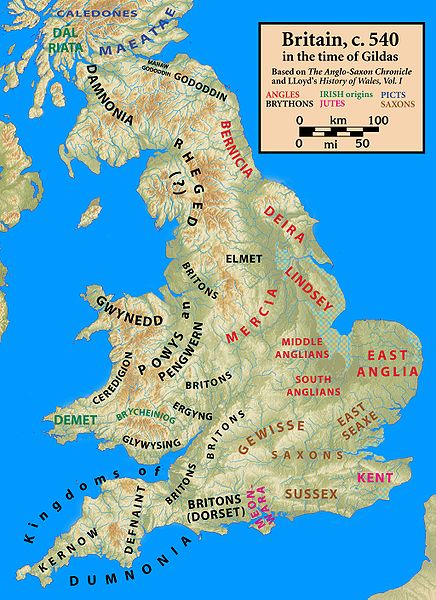

Map of Britain in c. 540 CE (Source: Periklis Deligiannis), contemporary to the Sassanians.

The British defense was successful until 442, when it was shaken by two fatal “scourges” (Gildas’ Chronicle). Vortigern, probably one of the leader of the Ordovices tribe of Wales, was at that time the Duke of Britannia (Supreme Ruler). His name is possibly not a personal name because it can be analyzed in Brythonic Celtic as the “Great King”, being probably a popularized rendering of the title Supreme Ruler. Vortigern had hired Jute mercenaries in order to repel the Anglo-Saxon invasions. Their rebellion (around 442 AD) against him was Gildas’ first “scourge”. The Jutes began to raid Eastern Britain, capturing or killing the inhabitants. The second “scourge” was a plague that occurred on the island (around 446) and mainly affected the urban centers, decimating the remaining Romanized population who lived primarily on them. It was a severe blow for the Romano-British administration and military organization, because they were staffed mainly by the Latinized population. In 446, the Romano-Britons asked for the military aid of the Roman general Aetius. The great Aetius (who was meant to repel Attila in 451 AD at the battle of Campus Mauriacus or Catalaunian Plains) was in Gaul. The Briton request was rejected again.

Vortigern’s preference to Germanic mercenaries was his great blunder. He probably did not trust the native officials and warriors, aiming on the consolidation of his power through the formation of his own “Praetorian guard” composed of Germans. He “fixed” his mistake of the recruitment of the Jutes with a bigger mistake: he settled a group of Saxon mercenaries under their warlords Horsa (‘the horse’) and Hengist (‘the stallion’), in the land of the Kantii (modern Kent) (about 450 AD). Their duty was to suppress the rebellion of the Jutes. The Saxons managed to defeat them but thereafter they also turned against Vortigern conducting atrocities and looting on the Britons, from their base at Kent. At the same time they called their brethren to come from their cradle in Northern Germany.

These newcomers landed on the shores of Britain and in a few decades they conquered the Southeastern part. But the Anglo-Saxon march was limited because of the efforts of the new Briton Duke (Supreme Ruler) Ambrosius Aurelianus and then it was stopped by the legendary great Duke Arthur. It has not been established yet whether Arthur was a mythological hero or a real historical personality, but the archaeological discoveries of the last decades and a review of the chronicles support his historicity. The literary, historical, archaeological and other relevant evidence suggests strongly that a powerful warlord did live during the verge of the 5th-6th centuries, uniting most of the Celtic and Romano-Briton tribes and states, and fending the invaders. He could not be other than Arthur of the Celto-British oral tradition and of the “History of the Kings of Britain” of Geoffrey of Monmouth (AD 1133).

Arthur as a military leader, was not depending on foreign mercenaries as Vortigern did, but in a “national” army comprised of Briton Celts, Romano-Britons, Romano-Germans and Romano-Sarmatians. He inflicted heavy losses to the Anglo-Saxons, forcing some of them to return disappointed in Germany as it is proved by archaeology.

The Roman army in Britain comprised many Sarmatian mercenaries, most of whom probably remained on the island after 407. The Sarmatians were a large group of nomadic tribes of Northern Iranian (Saka/Scythian) stock. Their cradle was in Central Asia, possibly in modern Northern Kazakhstan. Since the 3rd century B.C., some of their tribes started a migration to China, while the bulk of the people invaded gradually the modern Ukrainian steppes destroying the Scythian state in Europe. The various Sarmatian tribes were independent and very often were fighting each other. The most important were the Sauromatae, the Roxolani, the Iazygae, the Siraces, the ‘Royal Sarmatians’, the Aorsi/Alans, the Aspourgians etc.

The Sarmatians fought primarily as armored cavalry using a long and strong spear (the kontos) as their main weapon. The Romans of the Later Empire evaluated their martial spirit and recruited them massively as mercenaries. They ultimately adopted themselves the Sarmatian mounted warfare. The Goths, the Huns and other peoples did the same, and they also included in their ranks many Sarmatian allies. The formidable Sarmatians were dispersed and settled in many European regions, where they finally were assimilated by the local populations.

Emperor Julian is killed during his failed invasion of Sassanian Persia in June 26, 363 CE (Picture source: Farrokh, Plate D, Elite Sassanian cavalry, 2005). Above is a recreation of Sassanian Persia’s elite cavalry, the Savaran, as they would have appeared during Julian’s failed invasion. As noted by Periklis Deligiannis, the Sarmatian cataphracts belonged to a very similar type of cavalry as the Savaran. Sarmatian cataphracts were using armour made of large scales or mail armor like the Savaran in the above battle against Roman forces invading Sassanian Persia. Like the Sassanians, the Sarmatians also used helmets that were mainly of the spangenhelm type – see following article: Farrokh, K., Karamian, Gh., Kubic, A., & Oshterinani, M.T. (2017). An Examination of Parthian and Sasanian Military Helmets. In “Crowns, hats, turbans and helmets: Headgear in Iranian history volume I” (K. Maksymiuk & Gh. Karamian, Eds.), Siedlce University & Tehran Azad University, pp.121-163.

The Iazygae, a tribe of the Sarmatian vanguard, settled for some time in Pannonia (modern Hungarian and Croatian plain) and from there they were raiding the neighboring Roman territories. In AD 175, the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius defeated them and exiled 8,000 Iazygian horsemen (most of the surviving warriors of the tribe) in Gaul and Britain, where they were obliged to serve as mercenaries of the Roman army. 5,500 of them were settled in Britannia. The most important part of their story is that according to a honorific Roman tombstone, the commander of the Legio VI Victrix in which they enrolled, was an officer called Lucius Artorius Castus, who had served in Dalmatia (a region adjacent to Pannonia) and perhaps was of Dalmatian (Illyrian) origin. The enrollment of the Iazygian mercenaries in the Sixth Legion was not accidental. The Sarmatians undoubtedly welcomed a commander familiar to their homeland, possibly familiar with their customs and language as well. When their twenty-year term of office ended, the Romans forbade them to return to Pannonia resettling them in Bremetennacum (modern Ribchester, near Lancaster) and in two other sites in Britain. Later, these three Sarmatian settlements-sites were identified with three of the twelve sites of victories achieved by Arthur (Nennius: History of the Britons, late 8th century).

In the end of the 3rd century, a military unit of 500 Sarmatian cavalrymen is reported to be based in Bremetennacum, and they are considered to be the descendants of the Iazygian captives-mercenaries. The personal name Arthur comes possibly from a Celtic corruption of the Latin Artorius and it has been suggested that the legendary Arthur, Duke of Britain of the 5th-6th century, was a descendant of the Roman Artorius of the 2nd century. Another modern theory suggests that the Latin personal name Artorius became the Celtic title Arthur (like the Roman name Caesar was converted to the German title Kaiser and the Russian title Tsar). However, Arthur was undoubtedly a Celt, even if he was a distant descendant of the Roman Artorius.

The number of the Sarmatians in Britain was not inconsiderable. The Romans settled on the island 5,500 Iazygian warriors. The Sarmatians used to move with their families who lived in the typical heavy carriages of the nomads, thereby it is certain that many of the Iazygae settlers had their women and children with them. On the other hand, many would be young unmarried men who got married with Briton women. The usual ratio of combatants to non-combatants, used to calculate ancient populations, is 1:3 . Therefore, a ratio of 1:2 is acceptable for the Iazygae mercenaries in Britain and so we can assume a total figure of 16-17,000 with the women and children. If we add to them the rest of the Sarmatian mercenaries who settled in Britain, mainly Alans, the total Sarmatian population would number a few tens of thousands (possibly 20-30,000). The number of the Germanic gentiles in the island was higher. The total population of Britannia was around 1,000,000-1,500,000. It seems that the total figure of the Germanics and Sarmatians (men, women and children) did not exceed 5 % of the total population.

According to some modern scholars, the history of these Sarmatian mercenaries in Britain is the background of the Arthurian Legend, as we shall see in PART II (to be posted by Kavehfarrokh.com in September 2020).