What struck me about the movie was its portrayal of the Greco-Persian Wars in binary terms: the democratic, good, rational “Us” versus the tyrannical, evil and irrational, “other” of the ever-nebulous (if not exotic) “Persia“. Central to this dichotomy is the following message:

300 men stood between victory and the collapse of Western civilisation. … If the barbarian hordes … overran these defenders, Greek democracy and civilisation would fall prey to alien forces whose cruelty was a byword…

[Christopher Hudson, “The Greatest Warriors Ever“, Daily Mail, London, England, March 9, 2007]Note the key words “collapse of Western civilization“, “barbarian hordes“, “democracy and civilisation” and “alien forces whose cruelty was a byword“. These key words are reminiscent of political sloganeering, targeting the “other” with slanderous propaganda. These simplistic (and patronizing) statements are a clear indication that the general media and much of the audience is seeing “300” as much more than just a movie of a “graphic novel”. This has been astutely observed by Tomas Engle, a student at a West Virginia College, who has noted with some concern that many people are viewing the movie to “inform themselves on history.”

The citations from popular media outlets (such as The Daily Mail) are yet another vivid demonstration of the gross prevailing ignorance as to the actual origins of the notions of human rights, democracy and freedom, as well as the complex factors that led to the Greco-Persian wars.

The origins of democracy and human rights are not as simple as we are led to believe. As we will see below, these notions share both Greek and Iranian origins.

Meanwhile, the Greeks (the Athenians and their Ionian kin in particular), created the notion of Demos” (the people) and “Kratus” (government). This government by the people is what excites the imagination of the contemporary “western world“. However, few acknowledge the role of “the East” in helping place modern democracy as we know it today, within the context of racial, religious and cultural equality, or (more succinctly), human rights.

The founder of the Achaemenid Empire, Cyrus the Great, was the world’s first world emperor to openly declare and guarantee the sanctity of human rights and individual freedom.

Cyrus the Great as reconstructed by Tim Newark, 2000, p.21

(Ancient Armies, Concord Publications, painter Angus McBride)Cyrus was a follower of the teachings of Zoroaster (Zarathustra), the founder of one of the world’s oldest monotheistic religions.

Portrait of Zarathustra as depicted in a Mithraic Temple in Dura Europus (in modern Syria) in the 3rd Century AD.Zoroaster taught that good and evil resides in all members of humanity, regardless of racial origin, ethnic membership or religious affiliation. Each person is given the choice between good and evil – it is up to us to choose between them. It is that goodness, and a firm belief in its divinity, that is the key to human liberty, according to Zoroaster. As a consequence, every individual is entitled to liberty of thought, action and speech. This is enshrined in Zoroaster’s guidelines: Good Thoughts (Pendar Nik),Good Deeds (Kerdar Nik) and Good Speech (Goftar Nik).

As a result, freedom of thought, action and speech are laden with the awesome responsibility of wielding these for the good of all mankind. Zoroaster taught that there is no such thing as a “bad race” or “bad religion”. The only divide is that between good and bad people, both within one’s own community and those outside of one’s community. Zoroastrians often referred to ancient Iran as “the land of the Free/Freedom” (Zamin Azadegan).

Zoroaster preached the concept of an all-powerful single god known as Ahura-Mazda (the Supreme Angel), who stood for all that is good. However, the acceptance of Ahura-Mazda was a personal choice. There were to be no forced conversions and the gods of all nationalities were fully respected: Cyrus prostrated himself in front of the statue of Babylonian god Marduk after his conquest of Babylon. As noted by Graf, Hirsch, Gleason, & Krefter “Belief in a heavenly afterlife for good people and torment for evildoers may have been partly responsible for the moral treatment that Achaemenid Kings accorded subject nations … “

The Greek warrior-historian Xenophon, spoke highly of Cyrus in his Cyropaedia. Cyrus is described as being void of deceit, arrogance, guile or selfishness. Cyrus is the first “one world hero” in history, namely the ruler who sought to unite all the peoples into one empire while according full respect to all languages, creeds and religious practices. Alexander the Great, who greatly admired Cyrus, adopted his mantle of the “world hero” after his conquests of Persia in 333-323 BC.

Cyrus’ system of government has been forever immortalized by the Cyrus Cylinder. This is a clay cylinder of a decree that was issued by Cyrus the Great in 538 BC shortly after his conquest of Babylon.

The Cyrus Cylinder. This is the first human rights charter in history. A facsimile of the Cyrus Cylinder is present at the United Nations building in New York City.There three main premises in the decrees of the Cyrus Cylinder were:

(1) the institution of racial, linguistic and religious equality

(2) all exiled peoples were to be allowed to return home

(3) all destroyed temples were to be restored.

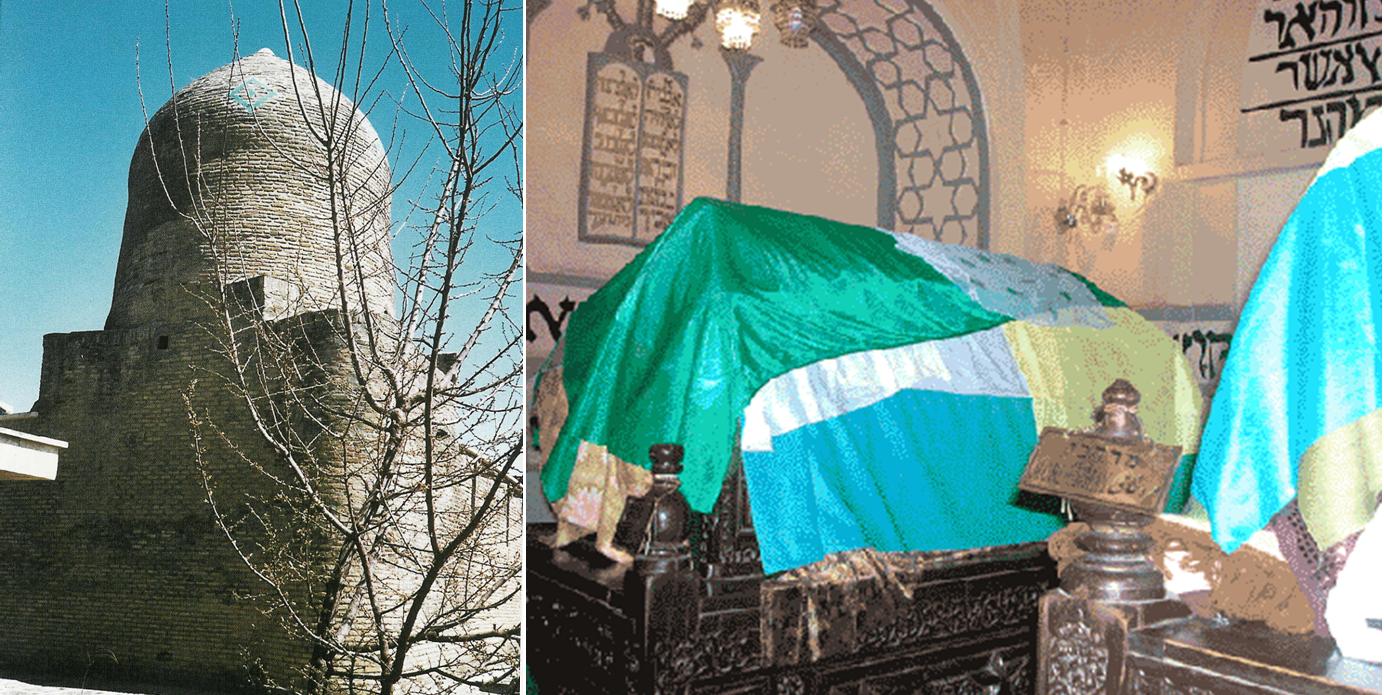

When Cyrus defeated King Nabonidus of Babylon, he officially declared the freedom of the Jews from their Babylonian captivity. This was the first time in history that a world power had guaranteed the survival of the Jewish people, religion, customs and culture. Cyrus allowed the Jews to rebuild their Temple and provided them with funds to do so. The empire continued that support as indicated by a decree by Darius the Great in 519-518 BC by allowing the Jews to complete the reconstruction of the Jerusalem Temple (Ezra, 4:1). Cyrus’ magnanimity is reflected in the Old Testament where he is cited as Yahweh’s anointed (See Book of Ezra 1). Koresh (Hebrew for Cyrus), was hailed as a Messiah by the Jews. Isaiah cites Cyrus as “He is my Shepherd, and he shall fulfill all my purpose” (Isaiah, 44.28; 45.1). The Biblical characters Ezra, Daniel, Esther and Mordecai played historically important roles in the Persian court. The tomb of Esther and Mordechai still stands to this day in Hamadan, the site of the ancient city of Ecbatana, a city that has hosted Jews for over 2500 years. The Persian king Xerxes himself was married to a Jewish queen named Esther.

A more humane 1962 Hollywood picture of ancient Iran

Xerxes (played by Richard Egan) and his Jewish queen Esther (played by Joan Collins)The tomb of Esther and Mordechai in Hamedan, northwest Iran. External view (left) and the interior of the tomb (right).

Professor Victor Davis Hanson (Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University, Professor emeritus at California University) summarizes the issue of “Freedom versus Tyranny” very succinctly:

If critics think that 300 reduces and simplifies the meaning of Thermopylae into freedom versus tyranny, they should reread carefully ancient accounts and then blame Herodotus, Plutarch, and Diodorus … who long ago boasted that Greek freedom was on trial against Persian autocracy … in almost all wars, one side is defending its freedom. The Greeks were not the first human beings to defend their freedom … monarchy is not something Eastern … when these ‘freedom-defender’ Greeks were united under Alexander, they did the same thing … they invaded Persia, Egypt and India and created their own empire … so did their Roman successors …” [For full text click here…} see: ]

Chapters:

- The Notion of Democracy and Human Rights

- What really led to War

- The Military Conflict: Separating Fact from Fiction

- The Error of Xerxes: The Burning of Athens

- The “West” battling against the “Mysticism” of “the East”

- The Portrayal of Iranians and Greeks

- A Note on the Iranian Women in Antiquity

- “Good” versus “Evil”

- Bibliography