The article below by Valeriya Nakshun has been reprinted with the permission of Bekhrad Joobin, the editor of the Reorientmag website.

==================================

Since the widespread Rachel Dolezal scandal, which involved an American woman claiming to be of African-American descent, discussions about cultural and ethnic appropriation have become increasingly heated and reconsidered. As controversial as the scandal may have been, it was certainly far from being anything new. There have been numerous cases throughout history where Europeans, for instance, have appropriated the cultures of others and misused them towards their own benefits and ambitions. When this occurs in relation to ‘Eastern’ peoples, it is often accompanied, one may argue, by a heavy dose of Saidian Orientalism. As a Jewish native of the Caucasus with an Eastern Mizrahi upbringing, at one stage in my life I became particularly interested in the life of Lev Nussimbaum, an Ashkenazi Jew from Eastern Europe who posed as an ‘exotic’ Muslim prince from Aran (renamed ‘Azerbaijan’ in 1918) and to have documented his adventures under the pseudonym ‘Essad Bey’, and later – according to American author Tom Reiss – ‘Kurban Said’. In his book, The Orientalist, Reiss examines Nussimbaum’s life, and how he shed his identity as a European Jew to become the famous Azerbaijani author. Under the pen name Kurban Said, Nussimbaum’s work (as per Reiss’ findings) became so popular that the love story, Ali and Nino (currently being made into a film by director Asif Kapadia), came to be revered as the national novel of Azerbaijan.

Lev? Essad? Kurban? (Source: Reorientmag).

Lev? Essad? Kurban? (Source: Reorientmag).

Raised in Baku, Nussimbaum traveled across the Caucasus, the Middle East, and Central Asia whilst fleeing the Bolsheviks with his father. Later, the pair emigrated to Germany, and it was there that Lev crafted his identity as Essad Bey and wrote several books about the exotic peoples he claimed to have encountered earlier on. With hostility and hatred towards Jews on the rise, Nussimbaum fled the Gestapo for America, where he continued with his writings. His works about the Caucasus, his childhood home of Azerbaijan, and Persia in some ways seemed to mirror the writings of William Walker Atkinson on India and South Asia. In a piece entitled American Orientalism, scholar and filmmaker Vivek Bald wrote about a former American lawyer and how he founded a publishing firm for books concerning Hinduism and spirituality. Like Nussimbaum, Atkinson wrote under several different Indian-sounding pseudonyms such as Yogi Ramacharaka, Swami Panchadasi, and others, in an effort to pander to European and American audiences. It has often been suggested that authors like Nussimbaum and Atikson exploited the Eastern traditions and cultures they wrote about for their own personal gain.

A Dagestani couple photographed in 1910 by Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky (Source: Reorientmag).

A Dagestani couple photographed in 1910 by Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky (Source: Reorientmag).

According to Bald, when ‘Oriental goods’ started making their way to the West, many Europeans and Americans (particularly the former) with colonial attitudes began to appropriate ‘conquered’ cultures and assert their dominance as superiors over the savage-yet-passionate Easterners. The undefined ‘Orient’ became a sort of monolith through which Europeans could fantasise about ideas that might not have been acceptable in their own societies. Images of harems, belly-dancers, and the like often transformed into fantastical and erotic escapes; and, because they so sexualised Eastern peoples, it was not considered inappropriate to view them as unintelligent, backwards, and lustful.

Lev Nussimbaum (1905-1942) in Caucasian attire. As noted by Valeriya Nakshun “It may be said that Nussimbaum, like others before and after him, assumed an ‘exotic’ identity in an escapist attempt to shed what he considered ‘boring’ or quotidian” (Source of Photo: RioWang Blogspot).

Lev Nussimbaum (1905-1942) in Caucasian attire. As noted by Valeriya Nakshun “It may be said that Nussimbaum, like others before and after him, assumed an ‘exotic’ identity in an escapist attempt to shed what he considered ‘boring’ or quotidian” (Source of Photo: RioWang Blogspot).

In many ways, it could be said that Nussimbaum’s view of the ‘East’ played out in more or less the same way. In his book, Twelve Secrets of the Caucasus, Essad Bey wrote about the various peoples inhabiting the region. Armenians, Azerbaijanis, Chechens, Georgians, Ossetians, Persians, and a host of others all provided rich subject matter for Nussimbaum. Written primarily for German readers, Nussimbaum often wrote about these peoples in a light many now might not deem particularly ‘rosy’, and painted them in many instances as a wild bunch with a penchant for swindling, beastly rituals, and savagery. Like Iran to its south, Azerbaijan, though predominantly Shi’a Muslim today, is a country with a strong history of Zoroastrianism (azar meaning ‘fire’ in Persian, and the name of the country referring to the Achaemenid satrap Atropates, ‘Protected by the Fire’). It is also known for its religious diversity, having been home to Eastern Christians and Jews for many centuries, if not millennia. According to Reiss, Nussimbaum was incredibly fascinated with Islam and the Arabic language, his infatuation leading him to ultimately convert officially in Berlin’s Turkish Embassy. It could be said, possibly, that his conversion had an influence on the author’s intentions with regard to his writings.

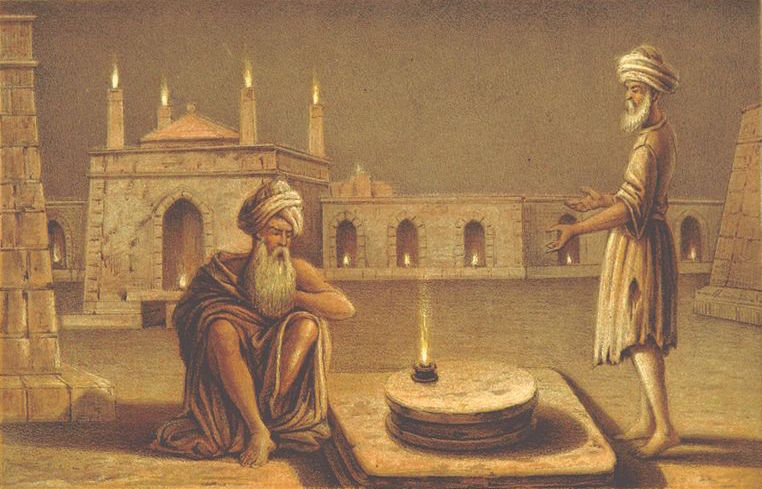

An illustration of Baku’s Zoroastrian fire temple (Pers. ‘atashgah’) from John Ussher’s 1865 travelogue, A Journey from London to Persepolis (Source: Reorientmag).

While Nussimbaum’s conversion might certainly have been genuine, it could be argued that it gave him a rather false sense of validity. To me, the most peculiar thing about the enigmatic author was his encounter (whether it actually occurred or not) with the indigenous Mizrahi Jews of the region – the same group that I belong to. We speak a Jewish dialect (Judeo-Tat) of Tati, an Iranian language closely related to Persian. Being a Jew, Nussimbaum’s writings on the Mizrahis of Dagestan and Azerbaijan should in theory, one could say, have been more familiar. However, it seems that Nussimbaum wrote even more harshly about them than any other group, as if in an attempt to distance himself from his origins and further emphasise his new identity. Such efforts may come as striking, as Azerbaijanis and other Muslims of the region lived in relative peace with members of other religious communities. Amongst other things, Nussimbaum wrote that the native Jews practiced strange blood rituals with their Muslim neighbours, and that their women washed the feet of men with their hair, both of which ‘observations’ have no historical basis or validity whatsoever. In a way, these sensual examples further evoke a sort of sexualised imagery about the practices of the region, far removed from its realities.

Two of Valeriya’s relatives in Derbent in the early 20th century (Source: Reorientmag).

Two of Valeriya’s relatives in Derbent in the early 20th century (Source: Reorientmag).

As Reiss posits in The Orientalist, Nussimbaum was at one point exposed as a fraud, and as such, had to change his pen name from Essad Bey to Kurban Said, such that he could regain some legitimacy for his writing. A sort of Orientalist Romeo and Juliet with similarities to other ‘Eastern’ romances such as the Persian Khosrow and Shirin (in which the Zoroastrian Sassanid monarch Khosrow falls for the Christian Armenian princess Shirin), Ali and Nino tells the story of Ali, an Azerbaijani Muslim man, and Nino, a Christian Georgian woman, set in Azerbaijan, Iran, and other nearby countries. Reiss’ assertion that Nussimbaum was Kurban Said cannot be taken for granted as a fact, as the relationship between the two is still being debated amongst scholars. Writers such as Betty Blair of Azerbaijan International, for example, are convinced that Kurban Said was in reality an Azerbaijani author by the name of Yusif Vazir Chamanzaminli – a view also held by many Azerbaijanis. However, due to what many have claimed to be Orientalist overtones throughout the novel, as well as the presence of hot-headed characters acting on their ‘Caucasian’ and ‘Asian’ emotions, their obsession with revenge, and Ali’s aggressiveness, others have rejected Blair’s argument and instead hold Nussimbaum to be the more likely author amongst the two.

An English translation of Kurban Said’s “Ali and Nino” (Source: Reorientmag).

An English translation of Kurban Said’s “Ali and Nino” (Source: Reorientmag).

Regardless of whether or not Nussimbaum was Kurban Said, his life as Essad Bey is nonetheless interesting. Overall, his Orientalist tendencies, it could be argued, seemingly came from some sort of self-loathing and the desire to belong (to a greater degree) to the region he was raised in. As a Jew in the early-mid 20th century, it makes sense that there may have been other reasons (e.g. anti-Jewish hatred and the pogroms) for his desire to reject his European or Jewish identity; but, if he simply wished to save himself from fascism, why were his writings so sensual, so egregiously incorrect and full of factual errors, and over-the-top with respect to the Orient? While the Jewish predicament certainly complicates the reasoning, it may be said that Nussimbaum, like others before and after him, assumed an ‘exotic’ identity in an escapist attempt to shed what he considered ‘boring’ or quotidian. Unfortunately, such newly-forged identities often turn out to be mere caricatures of those they strive to represent and their way of life.