The article below “A lasting Influence” was originally written by Muhammad Saleem Beig and posted on the Kashmir Life Website on March 25th, 2013.

According to Beig, Iran has made a deep mark on the cultural, demographic and political landscape through a certain amount of interactions which is visible in the old, vernacular houses, arts and crafts, and traditional shrines in Kashmir. Beig states that the historical narrative on Iranian influence has yet to do justice with its great impact and influence.

Beig is a former state government officer in India and head of the J&K Chapter of INTACH.

================================================================

Iran, from the second part of the first millennium, meant a geographic area comprising most of present day Central and Middle Asia stretching up to Afghanistan. In terms of culture and language, the Iranian influence was much beyond its geographical borders. Thus Iran was a culture, an influence, a historic resource and not necessarily a geographic entity. The historic links of Kashmir and Iran and the wider Persian speaking world has been immortalized by poet philosopher Iqbal who referred to it as Iran-i-Sagheer, the smaller or lesser Iran.

To a large extent, the culture of Kashmir bears a heavy imprint of Persian culture as well as an appreciation of arts, “moulded and refined” in the land of Iran. Though it seems highly plausible that a certain amount of cultural interaction between the two areas would have taken place even in ancient times especially during the Seculid period (200BC onwards), yet the enduring effect of Iran on Kashmir began with the establishment of the Sultanate rule in the 14th century. Henceforth, men of Iranian origin well versed in the arts, sciences and crafts of the medieval world embarked on an easterly route from their native land in Fars, Khurasan and Mawra-ul-Nahar into the valley of Kashmir. Some were drawn by a pious missionary zeal, some by a sense of travel and some by a promise of court patronage. Those emigrants included men of trade, of sword, of pen as well as governance.

Statue of King Kanishka I (c. AD 127–163) of the Kushan Empire (c. 30-375 CE) (housed in the Mathura Government Museum, Source: Public Domain). The large broadsword was a powerful cultural symbol in the martial cultures of the Iranian kingdoms as exemplified by the “broadsword” of Khosrow II seen at the top panel inside the Iwan at Taghe Bostan near Kermanshah in Western Iran. Note also the “French” Fleur-de-lis symbols at the bottom end of Kanishka’s shorter sword. The origins of the Fleur-de-lis are in the ancient Iranian realms and had a powerful imprint on the Caucasus, notably Georgia and Armenia.

It is in reign of Sultan Sikander in late 14th century (1393-1419 AD) that we witness the construction of the new Jamia Masjid under the supervision of Mir Sayyed Mohammed Hamdani, the illustrious son of Mir Syed Ali Hamdani, popularly known as Shah-e-Hamadan. The new Jamia was constructed on the pattern of the traditional courtyard plan with four iwans surrounding a central open courtyard. The four iwan plan which was introduced in the Islamic world in 11th century and is associated with the Seljuks, had by now become the most prominent and wide spread form of the Friday or Jamia mosque in Iran. Thereafter it remained as essential feature of what may be defined as the “Iranian mosque”, a form that did not remain confined to the land of its origin alone, but became an accepted model for areas as widespread and diverse as Transoxina and India.

The first four iwan mosque in India, the Begampur Friday mosque, had been constructed by the Tughlaqs at their capital Jehanpanah in 1343 AD, virtually around the same time when the Shahmiri sultanate was being set up in Kashmir. The adoption of this plan in Kashmir for the first time, which came nearly after a century of establishment of Muslim rule in the area, was complimented with the steady arrival of missionaries and artisans from the Persian speaking world. The design of the mosque is also reflective of the architects chosen, Sayyed Mohammed and Khawja Sadr-ud-din, both being Iranians. Traditional Kashmiri sources record the name of Sayyed Mohammed as Sayyed Mohammed Luristani, which would tend to indicate that he hailed from Luristan, a region in the south-west of Iran. His co-architect in the project, on the other hand, was from Khurasan, the vast and culturally rich eastern province of Iran. Together, the two men could be said to be drawn from two opposite ends of the land of Iran.

The Grand Mosque of Kashmir (known locally as “Jamia Masjid”) of the city of Srinagar, bears strong Persian architectural influences (Source: Photograph by Bilal Bahadur in Kashmirlife.net).

It is interesting to note that while the finest example of the iwan-courtyard mosque in Iran dating back to the Seljuk period, Masjid-i-Juma at Isfahan has a central courtyard measuring 196 x 230 feet, in comparison, the architects at Srinagar designed the mosque around an impressive central courtyard of 235 x 250 feet. While there is no implicit record of the desire to outsize the Isfahan mosque courtyard, yet the architects as well as their spiritual mentor, the Persian Sufi Mir Sayyed Mohammed Hamdani, must have been well aware of the fact that the Isfahan mosque comprised the largest courtyard mosque of Iran, their native land.

The desire to out build it could certainly have been there. In fact, the anonymous Kashmiri medieval historian of Baharistani Shahi, while recording the construction of the mosque, takes obvious pride in the size of his native mosque, “Throughout the lands of Hind and Sindh and the climes of Iran and Turan, one cannot come across a mosque of such grandeur and magnificence, though, of course, such grand mosques do exist in the lands of Egypt and Syria”

The ascent of Zain-ul-Abideen to the throne marks a new impetus towards promotion of arts and crafts. The architecture of this period follows two distinctly different traditions, a continuation of the indigenous system of wooden and masonry construction best exemplified by the mosque of Madni and a more “Iranian style” of masonry construction with domes and arches as seen at the Dumath. While continuing to patronize the local building traditions, the Sultan made a conscious endeavor to promote a sense of cultural unity with the rest of the Islamic world, especially the Persian world. This resulted in creation of buildings constructed to vie with the architectural monuments created, theoretically in any part of the Islamic land but essentially to the immediate west of Kashmir, especially Central Asia with its deep Iranian cultural imprints. The art of Kar-i-Kalamadan (Papier Machie), paper making, Khatamband, Pinjrakari, etc. all trace their origin to the Persian world. Even today, we find old, vernacular houses and traditional shrines which retain these architectural features, the dalan-from a similar element in the Iranian architecture known as Talar, the Varussi form the Persian word “Urussi” all point to the land of their origin.

The Shalimar Bagh (Garden) of Srinagar, Kashmir constructed in the Mughal-era Persian architectural style featuring fountains, canals, pools, patterned flower works, grasses, trees, etc. (Source:Tripadikberadik).

The fall of the Sultanate and the establishment of Mughal suzerainty in Kashmir helped in further deepening the Iranian traditions of Kashmir. The Mughal Empire was Timurid in its form; in fact, they took great pride in it and used to refer to their suzerainty as Salateen-i-Chugtaiai. Their system of governance and culture canvass was heavily dominated by the Iranian influence. Given the fact that Persian cultural had already made a deep mark on the cultural landscape of Kashmir, Kashmiris were received well and encountered deep appreciation at the Mughal court. These included Kashmir calligraphers like Mohammed Murad as well as theologians like Sheikh Yaqub Sarfi, musicians, painters and to the surprise of later historians, the men and women of sword.

Thus we have references of Kashmiri women armed guard serving as the protector of the royal seraglio (Haram) of the Mughal princesses. During the reign of Mughal emperors especially Shah Jehan, a number of Iranian poets settled down in Kashmir giving a fresh impetus to the literary arts in the area. The school of Mulla Mohsin Fani, Mirza Darab Joya, etc. trained a host of Kashmiri poets who found the favor of both the Mughal Subedars as well as occasionally the Emperors themselves. Unfortunately, as most of these poets were associated with ‘Sabak-i-Hindi’, they did not find much appreciation in Iran. On the other hand, a number of Kashmiri theologians have by their composition left a permanent mark on the religious sciences of the Persian speaking land as well as the wider Muslim world.

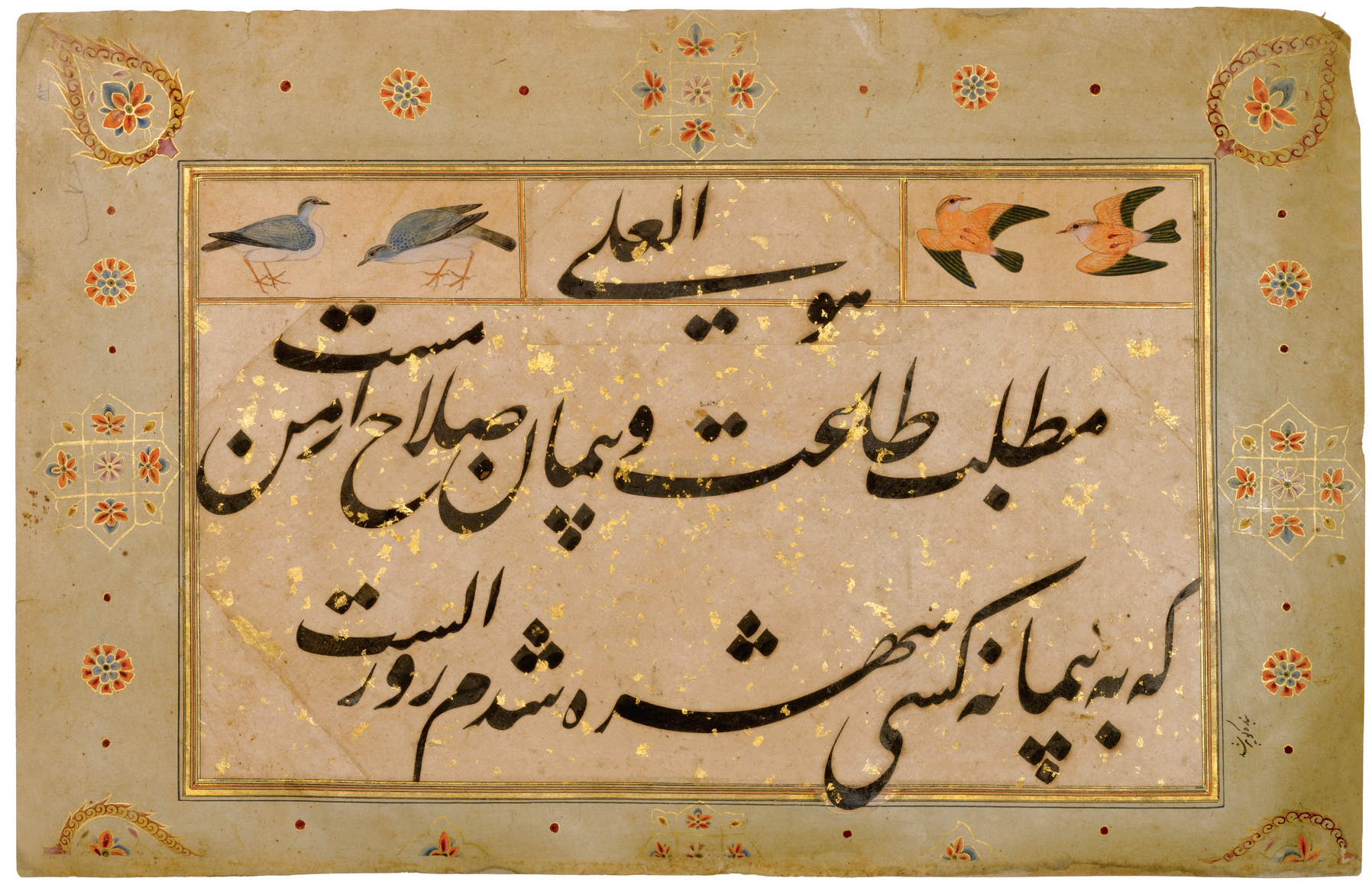

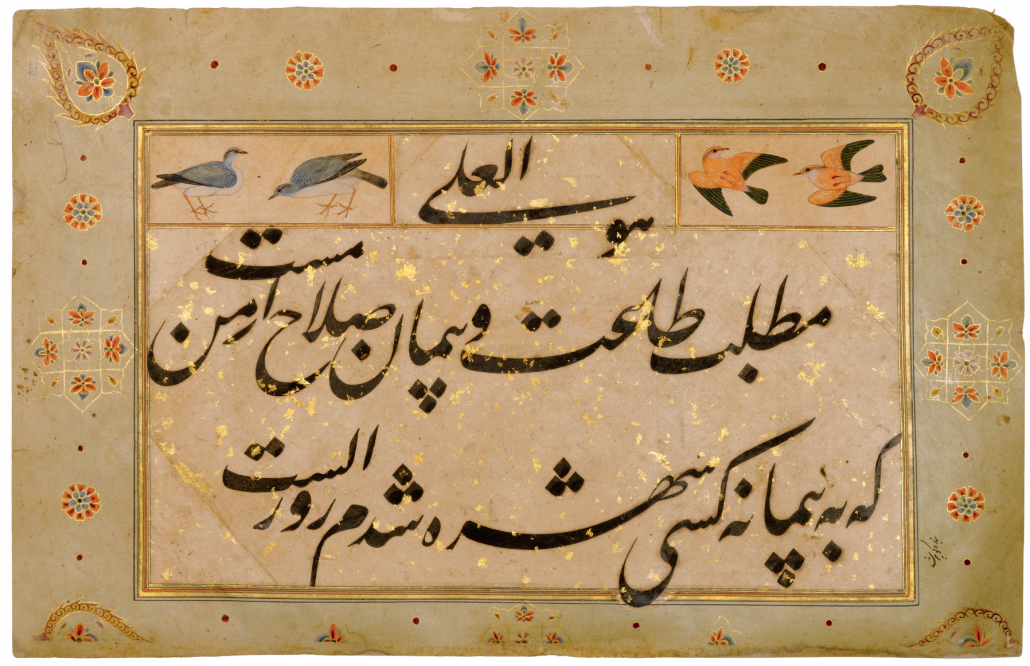

A Double-sided Persian calligraphy manuscript on paper by Zarin Qalam, signed by Faqir-i Kashmiri, India, Mughal, circa 1590-1600 (Source: Pinterest).

The Mughals also introduced the notion of “Paradise Gardens” into Kashmir, an idea highly indebted to Iran both in its concept and form. Though a large number of gardens had previously been constructed by the Sultans of Kashmir, yet the Mughals brought the concept to a sublime level of refinement. The historic narrative on Iranian influence has yet to do justice with the great impact and influence on onetime flowering of Kashmir as Iran-i-Sagheer. But then this is a tragedy of all narratives on Kashmir.