The article on Parthian horses and Parthian (horse) archers below was originally posted in Parthia.com and was written by Beverly Burris-Davis. Readers interested in the military history of Parthia may wish to click the picture below:

Before reading the article below, readers are referred to Pete Darmon’s most recent historical novel on the Parthians entitled Carrhae (for acquisition of this book consult Amazon):

================================================================

================================================================

When Arsaces I overthrew the Seleucid governor of Parthia and made himself king in 247 B.C., he set into motion a number of events that would literally change the world, providing he could keep Antiochus III from reclaiming his lost territories, territories conquered in the days of Alexander the Great. The Seleucids as a whole were not a pleasant people and antagonized many of their conquered subjects in the few hundred years that they ruled the Middle East. More interested in breeding war elephants than horses, they influenced the likes of Pyrrhus of Macedonia and Hannibal, who both overestimated the effectiveness of battle elephants in Europe.

The Parthians never took an interest in elephants and instead focused on the one successful means of warfare that worked, the cavalry. Alexander the Great’s cavalry was the decisive factor in many of his battles against the Persians and their allies. And the Scythians, the great horsemen of the Steppes, were responsible for more than their fair share of Persian casualties. Mounted archers on swift horses originally stolen from the Medes, the Scythians and their related tribes were responsible for the deaths and defeats of Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Persian Empire, and King Darius, who learned the hard way what a frog, arrow and bird represented to King Idymanthrus of Scythia.

The Parthians also adopted the Scythian bow, a double curve weapon ideal for horseback. The original Persian bow was a single curved weapon that was used by footmen. The Persians themselves seemed to prefer using spears when mounted since it did not require as much skill to kill a lion.

Single curve bow on silver tetradrachm of Artaxerxes III Ochus, ca. 333 B.C., 21.7 mm, 15.1 gm (Photo by permission Calgary Coin Gallery-Parthia.com).

One thing the Parthians did not adopt from the Scythians was their horse. The Scythians used several breeds of horse with the golden Akhal-Teke being their preferred mount. Their obsession with golden colored horses resulted in a large number of golden chestnuts and golden bays being found among the tribes and in the Scythian ice tombs. The Russian Don, now inhabiting the region once ruled by the Scythians, comes predominantly in golden chestnut and bay.

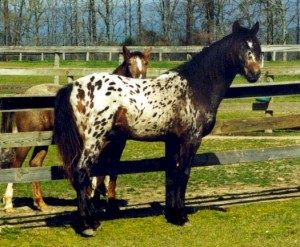

The Medes, a relative of the Parthians, raised this animal. But the Akhal-Teke, while possessing great endurance and some speed, was not as fast as the Parthians wanted. The Great Horse of the Persians was the mount they chose. A magnificent animal that came in all colors, including the highly desired palomino and appaloosa, was fast and strong and beautiful. He was also the ultimate riding horse, occasionally producing gaited animals that were highly sought after by everybody from China to Roman Spain.

During the reign of Mithradates II (c. 123 – 88 B.C.), one of the greatest kings of Parthia, Han Wu Ti (156-87 B.C.) of China was looking for an ally against the Xiongnu, a tribe of people who were raising general havoc in China. In 138 B.C., an envoy under the leadership of Zhang Qian was sent west to look for allies among the Yuezhi, a group of people who had once inhabited China. On his first outing Zhang Qian brought news back to the court of a people farther west, a people who raised a breed of horse that would be ideal for the Han cavalry. Sent out again, Zhang Qian suffered captured by the dreaded Xiongnu and didn’t get back home until 125, still without any horses. Determined, Han sent him out again and this time they reached the region of Ferghana, an area famous for its Akhal-Teke horses. According to The Chronicles of Three Kingdoms, Qian (sometime between 105-115 B.C.) found Parthian horses at Erhshih castle, which he had to lay siege to. When Qian eventually returned to China with a dozen Parthian horses and two thousand others, many of these Akhal-Teke types, Wu Ti was so impressed with the Parthian horses that he gave them the name of Heavenly Horses. Over the years, a legend grew up that these horses were descendents of dragons. In fact the Chinese name for the Parthian horse is Soulun, the vegetarian dragon. It was also claimed that the Soulun sweated blood, which may have been caused by a parasite, an interesting parasite that infected no other breed of horse.

Bronze tetrachalkous of Mithradates II (c. 123 – 88 B.C.), 21 mm, 6.6 gm (Photo by permission Doug Smith’s Ancient Greek & Roman Coins-Parthia.com).

Reproductions of the Heavenly Horse abound in China. One of the greatest painters was Han Gan of the later Tang dynasty, whose most famous painting is of a groom and two horses. The animals are spirited with strong necks and powerful haunches. Another artist from the Tang (618-906 A.D.) dynasty captured forever a beautiful palomino in ceramic. This very well could be the same horse immortalized on a Tang emperor’s tomb.

Han Gan, Tang Dynasty. Groom and Two Horses (Photo by permission-Parthia.com).

We do know that by 386 A.D. (Northern Wei Dynasty) the Chinese were riding Parthian horses and performing their own variation of the Parthian shot. A fresco on the ceiling of Cave 249, Chien-Fo-Tung shows a Chinese horseman using the traditional single curve bow against a lion like creature. The Asiatic lion, while now extinct in most of its former range, was once found from Eastern Europe to China. Hunting this great cat with horses goes as far back as the Assyrians who used chariots. With the arrival of the Great horse, lion hunts became more interesting. Mounted men would attack these magnificent cats with spears and bows, wiping out entire prides on a single hunt.

Northern Wei Dynasty. Fresco on Ceiling, Cave 249 (Photo by permission in Parthia.com).

But the loss of a dozen horses had no effect on Mithradates’ II reign, although the contact between his empire and China did create the Silk Road, one of the most important trade routes in ancient history. Silks and spices from China went west while horses and military styles went east. Even Yabusame, the Japanese form of archery on horseback, traces back to the Parthian archers, although the Japanese long bow has its traditions in Bushido, the way of the warrior.

Ceramic plaque of a mounted archer (British Museum, London (WA 1972-2-29,1 /135684), Photo by Chris Hopkins-Parthia.com).

Assuming the title King of Kings, an Old Persian title, Mithradates II stretched the Parthian empire to its farthest corners. He conquered Characene and recaptured Babylon and Mesopotamia from the Seleucids. He defeated the western Saka, a Scythian tribe related to the old Massagatae, freeing the empire from their depredations. An encounter between the Sakas and Parthians must have been a truly terrible fight, and one can only assume that the presence of the Parthian horse was the deciding factor in the outcome of the battle since both sides fought alike. They were both mounted horseman charging each other in the heat of battle, firing rapidly, deadly and effectively. Both the Sakas and Parthians used chain mail protection on their horses, and Parthian armor was very similar to Scythian armor with plaited rings laced together. The only major difference between the two combatants was the size of their horses. The Sakas on their sleek Akhal-Tekes or sturdy Mongolian-type ponies were a fierce determined people, but the Parthians on their stronger, faster horses were equally determined. The Parthian army proved itself superior to the Sakas, who never really threatened Parthia again.

In 96 B.C., during the reign Mithradates II, the Parthians came into contact with Rome, which was challenging the Seleucid dynasty for control of the Middle East. Seeking an ally against the Seleucids, Rome signed its first treaty with Parthia in 92 B.C., but Rome was an untrustworthy ally. Craving the old kingdom of Alexander the Great, it initiated several wars in the region, as war was a way for Romans to become famous, wealthy, and powerful. Pompey came to fame conquering Asia Minor and Syria in 64 B.C., while Julius Caesar fancied himself ruler of Rome after destroying the mighty Gauls and starting Rome’s campaign in Great Britain.

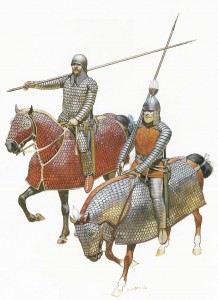

In 53 B.C., Marcus Licinius Crassus decided to add Parthia to the Roman Empire. His opponent was Surena, one of King Orodes’ II best generals. Surena was a student of Roman tactics and had trained his cavalry well. This cavalry was interesting in that it consisted of a heavy cavalry and a light cavalry. The heavy cavalry, the forerunner of the cataphract, wore steel armor and carried lances and swords. Chain mail protected the horses from their chests to their knees. A small animal would not have been able to carry this and a rider. The Romans had not seen the likes of it before. The light cavalry, on the other hand, was designed for speed with no heavy armor weighing the horses down. The Parthian archers, already gaining fame for their tactics, were ready.

Parthian Light Horse Cavalryman, Graffiti from private houses, Dura Europos. Earlier third century A.D. (After M. Rostovzeff, Caravan Cities, figs. 2 – Parthia.com).

Crassus could see the light cavalry, but Surena, who was personally commanding the cataphract, had his equine tanks in hiding. Galloping wildly, the Parthian light cavalry circled the Roman troops and fired ruthlessly into their ranks. Playing a suicidal waiting game, Crassus believed the Parthians would run out of arrows before he ran out of troops, but that was before he spotted Surena riding out of the woods with his heavy cavalry.

Foolishly Crassus sent his son with a 6,000 man mixed force of infantry and cavalry against Surena. Relying on an old Scytho-Parthian trick, Surena retreated, leading the younger Crassus away from the support of his father and the bulk of the Roman troops. At the precise moment, Surena wheeled about and attacked the surprised Romans, who broke before the onslaught of hoof, armor and lance. The Parthian light cavalry swarmed in and picked off the fleeing Romans, although legend says the younger Crassus had his shieldbearer kill him.

Crassus tried to save his troops by retreating to the city of Carrhae, where he stayed two days and organized his troops for a westward retreat. Leaving under the cover of darkness, hoping to avoid the Parthian cavalry, Crassus did not realize that Surena was keeping a close eye on him. The moment the Romans got into open, the Parthian light cavalry attacked. Crassus tried to mount a counter offense at sunrise but was unable to. The number of Roman dead was estimated at twenty thousand, among them Crassus whose head was presented to Orodes II as a war trophy, or so said Plutarch.

Julius Caesar at the time he was assassinated wanted to raise an army and go after the Parthians, who were proving themselves as difficult as the Germans to conquer. But it would be another 17 years before Caesar’s friend Marc Anthony mounted a campaign against the Parthians, who were in turmoil following the assassination of Orodes by his son Phraates. It didn’t hurt that King Artavasdes of Armenia also wanted a piece of the action and allied himself with Rome.

Parthian Heavy Horse Cavalryman Graffiti from private houses, Dura Europos. Earlier third century A.D. (After M. Rostovzeff, Caravan Cities, figs. 3 – Parthia.com).

In 36 B.C., Anthony ravaged the region of Media Atropatene with 16 legions. At his disposal were 100,000 infantry and 10,000 cavalry, most of these from Spain, a region famous for its proto-Arabian horses introduced into the region by the Phoenicians. He also had with him 30,000 shock troops made up of Roman allies who were unaware of Rome’s habit of sacrificing barbarians first in any attack.

Unwisely, Anthony separated himself from his baggage train and moved against Phraata, the capital of Media, which he hoped to take by storm. The Parthians inside refused to surrender, and Anthony began the arduous task of siege warfare. While he was trying to build a ramp to climb the city’s walls, Phraates attacked the baggage train, killing 10,000 men and destroying Anthony’s siege weapons.

Not one to give up, Anthony counterattacked in perfect Roman fashion. All straight and proper, the Romans marched on the Parthians in the field. So stunned by what they saw, the Parthians did not attack until the Romans initiated it with yells and screams. The Parthians gave ground and out ran the Roman cavalry, at a disadvantage on their smaller Iberian horses. When it was over, Anthony had won with 80 Parthians dead and 30 prisoners. Not much of a victory for this vain Roman. He returned to Phraata and found that his troops on guard there had abandoned the big mound of dirt that they had been building. To punish them, he killed every one in ten men left behind. Talk about a morale booster.

With his army on the verge of mutiny and the Parthian cavalry refusing to face the Romans outright, Anthony accepted Phraates’ offer to leave Parthia with his men under a flag of truce. As Anthony learned, the Parthians were not always to be trusted, but their little ambush fell through, and Anthony made it to Syria. The march was horrible for his men with a long month of climbing mountains and crossing rivers, while the Parthians harassed them the entire way and stole what goods they could get their hands on. This was the last major campaign that Rome mounted against the Parthians, and eventually Crassus’ captured eagles were returned to Rome as a sign of peace.

While all this warfare was going on a great Roman writer lived and documented the world around him. Strabo (63-24 B.C.) wrote that the Parthian horse using its Greek name, Niceaen, was the most elegant riding horse in the entire known world. Not a common sight in the Roman Empire until the Byzantine era, the Niceaens were given as gifts to various Roman emperors.

Influences

After Ardashir I (224-241 A.D.) overthrew Artabanus V and founded the Sasanian Empire, the Parthian/Niceaen horse fell into Persian hands, along with the Parthian concept of heavy and light cavalry. At its best, the Sasanian heavy cavalry was a mass of efficient chain mail. This may sound like an exaggeration, but the Persian cataphract consisted of a man completely covered in chain mail with only his eyes visible. The face, neck and forequarters of the horse were covered with links of plate metal laced together. Only a strong horse could carry this much weight and still perform the acts necessary of a good war-horse. The Parthian horse had been bred to be fast and strong, and these traits were still favored by the Sasanians.

The Roman emperor Valerian in A.D. 259 learned the hard way at Edessa to leave the Sasanian clibanarius alone when 70,000 men perished before the heavy cavalry of Shapur I, the son of Ardashir. A rock relief from the tomb of Darius at Naqsh-e-Rostam shows Emperor Valerian and one of his allies kneeling before Shapur I on a magnificent Parthian stallion.

Victory of Shapur I over Rome, third century A.D., Naqsh-e-Rostam, Iran-Parthia.com.

Strabo called the Parthian the most elegant riding horse in the Roman Empire, he was fast enough to beat Spanish horses that were reputed to be the fastest up until that time, and he was strong enough to be the backbone of the cataphract. In addition to this, the Parthian horse was beautiful. Artwork of him from China shows a proud elegant animal, and when Emperor Justinian introduced them to the Spain during the Visigoth Wars, the Parthian horse became the rootstock for the Andalusian and Lusitano. These horses in turn were ancestors to the American Quarterhorse, Appaloosa and Tigerhorse. The use of Spanish racehorses to improve English racehorses prior to the immortal three would also lead this author to believe that the size and strength of the Thoroughbred comes from his Parthian ancestors, not the small desert breeds the English hold in such high esteem.

Detail, sarcophagus of the “Triclinium of Maqqai”, c. A.D. 229, Palmyra, Syria-Parthia.com.

The Crusaders also dispersed Byzantine bred Parthian horses throughout Europe, in particular the Normans who destroyed the imperial stud when they sacked Constantinople. Horses were taken to France and Italy, which used the Parthian horse to create the now extinct Neapolitan breed. The Neapolitan had an enormous influence on the Lippizaner, giving the stallions a stronger build and more masculine appearance. It might also be said that the arts that these beautiful animals perform have their roots in the ancient empires of Persia and Parthia. The Greeks wrote about dressage, but it was the Parthian horse that performed it, and whether you call him Niceaen, Soulun, Heavenly Horse or Parthian horse, the loss of this great breed was a tragedy.

Annadale’s Love Story, a Tiger Horse stallion. Photo by permission, The Tiger Horse Registry-Parthia.com.

Bibliography

Altimira, Rafael (trans. By Muna Lee). A History of Spain (Toronto: D. Van Co., 1949)

Arribas, Antonio. The Iberians. (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1963)

Arberry, A. J. The Legacy Of Persia. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1953/1963)

Browning, Robert. Justinian and Theodora (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1971)

Culican, William. The Medes and Persians. (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1965)

Forte, Nancy. The Warrior in Art. (Minneapolis, MN: Lerner Pub., 1966)

Haussig, H. W. (trans. by J. W. Hussey). A History Of The Byzantine Civilization. (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1966/1971)

Hopkins, Edward C. D. The Parthian Empire (web site)

McNulty, Henry. “The Horses of Jerez”, Gourmet, June 1983

Ogata, Osamu. The Origins of “Yabusame” (Horseback Archery), 10 Jan 95 (web page)

Payne, Robert. “The Parthians” in The Splendor of Persia. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1957)

Rice, Tamara Talbot. The Scythians. (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1957)

Roux, Georges. Ancient Iraq. (New York: The World Pub. Co., 1964)

Varley, Victoria. President, The Tiger Horse Registry (web site)

Wild, Oliver. The Silk Road (web page)

Yabusame, or Japanese horseback archery (web page)

Zuelke, Ruth. The Horse In Art. (Minneapolis, MN: Lerner Pub., 1965)