The article “The Middle East”: A 20th Century Neologism that has Run its Time?” on the OpEd News outlet was originally written by Dr Mohammad Ala (winner of The Grand Prix Film Italia Award in 2013, The Panda Award in 2018, The Cinema Vérité Award in 2018 and The World Wildlife Award in 2019. Kindly note that the images and accompanying captions inserted below do not appear in the original article on Op Ed News.

==================================================================

Neologisms, according to Merriam-Webster, are new words or terms that are coined to express concepts that appear to lack a word or name. ‘Scuba’, “programming,” “subprime” and even “Nazi” are all examples of neologisms that were coined to refer to new activities, jobs and concepts that arose in the last century. In contrast, malapropisms are also new coinings of words but they are misuses of terms because they are not true representation of the concepts to which they refer. They are not really innovative or even correct, although they may sound right. Trumps use of ‘unpresidented” when he meant “unprecedented” ( see Brenden Berry, 2016 ) is an example, as is George W. Bush’s use of “misunderestimated” when he really meant either misestimated” or “underestimated”. (See reference # 5 below)

The term “Middle East” might seem to be just another creative neologism from the last century, but in my view it is also a malapropism. Rather than reflecting a true geographic region of the West Asia this term falsely groups countries and oversteps history, misleading people as to the true history, culture and languages of many countries with diverse population. The world does better without the use of “Middle East”, in my opinion.

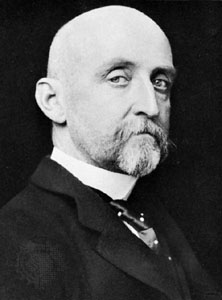

In practice, the expression “Middle East” has created many misconceptions about regional people, arts, and customs that disadvantage the many different peoples living in what is not necessarily a uniform part of the world. The history of the expression was recently documented in the Persian Heritage journal (2017, pp. 12-14) by Kaveh Farrokh and Sheda Vasseghi, who cited when and by whom the term Middle East was invented in the 20thcentury. They attribute its creation to Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840-1914) who invented the expression in the September 1902 issue of London’s monthly National Review, in an article entitled “The Persian Gulf and International Relations.” In that article Mahan wrote “the term Middle East, if I may adopt which I have not seen”. He may not have seen it in his day, but we have seen it far too often, in my opinion, and it is a disservice to continue using it.

The term “Middle East” was first invented by Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840-1914). Mahan’s invention first appeared in the September 1902 issue of London’s monthly “National review” in an article entitled “The Persian Gulf and International Relations”. Specifically, Mahan wrote: “The Middle East, if I may adopt the term which I have not seen…”. The term – “Middle East” – when examined in cultural, anthropological and cultural terms makes very little sense. Iran and Turkey for example are not Arab countries and in fact share a long-standing Turco-Iranian or Persianate civilization distinct from the Arabo-Islamic dynamic. Instead, the Turks and Iranians have strong ties to the Caucasus and Central Asia (Image: Encyclopedia Brittanica).

The term “Middle East” was first invented by Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840-1914). Mahan’s invention first appeared in the September 1902 issue of London’s monthly “National review” in an article entitled “The Persian Gulf and International Relations”. Specifically, Mahan wrote: “The Middle East, if I may adopt the term which I have not seen…”. The term – “Middle East” – when examined in cultural, anthropological and cultural terms makes very little sense. Iran and Turkey for example are not Arab countries and in fact share a long-standing Turco-Iranian or Persianate civilization distinct from the Arabo-Islamic dynamic. Instead, the Turks and Iranians have strong ties to the Caucasus and Central Asia (Image: Encyclopedia Brittanica).

Closer examination of this invented ‘term’ reveals that it has no linguistic, cultural, anthropological or historical substance. For example, Iran and most part of Turkey are not Arab countries but since they are included in the ‘Middle East’ they are often inferred to be “Arab'”. These regions share a long heritage of Turco-Iranian or Persianate civilization. A Persian influence in the region is evident in words which many languages use and in the region. Iranians and Turks have strong connection to the Caucasus. But what connections do these countries share with other ‘Arab’ states? Not culture, art, tradition and perspective so much as a geopolitical purpose for the “West”.

The power of the invented term “Middle East” and the argument that it is a malapropism both lie in the fact that it provided a new geopolitical terminology to a rather ad hoc portion of the world, just like the governor of Massachusetts, Gerry, reconfigured the districts in Massachusetts to benefit the Democratic Party in 1812. Governor Gerry was caught and hence the name “gerrymandering” to describe the practice intended to establish a political advantage for a particular group by manipulating boundaries. The “Middle East” is a form of gerrymandering: By calling attention to itself as an entity it dictates that there exists a defined region of the world which just happens to coincide with portions of West Asia where Western political, military, and economic interests are at stake. The term reconfigures “West Asia”, especially in the Persian Gulf region. It is gerrymandering, but like a malapropism, sounds convincing at least at first glance.

Propagation of “Middle East” was rapid in the first half of the 20th century. The term invented by Mahan was almost immediately popularized by Sir Ignatius Valentine Chirol (1852 — 1929), a journalist designed as a special correspondent from Tehran, Iran by the Times newspaper. Chirol’s article entitled, “the Middle Eastern Question,” expanded Mahan’s version of the “Middle East,” to new territories including Afghanistan and even Tibet. The situation gets funnier when the same or similar authors discuss the Islamic arts and architecture.

Mahan’s invented term “Middle East” was popularized by Sir Ignatius Valentine Chirol (1852-1929), a journalist designated as “a special correspondent from Tehran” by The Times newspaper. Chirol’s seminal article “The Middle Eastern Question” expanded Mahan’s version of the “Middle East” to now include “Persia, Iraq, the east coast of Arabia, Afghanistan, and Tibet”. Surprised? Yes, you read correctly -Tibet! The term Middle East was (and is) a colonial construct used to delineate British (and now West European and US) geopolitical and economic interests. These same interests help promote the usage of terminology such as “Islamic arts and architecture” (Image: Ria Press).

Mahan’s invented term “Middle East” was popularized by Sir Ignatius Valentine Chirol (1852-1929), a journalist designated as “a special correspondent from Tehran” by The Times newspaper. Chirol’s seminal article “The Middle Eastern Question” expanded Mahan’s version of the “Middle East” to now include “Persia, Iraq, the east coast of Arabia, Afghanistan, and Tibet”. Surprised? Yes, you read correctly -Tibet! The term Middle East was (and is) a colonial construct used to delineate British (and now West European and US) geopolitical and economic interests. These same interests help promote the usage of terminology such as “Islamic arts and architecture” (Image: Ria Press).

And of course a newly recognized region needs a new political status, thus it should come as no surprise that after WWI, Winston Churchill was chosen to be the head of a newly established “Middle East Department.” This department redefined Mahan’s original idea of the Middle East to include even more territories: Palestine and the Suez Canal as well as the newly created states of Iraq, and Trans-Jordan. Interestingly, Tibet and Afghanistan were eliminated from London’s Middle East Department. Boundaries were re-drawn based on oil and gas interests in the Persian Gulf region. Mal-appropriation indeed, to coin!

As the 20th century concluded and the 21st century began, Western media outlets, political platforms and entertainment venues all used the “Middle East” when referring to the geopolitically useful countries in what is geographically West Asia. The invention of the new term has led many people, including scholars and the media to refer to Iran as an “Arab” people or country. Hence it is a malapropism.

Mahan and Chirol’s invention (Middle East) provided the geopolitical terminology required to rationally organize the expansion of British political, military and economic interests into the Persian Gulf region. After the First World War, Winston Churchill (1874-1965) became the head of the newly established “Middle East Department”. Churchill’s department redefined Mahan’s original “The Middle East” invention to now include the Suez Canal, the Sinai, the Arabian Peninsula, as well as the newly created states of Iraq, Palestine, and Trans-Jordan. Tibet and Afghanistan were now excluded from London’s Middle East grouping. The decision to include non-Arab Iran as a member of the “Middle East” in 1942 was to rationalize the role of British political and Petroleum interests in the country (Image: Public Domain).

Mahan and Chirol’s invention (Middle East) provided the geopolitical terminology required to rationally organize the expansion of British political, military and economic interests into the Persian Gulf region. After the First World War, Winston Churchill (1874-1965) became the head of the newly established “Middle East Department”. Churchill’s department redefined Mahan’s original “The Middle East” invention to now include the Suez Canal, the Sinai, the Arabian Peninsula, as well as the newly created states of Iraq, Palestine, and Trans-Jordan. Tibet and Afghanistan were now excluded from London’s Middle East grouping. The decision to include non-Arab Iran as a member of the “Middle East” in 1942 was to rationalize the role of British political and Petroleum interests in the country (Image: Public Domain).

Much of the confusion may be attributed to the religion of Islam. The notion that many countries are Islamic (even different denominations) may have led people to group the “Middle East” countries. Then why omit Indonesia, Pakistan or even Bosnia and Chechnia for example, from the “Middle East”? The tendency to see Islam as a single homogeneous religion and culture is also responsible for the tendency to see all followers as Arabs and speakers of the same language, practitioners of the same culture. This misconception is wrong and misleading and does a particular disservice to Iran. The neologism “Middle East” confuses people who are not from the region and has the potential to make mockery of international norms. For example, Jack Shaheen, discovered that in the 1980s, almost 80% of North Americans believed Iranians to be Arabs or Arabic speaking people. However, the majority of Iranians speak Persian, a language in its own right and not a dialect of Arabic.

In the landmark textbook “Orientalism” (1979) by the late Edward Said (1935-2003) makes a similar point through his concept of “Orientalism.” In Said’s words

“Orientalism is a style of thought based upon ontological and epistemological distinction made between “the Orient” and (most of the time): “the Occident.” Thus a very large mass of writers, among who are poet, novelists, philosophers, political theorists, economists, and imperial administrators, have accepted the basic distinction between East and West as the starting point for elaborate accounts concerning the Orient, its people, customs, “mind,” destiny, and so on. . . . The phenomenon of Orientalism as I study it here deals principally, not with a correspondence between Orientalism and Orient, but with the internal consistency of Orientalism and its ideas about the Orient”despite or beyond any correspondence, or lack thereof, with a “real” Orient. (1-3,5) “

The cover of the Edward Said’s book “Orientalism” published in 1978 (Public Domain). The image is a section of Jean-Léon Gérôme’s (1824–1904) 19th-century Orientalist painting known as “The Snake Charmer”.

The use of “Middle East,” I would argue, is also case of ‘Orientalism,’ and a dangerous one. As noted in the Amazon.com summary of the impact of Said’s book:

“This entrenched view continues to dominate western ideas and, because it does not allow West Asia to represent itself, prevents true understanding.”

To paraphrase, the “Middle East” does not allow the countries in that region to express themselves as they are. It instead projects a regional stereotype.

The main point of this article is that there is a danger in replacing historical facts and names with gerrymandered politically based terminologies. Because of Western control over media and Internet, a neologism can enter the scholarship domains. However, when it becomes a malapropism, people are misled and authors lose credibility and factual accuracy to regional stereotypes that are not based in reality.

The wrong term can inappropriately group people who have very separate views of the world and their place in it. It is my view that the historical names like “West Asia” must not change, especially terms like “Persian Gulf” which have been used for thousands of years. We should not be consumed by our quest for war and thirst for oil, like Governor Gerry was consumed by his zeal for the Democratic Party. (See: The Priceless Heritage in a Name).

Neologisms can have their purpose, they show our creativity, our progress. But some neologisms, like “Middle East” should be discontinued when they cause confusion, mistrust, and dishonesty among people.

Footnotes:

2. Impact of Iranian Culture on East Asia

3. Kaveh Farrokh Interviews: Historia Rei Militaris, Persian Heritage Magazine and Voice of America.