As reported by the United Nations News CService (June 27, 2011) and the Persian-Language Jam e Jaam website (June 27, 2011), Iran’s Persian Gardens have become known as UNESCO World Heritage sites. As reported by the United Nations News CService (June 27, 2011):

The Persian Garden includes nine gardens in as many provinces of Iran. They exemplify the diversity of Persian garden designs that adapted to different climate conditions while retaining principles that have their roots in the times of Cyrus the Great in the 6th century BC.

The Tomb of Cyrus at Pasargadae which has been listed as a World Heritage site by UNESCO.

The Pasargardae tomb – a reconstruction by Professor Stronach.

Reconstruction of Pasargadae by the Persepolis-3D website: from left to right –north side, south side, east side and north side of Pasargadae. For more details on the above pictures and the architecture of Pasargadae, see Professors Stronach and Gopnik: Pasargadae.

The initiative was first reported by Iranian news services who noted that since December 2005 UNESCO had been cooperating with experts in Iran to tabulate a list of heritage sites pertaining to Persian Gardens in Iran. Dr. Adel Farhangi (the advisor of the director of the Research Center of the Cultural Heritage and Tourism Organization – ICHTO) had reported that a team of experts compied documents on sites (for submission to UNESCO) in the Fin Garden of Kashan, Shazdeh in Mahan, Fat’habad in Kerman, and Dolatabad in Yazd.

On the second part of the above video, Professor Stronach speaks about the Persian Gardens as part of his decades long research into the domain of Iranian Studies, which earned him the WAALM – Persian Golden Lioness Award of 2010.

The initiative to register the Persian Gardens was first made in a conference in Iran in 2004 which witnessed talks and presentations on the subject. It was also agreed that the submission of a registry for UNESCO would entail the study and classification of the architectural and civil engineering styles utilized in the construction of each of the gardens, as these would vary according to era (i.e. Achaemenid, Partho-Sassanian, Safavid, etc.).

The Persian Gardens have indeed withstood the test of time.

Origin of Persian Gardens at Pasargadae

Pasargadae was the imperial capital of Cyrus the Great and it was here where the “Persian Gardens” were formed. These were in essence an Achaemenid project which further developed, refined and expanded the Babylonian-Assyrian concept of the garden. The end-result of this was Pari-Daeza (Old Iranian: Park, Walled Garden) or the “Persian Garden”. The term Pari-Daeza is of Iranian origin and originally refers to the enclosed hunting grounds of the Median kings.

The Persian Gardens at Pasargadae were built in accordance with mathematically based geometric designs. There were 900 meters of channels constructed of carved limestone; these transported water throughout the garden. This was essentially a sophisticated irrigation system featuring stone water-channels and open ditches that were designed to channel water into small basins at every 15 meters in the garden.

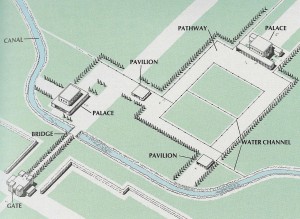

An overall top view of Pasargadae at Cyrus’ time. Note the canal, water channels; the two rectangles are gardens.

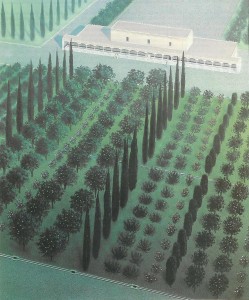

The garden itself was planted with a variety of fruit and Cyprus trees, flowers such as roses, lilies, Jasmines and exotic grasses. Arrian has described the gardens as

“a grove of all kinds of trees…with steams…” and encompassed by a large area of “…green grass” (Arrian, Expedition of Alexander, VI, 29).

A top view of a reconstruction of the Persian Garden at Pasargadae. Note water channels at rim of garden (see also History Channel program “Engineering an Empire: The Persians“).

The Pasargadae complex was indeed a unique symbiosis of Iranian (Medo-Persian), Anatolian (i.e. Ionian) and Mesopotamian civil engineering techniques. These would be the harbinger of Persopolis city-palace and other Achaemenid sites such as the recently discovered palace at Tang e Bolaghi.

Persian Gardens of the Post-Islamic Era

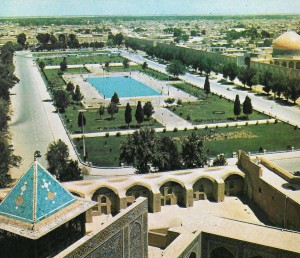

The Persian Garden has certainly survived into the post-Islamic era. The basis of such a design was built into the pavilion of Shah Abbas the Great (r. 1588 – 1629 AD) of the Safavid dynasty (1502-1736 AD).

The Maydan e Shah in Isfahan dated to the Safavid era.

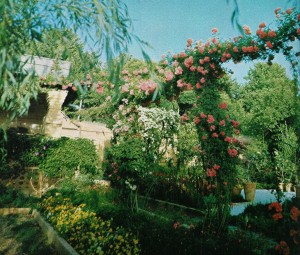

Many small towns and villages in modern Iran today continue to have gardens that derive their inspiration from the Achaemenids of old.

A Persian garden in Tehran in 1971.

For more photos of post-Islamic Persian Gardens kindly click on the photo below:

Legacy of the Persian Gardens on Civilization

Cyrus’ gardens have exerted a profound legacy outside the borders of Iran, and especially in Europe. The Greeks adopted the Persian garden after Alexander’s conquests of Persia and most likely during the ensuing Seleucid era. The Persian term Pardis entered the Roman lexicon which facilitated its transmission to other European languages. The Greeks, Romans and succeeding European civilizations were to build parks and gardens on the Persian model. The breathtaking gardens of Versailles France, the baroque gardens of Belvedere Palace of Austria or the Butchard Gardens of Victoria Canada may never have existed today had it not been for Cyrus’ gardens at Pasargardae. Even the Bible commemorates the word “Paradise” in its lexicon.

The gardens at Versailles Place in France.

The influence of the Persian Gardens has also spread to the Orient, notably China and then Japan, probably mainly due to the arrival of Sassanian refugees to China after the collapse of the Sassanian Empire in the 650s AD, although earlier influences cannot be ruled out.

A Chinese Garden.

The most notable example of the influence of Persian Gardens in the Indian subcontinenet can be found in India’s Taj Mahal place built by the Moghuls (1526-1707).

The Taj Mahal, completed by 1648, is also a UNESCO World Heritage site. The master architect of Taj Mahal was an Iranian named ‘Ostad Isaa Afandi’ from Shiraz. The builders were also Persian stone masons, imported from Iran by Mogul Shah Jahan, as per the request of the aforementioned Chief Master Architect Afandi. The white marble for the Taj Mahal was imported from Isfahan. The calligraphy was created by the Persian calligrapher Abd ul-Haq, who came to India from Shiraz, Iran, in 1609. Shah Jahan conferred the title of “Amanat Khan” upon him as a reward for his “dazzling virtuosity”. Another striking Iranian influence can be seen in the design of the gardens and waterworks of the locale. Much of the fauna of Taj Mahal’s Persian gardens were directly imported from Iran. The term “Taj Mahal” is Persian for “The Royal Gounds” or more literally “The Crown Locale”.

Video recreation of the arts and architecture of the Safavid era (1501-1722). Note the emphasis on the Safavid Persian Gardens featured in the video.