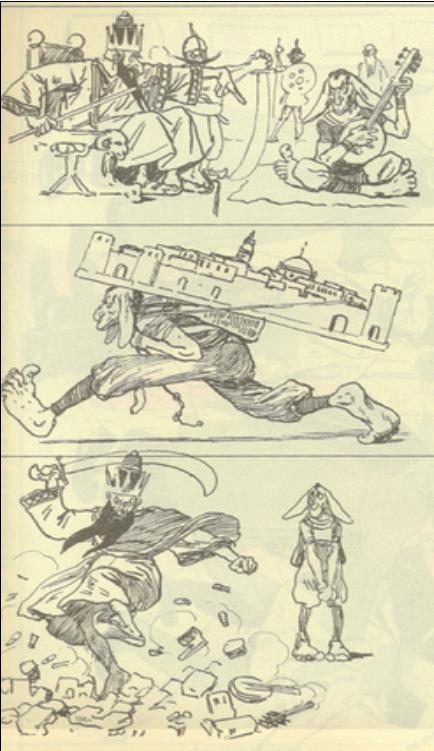

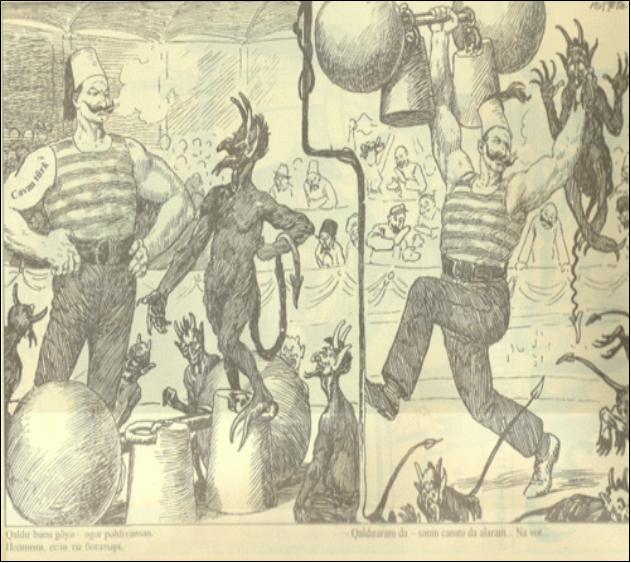

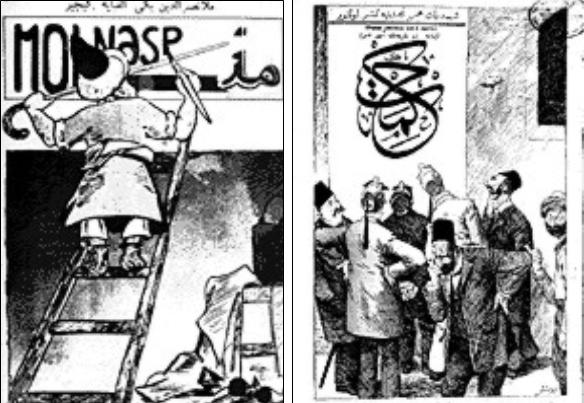

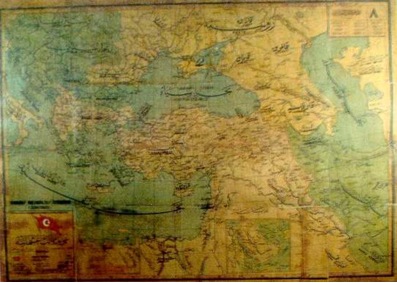

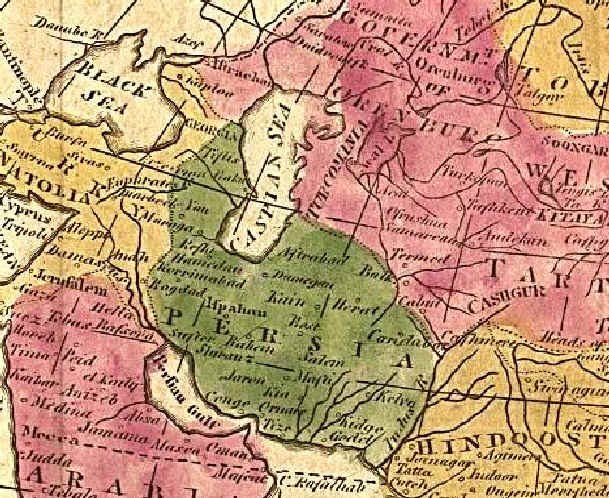

Yusef Amiri: Our previous discussion ended on the topic of Iran’s forced cession of the Caucasus, Arran and Shirvan following the humiliating treaties of Golestan and Turkmenchai. During the time of the Russian Tsars a number of programs were put intio place to deny the ties of Iran’s historical and cultural presence in the region and to sever all roots between Iran and the Caucasus. Expand on these Russian programs – گفتوگوی پیشین با این موضوع به پایان رسید که پس از جداسازی قفقاز و اران و شروان از ایران در قراردادهای ننگین گلستان و ترکمانچای در زمان تزارهای روسیه، برنامهی سازمانیافتهای ریخته شد که حضور تاریخی ایران و فرهنگ ایرانی در این منطقه انکار شود و رشتههای ارتباط میان ایران و قفقاز بریده شود. دربارهی این برنامهی روسیه بیشتر بگویید. NOTE: There is an academic version of this article available at Academia.edu: – نقش امپراتوری روسیه در قطع ارتباط های ایران و قفقاز- Kaveh Farrokh: Our previous interview focused on the Soviet Tzarist policies of systematically attacking the Persian language and cultural heritage in the Caucasus, especially from the 1850s. The role of the Ikenci newspaper was also discussed, especially in how it openly attacked the Persian language and culture as backward and “oppressive”. We also discussed how the Ikenci’s editor Hassan Bey Zardabi consistently denigrated the Persian language as “the braying of a donkey”. Hassan Bey Zardabi, the editor of the Czarist Russian supported “Ikenci” (Cultivator) newspaper. The “Ikenci” was very racist and anti-Persian, drawing protests from many members of the Caucasus’ Persian-speaking population. Russia continued to support the Ikenci and ignored the newspapers’ blatant racism and Human Rights violations. Zardabi hated the Persian language to such an extent that he even invented new words to replace Persian words commonly used in Azarbaijani-Turkic. By the early 1860s, local sentiments against Russification had been successfully channeled away from an Iranian cultural-literary expression into a distinctly Turkic-Tatar form. As mentioned in our last interview only one of Baku’s 41 primary schools was teaching Persian in 1910. It was the Tsars who took the lead in shaping the anti-Iranian character of pan-Turkism. The writings of Ismail Gaspirli in the Russian-sponsored Terjumen greatly helped the Russians to steer the intelligentsia of Baku away from the Iranian cultural realm towards pan-Turkism. The next wave of Russian-sponsored literature was the Mulla Nassredin publications in promoting anti-Persian and anti-Islamic sentiments in the Arran-Albania region. Cartoon of the Czarist-supervised Mulla Nassreddin Magazine which often published anti-oriental cartoons in the Caucasus, especially against Iran and Persian speakers. The above cartoon portrays Persian-speakers as donkeys with the Shahs of Iran as cruel, destructive despots. This was part of the Russian Czarist propaganda campaign to show Iran as a backward and ignorant “oriental” country. The notion of equating the Persian language with the “braying of a donkey…” was first made by Hassan Majidi Zardabi (or Hasan Bey Zardabi) , the chief editor of the Ikenci newspaper (1875-1877) published in Baku (consult Hajibely, Jeyhoun Bey, 1930, “The Origin of the National Press in Azerbaijan” in The Asiatic Review, 26(88, p 757). Much of this anti-Persian propaganda was to continue into the Soviet era and beyond. Picture source: Azer.com. Mulla Nasrredin is the name of a satirical-comical character highly popular in Turkey, Iran, the ROA as well as the Georgian republic. The journal Mulla Nasrredin was founded in 1906, and resumed the anti-Iranian and anti-Shiite tradition of Akhund-Zadeh’s Akinci plays (see Zenkowsky, 1960, p.95) as well as Zarbadi’s former newspaper, Akinci. Content Analysis of a number of cartoons published by the Mulla Nasrredin papers provides evidence of consistent anti-Iranian and anti-Islamic imagery. A number of these cartoons are now posted on the official website of the ROA: www.Azer.com. Examples include the depiction of Persian-speakers as donkeys with their rulers as oriental despots, Turks as white-skinned Herculean heroes overpowering and dominating “orientals” (presumably Persians) portrayed as satanic dark-skinned gnomes, the ascendancy of Latin-based script over the Arabo-Persian script (especially the “complicated” nature of the latter) and Shiite Mullahs as representative of the “orient” and backwardness. The Akinci newspaper was finally shut down in 1877 by Czarist authorities for its increasingly anti-Russian publications. Nevertheless the Akinci paper had served Czarist objectives with success. Molla Nassredin cartoons depicting Turks as superhuman heroes and “orientals” (Persians) as satanic dark-skinned gnomes. Note Turk on left with the term “Cavan Turk” (Young Turk) tattooed on his right arm. Russias’ greatest success in socio-cultural engineering was in how it erased the Iranian identity of the Caucasian Khanates by virtually re-inventing all of the region’s inhabitants as “Turks”. The main tool in this process was the eliminaton of the Persian language and the promotion of local Turkic dialects in its place . (Source: http://www.azer.com/aiweb/categories/magazine/43_folder/43_articles/43_mollamag.html) Thorez (see Encyclopedia Iranica) has observed that “Although throughout history the Caucasus has usually been incorporated in political entities belonging to the Iranian world…Russia took it…from the Qajars (1779-1924), severing those historical ties.” The Persian language was a key factor that provided a cultural bond between Iran proper and the Transcaucasus. Swietochowski has noted that “The hold of Persian as the chief literary language in Azerbaijan was broken, followed by the rejection of classical Azerbaijani, an artificial, heavily Iranized idiom that had long been in use along with Persian…This process of cultural change was initially supported by the Tsarist authorities, who were anxious to neutralize the still-widespread Azerbaijani identification with Persia.” (Swietochowski, 1995, p.29). This policy was consistent with Czarist policies with respect to other recently conquered non-Russian nationalities of the empire Swietochowski further notes that (1995, p. 29): “In doing so, the Russians resorted to a policy familiar in other parts of the empire, where Lithuanians, for example, were sporadically encouraged to emancipate themselves from Polish cultural influences, as were the Latvians from German and the Finns from Swedish.” During the Czarist era, the prevalence of the Persian language was weakened due to three processes: (a) Russian promotion of anti-Iranian literature and the rejection of Persian as a common and literary language. (b) rise of pan-Turkism, which was partly facilitated by Czarist policies. (c) rise of a new Turkish language that was being developed under Ottoman and Russian-Tatar influences. Nevertheless, the policy did not meet with total success, notably among the Iranian-speaking Talysh who have not forfeited their heritage to the present. An undated photo of a Talysh woman and her child. Despite massive Russian and later Soviet political pressure, ethno-engineering efforts and funding, the Talysh have retained their Iranic identity in Arran (modern Republic of Azarbaijan). By the early twentieth century, there had been a virtual explosion of Moscow-supported pan-Turkist writers in the Caucasus’ Arran-Albania region including Ali Mardan bey Topchibashev, Hashem bey Vaziri, Ahmad bey Aghaoglu (Aghaev), Mohammad Hassan Hajinzadeh (also known as Hajinski), Ali Husseinzadeh and Mohammad Agha Shahtahvili. A brief analysis of the pan-Turkism of these writers clearly shows the impact of European cultural engineering. Molla Nassredin cartoons depicting the ascendancy of “European” Latin-based script over the “Oriental” Arabo-Persian script (above left). Local Caucasians contemplating on the ” complicated nature” of Arabo-Persian script (above right). (Source: http://www.azer.com/aiweb/categories/magazine/43_folder/43_articles/43_mollamag.html) Mohammad Agha Shahtahvili said very clearly that the people of the present-day Republic of Azarbaiajn (former Arran-Albania) “…should love the Turkic world above anything else” (as cited from Zenkowsky, 1960, p.98). There is no mention whatsoever of the region’s long-standing cultural and historical association with Iran which can be traced for thousands of years. Readers may be shocked to learn how certain members of that republic’s citizen’s lack knowledge of this history and are even displeased with this information. How was Shahtahvili‘s Turkic world defined? Ahmad bey Aghaoglu clearly defined “The Turkish world” which according to him: “…begins with…Manchuria…Balkan reaches, Asia Minor…Caucasus…Volga…Samara…Siberia…Arctic Sea…Mongolia…Russian and Chinese Turkestans, Bukhara, Khiva, Persian Khorrasan…southern shores of the Caspian Sea…the two Azerbaijans…Russian and the Persian” (LaBonne, 1922, pp.297-399). Ahmad bey Aghaoglu (Aghaev) who was among the first Russian supported pan-Turkists to define the boundaries of the greater pan-Turk super-state. It is interesting that Russia supported such views, despite the fact that pan-Turkism also claims Russian territory. This was mainly because pan-Turkism, with its highly anti-Persian philosophy, was seen as a useful tool by Moscow to weaken Iran from within. The Communist successors of the Czars continued to sponsor pan-Turkism against Iran throughout the 20th century. This certainly fits the definition of Vamberry which we discussed earlier – but here is one great irony. Russia, an active proponent of pan-Turkism was playing a dangerous game. This is because pan-Turkism is a double-edged sword for Russia – yes, it can threaten Iran to the core but it can also threaten Russia. Russia however calculated that by channeling pan-Turkism against Iran it could somehow “manage” this or “channel” this largely against Iran. The Russians in fact made great efforts to “Russify” or “Europeanize” the elites of the former Iranian khanates. This appears to have been largely successful as few in the Arran-Albania region see themselves as connected to Iran, the Middle East or the Islamic world – but they do see a powerful connection between them and Europe and especially to Turkey which they appear to regard as a European or Europeanized state. That too is ironic as modern Turks (at least at the popular level) have long moved away from the heady days of pan-Turkism and are in fact becoming aware or re-discovering their strong and shared cultural associations with their close cultural cousins: the Iranians. Turks and Iranians enjoy deep cultural relations – the vast majority of modern Turks simply do not regard their fringe pan-Turkist movement seriously. Let us observe one more Arrani-Albanian writer who promoted pan-Turkism: Mohammad Hassan Hajinzadeh. He noted very clearly that “…wherever the Turks have set foot should belong to the Turks” (LaBonne, 1922, p.399). Once again note the shocking impact of European cultural engineering – a process which has borne very dangerous consequences for Iran both past and present. This was to continue well into the Communist era – after the fall of the Czars during World War One in 1917. Hopefully later in this interview we will get the opportunity to explore the European roots of pan-Turkism. Mohammad Hassan Hajinzadeh (Hajinsky) who clearly defined the entitlements of pan-Turkism. Few realize that one of the main centers for the European cultivation of pan-Turkism was in the Caucasus. It was many of these same thinkers who went to the Ottoman Empire in the early 20th century to “convert” many Ottomans into pan-Turkism. Before their exposure to pan-Turkism, the Ottomans were a vibrant multi-ethnic empire in which Turks, Armenians, Greeks, Arabs and other nationalities lived in harmony. Pan-Turkism was one of many factors that helped destroy the Ottoman Empire from within. When the activists of the Musavat party adopted the name “Azarbaijan” for the Arran-Albania region in May 1918, pan-Turkist sentiments virtually skyrocketed. Ali Mardan bey Topchibashi (Topchibashev) told the Ottoman Sultan in Istanbul: “With divine grace, I have managed to attain my goal: to see the Caliph of all Moslems and the Padishah of all Turks. Your majesty! Some time ago you received the delegation of the small Turkic state [the Republic of] Azarbaijan, and you deigned to say, ‘The Azarbaijanis are my favorite children”. We Azarbaijanis remember this honor…and shall live by the grace of the Caliph of all Moslems, the Padishah of Ottoman Turks, our Great brother” (as cited by Ratgauzer, 1938, p.37). Map of the Ottoman Empire, western and northwestern Iran and the Caucasus drafted in 1912 by the Ottoman Turks. Note that the term “Azarbaijan” is only applied to Iran’s northwest province. The name Azarbaijan is not used in refernece to territories to the north of the Araxes River. It would be up to the pan-Turkist Musavat Party to invent or ”borrow” the name of Azarbaijan for their newly created Transcaucasian republic on May 27, 1918. There are two errors in Topchibashi’s statement here: Arran-Albania was never called “Azarbaijan” until 1918 – the name being historically confined to the province of Azarbaijan in the northwest of Iran. Second, the “Azarbaijanis” and the Arranis had bitterly fought against the Ottoman Turks under the banner of Iran for centuries. How was it that these documented and well-established historical facts had been simply “erased”? How had this mass brainwashing taken place in the Caucasus? Ali Mardan bey Topchibashi (Topchibashev) defined the Caucasus as a satellite of the Ottoman Empire. Topchibashi made no reference whatsoever to the thousands-year long cultural and historical association of his native south-eastern Caucasus and Iran. This historical amnesia was overwhelmingly the result of Russian manipulation of “education” -especially history, and culture (recall the anti-Iranian Mulla Nassredin cartoons we discussed in previous interviews). Recall once more how Russian Persophobic policies had reduced the total number of Persian-speaking schools in Baku to just one by the early 1900s. Persian-speakers were put down in the Russian sponsored press in the Caucasus as were the Shiite clergy due to their ties with Iran. While these revelations may appear shocking to many readers, we must note that Czarist Russia had been engaged in intense cultural engineering for decades – they aimed and succeeded at erasing the Caucasus’ Persian legacy from the much of the local populace. Russia was pleased that their sponsorship of pan-Turkism had the immediate “side effect” of promoting intense anti-Persianism among their Caucasian subjects. Ali Husseinzadeh for example, who composed the poem of “Turan” or a great pan-Turk state, tirelessly demanded that the Caucasus be “liberated” from Persian linguistic and cultural influences. But Russian ethno-engineering was not just confined to the Caucasus. Russia also invested in promoting anti-Persian attitudes at the educational and cultural level among Kurds in the Ottoman Empire and Iran. Their aim was to again weaken the cultural and historical ties of an Iranian people from the greater Iranian realm. Cover of 22nd edition of Molla Nassredin magazine with comical portrayal of Shiite Mullah. Russia expended considerable efforts towards associating Iran with backwardness and ignorance while carefully promoting pan-Turkism against the Perisan language and Iran. These policies continued under the Communist regime and are now being cultivated by political lobbies in various countries. (Source: http://www.azer.com/aiweb/categories/magazine/43_folder/43_articles/43_mollamag.html) The Russians sponsored and supported Abdulrazzag Bedir Khan of the Bedirkhanid clan who had left his kinsmen in Istanbul for exile in Russia in 1906 due his falling out with Sultan Abdul Hamid. Abdulrazzaq left Russia in 1912 to arrive in the west of Iranian Azarbaijan. As soon as he arrived be worked to vigorously promote separatist and Persophobic sentiments among the local Kurds against Iran. This task was easy to accomplish: Russian troops were occupying much of northern Iran and Iranian Azarbaijan, therefore Abdulrazzaq was guaranteed that his efforts would not be molested by any Iranian authorities. Qajar central authority was already weak to begin with – thanks to decades of Russian meddling. Russian troops, with their Shashka Sabers drawn, pose for the cameras after having executed Iranian democracy activists in Tabriz (circa 1909-1910). Just as Russian troops were crushing Western Asia’s first democracy movement in Iran, the Czarist regime was engaged in cultural engineering to promote Persophobia among Iranian Kurds. Although Abdulrazzaq was from the Ottoman Empire, Russia had no interest in inculcating such sentiments among Ottoman Kurds. This was despite the fact that Russia and the Ottoman Empire had fought several bloody wars over the centuries. The Ottomans and the Russians had found common ground against Iran’s ancient cultural legacy in the region. Russia was simply continuing her long-standing tradition of weakening Iran by wars and diminishing the Persian cultural and linguistic legacy through educational and political processes. From Moscow’s viewpoint, promoting Kurdish separatism inside Iran (again) using linguistic differences could help lay the basis of Iran’s cultural implosion from within. Agir Sharo and Mussa Pan-Kurdish Separatist leaders of the PJAK movement which advocates violence and ethnic conflict to achieve its aims. Few are aware that Kurdish separatism in its anti-Iranian sense originates in the efforts of the Ottoman and Russian Empires followed by the Soviet Union. The PJAK movement is no different from its predecessors in that it has ties to foreign governments who like the past Russian and Ottoman empires, ultimately seek the balkanization of the Iranian state (Photo source: DailyMe). The destruction of the Iranian state would allow the Russians (or other powers) to expand their political and economic interests into Iran against minimal opposition. To that end, Abdulrazzaq published a journal named Kurdistan in Kurmanji Kurdish and Turkish in Urumiyeh. The Russians also funded a cultural association in Khoy and followed this with a school, ensuring that the pupils would use the Cyrillic alphabet and learn the Russian language and literature. The syllabus of these schools de-emphasized the Kurds’ Iranic associations with Iran. This process was virtually identical to the anti-Iranian cultural policies that the Russians had had in place in the Caucasus since the mid 19th century. The Russians would again do this when they invaded Iran in 1941 – they set up the exact same type of “cultural” associations in Azarbaijan and the western (predominantly Kurdish) regions of that province. A common claim made at present by pan-Kurdist writers is that the ancient Medes have been “oppressed” by the “Persians’ since antiquity – notably by Cyrus the Great and the Achaemenids. These Persophobic beliefs can be traced to the efforts of Romanov regime in the late 19th century and early 20th century when they worked hard to organize Persophobia among Kurds. See also ezcerpt below in Persian: دروغ دیگری که همهکردانگاران (pan-Kurdist) میپراکنند و شایع میکنند آن است که کوروش و هخامنشیان مادها را قتل عام کردند. به ادعای آنان مادها نیاکان بیفاصلهی کردها هستند. یعنی «قوم فارس» – منظورشان فارسیزبانان امروز ایران است – از قدیم به کردها ستم میکرده است! The efforts at de-Persianization especially among the Kurds were simultaneously joined by efforts at arming Iranian tribes to the detriment of the political integrity of the Iranian state. By 1901 Russia was sending weapons to a number of tribes (especially the Kurds) in efforts to further expand its influence. Particular emphasis was placed on recruiting tribal levies to the Persian Cossack brigade to extend Russian influence into Iran’s provinces, notably in the Azarbaijani, Kurdish and Bakhtiari areas. Russia’s approach was unique in that it sought to further its geopolitical objectives by combining “educational” methods with the age-old practice of forging political-military links along Iran’s peripheral provinces. Perhaps more interesting are Russian “conferences” that were set up in (Russian) occupied Iranian Kurdistan in 1917. These “conferences” aimed to unify Kurds from Iran and the Ottoman Empire towards a pro-Russian policy. The Russian Charges d’affairs in Tehran at the time (Minorsky) went so far as to advocate “national rights” for the Kurds within Iranian territory. The term “national rights” sounds very similar to the “human rights” now cited by pan-Turks and other separatists to promote ethnic discord. Note how the misuse of terminology deliberately confuses the legitimate Human Rights of all peoples with self-serving geopolitical objectives. Map of Iran in 1805 before the territorial losses to Russia of the Caucasus and Central Asia. Iran also lost important eastern territories such as Herat which broke away with British support (Picture source: CAIS). These methods would resurface in twentieth century to menace the territorial integrity of the Iranian state – especially during the rise of the Communists of Moscow and Baku. Very similar “conferences” have surfaced in Baku since 1991 as well as numbers of western political and academic venues. Even more surprising are papers of this type that have recently been promoted in Iranian studies venues. It is also noteworthy that as all of this ethno-engineering was taking place in the Caucasus and among the Kurds, the Qajar administration in Iran made no diplomatic protests and took no cultural actions to combat Russian Persophobia in the Caucasus or in Kurdistan. It would appear that the Qajar administration was either disinterested or oblivious as to what was happening at that time.

Question 1: Imperial Russia and its Programs to Sever ties of Iran and the Caucasus2020-07-01T22:37:54-07:00

[of severing Iran-Caucasus ties].