The posting below is from a segment of the article by Mark Adderley entitled “Theories about the Origins of the Arthurian Legend” – this was originally posted in the Mark Adderley website (the link is no longer operational). Kindly note that the pictures and accompanying descriptions do not appear in the original article by Adderley.

=================================================

As proposed by Nickel, Littleton, and Malcor, the inspiration for Arthur was Lucius Artorius Castus, the prefect of the 6th Legion, stationed in York. Artorius led the 6th Legion overseas to Armorica (Brittany) on a successful punitive raid, and many of the soldiers he led were Sarmatians.

There are a number of striking resemblances between the Sarmatians and their beliefs and legends, and elements in the Arthurian legend. The Sarmatians:

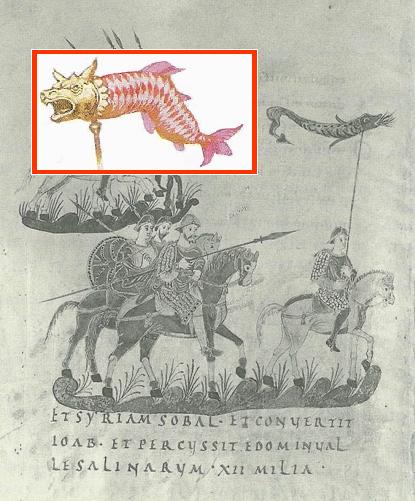

Russian reconstruction of King Arthur and his Sarmatian cavalry (Source: Our Russia); note Iranian dragon standards of the cavalrymen also seen in the armies of the Parthians and Sassanians.

[2] used a dragon standard in battle, as Arthur is in some medieval illustrations.

A depiction of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae and Sir Thomas Mallory’s Le Morte d”Arthur. Note the windsock carried by the horseman (Farrokh, page 171, Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War-Персы: Армия великих царей-سایههای صحرا) – this item was bought from the wider Iranian realm (Partho-Sassanian Persia, Sarmatians, etc.) into Europe by the Iranian-speaking Alans. The inset depicts a reconstruction of a 3rd century CE Partho-Sassanian banner by Peter Wilcox (1986).

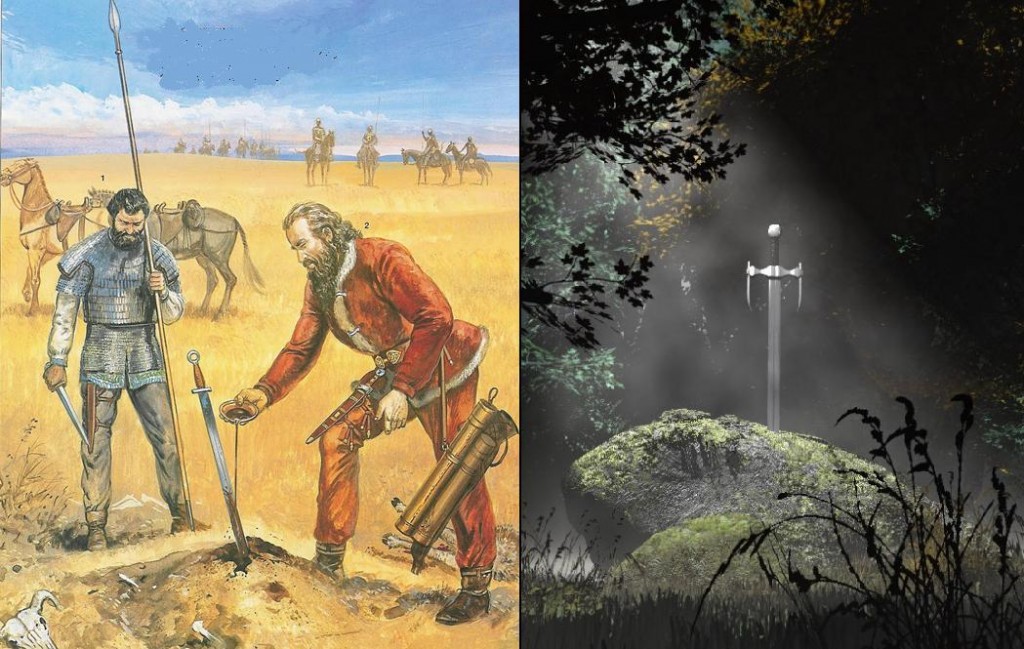

[3] venerated a naked sword set in the ground or a platform, resembling the story of the sword in the stone.

A reconstruction by Brzezinski and Mielczarek (2002 ) of Iranian-speaking Sarmatian warriors paying their respects to a fallen comrade in Europe (circa 1st century CE) – note the ritual of thrusting the fallen comrade’s sword into the earth. At right is a screenshot of the Excalibur sword of King Arthur thrust into the stone (Movie “Excalibur“, 1981, John Boorman). This is one of many parallels between the Arthurian legends and the mythologies of the ancient Iranians (Pictures used in Kaveh Farrokh’s lectures at the University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division).

[4] used a cauldron full of hashish in their religious ceremonies, a bit like the Grail. [5] told the story of Batradz, a hero whose life was bound up in his sword. Dying, he asked his last companion to cast it into the sea. The companion’s failure to report the sign demanded by Batradz indicates that he has not done so. When he finally throws the sword in, the sea turns blood red. This story certainly resembles the story of Arthur, Excalibur, and Bedivere.

Roman tombstone from Chester (housed at Grosvenor Museum, item #: 8394907246), UK depicting Sarmatian horseman attired like other kindred Iranian peoples such as the Parthians and Sassanians (Source: Carole Raddato, uploaded by Marcus Cyron in Public Domain).

The tombstone fragments of a Sarmatian/Alanian standard bearer were found at Chester (Deva) in 1890. This is unique evidence of the presence of heavily armoured Sarmatian cavalry from the earliest third century A.D. The two fragments of the tombstone (now in the Grosvenor Museum in Chester) show a horseman wearing a cloak and turning to the right. He holds aloft, with both hands, a dragon standard of the Sarmatian/Alanian type, and his conical helmet, with a vertical metal frame, is of the same pattern. A sword hangs at his right. Both man and horse are shown clad in tightly fitting scale armour. This attire for man and mount was characteristic of Sarmatian/Alanian heavy cavalry.

Sarmatian armour discovered near Hadrian’s Wall in England (Source: Periklisdeligiannis); this most likely belonged to an Iranian-speaking Alan or related Ia-zyges cavalrymen serving as mercenaries in the Roman army in Britain.

References

Note: Many of the extracts from chronicles cited above can be found in Chambers’ Arthur of Britain.

Alcock, Leslie. Arthur’s Britain. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971.

Ashe, Geoffrey. “The Arthurian Fact.” The Quest for Arthur’s Britain. Ed. Geoffrey Ashe. London: Paladin, 1968. 27-57.

– – – . “A Certain Very Ancient Book: Traces of an Arthurian Source in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History.” Speculum 56 (1981): 301-23.

– – – . The Discovery of King Arthur. New York: Henry Holt, 1985.

– – – . “The Origins of the Arthurian Legend.” Arthuriana 5.3 (1995): 1-23.

Chambers, E. K. Arthur of Britain. London: Sidgewick and Jackson, 1927.

Charles-Edwards, Thomas. “The Arthur of History.” The Arthur of the Welsh: The Arthurian Legend in Medieval Welsh Literature. Ed. Rachel Bromwich, A. O. H. Jarman, and Brynley F. Roberts. Cardiff: U of Wales P, 1991. 15-32.

Dumville, David N. “Sub-Roman Britain: History and Legend.” History 62 (1977): 173-92.

Gildas. The Ruin of Britain and Other Works. Ed. and trans. Michael Winterbottom. Chichester: Phillimore, 1978.

Green, Thomas. Concepts of Arthur: Early Arthurian Tradition and the Origins of the Legend. Stroud: Tempus, 2007.

Jackson, Kenneth Hurlstone. “The Arthur of History.” Arthurian Literature in the Middle Ages: A Collaborative History. Ed. Roger Sherman Loomis. Oxford: Clarendon, 1959. 1-11.

– – – . “Gildas and the Names of the British Princes.” Cambridge Medieval Celtic Studies 3 (1982): 30-40.

Jordanes. The Gothic History. Trans. C. C. Mierow. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1915.

Littleton, C. Scott, and Ann C. Thomas. “The Sarmatian Connection: New Light on the Origin of the Arthurian and Holy Grail legends.” Journal of American Folklore 91 (1978): 513-27.

– – – , and Linda A. Malcor. From Scythia to Camelot: A Radical Reassessment of the Legends of King Arthur, the Knights of the Round Table, and the Holy Grail. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 2000.

Morris, John. The Age of Arthur: A History of the British Isles from 350 to 650. Vol. 1. Roman Britain and the Empire of Arthur. Chichester: Phillimore, 1973.

Nennius. British History and The Welsh Annals. Ed. and trans. John Morris. London: Phillimore, 1980.

Nickel, Helmut. “The Dawn of Chivalry.” From the Lands of the Scythians. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1975. 150-52.

Padel, O. J. Arthur in Medieval Welsh Literature. Cardiff: U of Wales P, 2000.

– – – . “Recent Work on the Origins of the Arthurian Legend: A Comment.” Arthuriana 5.3 (1995): 103-14.

Sidonius Apollinaris. The Letters. Trans. O. M. Dalton. Oxford: Clarendon, 1915.