The article “Persian roots of Puccini’s opera Turandot” (posted 29 November 2019) on Leiden University’s Leiden Medievalists Blog has been penned by Dr. Asghar Seyed Gohrab, Senior University Lecturer at Leiden University. who has dedicated this article to his friend Dr. Rokus de Groot (University of Amsterdam). The article was bought to the attention of Kavehfarrokh.com by Anosh Tozie through the Facebook venue.

Readers further interested in Europa-Iran ties can access more resources on this domain in the below links:

- Europa & Ancient Eire-An [Ancient Iran/Persia and Greater Iran]

- Farrokh, K. (2016). An Overview of the Artistic, Architectural, Engineering and Culinary exchanges between Ancient Iran and the Greco-Roman World. AGON: Rivista Internazionale di Studi Culturali, Linguistici e Letterari, No.7, pp.64-124.

- PhD Dissertation by Sheda Vasseqhi (University of New England; academic supervision team Academic advising Team: Marylin Newell, Laura Bertonazzi, Kaveh Farrokh): Positioning Of Iran And Iranians In Origins Of Western Civilization.– see also News Release …

- UBC Lecture (November 29, 2019): Civilizational Contacts between Ancient Iran and Europe

================================================================

What is the place on earth that saw the sun only once? What is it that all beings have, human beings, angels, fairies, demons, anything that grazes and flies, heaven and earth, anything that God has created? How did a Persian story grow to a world opera?

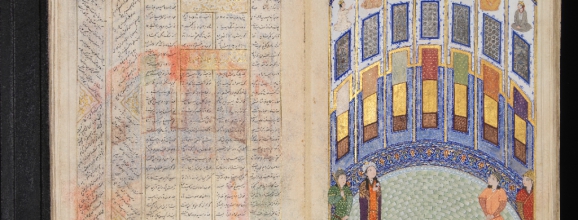

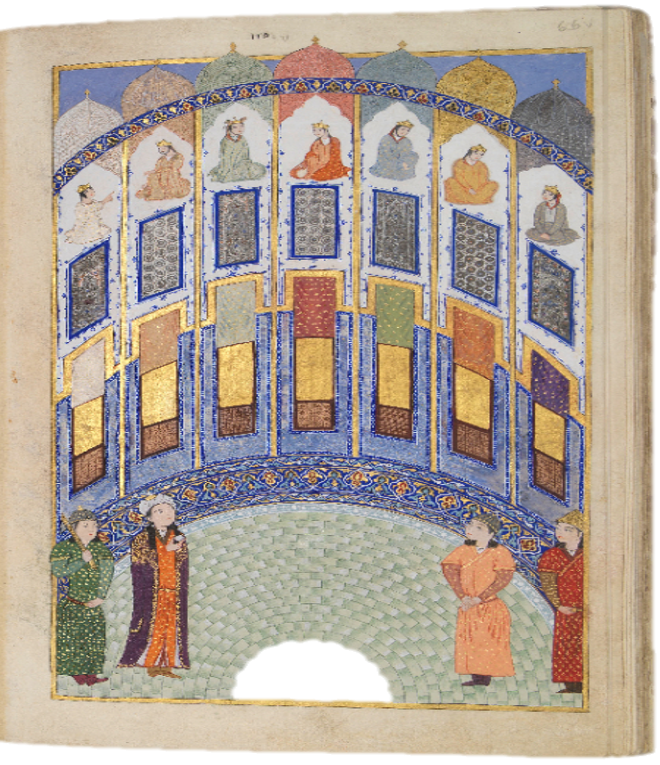

Bahram Gur in the Room of the Seven Portraits (Leiden Medievalists Blog & Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon).

Europeans inspired by Persian culture

Persian culture has captured the attention of European artists from antiquity. Persian imperial history, myths and legends, religions, and poetry have all in one way or another enticed European artists, musicians and scholars. European composers were inspired by Persian subjects creating artistic works. Johann Strauss’s Persische March (1864), Thomas Arne’s (1710-1778) opera Artaxerxes, George Friedrich Handel’s Serse (1738), Richard Strauss’s Also sprach Zarathustra, based on Friedrich Nietzsche’s Also sprach Zarathustra, are famous examples, which are inspired by Persian culture and history.

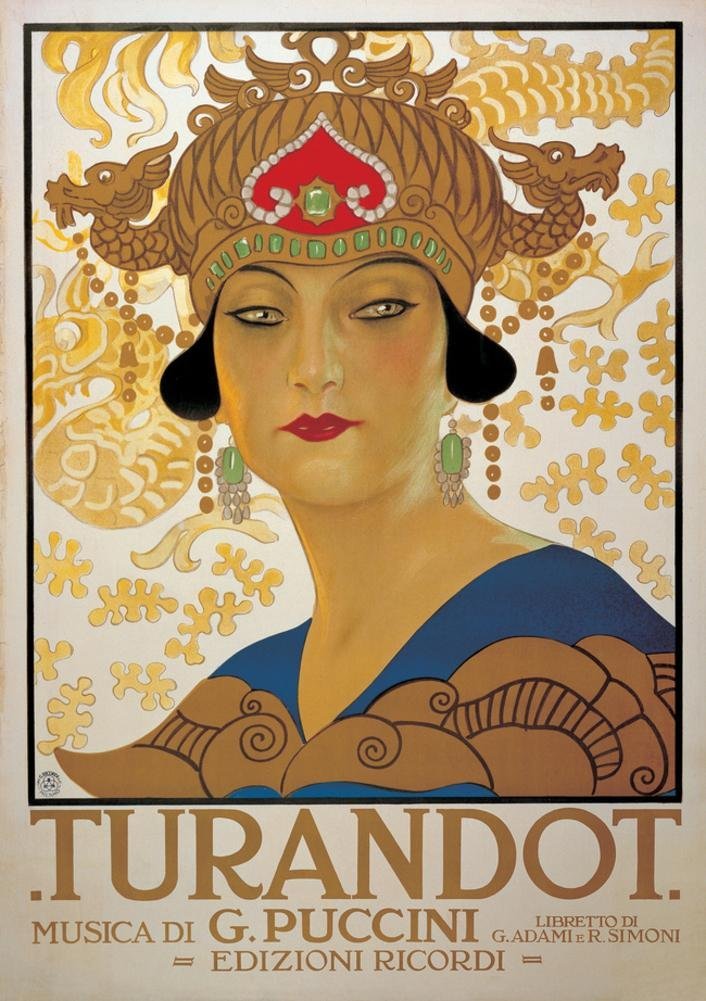

Promotional poster for Giacomo Puccini’s opera Turandot in 1926 (Leiden Medievalists Blog & Public Domain).

Turan’s daughter

But how did a medieval Persian anecdote inspire Puccini’s opera Turandot? The name derives from the Persian compound name Turan and dokht, meaning the daughter of Turan. Dokht is a shortened form of dokhtar or ‘daughter,’ ‘girl.’ As Persian belongs to the Indo-European family of languages, the word dokhtar has cognates in European languages. Turan refers to the north eastern borders Persia. Turandot recounts the story of a Chinese princess who kills her suitors when they fail to decipher riddles.

Puccini: Nessun Dorma from ‘Turandot’ – BBC Proms

Seven Beauties

As a recent investigation has shown (Mogtader & Schoeler, 2019), this story appears in anecdotal form in twelfth century Persia in at least two different sources.

Scene from the opera Turan Dokht by Miranda Lakerveld (Leiden Medievalists Blog & Copyright: Nichon Glerum).

The first source is the Persian masterpiece Seven Beauties, by the Persian poet Nezami (d. 1209) who recounts the romantic history of the pre-Islamic Persian king Bahram. The plot of this story is very complex, filled with mathematical, astronomical, cosmogonic, medical and mystical symbolism. A simplified plot runs as follows. In his early years, Bahram is sent away for education. During a hunting expedition, he comes across a temple. He goes inside the building and sees portraits of seven princesses from the Seven Regions of the world. He instantly falls in love with all of them. As soon as he comes back to Persia, he builds seven pavilions and invites the brides to his palace complex. From Saturday to Friday he visits each night one princess, telling him erotic and didactic stories. Each of these princesses teaches him a lesson and is instrumental in his development as a human being. He starts with the Indian princess in the black pavilion, and then on Sunday, the day of the Sun, goes to the Byzantine princess Humay, till he visits the Persian princess in the White pavilion on Friday, the day of Venus. The colour symbolism, from black to white (leading finally to radiance and colourlessness) is based on astronomical/astrological, mathematical and spiritual symbolism. This journey from black to white also refers to Bahram’s spiritual development from darkness and ignorance to light and illumination, uniting himself with the source of light. He grows to a Perfect Man and an ideal king.

Bahram Gur in the Room of the Seven Portraits (Leiden Medievalists Blog & Collection Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon).

The Ruthless Princess

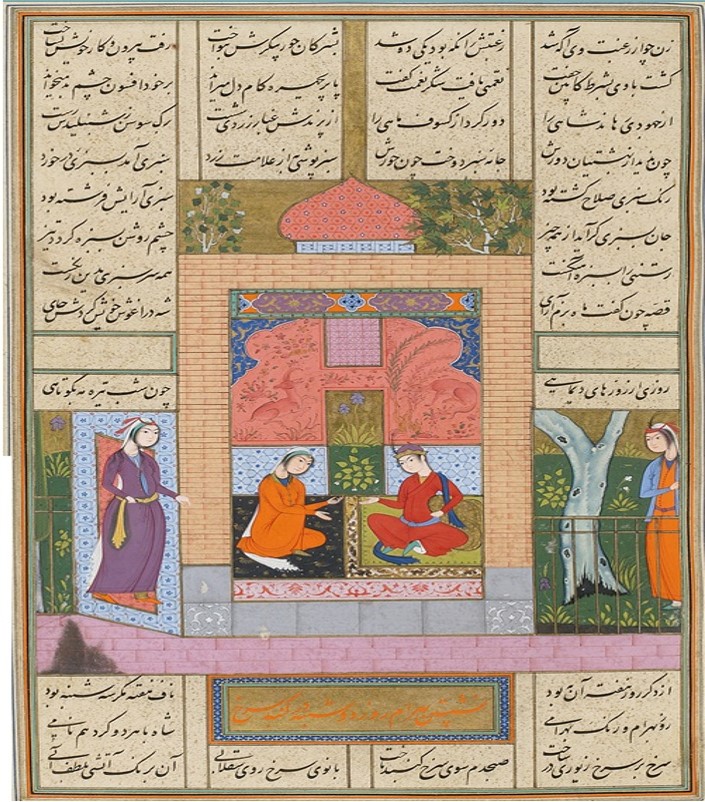

The plot of a cruel princess who asks riddles from her suitors appears in the red pavilion. It takes place on Tuesday, the day of Mars. Dressed all in red, King Bahram visits the princess Nasrin, who wears crimson robes with hair like the colour of fire and skin whiter than snow. The whole interior of the pavilion is decorated in red, red carpets, roses, and serving red wine. The princess tells a story of a princess in a far-off place in Russia. She is beautiful, skilful in bow and arrow, and is more learned than any men. Her father begs her to marry one of the suitors but she declines. Eventually she leaves the palace and let a palace be built high on a mountain. Hidden swords are placed on the passageway leading to the palace so that they decapitate anyone walking on the road.

She would only marry the strongest and the most intelligent man who could enter this new palace, escaping the swords, and opening the locked door of the palace. Once in the palace, they had to answer four riddles asked by the princess. Would the suitor fail, he was immediately put to death. The princess orders to put her portrait on the city gate, challenging young men to suit her. Many suitors come but lose their lives. While her father weeps and shows pity on their deaths, the princess is cold and laughs, ordering to put the severed heads on the city gate. One day, a prince who is on a hunting expedition, arrives and falls deeply in love with the portrait of the princess. Realizing that this princess is ruthless, he goes to a sage, and asks him how to overcome the invisible swords, how to unlock the palace’s door, and how to answer the riddles. The wise sage says that death comes to everyone but love does not, so the prince should pursue his quest. The sage teaches him how to escape the swords, unlock the door, and answer the four riddles, giving him equipment. The prince succeeds to come into the palace’s garden, a desolate court without any trees and flowers. After long waiting, a maiden comes to him and asks him to go back to her father’s palace and wait for the princess to come and ask him the riddles. The prince goes back. At seeing the prince, people rejoice and remove the portrait of the princess and the skulls of suitors from the city gate. People prepare a feast, drink wine, dance and play music. After waiting for two days, on the third day the princess comes. While smiling, she removes two pearls from her ears and gives them to the prince, asking him what these gifts mean. The prince gives her three pearls that the wise sage had given him. Then he orders courtiers to bring a scale and puts these three pearls on one side and the two pearls on the other. They were equal in weight. The prince answers: “if, as the scholars say, life is but two days long, here is your life and mine. And here is yet another life, which is our life together, when we are made one by love.” (Chelkowski, 1975: 93) Afterwards, the princess calls for a mortar, grinding the pearls and adding sugar to them. She then throws them into a cup and gives them to the prince, asking him what he thinks of such a gift. He brings forth a flask of milk that the sage had given him and pours it to the cup and asks the princess to drink. The powdered pearls remain in the bottom of the cup. Afterwards, the princess gives the prince her precious ring and asks him what he thinks of the gift. The prince gives her a luminous perfect pearl. Finally, the princess unfastens her necklace and gives the prince a pearl exactly the same as the one the prince had given her, asking him what he thinks of the gift. The prince brings forth a glass bead and a string and puts the bead between the pearls, saying to the princess, may our love guard us against evil spirit. In this way he answers all questions.

Rehearsal footage of Turan Dokht, created by director Miranda Lakerveld and composer Aftab Darvishi.

In Nezami’s account, the prince does not ask riddles, and the riddles asked by the princess are not verbal questions. But in a second source of the story, we find several verbal riddles asked by both the prince and the princess. This second source is Javāmiʿ al-hekāyāt (‘Collection of Stories’) by Mohammad ʿAufi (ca. 1170-1232). ʿAufi’s story is short and it mostly concentrates on ten riddles presented by the princess. ʿAufi places the story in the Roman empire and emphasizes the cruelty of the princess as she kills 42 suitors who failed to answer the riddles. Here a prince falls in love with the cruel Roman princess by hearsay. He goes to her palace and challenges her. The princess’s father shows big sympathy with him. The majority of the riddles are related to cosmogony, religion and ethics. These are riddles to test the intelligence of a young person, which often appear in Persian epic poetry. After answering all of these questions, the prince asks a riddle from the princess, and gives her one day to solve it. In ʿAufi’s retelling, the princess goes to her mother for advice. She convinces her to marry the prince. Several of the motifs Nezami used also appear in ʿAufi’s story such as putting severed heads on the city gate, the king who deeply sympathizes with the young men vising his daughter, and falling in love either through hearsay or portrait.

Bahram vising the red pavilion (Leiden Medievalists Blog).

Another source of the story, which is written much later, is a longer story based on ʿAufi’s narrative. It is here that we see the setting is changed to China. In Persian romantic tradition, including folklore, China is famous for handsome girls, and a Persian prince often goes in quest of finding his marriage partner in China. In this quest story, after much hardship the prince arrives in China and falls in love with a princess through hearsay. An old woman tells him about the cruel behaviour of the princess, imploring him to forget her. The prince goes to the princess’s palace, and she asks him riddles in four consecutive days. The prince answers them all. On the last day, the prince presents a riddle to the princess and gives her one day to guess an answer. Unable to solve the riddle, she sends beautiful maidens to the prince to make him drunk, and to seduce him to dig out the answers. One of the maidens brings the drunken prince to bed and discovers the answer to the riddle. Before making love, the maiden tricks him, running away while leaving behind her cloths. When the next day, the prince comes to the palace to receive the answer from the cruel princess, who haughtily says to the prince that she will kill him, he says, “last night I was on a hunting expedition. I chased a bird. I caught her, prepared her for consummation, but she flew away, yet I have her wings and feathers still with me.” This answer convinces the princess of his intelligence and agrees to marry him.

This longer version of the story was translated into Turkish under the title of Ferec baʿd al-shedda (‘Relief after Hardship’). In the Persian stories, the actual names of the prince and the princess are not mentioned, but in this Turkish translation, Calaf appears, which is a corruption of Khalaf meaning ‘successor,’ ‘child,’ or ‘offspring.’

François Pétis de La Croix (1653-1713) translated the story very freely into French and added Chinese colouring to it. The European versions of the riddle princess starts from this period. Carlo Graf Gozzi (1720-1806) had adapted several oriental stories, among which this particular narrative. Puccini’s libretto is written by Giuseppe Adami (1878-1946) and Renato Simoni (1875-1952). Puccini knew the story already through the play written by Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805), which was based on Gozzi’s version.

Riddles asked by Puccini’s Turandot.

It is fascinating to see how an anecdote, which comes probably from an oral Persian background, developed to several complex stories which all emphasize the riddling elements through a powerful, handsome and cruel princess, who tests the intelligence and physical prowess of her suitors.

Answers to riddles:

- the Red Sea

- a name

Literature

Chelkowski, P., “Āyā operā-ye Turandot-e Puccini bar asās-e kushk-e sorkh-e Haft Peykar- e Nezāmi ast?” (Is Puccini’s ‘Turandot’ based on the Red Pavilion of Nezami’s Haft Peykar?), in Iranshenasi, 1991, pp. 715–721.

Dabashi, H., Persophilia: Persian Culture on the Global Scene, Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2015.

Marzolph, U. & R. van Leeuwen, The Arabian Nights: Encyclopedia, Santa Barbara: ABC CLIO, 2004.

Marzolph, U., Relief after Hardship: The Ottoman Turkish Model for The Thousand and One Days, Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press, 2017 (I had no access to this book).

Mogtader, Y. & G. Schoeler, Turandot: Die persische Märchenerzählung, Edition, Űbersetzung, Kommentar, Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag, 2019.

Seyed-Gohrab, A.A., Courtly Riddles: Enigmatic Embellishments in Early Persian Poetry, Amsterdam, Rozenberg Publishers / West Lafayette, Indiana, Purdue University press, 2008. (republished in 2010 at Leiden University Press)

Seyed-Gohrab, A.A., Laylī and Majnūn: Love, Madness and Mystic Longing in Nezāmi’s Epic Romance, Leiden / Boston: E.J. Brill, 2003.

Yohannan, J.D., Persian Poetry in England and America: a 200-Year History, New York: Caravan Books, 1977.[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]