The article below on “Artifacts Show Sophistication of Ancient Nomads” was first published in the New York Times in March 12, 2014. Kindly note that while the article is highly informative, it does make one misleading statement:

“As the nomads left no writing, no one knows what they called themselves“

This leads the reader to the erroneous impression that the identity and language of the ancient Eurasian nomads are unknown. Linguists have long known of the identity and language of the Scythians and their Sarmatian-Alan successors. Below are a select number of quotes from prominent scholars in the field:

- Channon & Hudson: “… Scythians and Sarmatians were of Iranian origin” (1995, p.18); Channon, J. & Hudson, R. (1995). The Penguin Historical Atlas of Russia. London: Penguin Books.

- Sulimirski identifies Scythians & Sarmatians “…akin to the ancient Medes, Parthians and Persians” (1970, p.22); Sulimirski, T (1970), The Sarmatians. Thames & Hudson, London.

- Cotterell: “…the close relations of the Scythians with the Persians is perhaps most illustrative…in the…fact that…Scythians and Persians spoke closely related languages and understood each other without translators” (2004, p.61); Cotterell, A. (2004). The Chariot: The Astounding Rise and Fall of the World’s First War Machine. London, England: Pimlico.

- Newark notes that the Scythians were: “…Indo-European in appearance and spoke an Iranian tongue which bought them more closely to the Medes and Persians” (Newark, 1998, p.6); Newark, T. (1998). Barbarians.

- Mariusz & Mielczarek: “The Sarmatians…spoke an Iranian language similar to that of the Scythians and closely related to Persian” (2002, p.3); Mariusz, R. & Mielczarek,R. (2002). The Sarmatians: 600 BC-450 AD. Osprey Publishing.

====================================

Ancient Greeks had a word for the people who lived on the wild, arid Eurasian steppes stretching from the Black Sea to the border of China. They were nomads, which meant “roaming about for pasture.” They were wanderers and, not infrequently, fierce mounted warriors. Essentially, they were “the other” to the agricultural and increasingly urban civilizations that emerged in the first millennium B.C.

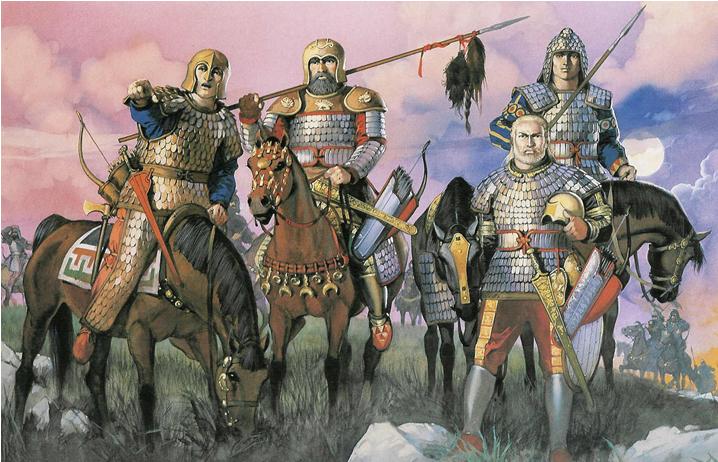

A reconstruction of the European Scythians (the Saka Paradraya) by the late Angus McBride. As noted by Cotterell “:..the close relations of the Scythians (Saka) with the Persians is perhaps most illustrative…in the … fact that the Scythians and Persians spoke closely related languages and understood each other without translators” (Cotterell, A. The Chariot: The Astounding Rise and Fall of the World’s First War Machine. London, England: Pimlico, 2004, p.61).

A reconstruction of the European Scythians (the Saka Paradraya) by the late Angus McBride. As noted by Cotterell “:..the close relations of the Scythians (Saka) with the Persians is perhaps most illustrative…in the … fact that the Scythians and Persians spoke closely related languages and understood each other without translators” (Cotterell, A. The Chariot: The Astounding Rise and Fall of the World’s First War Machine. London, England: Pimlico, 2004, p.61).

As the nomads left no writing, no one knows what they called themselves. To their literate neighbors, they were the ubiquitous and mysterious Scythians or the Saka, perhaps one and the same people. In any case, these nomads were looked down on — the other often is — as an intermediate or an arrested stage in cultural evolution. They had taken a step beyond hunter-gatherers but were well short of settling down to planting and reaping, or the more socially and economically complex life in town.

But archaeologists in recent years have moved beyond this mind-set by breaking through some of the vast silences of the Central Asian past.

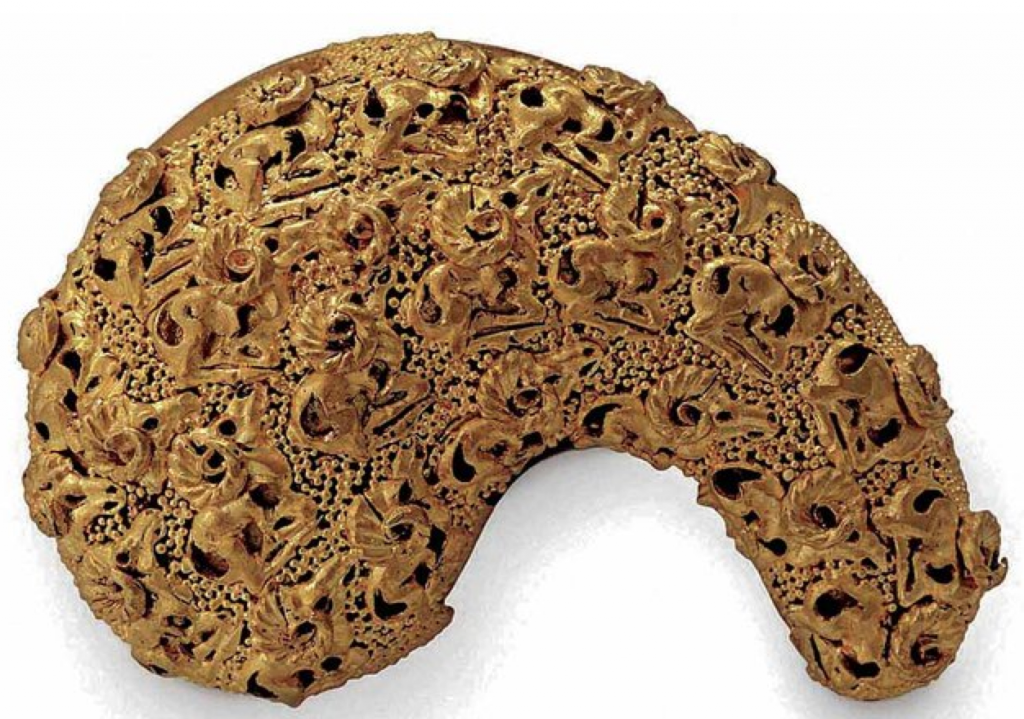

A teardrop-shaped gold plaque is one of the objects that shows the strong social differentiation of nomad society (Source: New York Times).

A teardrop-shaped gold plaque is one of the objects that shows the strong social differentiation of nomad society (Source: New York Times).

These excavations dispel notions that nomadic societies were less developed than many sedentary ones. Grave goods from as early as the eighth century B.C. show that these people were prospering through a mobile pastoral strategy, maintaining networks of cultural exchange (not always peacefully) with powerful foreign neighbors like the Persians and later the Chinese.

Some of the most illuminating discoveries supporting this revised image are now coming from burial mounds, called kurgans, in the Altai Mountains of eastern Kazakhstan, near the borders with Russia and China. From the quality and workmanship of the artifacts and the number of sacrificed horses, archaeologists have concluded that these were burials of the society’s elite in the late fourth and early third centuries B.C. By gift, barter or theft, they had acquired prestige goods, and in time their artisans adapted them in their own impressive artistic repertory.

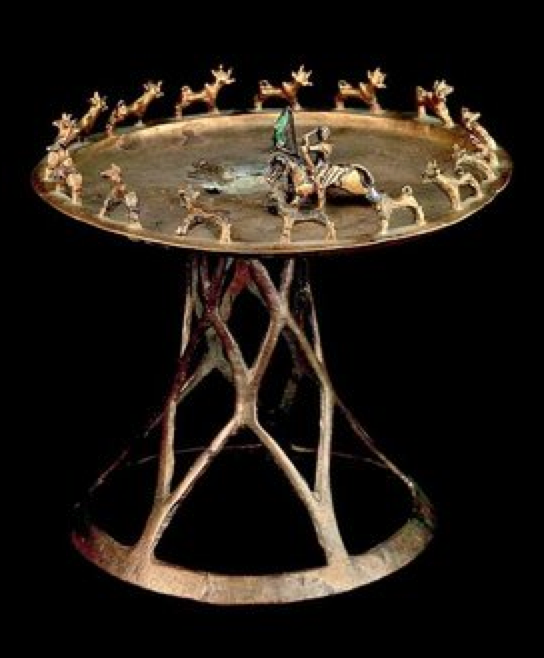

A copper alloy tray on a conical stand with an archer at center (Source: New York Times).

A copper alloy tray on a conical stand with an archer at center (Source: New York Times).

Almost half of the 250 objects in a new exhibition, “Nomads and Networks: The Ancient Art and Culture of Kazakhstan,” are from these burials of a people known as the Pazyryk culture. The material, much of which is on public display for the first time, can be seen at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at New York University, on loan from Kazakhstan’s four national museums. Two quietly spectacular examples are 13 gold pieces of personal adornment, known as the Zhalauli treasure of fanciful animal figures; and the Wusun diadem, a gold openwork piece with inlaid semiprecious stones from a burial in the Kargaly Valley in southern Kazakhstan. The diadem blends nomad and Chinese characteristics, including composite animals in the Scytho-Siberian style and a horned dragon in an undulating cloudscape.

Artifacts from recent kurgan digs include gold pieces; carved wood and horn; a leather saddle; a leather pillow for the deceased’s head; and textiles, ceramics and bronzes. Archaeologists said the abundance of prestige goods in the burials showed the strong social differentiation of nomad society.

An embroidery of a winged bull (Source: New York Times).

An embroidery of a winged bull (Source: New York Times).

Jennifer Y. Chi, the institute’s chief curator, writes in the exhibit’s catalog, published by Princeton University Press, that the collection portrays “a world of nomadic groups that, far from being underdeveloped, fused distinct patterns of mobility with apparently sophisticated ritual practices expressive of a close connection to the natural world, to complex burial practices and to established networks and contacts with the outside world.”

Walking through the exhibit, Dr. Chi pointed to nomad treasures, remarking:

“The popular perception of these people as mere wanderers has not caught up with the new scholarship.”

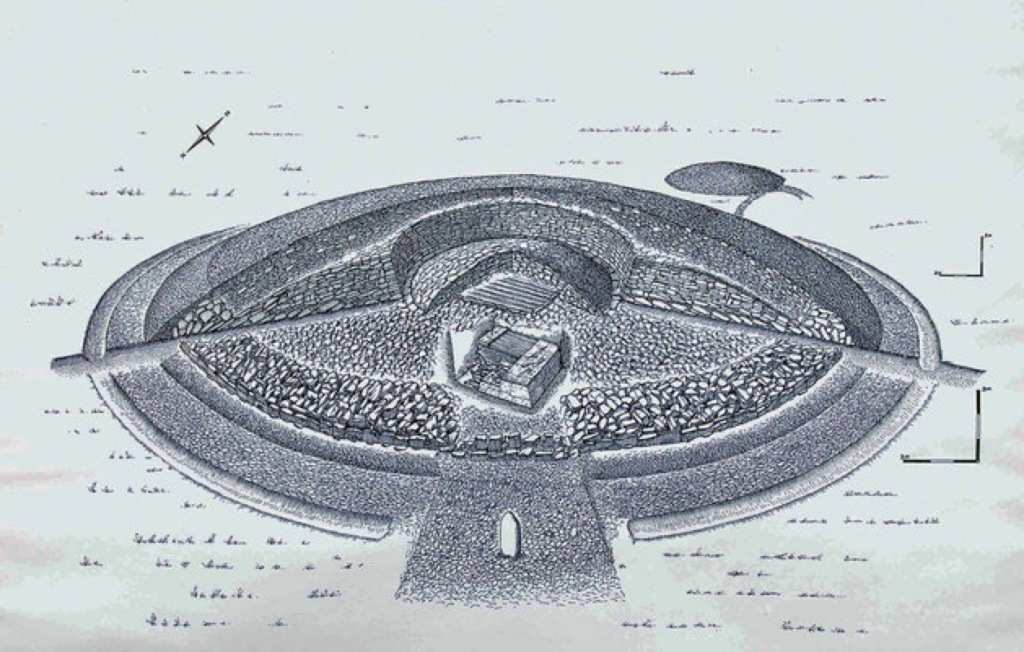

Excavation at the Altai kurgans, near the village of Berel, was begun in 1998 by a team led by Zainolla S. Samashev, director of the Margulan Institute of Archaeology, on a natural terrace above the Bukhtarma River. Some work had been done there by Russians in the 19th century. But the four long lines of kurgans, at least 70 clearly visible, invited more systematic exploration.

Of the 24 Berel kurgans investigated so far, Dr. Samashev said in an interview, the two he started with were among the largest. The mounds, about 100 feet in diameter, rise about 10 to 15 feet above the surrounding surface. The pit itself is about 13 feet deep and lined with logs. At the base of Kurgan 11, he said, the arrangement of huge stones let the cold air in but not out.

This and other physical aspects of the pits created permafrost, which preserved much of the organic matter in the graves — though looting long ago disturbed permafrost conditions. Still, enough survived of bones, hair, nails and some flesh to tell that some of the bodies had tattoos and had been embalmed. Hair of the buried men had been cut short and covered with wigs.

A drawing showing the construction of a Kurgan (Source: New York Times).

A drawing showing the construction of a Kurgan (Source: New York Times).

The Kazakh conservator of the artifacts, Altynbekov Krym, said that remains in several kurgans were a challenge. As noted by Krym:

“Everything was jumbled together, getting moldy almost immediately…took six years experimenting to create a new methodology to clean and preserve the material.”

Dr. Samashev said that his international crew, which is limited by climate to summer work, had excavated at least one kurgan a year. Several were burials of lesser figures. These were usually only a man and one horse. Kurgan 11 had a man who apparently met a violent death in his 30s; a woman who died later; and 13 horses, dressed in formal regalia before they were sacrificed.

So many horses, found in a separate section of the pit, affirmed the man’s lofty social status. Their leather saddles with embroidered cloth survived, as well as bridle and other tack decorated with plaques of real and mythical animals — like griffins, which had the body of a tiger or lion with wings and the head of a bird.

A feline face and stylized ornaments from horse tack, made of wood, tin and gold foil (Source: New York Times).

Soren Stark, an assistant professor of Central Asian art and archaeology at the N.Y.U. institute, said networks of contacts with the outside world were crucial to the political structure of the people throughout the Altai and Tianshan Mountains.

On the most basic level, they moved with the seasons by horse and camel, tending the flocks of sheep and goats that gave them the meat, milk, wool and hides of their pastoral economy. To make the most out of grasslands that were only seasonally productive, they went in small family groups into the highland meadows for summer grazing and returned to the lowlands in winter. They crossed broad plains to avoid overgrazing any one marginal pasture.

At their late autumn and winter campsites, herders assembled in large groups and engaged in tribal hunts and rituals. The exhibition includes bronze caldrons, presumably for preparing communal feasts, and several bronze stands, including one with a seated man holding a cup and facing a horse, that have the experts puzzled. Equally enigmatic are the symbols on rock faces that perhaps mark sacred places.

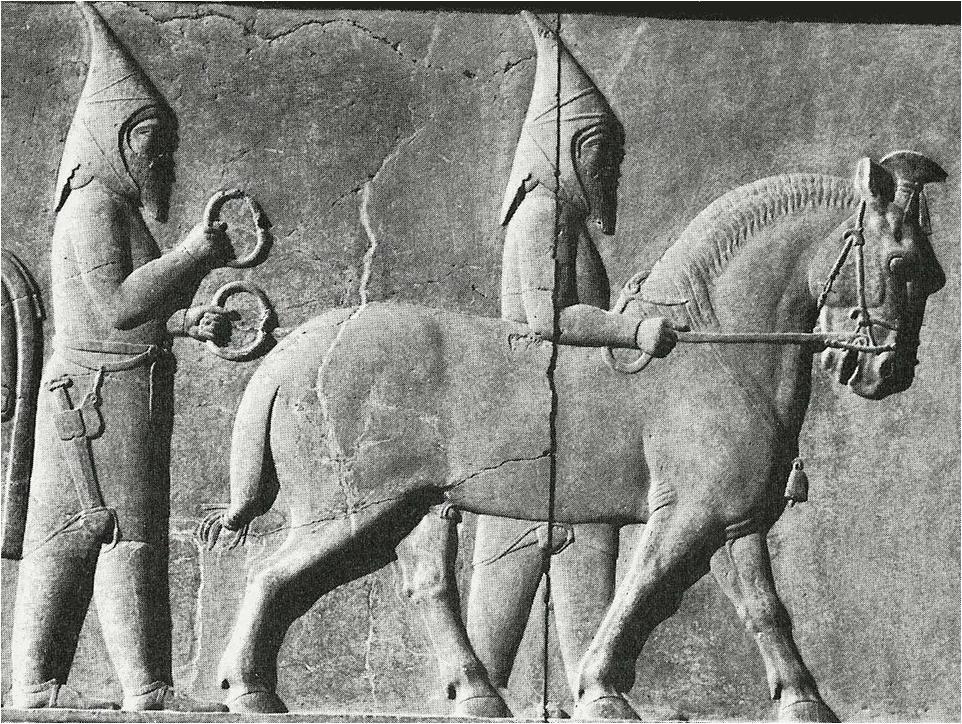

Saka Tigra-khauda (Old Persian: pointed-hat Saka/Scythians) as depicted in the ancient Achaemenid city-palace of Persepolis. It was northern Iranian peoples such as the Sakas (Scythians) and their successors, the Sarmatians and Alans, who were to be the cultural link between Iran and ancient Europe (Picture used in Kaveh Farrokh’’s lectures at the University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division and Stanford University’s WAIS 2006 Critical World Problems Conference Presentations on July 30-31, 2006).

Saka Tigra-khauda (Old Persian: pointed-hat Saka/Scythians) as depicted in the ancient Achaemenid city-palace of Persepolis. It was northern Iranian peoples such as the Sakas (Scythians) and their successors, the Sarmatians and Alans, who were to be the cultural link between Iran and ancient Europe (Picture used in Kaveh Farrokh’’s lectures at the University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division and Stanford University’s WAIS 2006 Critical World Problems Conference Presentations on July 30-31, 2006).

From the camps, parties of mounted warriors set out to raid settlements, both to supplement their meager resources and to obtain luxury goods coveted by their leaders. Dr. Stark said the nomad elite considered such goods necessities to be displayed and distributed to key followers “to build up and sustain their political power.”

As their networks widened, foreign influences, notably Persian, began to appear in nomadic artifacts from the sixth to the fourth centuries B.C. The griffin, for example, originated in the West by way of the Persian Empire, centered in what is now Iran; the nomads modified it to have two heads of birds of prey topped by elk horns.

A gold and turquoise plaque of a snow leopard mask consisting of two facing ibex heads and flying bird (8th to 7th centuries B.C.; Height 1.56 centimeters; width 2.48 centimeters; depth 0.2 centimeters) (Source: New York Times).

A gold and turquoise plaque of a snow leopard mask consisting of two facing ibex heads and flying bird (8th to 7th centuries B.C.; Height 1.56 centimeters; width 2.48 centimeters; depth 0.2 centimeters) (Source: New York Times).

Beginning in the third century B.C., Chinese luxury items, like the Wusun diadem, appeared in nomad burials, mainly associated with Han dynasty. According to Chinese accounts, the Wusun nomads may have furthered contacts between Central Asian nomads and Han China, at the time expanding westward and in need of horses in its campaign against borderland rivals.

For all their networking, the nomads of the first millennium B.C. never failed to apply imaginative touches to the foreign artifacts they acquired. Dr. Chi, the curator, said the nomads transformed others’ fantastic animals into even more fantastic versions: boars curled in teardrop shapes and griffins that seemed to change their parts in a single image.

By these enigmatic symbols, a prewriting culture communicated its worldview from a vast and ungenerous land that it could never fully tame — any more than these people of the horse were ever ready to settle down.