The article “The Parthian Wars of Septimius Severus” was published by Weapons and Warfare on July 17, 2019. Kindly note that: (a) the text printed below has been edited from the original Weapons and Warfare article (b) excepting one image, none of the other images do not appear in the original Weapons and Warfare article and (c) none of the captions accompanying the images below appear in the original Weapons and Warfare article.

Readers further interested in the military history of the Parthians are referred to the following sources:

- Military History and Armies of the Parthians

- Karamian, Gh., & Farrokh, K. (2019). A unique Parthian sword. HISTORIA I ŚWIAT, 8, pp.211-214.

- Karamian, Gh., Farrokh, K., Kiapi, M.F., Nemati, H. (2018). Graves, crypts and Parthian weapons excavated from the gravesites of Vestemin. HISTORIA I SWIAT, No.7, pp. 35-70.

- Farrokh, K., Karamian, Gh., Kubic, A., & Oshterinani, M.T. (2017). An Examination of Parthian and Sasanian Military Helmets. In “Crowns, hats, turbans and helmets: Headgear in Iranian history volume I” (K. Maksymiuk & Gh. Karamian, Eds.), Siedlce University & Tehran Azad University, pp.121-163.

- Farrokh, K., Karamian, Gh., Delfan, M., Astaraki, F. (2016). Preliminary reports of the late Parthian or early Sassanian relief at Panj-e Ali, the Parthian relief at Andika and examinations of late Parthian swords and daggers. HISTORIA I ŚWIAT, No.5, pp. 31-55.

- Farrokh, K., Karamian, Gh. & Kubik, A. (2016). An Examination of Parthian and Sassanian Military Helmets (2nd century BCE – 7th century CE).

- Syvänne, I. (2017). Parthian cataphract vs. the Roman army 53 BC-AD 224. HISTORIA I ŚWIAT, no.6, pp. 33-54.

- Camel Cataphracts

- Counting Arrows: How the Parthian Empire Counted its Dead

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

In 216 CE, Emperor Caracalla (r. 198-217 CE; co-ruler with Septimius Severus in 198-211 CE), like his father Septemius Severus (r. 198-211 CE; co-ruler with Geta in 209-211 CE), resolved on a Parthian campaign. This took him across the Tigris to Arbela before his murder near Edessa in 217. Caracalla’s short-lived successor Marcus Opellius Macrinus (r. 217-218 CE) met with defeat at the hands of the Parthian king Ardavan (Artabanus) IV at Nisibis.

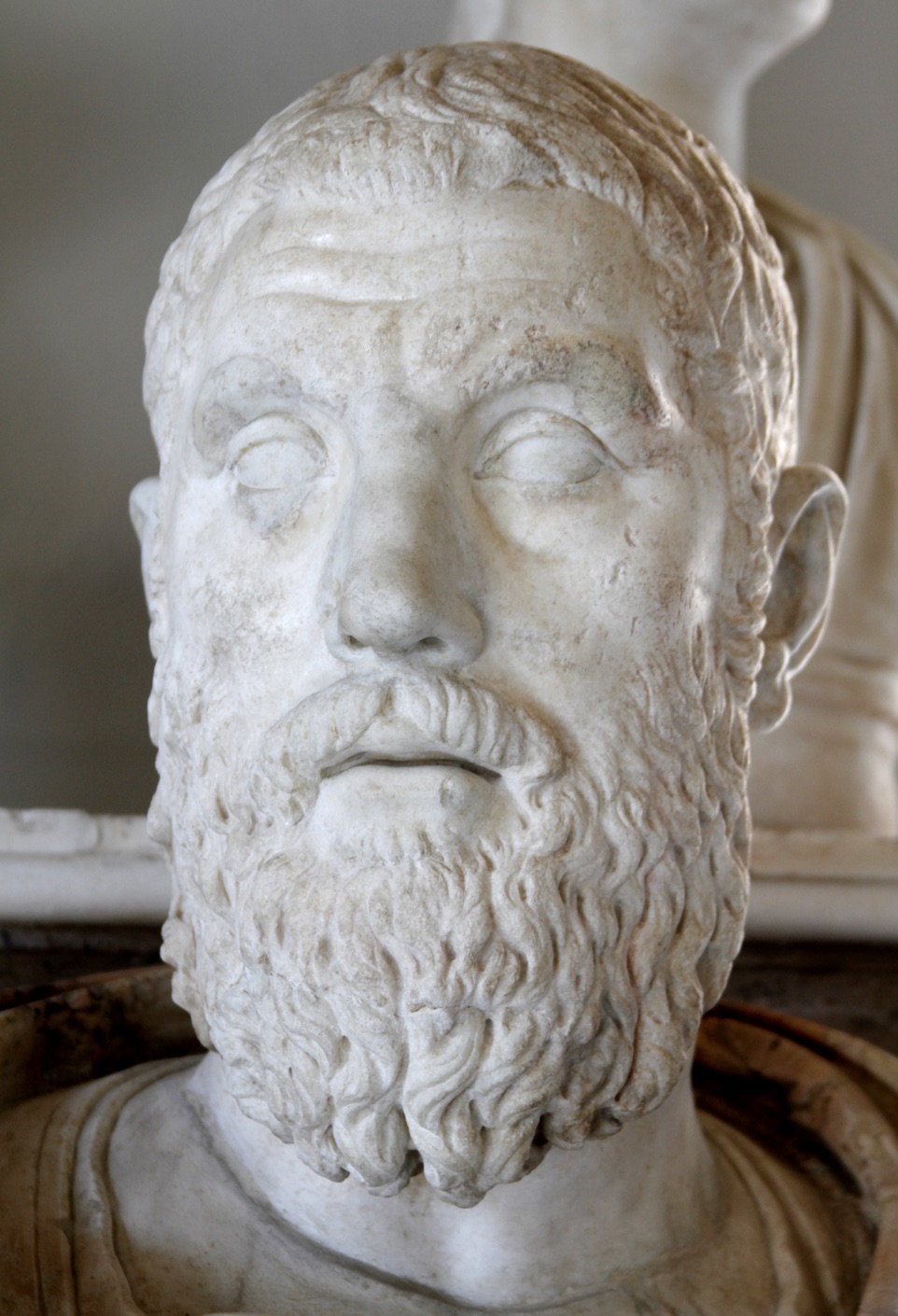

Bust of Marcus Opellius Severus Macrinus Augustus at the Palazzo Nuovo, Musei Capitolini in Rome (Source: José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro in Public Domain). Macrinus’ reign was ephemeral, having ruled for just a year in 217-218 CE.

After Caracalla’s assassination, his successor Macrinus immediately announced that his predecessor had done wrong by the Parthians and restored peace. In 218, after a battle fought at Nisibis during which both sides suffered heavy losses, a treaty was signed. According to Herodian, the Roman emperor Macrinus was delighted about having won the Iranian opponent as a reliable friend.

A recreation of the possible appearance and crown of Ardavan (Artabanus) IV (r. 213– 224 CE) (Source: Eranshahr) based on a numismatic (coin) portrait of Ardavan IV minted in Hamadan (Source: CNG (Classical Numismatic Group) in Public Domain).

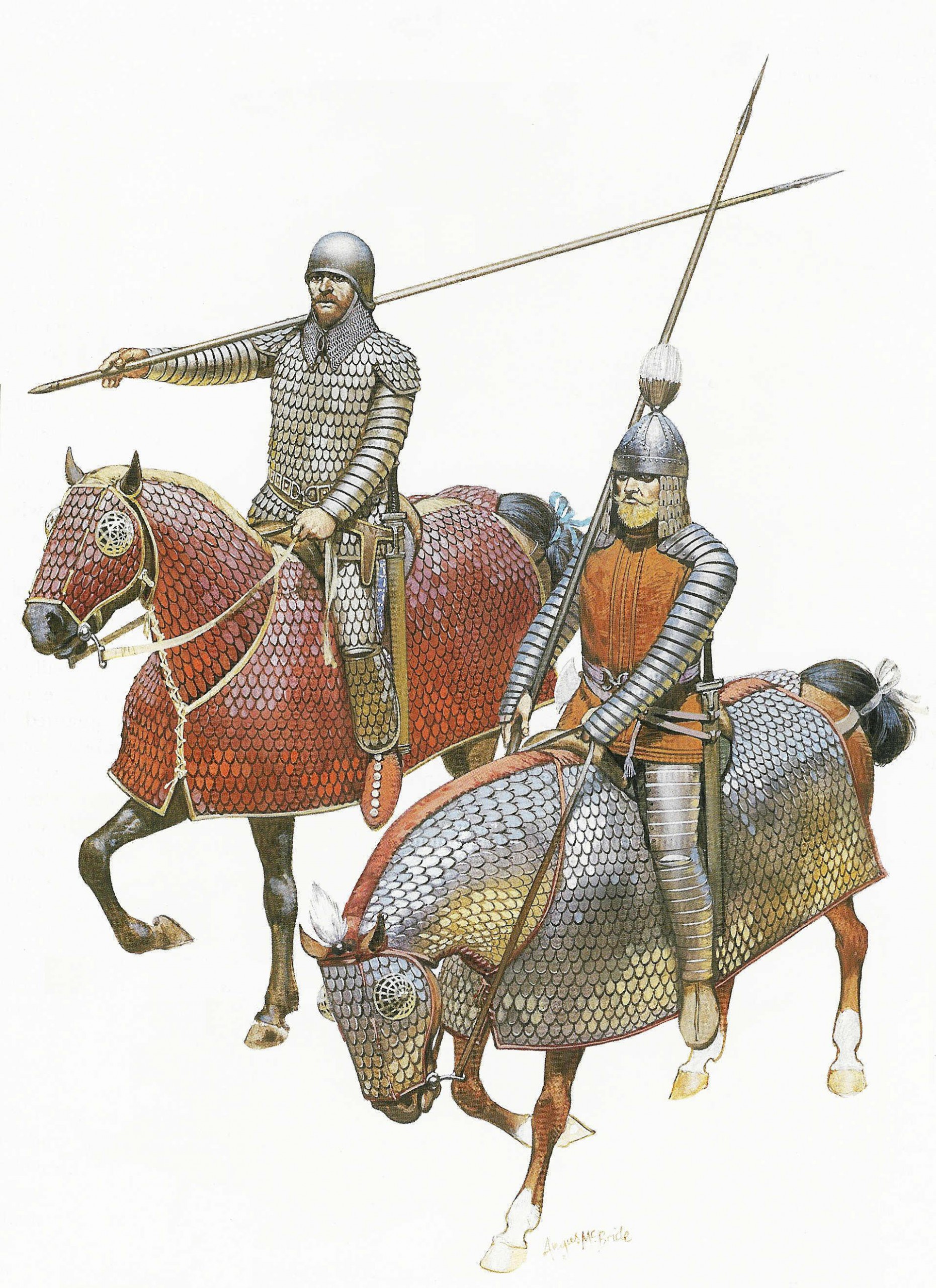

Near the city of Nisibis in Mesopotamia, an army led by Parthian King Ardavan (Artabanus) IV clashed with the legions of Emperor Macrinus. Following a skirmish between opposing troops over control of a water source, the two armies assembled for battle. The Parthian host consisted of large formations of heavy cavalry – both clibanarii and cataphracti – light mounted bowmen and a contingent of armoured camel riders called dromedarii. Macrinus readied his army for battle across the plain: the legions deployed in the centre, with cavalry and Moorish troops placed on the flanks. Arrayed at intervals within the central formation were Moroccan auxilia.

Reconstruction by Peter Wilcox and the late historical artist, Angus McBride of Parthian armored knights as they would have appeared in 54 BCE (Picture Source: Osprey Publishing).

Once battle was joined, the Parthian heavy horse and mounted archers inflicted severe casualties on the Roman infantry, while the legionaries and light troops proved superior in all hand-to-hand action. As the contest wore on, the Romans found themselves increasingly at a disadvantage against the speed and manoeuvrability of the enemy cavalry. In an effort to disrupt these incessant attacks, the legions feigned retreat at one point so as to draw the horsemen onto ground littered with caltrops and other devices designed to cripple the horses. Fighting continued unabated until dusk. Battle resumed the next morning and lasted all day, but again ended at nightfall with no clear victor. On the third day, Artabatus attempted to use his superior numbers of cavalry to encircle the Roman formation by means of a double envelopment, but Macrinus extended his battle-line in order to thwart the Parthians’ efforts. Toward late afternoon, the Roman emperor sent envoys to treat for peace, which was readily granted by the king. Artabatus afterward returned to Persia with his army, and Macrinus and his forces withdrew to the city of Antioch in Syria. To deter a resumption of hostilities, Macrinus presented the Parthian ruler with gifts amounting to 200 million sesterces.

Parthian Horse archers engage the Roman legions as they attempt to invade Persia. Unlike the Achamenid-Greek wars where Achaemenid arrows were unable to penetrate Hellenic shields and armor, Parthian archery was now capable of penetrating Roman armor and shields (Picture Source: Antony Karasulas & Angus McBride).

Like most Parthian armies, the forces under Ardavan consisted mostly of cavalrymen and archers. On the other hand, the Parthian army at Nisibis was unique in that it contained a contingent of a rare cataphract–type of warriors who were mounted not upon horses, but rather camels instead. In his History of the Roman Empire, Herodian first mentions the distinctive troops in the events leading up to the battle:

Artabanus (Ardavan IV) was marching toward the Romans with a huge army, including a strong cavalry contingent and a powerful unit of archers and those cataphracts who hurl spears from camels.

Parthian cataphract lancers attack the Roman lines during the battle of Nisibis in 217 (Source: Weapons and Warfare). Despite their successes, the camel’s feet proved highly vulnerable Roman caltrops that had been strewn on the battlefield.

The camel cataphracts fought with either spears or lances, and both riders and mounts wore extensive armour like the traditional cataphracts who rode horses. Along with the legionaries, the Roman army also included contingents of light infantry and Mauretanian cavalrymen. The fighting between the two ancient superpowers was brutal and lasted for three long days. Herodian recorded how deadly the Parthian warriors, including the camel cataphracts, were on the first day of the fighting, yet he also described how the Romans eventually managed to gain the upper hand:

The barbarians inflicted many wounds upon the Romans from above and did considerable damage by the showers of arrows and the long spears of the cataphract camel riders. But when the fighting came to close quarters, the Romans easily defeated the barbarians; for when the swarms of Parthian cavalry and hordes of camel riders were mauling them, the Romans pretended to retreat and then they threw down caltrops and other keen–pointed iron devices. Covered by the sand, these were invisible to the horsemen and the camel riders and were fatal to the animals. The horses, and particularly the tender–footed camels, stepped on these devices and, falling, threw their riders. As long as they are mounted on horses and camels, the barbarians in those regions fight bravely, but if they dismount or are thrown, they are very easily captured; they cannot stand up to hand–to–hand fighting. And, if they find it necessary to flee or pursue, the long robes which hang loosely about their feet trip them up.

However, with the coming of night and no clear victor to the battle, the two armies retreated to their camps to rest for the night. The second day of the fighting ended in a stalemate as well. The third day of the battle, however, decided the outcome when the Parthians changed their tactics to try and fully envelope the numerically inferior Roman force. In response to the encircling attempts of the Parthian soldiers, the Romans extended their own lines to compensate for the extended Parthian front. However, the Parthians were able to exploit the weakened thinner lines of the Romans and achieve a great victory. Knowing he had lost the battle, Emperor Macrinus retreated and, soon after, his men fled to the Roman camp as well. Although the Parthians won the Battle of Nisibis, it was a Pyrrhic victory for Ardavan; the losses were heavy for both sides. Since the Parthian emperor desired peace almost as much as Macrinus, Ardavan accepted only a substantial payment in return for a cessation of hostilities, as opposed to the territory he previously demanded.

Parthian cavalry and banners (Picture source: Farrokh, 2007, page 130, hadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War-Персы: Армия великих царей-سایههای صحرا– these drawings originally appeared by Zoka in the 2,500 Year Celebrations of the Persian Empire in 1971).

Although Emperor Macrinus was quickly defeated, executed and replaced by one of his rivals, Elagabalus (r. 218-222), in 218, the Roman Empire continued to persist for centuries following its defeat at Nisibis. The Parthian Empire, on the other hand, became even weaker after its conflict with Rome and continued on its steady decline.

Revolts from within the empire continued to plague Ardavan so he could not sit back and enjoy his success over the Romans. In 220, the leader of the Sassanian Persians, Ardashir, managed to break free from Parthian rule and exploit the weakness of the empire to extend his control over more and more land. The growing Sasanian challenge to the Parthians was developing, which may be reflected in the inability of Ardavan to press his victory in Mesopotamia. By 224, Ardavan met Ardashir on the field of battle and lost more than his life; the Parthian Empire collapsed shortly after his fall.

Ardashir I (r. 224-242 CE) in a lance-joust scene at Firuzabad which commemorates the great battle in which the House of Sassan overthrew the Parthians in 224 CE. Note the large hair bundle (Korymbos) on top of Ardashir I’s head (Picture source: Photo taken by Farrokh in August 2001 and shown in Kaveh Farrokh’s lectures at The University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division , Stanford University’s WAIS 2006 Critical World Problems Conference Presentations on July 30-31, 2006).

It was not until after the Sasanian overthrow of the Parthians was complete that Roman power in Mesopotamia and on the middle Euphrates would be seriously challenged. In place of the Parthians, a new Iranian state arose known as the Sassanian Empire. As the new supreme empire of the east, the armies of the Sassanians had some of the greatest warriors of the ancient world. Like its Parthian predecessor, the elite heavy cavalry of the Sassanian Empire were also cataphracts.