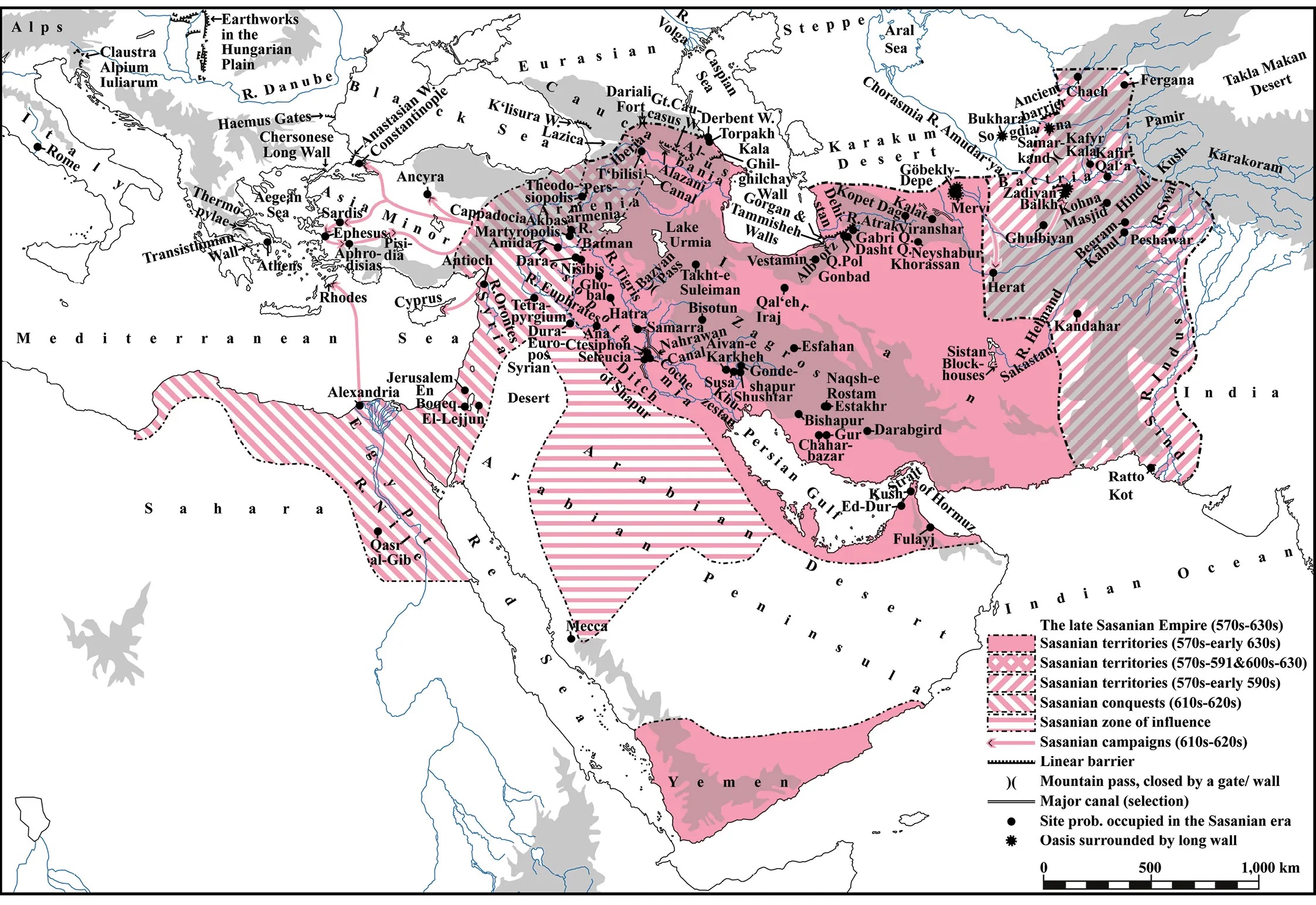

The article expostulates the archaeological research of the above scholars who have explored the backbone of the Sassanian Spāh’s fortification systems for the defence of the northeastern marches of the Sassanian Empire: this was the densest concentration of mega-fortresses in the late antique world, in the Gorgan and Tehran Plains of Iran.

Readers further interested in Sassanian military architecture are referred to the following articles:

=======================================================================

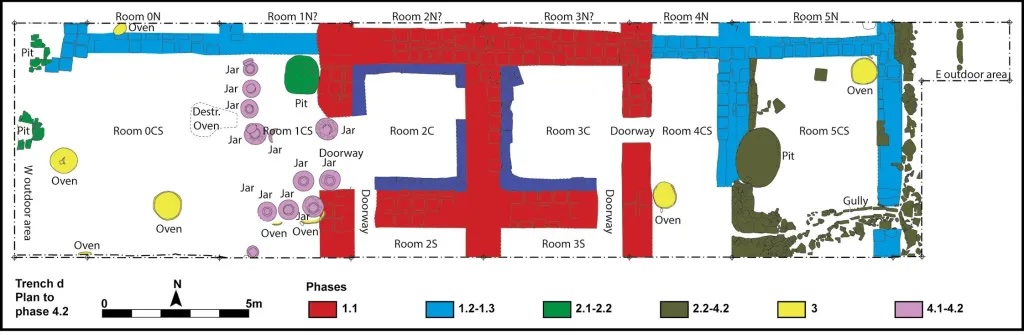

This plan shows features of the (mid?-) 6th century CE, with eight or nine separate ovens operational then in the area of our trench (not counting earlier and later fireplaces); two of the ovens were destroyed when one room was transformed into a storeroom (Image Source: Joint Project published in World Archaeology).

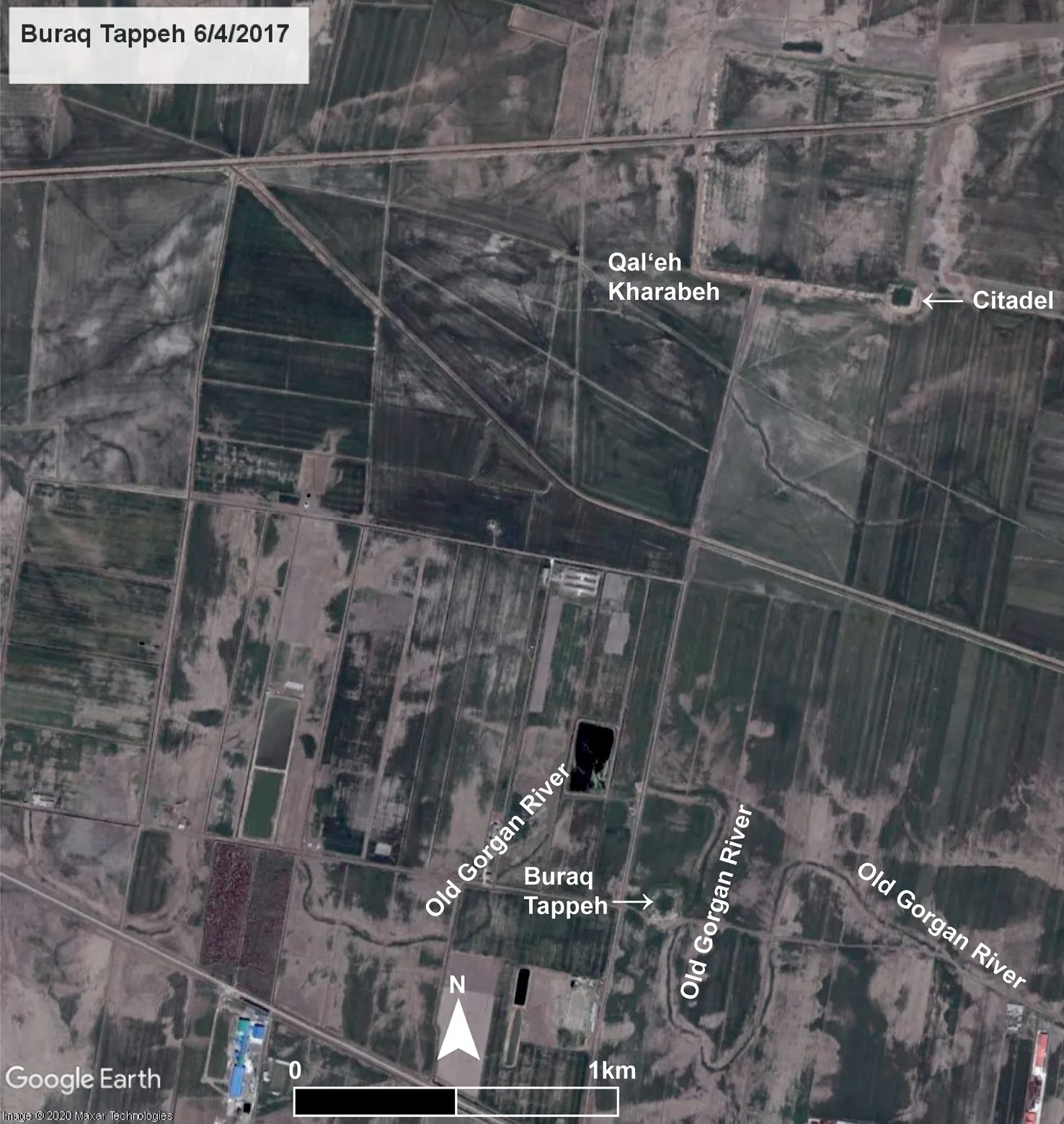

One of these forts, Buraq Tappeh (meaning ‘the White Mound’), was explored via geophysical survey and a sondage. This fort is smaller (c.0.5ha) than those on the Gorgan Wall. It was located some 4km south of the wall and once lay on a bank of the Gorgan River, which has subsequently changed its course. The fort’s architecture differs distinctly from that of its counterparts on the wall. Instead, Buraq Tappeh resembles a caravanserai, with accommodation lining the fort walls and a large courtyard at its heart. In both size and plan, it bears a striking resemblance to another Sasanian fort further upstream on the Gorgan River. Radiocarbon samples prove that Buraq Tappeh was occupied in the 5th to 6th centuries. Analysis of the pottery by Maria Daghmehchi suggests that while its occupation overlapped with that of the forts on the Gorgan Wall, activity at Buraq Tappeh started and ended earlier. The fort was probably part of a control line dating to the early 5th century. During later phases of occupation, Buraq Tappeh fell into disrepair, but was intermittently reoccupied. This can be explained by the stronghold now lying in the hinterland of the Gorgan Wall, making it surplus to requirements in normal circumstances, but offering a handy place of shelter during periods of crisis.

A drone photograph of Fort 26 (to the left of the road that follows the Gorgan Wall), by Davit Naskidashvili and the joint project (Image Source: Joint Project published in World Archaeology). Barracks filled much of the interior. Their decayed mud-brick walls are visible as yellow ridges, while subsidence of occupation deposits within has created small depressions in which water gathers and plants grow.

The Ancient World’s Largest Fortresses

While small forts like Buraq Tappeh were heavily defended and capable of housing a garrison of a few hundred soldiers, such a force was not sufficient to counter the threat facing the Gorgan Plain in the 5th century. Surviving sources attest that the area came under repeated attack by the ‘White Huns’ and associated groups. Several Sasanian kings personally led the efforts to defend the Gorgan Plain, which preserves evidence for the presence of massive field armies. Why was this region of such strategic significance? One reason is that the plain benefits from abundant rainfall, making it rich and fertile. The other is that it provides access to the Alborz mountain passes, which lead into the heartlands of northern Persia.

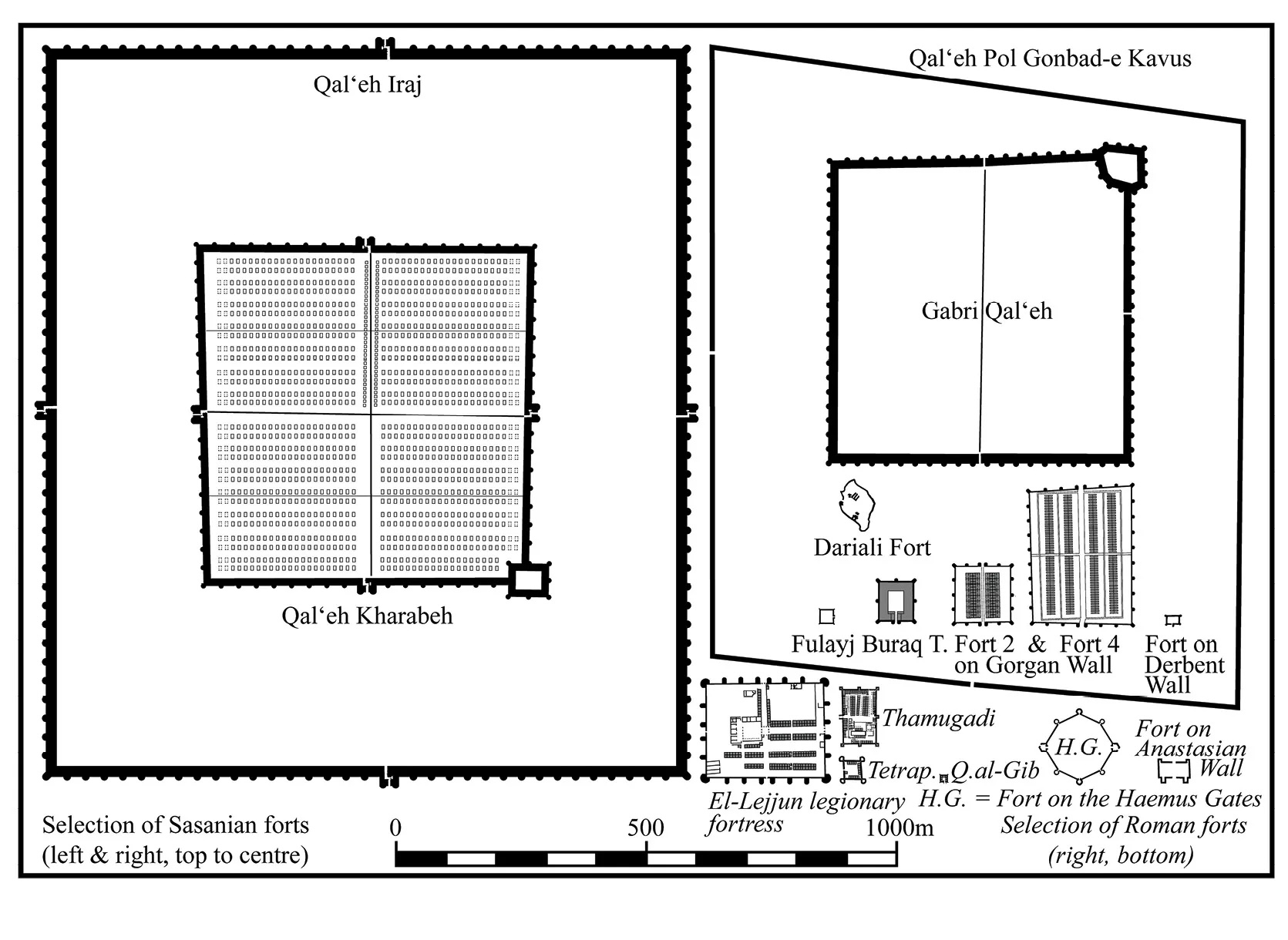

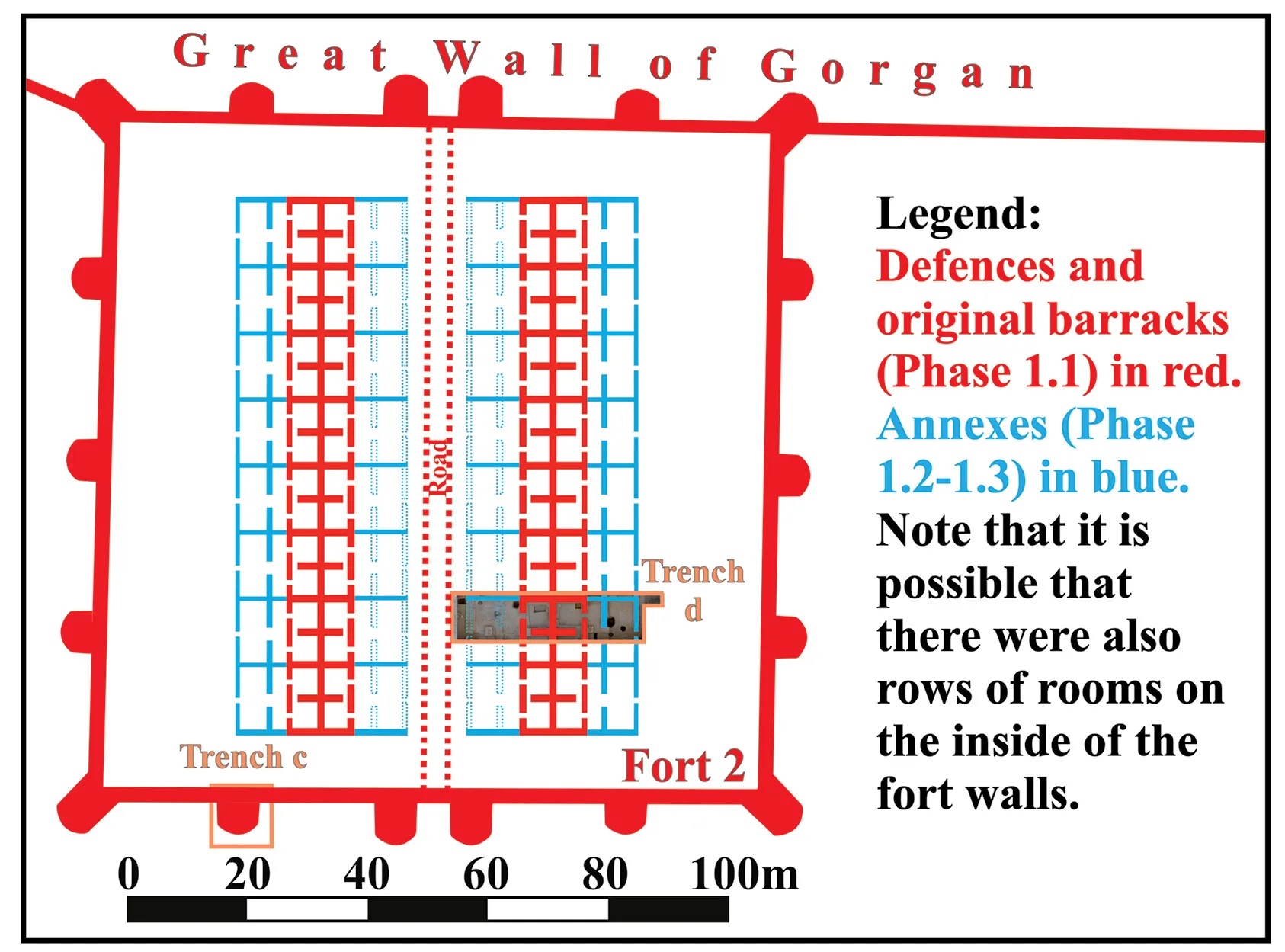

How could such vulnerable borderlands be defended? On the Gorgan Plain and elsewhere in the Sasanian Empire, a new type of fortification emerged, which was designed to keep mobile military reinforcements secure: geometric campaign bases protected by tall towered walls and a wide water-filled moat, with interiors that are mostly empty. The Gorgan Plain alone boasts seven such fortresses with internal areas of more than 35ha, as well as many more that are smaller or of uncertain date.

A 2.30m-deep bell-shaped storage pit, in which grain for the garrison would have been stored (Image Source: Joint Project published in World Archaeology). There were at least six storage pits in our trench, and perhaps up to 300 in Fort 2.

The large storage jars in a storeroom of the Fort 2 barracks (Image Source: Joint Project published in World Archaeology).

Perhaps the oldest fortress to be explored so far is a site with Sasanian and medieval pottery and the telling name Gabri Qal‘eh (‘the Zoroastrian Castle’). Two radiocarbon samples from the access causeway leading into the site indicate that it was built before the Gorgan Wall, with occupation reaching back to the 4th or early 5th century. Excavations within the interior have shown that it was ultimately transformed into a bustling medieval town occupied until the late 13th or 14th century. Perhaps it was the Black Death that brought about the final abandonment of this Sasanian foundation after a thousand years of occupation. But how can we know that it was a military fortress and not a town from the start? The relative abundance of Sasanian finds within the fabric of the access causeway proves that this element was not an original feature. Instead, it was only built after there was plenty of occupation debris around. Perhaps military-era deposits were then used as the building material for a causeway across the moat, at the same time that the fortress was being transformed into a town. Naturally, ease of access would be desirable for a town, while defensibility became a lower priority. This argument is admittedly speculative, but what is certain is that Gabri Qal‘eh is strikingly similar in plan and size to three other such compounds on the Gorgan Plain, and there is no evidence that any of the others was transformed into a town.

A drone photo of Fort 9, with the canal-lined Gorgan Wall visible on the right, by Davit Naskidashvili and the joint project (Image Source: Joint Project published in World Archaeology).

The best-known parallel for Gabri Qal‘eh is Qal‘eh Kharabeh (‘the Ruined Castle’), a site that is of crucial significance for establishing what purpose such compounds were designed to fulfil. Both magnetometer and aerial survey revealed that its interior was filled with neatly aligned double-rows of enclosures, each of them almost certainly dug around a tent. The wide access corridors in between each pair of double-rows provided plenty of space for tethering the soldiers’ horses. The tent enclosures evidently filled much or all of the eastern half of the vast interior (c.41ha), but oddly there is no trace of comparable features in the western half. Perhaps the enclosures date to a time when the compound was reoccupied by a unit that was half the size of the original garrison. If so, we can estimate that there were probably originally more than 1,000 tents in the interior – as well as probable additional housing in the fortress citadel and space in its 80 towers – which would mean the fortress could have comfortably sheltered at least 10,000 horsemen, and still have been less crowded than a Roman temporary camp. (A Roman camp of similar size would be suitable for a force of 20,000-30,000 foot soldiers.) Radiocarbon samples prove that Qal‘eh Kharabeh was occupied in the 5th or the first half of the 6th century, with the mid-5th century perhaps being the most likely construction date. This makes it possible that the garrison of this vast steppe compound oversaw construction of the Gorgan Wall, 2km to the north, but we cannot exclude the possibility that the fortress is a little earlier or a little later than the wall. Qal‘eh Kharabeh is so similar to Gabri Qal‘eh that it is hard not to believe that they were originally intended for the same purpose: both compounds are square with similar dimensions, both are neatly subdivided via central causeways, both boast a corner citadel, and both are defended by substantial tower-enforced walls and a massive moat.

Buraq Tappeh: a courtyard fort on the Old Gorgan River, near the Qal‘eh Kharabeh Fortress (Image Source: Satellite Image by Maxar technologies published in World Archaeology).. It was probably part of a chain of forts that preceded the Gorgan Wall.

By far the largest such compound on the plain is Qal‘eh Pol Gonbad-e Kavus (‘the Castle at the Bridge to Gonbad-e Kavus’, the nearby city), which covers some 125ha. A radiocarbon sample from the site is compatible with construction at any point between the CE 430s and early 600s, but a date after 528 is most likely. The fortress could have comfortably sheltered 30,000 mounted soldiers. Was it perhaps here that King Khusro I had his headquarters while fighting a war against the Turks (then the dominant northern power) in the 560s? During that episode, it was reportedly the strength of the Sasanian defences on the Gorgan Plain that prevented the Turkish army from making inroads into Sasanian lands. Archaeology has supported this assessment, by demonstrating that great care was indeed taken to make the Gorgan Wall as impermeable as possible, with even minor stream crossings secured by massive bridge barriers.

Gabri Qal‘eh, with its citadel and access causeway in the background, is the best-preserved and perhaps the earliest Sasanian fortress on the Gorgan Plain (Image Source: Joint Project published in World Archaeology). This drone image is by Davit Naskidashvili and the joint project (above).

The ruins are also imposing at ground level, as this view from Gabri Qal‘eh’s citadel over its north-eastern wall and substantial moat demonstrates (Image Source: Joint Project published in World Archaeology). Team members, involved in survey at the outer edge of the moat, visually demonstrate its impressive dimensions.

Northern Defence Nerve Centre?

The Sassanian Empire not only fortified its northern frontiers more heavily than any previous empire had done, it also had reinforcements available in strong fortresses to the south of the wall. These strongholds include the giant fortress of Qal‘eh Iraj (‘the Castle of Iraj’, a legendary ancient Persian hero) c.290-440km south-west of the wall, which covered 187ha. Its wall circuit is 5.5km long, and it boasts 148 towers. An estimated 828 rooms were embedded in the ramparts to accommodate the soldiers patrolling these walls. If occupied as densely as postulated for Qal‘eh Kharabeh, there would have been space for 40,000-50,000 horsemen. Qal‘eh Iraj has been explored over many years by Mohammadreza Nemati and Mehdi Mousavinia, and we excavated two further trenches jointly. Our samples suggest that the fortress was built in the early 5th century. Ostraca deciphered by Carlo Cereti attest to supplies of a various foodstuffs, as well as horses, spades, and spears – fascinating evidence that a well-organised, literate administration was in charge of logistical matters, just as in the Roman army. This mega-fortress was probably occupied into the late Sasanian era, and may have functioned as both a command centre and major military base for the field army, with a capability of dispatching tens of thousands of men to any conflict zone within range. It could also have intercepted any hostile force that succeeded in crossing the Gorgan Wall or the Empire’s Caucasian frontiers, before they reached the heartlands of the Empire. In this way, one of the Empire’s strongest fortresses was strategically placed at the crossroads of northern Persia, a position that is occupied today by nearby Tehran, the modern capital of Iran.

The Gorgan Wall crossed this small stream via a massive bridge, which survives to a height of 7.50m (Image Source: Joint Project published in World Archaeology).

An Economic and Military Powerhouse

The Empire’s northern defences were not only impressive in scale, but seem to have been remarkably effective, too. So far as we are aware, no invasion reached the Empire’s breadbasket in Mesopotamia and south-western Persia between the late 4th and early 7th centuries. Surveys suggest that the population in many parts of the Empire rose to levels never seen before, while new cities, such as Dasht Qal‘eh (‘the Large Flat Castle’) on the Gorgan Plain, were established at a time when urbanism was in severe decline across much of Europe.

Excavations in the south-east gate of Qal‘eh Iraj have yielded written documents (Image Source: Joint Project published in World Archaeology). The gate is flanked by massive projecting towers, overlooking a narrow zigzag gateway.

Economic prosperity and the strength of the Empire’s defences enabled it to prevail against a powerful Romano-Turkish coalition that threatened it on two fronts. The Sasanians even succeeded in temporarily conquering Syria and Egypt in the early 7th century, pushing the Roman/Byzantine Empire to the brink of annihilation. Eventually, like all other ancient and medieval empires, the Sasanians fell, but they had prospered for far longer than most other empires of a similar size. Remarkably, when the fatal attack finally came, it was via the less well defended frontiers in the south. The heavily fortified north was the last part of the Sassanian Empire to fall to the Islamic Caliphate.

Urbanism in the Sasanian Empire flourished: the city of Dasht Qal‘eh on the Gorgan Plain was established in the 5th century and had 6.5km-long city walls (Image Source: Joint Project published in World Archaeology). This drone image is by Davit Naskidashvili and the joint project.

FURTHER INFORMATION

We are very grateful to our wonderful team, to the European Research Council for funding our fieldwork, and to our colleagues at the Iranian Centre for Archaeological Research and the Research Institute of Cultural Heritage and Tourism for their kind support.

To find out more, see our full report:

SOURCES

Eberhard Sauer, University of Edinburgh; Jebrael Nokandeh, National Museum of Iran and RICHT; Hamid Omrani Rekavandi, ICHHTO; Mohammadreza Nemati, ICAR; and Mehdi Mousavinia, University of Neyshabur.