The article “Cataphracts: Armored Warriors and their Horses of War” written by Ḏḥwty was published in Ancient Origins on June 27, 2018. Kindly note that: (a) the text printed below has been edited from the original Ancient Origins article (b) none of the images and accompanying captions printed below appear in the original Ancient Origins article.

Readers further interested in Sassanian military history, may wish to consult the following sample of publications (articles and textbooks):

- Farrokh, K. (2023). Military Interactions between the Neo-Assyrian Army and Ancient Iranian Peoples: Implications for the Development of Cavalry Warfare. In D. Toichkin (ed.), History of Antique Arms – Researches 2020: Collection of Scientific Papers, Kyiv, Ukraine: Stylos, pp.140-158.

- Dwyer, B., Farrokh, K., & Khorasani, M.M. (2021). Sassanid Armor: Background, Development and Technology. SHEDET [Fayoum University, Faculty of Archaeology], Issue No 7, pp.145-183.– See News release …

- Farrokh, K., Karamian, Gh., Kubic, A., & Oshterinani, M.T. (2017). An Examination of Parthian and Sasanian Military Helmets. In “Crowns, hats, turbans and helmets: Headgear in Iranian history volume I” (K. Maksymiuk & Gh. Karamian, Eds.), Siedlce University & Tehran Azad University, pp.121-163.

- Farrokh, K., Karamian, Gh. & Kubik, A. (2016). An Examination of Parthian and Sassanian Military Helmets (2nd century BCE – 7th century CE). The Third Colloquia Baltica Iranica Conference (24-27 November 2016), Siedlice University, Poland.

- Farrokh, K., Karamian, Gh., Delfan, M., Astaraki, F. (2016). Preliminary reports of the late Parthian or early Sassanian relief at Panj-e Ali, the Parthian relief at Andika and examinations of late Parthian swords and daggers. HISTORIA I ŚWIAT, No.5, pp. 31-55.

- Farrokh, K. (2014). Soldiers of the Sassanian Empire: Rome’s unbeaten rival in the East. Military History, November Issue 50, pp.62-66, 68.

- Farrokh, K. & Khorasani, M.M. (2010), Backbone of the Empire: Sassanian Savārān. Classic Arms and Militaria, Volume XVII Issue 1, pp. 36–41.

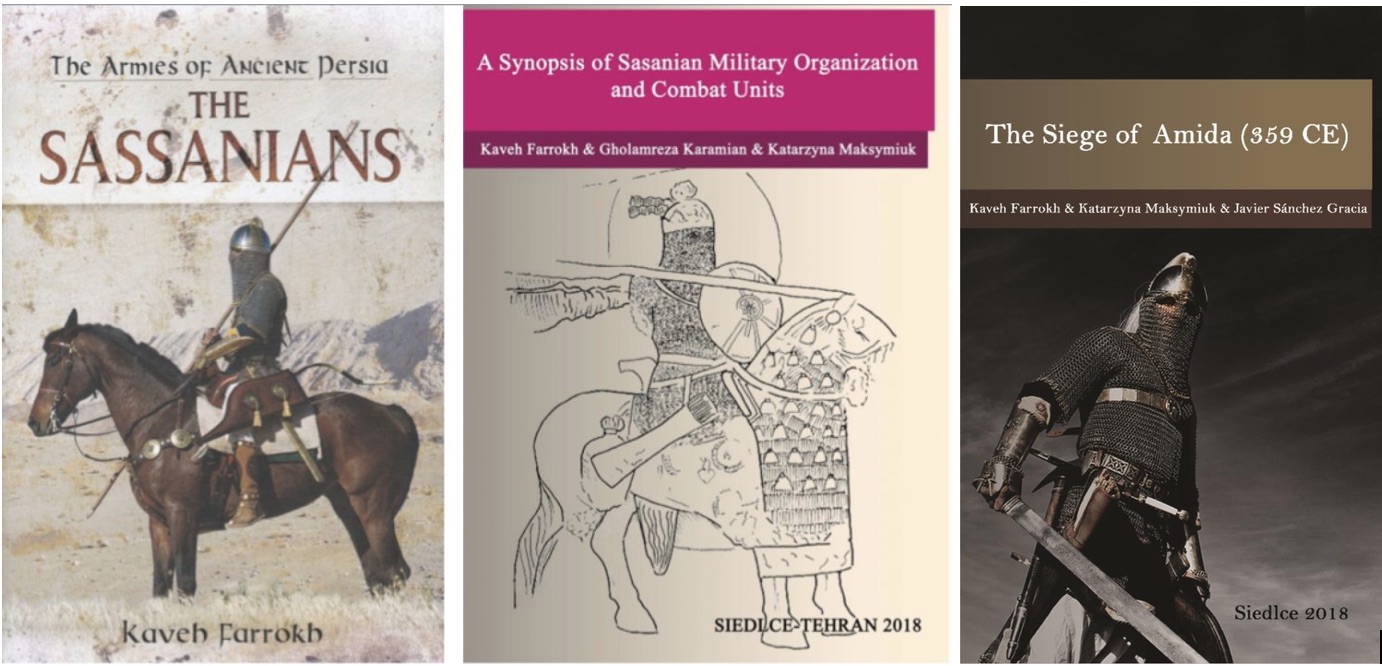

[RIGHT] Farrokh, K., Maksymiuk, K., & Sánchez-Gracia, J. (2018). The Siege of Amida (359 CE), Siedlce University: Publishing House of Siedlce University of Natural Sciences and Humanities. [CENTER] ] Farrokh, K., Karamian, Gh., & Maksymiuk, K. (2018). A Synopsis of Sassanian Military Organization and Combat Units. Teheran Azad University & Siedlce University: Publishing House of Siedlce University of Natural Sciences and Humanities. [LEFT] Farrokh, K. (2017). Armies of Persia: the Sassanians. Barnsley, England: Pen & Sword Publishing. See reviews of this book:

- Syvanne, I. (2019). Review of Kaveh Farrokh, Armies of Ancient Persia: the Sassanians. Persian Heritage, 93, p.15. See also News posting for this review …

- Gabriel, R. A. (2018). Review of Kaveh Farrokh, The Armies of Ancient Persia: The Sassanians, Military History Journal. See also News posting for this review …

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

By the 7 th and 8 th centuries B.C., the role of the chariot in battle was gradually being replaced by cavalry units in the Near East. Some were armed lightly and were used to harass the enemy from afar with missiles or to pursue routing troops. Other types of cavalry units were heavily armed, and were used as shock troops to break enemy formations. The most heavily armed cavalry unit in the ancient world was the greatly feared cataphract.

Origins of the Cataphract

The word ‘cataphract’ has its origins in the Greek language, and is said to mean ‘fully armored’ or ‘closed from all sides’. The cataphract, however, was not a Greek ‘product’, and was only adopted by the armies of the Seleucid Empire sometime during the 4th century B.C., after they went on military campaigns against the rising military power of the Iranian Parthian dynasty.

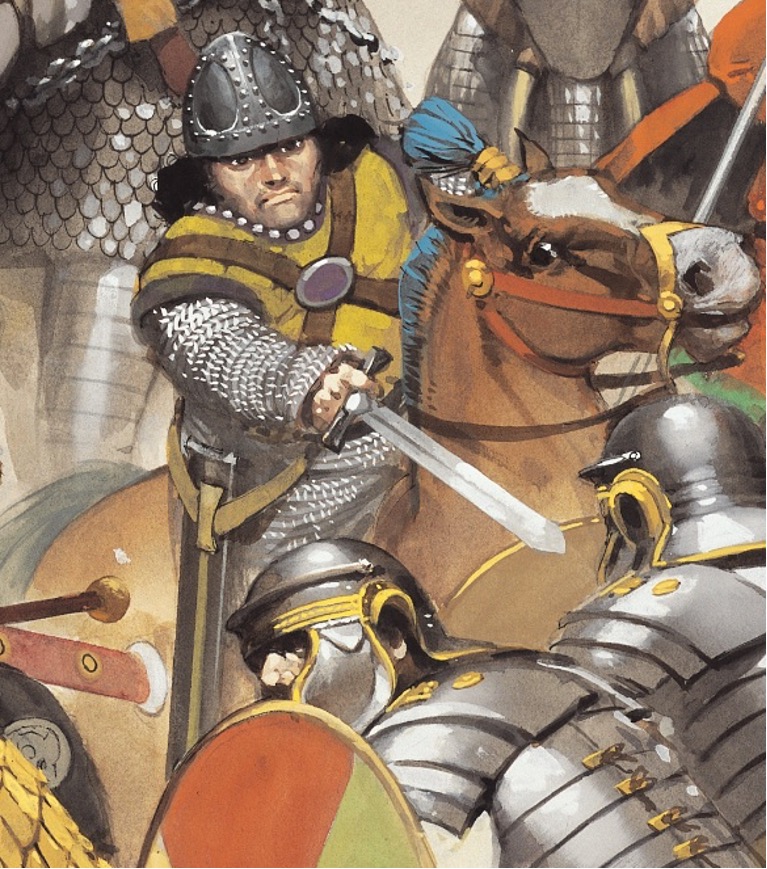

Reconstruction by Peter Wilcox and the late historical artist, Angus McBride of Parthian armored knights as they would have appeared in 54 BCE (Picture Source: Osprey Publishing).

It has been pointed out that one of the earliest known depictions of the cataphract can be found amongst the Iranian peoples in Khwarezm, a region in Central Asia near the Aral Sea. This image portrays a warrior clad in armor, armed with a lance and bow, and mounted on an armored horse. It has been estimated that these cavalrymen were used in the region as early as the 6 th century B.C. Apart from the Seleucids, various other Central Asian nations also had cataphracts in their armies.

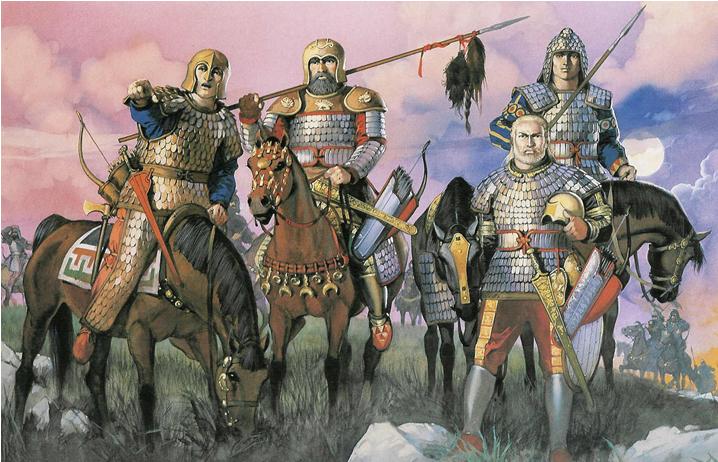

Scythians or Saka Paradraya (Iranian: Saka/Scythians beyond the sea) on the steppes of the ancient Ukraine (Painting by Angus McBride). These were the Iranian cousins of the ancient Saka, Massagetae and Khwaremians of Central Asia. Scholars are virtually unanimous that the Scythians/Saka, Massagetae, etc. were an Iranian people related to the Medes, Persians, Parthians, etc. of ancient Iran or Persia. A branch of the Scythians or Saka were to also settle in ancient northwest India to become later known as the “Sikhs” of the Punjab (Iranian: punj/panj [five], ab [water, waterway]).

The ‘Mailed Horsemen’ of Sassanian Persia

The expansion of Rome into the Near East brought them into conflict with one of these nations, the Parthians (successors of the Seleucids) and Sassanians. Thanks to the Roman historians who wrote about the conflict between Rome and Parthia, we have a certain amount of knowledge about the cataphract. Ironically, perhaps, is that one of the best descriptions of the cataphract is to be found in a novel, and not a historical work. In Heliodorus’ Aethiopica, the cataphracts, or “mailed horsemen”, are described as “the most valiant of all the Persian fighters”, and that each of them looked like “a man made of iron or a statue fashioned with hammers”.

A slide of Kaveh Farrokh’s lecture “A Synopsis of Sassanian Military Organization and Combat Units” presented in the ASMEA (Association for the Study of the Middle East and Africa) held its Tenth Annual Conference entitled “The Middle East and Africa: Assessing the Regions Ten Years On” on October 19-21, 2017 in Washington, D.C. … for more information see here …

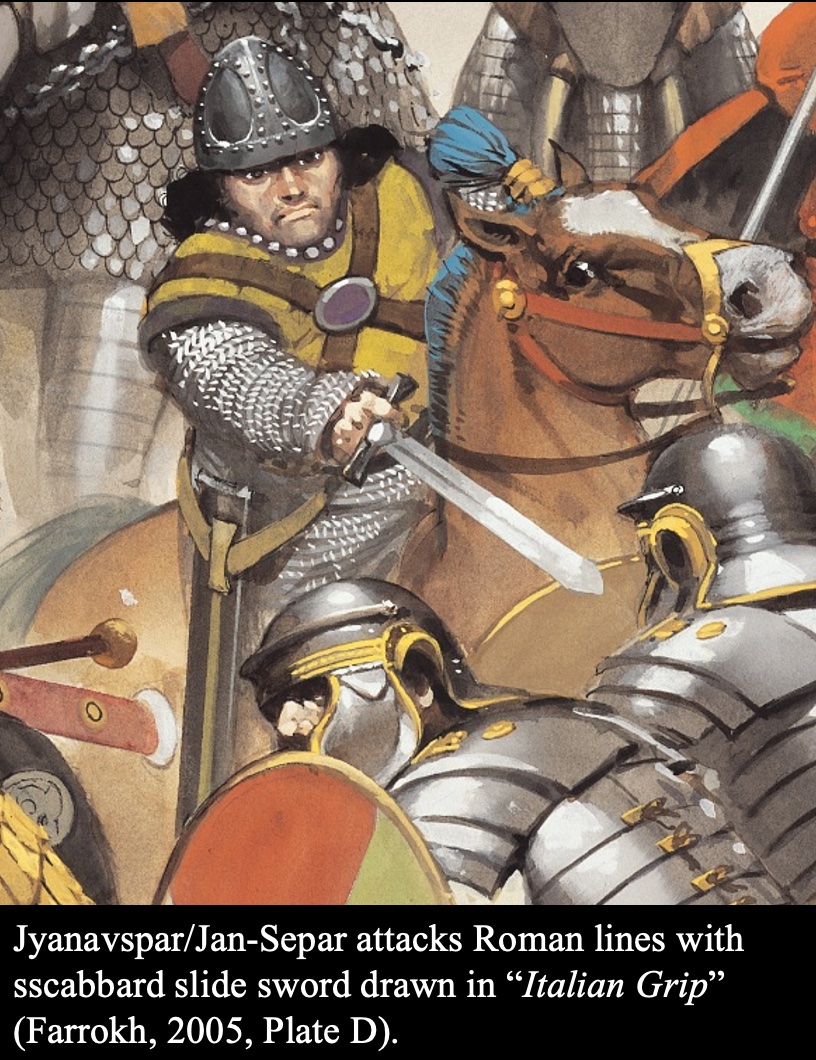

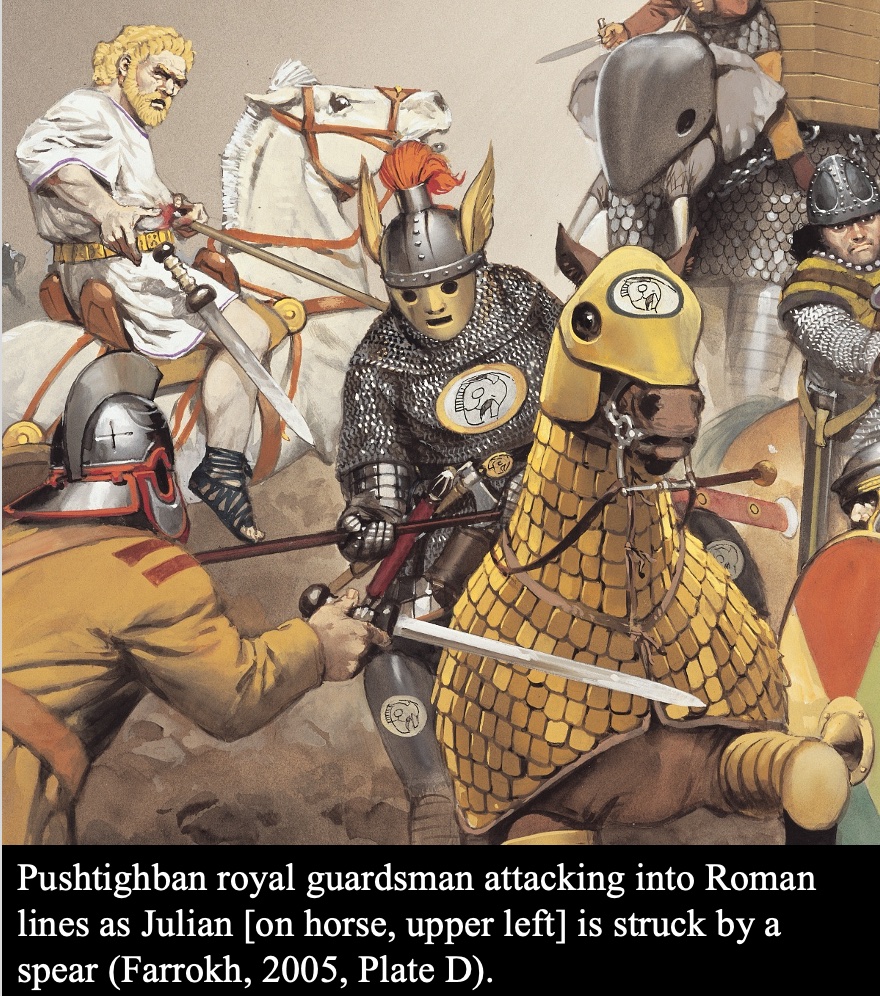

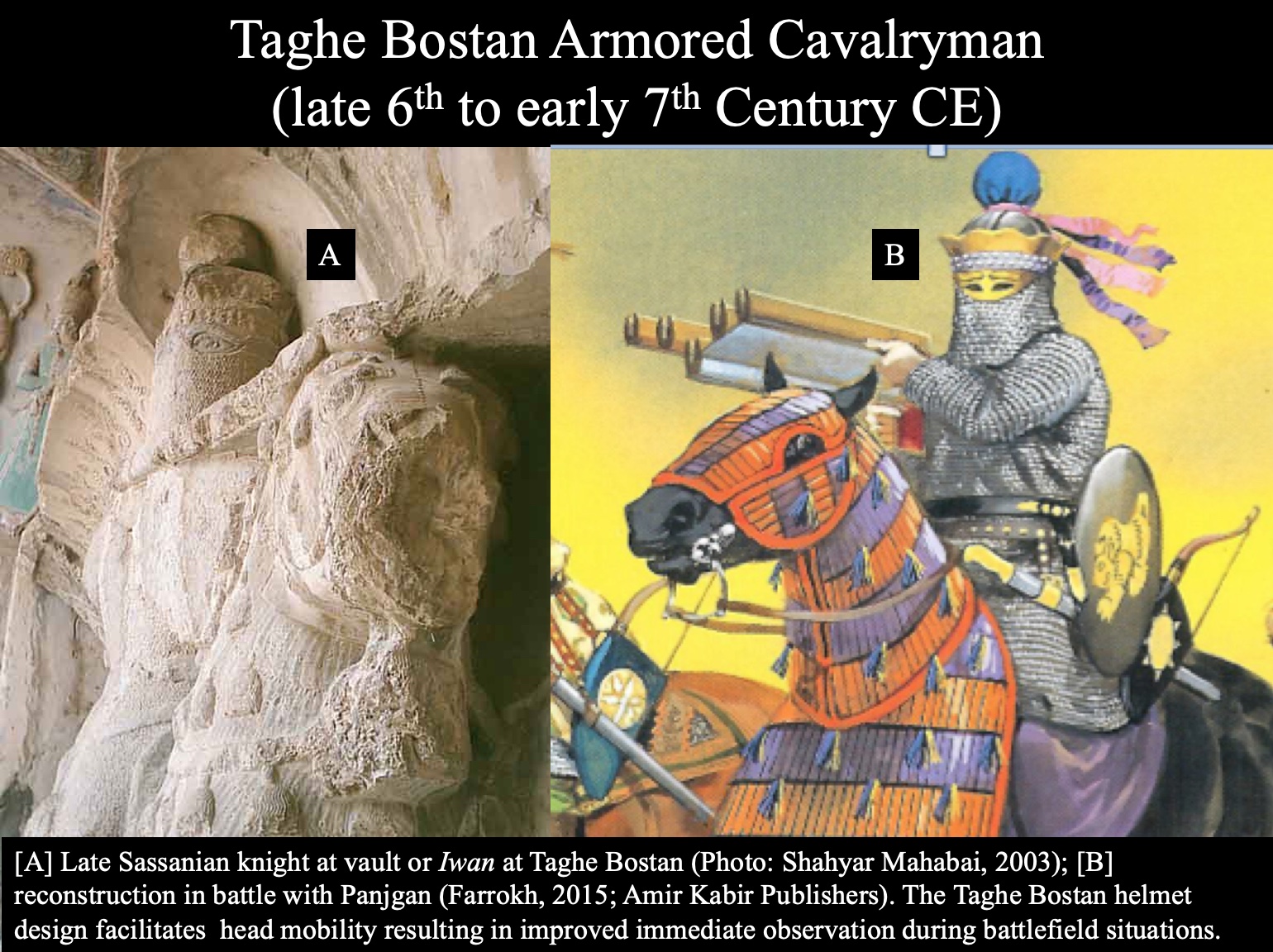

Heliodorus also provides a detailed description of the cataphract’s armor: a closed helmet covered the warrior’s head down to the shoulders, leaving only two holes for the eyes (Ammianus Marcellinus, a 4 th century Roman historian, adds that the helmets were fitted with “forms of human faces”); a coat of mail made of brass or iron scales protecting the entire body of the warrior; the horse is similarly armed. As for weapons, the warrior wields “a great staff, bigger than a spear”, and a sword.

Recreation of a Savaran knight of the Hamharzan (Ardashir Radpour) of the Sassanian Spah (Army/Military). The Hamharzan (like all other elite units such as the Pushtighban, the Shahanshah, etc.) were those warriors selected for their exceptional athleticism, courage, physical strength, martial arts abilities, alongside the ability to maintain focus and clarity under the anvil of battle. All elite units such as the Hamharzan were supplied with the highest quality weaponry.

The Cataphract Charge

Generally, the cataphract is used to charge en masse into enemy lines. Due to the sheer weight of their armor, a cataphract charge can deal a great blow to the enemy. The impact of a cataphract charge is also highlighted by the historian Tacitus, who wrote that “when they (the Sarmatians) attack the foe on horseback, hardly any line can resist them.” The irresistible force of a cataphract charge may also have a psychological effect on their enemies, as another historian, Cassius Dio, suggests. In his account of Crassus’ defeat at the Battle of Carrhae, Dio claimed that “many died from fright at the very charge of the pikemen”. The reputation of the cataphract is further enhanced by the statement (in Heliodorus and Plutarch) that their charge had enough force to impale two men in one go.

A slide of Kaveh Farrokh’s lecture “A Synopsis of Sassanian Military Organization and Combat Units” presented in the ASMEA (Association for the Study of the Middle East and Africa) held its Tenth Annual Conference entitled “The Middle East and Africa: Assessing the Regions Ten Years On” on October 19-21, 2017 in Washington, D.C. … for more information see here …

The Dangerous Life of a Cataphract

Nevertheless, the cataphract was not invincible, as his greatest strength was alsohis greatest weakness. For a start, the weight of the armor was so great that the warrior needed others to help him up onto his horse. As long as he remained on his horse, the warrior was in a safe position. If he was dismounted during battle, however, he would have been an easy target for the enemy. Although the armor afforded extra protection, it also reduced the horse’s stamina. Furthermore, overheating was also a major problem. These weaknesses were exploited by the Roman emperor Aurelian during his battle against the Palmyrenes led by Zenobia. Using his lighter cavalry, Aurelian provoked the Palmyrene cataphracts to attack. The emperor’s cavalry, however, were ordered not to engage the cataphracts, and pretended to retreat. Once the cataphracts succumbed to the heat and the weight of the armor, Aurelian’s cavalry charged and annihilated the Palmyrene cataphracts. Whilst the armor of the cataphract was able to withstand attacks from swords and arrows, they seemed to be useless against blunt weapons. During Aurelian’s battle against the Palmyrenes, he had troops from Palestine armed with clubs and staves that were used specifically “against coats of mail made of iron and brass”.

Palmyran cavalry in 272 CE confronted by Palestinian fighters of the Roman army wielding deadly clubs in the Battle of Emesa (Image Source: Posted by Kalus Petrow in Pinterest). This type of scenario was often avoided by the Sassanian cavalry as the Sassanian Spah (army) blocked opposing foot soldiers by use of horse archers, combat infantry, battle elephants, as well as foot archers.

Despite the weaknesses of the cataphract, they were still a very formidable cavalry unit. This is perhaps best seen in the fact that they were first adopted by the Seleucids, and then by the Romans. Additionally, the Sassanians and the Byzantines, the successors of Rome and Parthia respectively, also employed the cataphract in their armies.

A slide of Kaveh Farrokh’s lecture “A Synopsis of Sassanian Military Organization and Combat Units” presented in the ASMEA (Association for the Study of the Middle East and Africa) held its Tenth Annual Conference entitled “The Middle East and Africa: Assessing the Regions Ten Years On” on October 19-21, 2017 in Washington, D.C. … for more information see here …