The article “Taghe Bostan” was originally posted on July 27, 2010 in the Historical Iranian Sites and People venue. Kindly note that excepting xx pictures, none of the other images and accompanying captions printed below appear in the original posting in Historical Iranian Sites and People.

================================================================

Tagh’e Bostan is a series of large rock reliefs from the Sassanid Era located 5 kilometers from the city center of Kermanshah. It is located in the heart of the Zagros Mountains, where it has endured almost 1,700 years of wind and rain. The carvings, some of the finest and best-preserved examples of Persian sculpture under the Sassanids, include representations of the investitures of Ardeshir II (379–383) and Shapur III (383–388). Like other Sassanid symbols, Tagh’e Bostan and its relief patterns accentuate power, religious tendencies, glory, honor, the vastness of the court, game and fighting spirit, festivity, joy, and rejoicing.

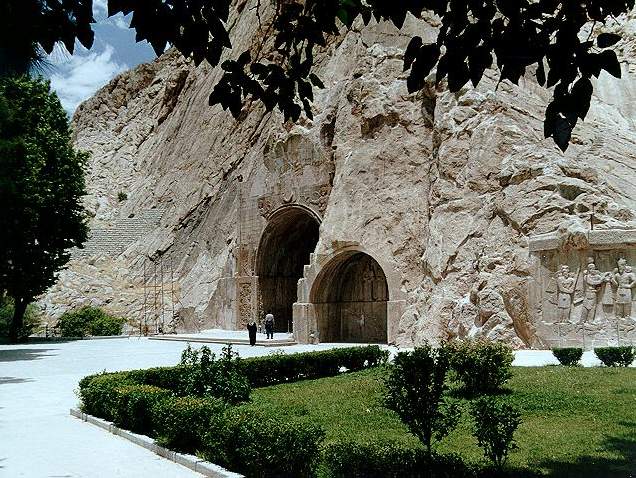

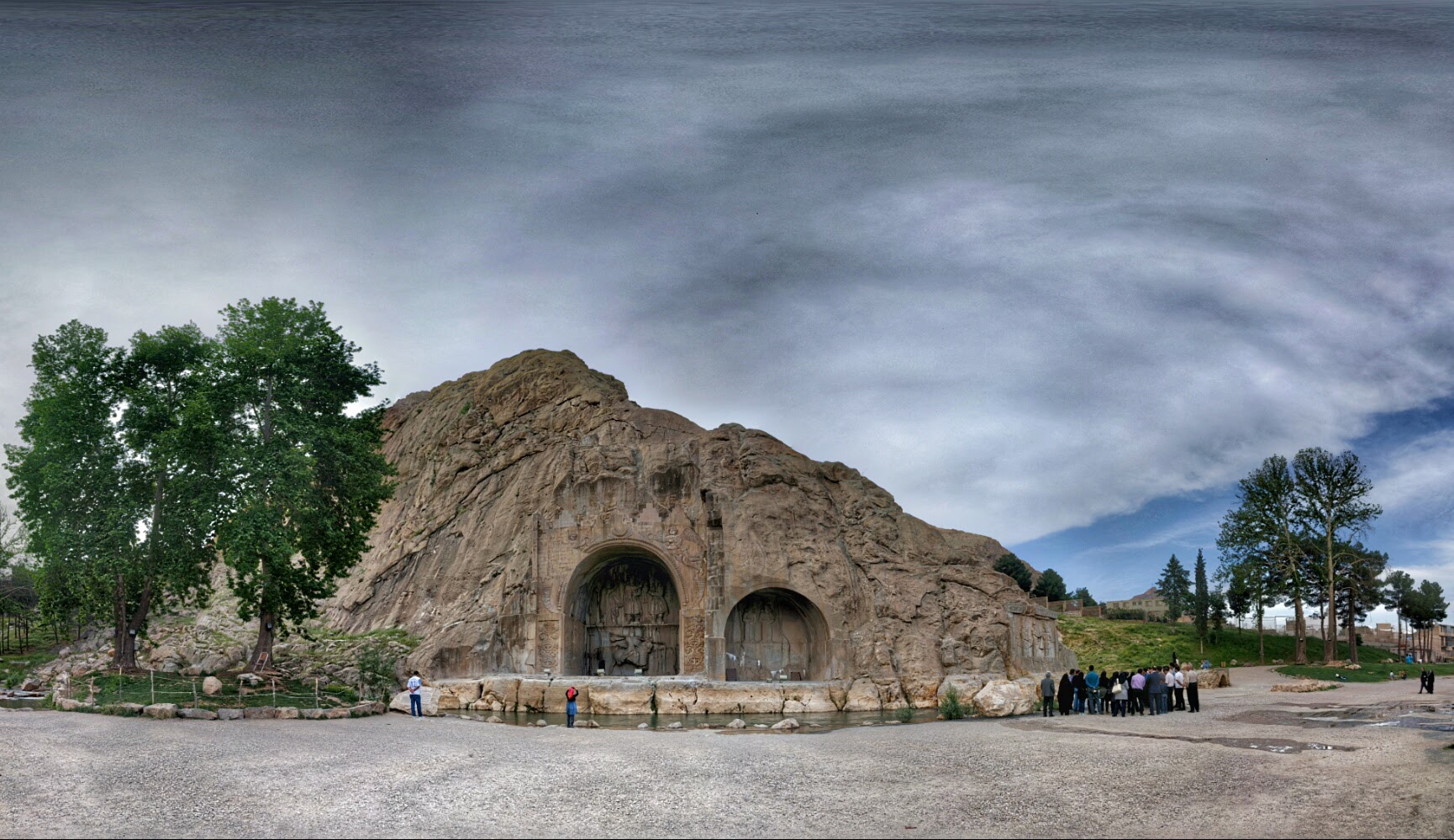

An excellent frontal view of the site of Taghe Bostan (Source: Mehdi Mizanian in Public Domain).

Sassanid Kings chose a beautiful setting for their rock reliefs along an historic Silk Road caravan route waypoint and campground. The reliefs are adjacent a sacred spring that empties into a large reflecting pool at the base of a mountain cliff. Tagh’e Bostan and its rock reliefs comprise two big and small arches. They illustrate the crowning ceremonies of Ardeshir I and his son, Shapur I, Shapur II and Khosro II. They also depict the hunting scenes of Khosro II.

The Rock-Relief panel of Mithra (left) Ardashir II (middle) and Ahura-Mazda or Shapur II (at right). Dimensions: width: 4 m and 7 cm- height: 3.9 meters. Note that Mithras appears to be engaged in some sort of “knighting” of Ardahsir II as he receives the “Farr” (Divine Glory) diadem from Ahura-Mazda (Photo Source: Shahyar Mahabadi, 2004).

The first Taq-e Bostan relief, and apparently the oldest, is a rock relief measuring 4.07 meters wide and 3.9 meters high. It includes the figures of four people with swords, helmets, and lotus, the latter being the flower cultivated extensively by Iranians. The figure standing to the right wears a jagged crown. He has turned to the middle figure and holds out a ribbon-decked royal ring. The middle figure wears a helmet. Both figures have robes that cover their bodies to the knees. Behind the middle figure, another figure stands in a halo of light around his head. Researchers have long debated the identities of the figures in this relief, although most are agreed on the identity of the fallen figure, Artabanus IV, the last Parthian King whose rule terminated in 226 AD. It is now believed that the figures represent Ardeshir I and his son Shapur I, stomping over the dead body of Artabanus IV, delighted and intoxicated with victory over their enemy. Izad, the Zoroastrian name for God, stands behind Ardeshir as a symbol of protection. This rock relief depicts the demise of the Parthian dynasty, where Artabanus’s figure has fallen under the feet of new rulers.

The smaller arch bears two Pahlavi scriptures and carvings of Shapur II, or Shapur the Great, and his son Shapur III facing each other. The figures of the two Kings have been carved in silhouette and each figure stands 2.97 meters tall. Shapur II is on the right and Shapur III is on the left with each figure’s hands placed on a long straight sword which points downwards. The right hand is holding the grip and the left rests on the sheath. Both figures wear loose trousers, necklaces, curled hair, and a pointed beard ending in a ring.

The figures of King Shapur II (right) facing his son Shapur III (left) standing at around 3 meters tall each. Note ceremonial stance of the warriors with palm of hand placed on top of sword hilt and left hand grasping hilt-handle (Photo Source: Shahyar Mahabadi, 2004).

The smaller cave within the arch’s vestibule measures 6 x 5 x 3.6 meters. It was believed to have been built during the reign of Shapur III. Some put the date of its completion at 385 AD. The Pahlavi inscriptions clearly introduces the two figures. The translation of the text of Shapur II and Shapur III respectively reads:

This is the figure of the good worshiper of Izad (God), Shapur, the King of Iran and Aniran (non-Iran), divine race from God. Son of the good worshipper of God, Hormizd, the king of Iran and Aniran, divine race, grandson of Nersi, the Shahanshah (King of Kings).

This is the figure of the good worshiper of Izad (God), Shapur, the King of Iran and Aniran, divine race from God. Son of the good worshiper of God, Shapur, the King of Iran and Aniran, from divine race.

A close-up view of a Pahlavi inscription at the Shapur II-Shapur III panel at Taghe Bostan (Photo Source: Shahyar Mahabadi, 2004). Note that the figure to the right of the photo is the partial view of Shapur III.

One of the most impressive reliefs inside the largest grotto or ivan is the gigantic equestrian figure of the Sassanid King Khosro II (591-628 CE) mounted on his favorite charger, Shabdiz. Both horse and rider are arrayed in full battle armor. The arch rests on two columns that bear delicately carved patterns showing the tree of life or the sacred tree. Above the arch and located on two opposite sides are figures of two winged angles with diadems. Around the outer layer of the arch, a conspicuous margin has been carved, jagged with flower patterns. The equestrian relief panel measures 7.45 meters across and 4.25 meters high.

The Late Sassanian knight believed to be Khosrow II and his steed Sabdiz at the great vault or Iwan at Taghe Bostan (Source: Philippe Chavin in Public Domain).

There are two hunting scenes on each side of the ivan. One scene depicts the imperial boar hunt , and in a similar spirit, the other scene shows the King stalking deer. Five elephants flush out the fleeing boars from a marshy lake for the King who stands poised with bow and arrow in hand while being serenaded by female musicians. In the next scene, another boat carries female harpists and shows that the King has killed two large boars. The next boat shows the King standing with a semicircular halo around his head and a loose bow in his hand, meaning the hunt is over. Under this picture, elephants are retrieving the game with their trunks and putting them on their backs. Each hunting relief measures approximately 6 meters wide and 4.3 meters tall.

The right panel of the Royal Hunt scene at Taghe Bostan (Photo: Shahyar Mahabadi, 2004).

Fast forwarding 1300 years in time the upper relief shows the 19th century Qajar King Fath Ali Shah holding court. The depiction was so poorly done that in an effort to mask its inferior quality in comparison to the rest of Tagh’e Bostan, color was added to it. The new addition and poor workmanship was even criticized by later Qajar King, Nasereddin Shah.

The left panel of the Royal Hunt scene at Taghe Bostan (Photo: Shahyar Mahabadi, 2004). Note that just above the left boar hunt panel can be seen the post-Islamic era relief of the Fathali Shah (1772-1834) of the Qajar Dynasty (1785-1925), which suggests that the Iranians were cognizant of the military exploits of ancient pre-Islamic Persia before the advent of Western academic studies into this domain.

The beauty and authenticity of the Sasanian site of Tagh’e Bostan has been spoilt by unwarranted additions. Throughout history Tagh’e Bostan has had a strange attraction for graffitists, would-be artists, royal inscribers and vandals and these additions have spoilt the beauty and authenticity of the original monument. One of such vandals has carved the name of the former Dutch footballer Ruud Gullit on the underside of the larger arch. Tectonic movements of the earth has caused some cracks to appear in Tagh’e Bostan, particularly on its ceiling. These cracks are getting wider due to water leaking through the stones.

Years of quarrel between cultural heritage experts and Iran’s Ministry of Transportation as well as the local authorities did not yield any results as construction of the Seyed’e Shirazi Bridge in the vicinity of Tagh’e Bostan was finally completed. Furthermore construction of a city train to reduce the heavy traffic of Kermanshah to a large extent has now become a huge concern for Iranian cultural heritage authorities and experts. Cultural heritage experts have warned that construction of a railway in the city of Kermanshah in the north-south direction will endanger Tagh’e Bostan ancient site and greatly reduce its chance of being inscribed in the list of UNESCO’s World Heritage Sites.

The Yazata or Angel at the upper right side of the archway of the Grand Iwan at Taghe Bostan (Photo courtesy of S. Amiri-Parian).