The groundbreaking research referred to in the Haaretz article was published in the July 2022 issue of the journal Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasitische Archäologie:

François Desset, Kambiz Tabibzadeh, Matthieu Kervran, Gian Pietro Basello, and Gianni Marchesi (2022). The Decipherment of Linear Elamite Writing. Zeitschrift für Assyriologie, volume 112, Number 1, pages 11–60.

NOTE By Kavehfarrokh.com: the above article has been cited as being among the “Best articles in Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies of 2022″ by the international scholarly De Gruyter … For more, see: Decipherment of 4,400-year-old Iranian Linear Writing from Elam.

Kindly note that: (a) the text printed below has been slightly edited from the original Haaretz version and (b) the images posted below have different accompanying captions from the original Haaretz report (with two images and accompanying captions not having appeared in the original Haaretz report).

===============================================================================

Ancient silver beakers from Iran may have just provided the key to a 120-year-old mystery going back 5,000 years. Created by Francois Desset a French archaeologist from Tehran University, a group of scholars has deciphered the symbols of an ancient script dubbed “Linear Elamite,” deepening scholarly understanding of the Kingdom of Elam. One of the oldest cultures in the world, it existed in Persia from the third millennium BCE until it was conquered by the Persian Empire, which it assimilated into in the sixth century BCE.

As noted by Haaretz, ancient silver beakers from Iran may hold the key to deciphering a script that has been baffling researchers for over a century. Above is an Elamite Silver cup (dated to the 3rd millennium BCE; housed in the National Museum of Iran) discovered in Marvdasht, Fars province (Source: Zereshk in Public Domain). The cup bears a Linear Elamite inscription.

The story begins in 1903, when French archaeologists excavated at ancient Susa, known in the Book of Esther as Shushan, in southwestern Iran. The excavations unearthed inscriptions in an unknown script. Later, it emerged that it was used by the Elamite culture in today’s southern Iran. Over the 20th century, researchers were only able to decipher a very small number of the Linear Elamite script’s symbols […]

The current breakthrough was reported in a scientific article published in a German-language journal of Assyriology and the archaeology of the Near East, published in Berlin and considered a key platform in the field. One of the scholars involved in the research, the Assyriologist Prof. Gianni Marchesi of the University of Bologna, Italy, explained to Haaretz how the script was deciphered:

“The Elamites used two different types of writing; the indigenous Linear Elamite script and the foreign cuneiform writing that had been imported from Mesopotamia.” Since cuneiform is well known to scholars, by reading the Elamite texts written in cuneiform, they were able to learn the names of Elamite kings and deities”

“The Elamites used two different types of writing; the indigenous Linear Elamite script and the foreign cuneiform writing that had been imported from Mesopotamia.” Since cuneiform is well known to scholars, by reading the Elamite texts written in cuneiform, they were able to learn the names of Elamite kings and deities”The next stage was to examine texts in Linear Elamite to try to identify the names of those kings and deities, explained Dr. Peter Zilberg, of the department of Archaeology and Near Eastern Studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

“How could we do it?” – Marchesi elaborated – “With a pinch of common sense, using the brain, I would say. For instance, there was a king named Puzur-Sushinak and a god named Insushinak: the two names partially overlap (their final parts coincide). This fact made it relatively easy to identify the sequences of signs of Linear Elamite corresponding to these two names; we just needed to find two sequences ending with the same group of signs. … So, from these two names we obtained the phonetic values of nine signs … which then could be used to identify other names and obtain additional phonetic values.”

“How could we do it?” – Marchesi elaborated – “With a pinch of common sense, using the brain, I would say. For instance, there was a king named Puzur-Sushinak and a god named Insushinak: the two names partially overlap (their final parts coincide). This fact made it relatively easy to identify the sequences of signs of Linear Elamite corresponding to these two names; we just needed to find two sequences ending with the same group of signs. … So, from these two names we obtained the phonetic values of nine signs … which then could be used to identify other names and obtain additional phonetic values.”

[…]

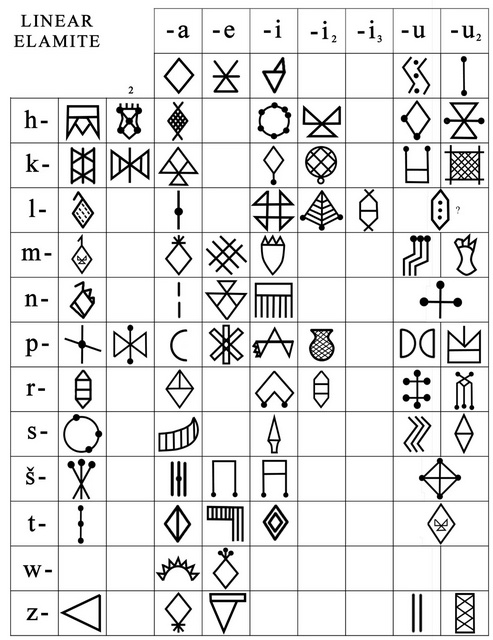

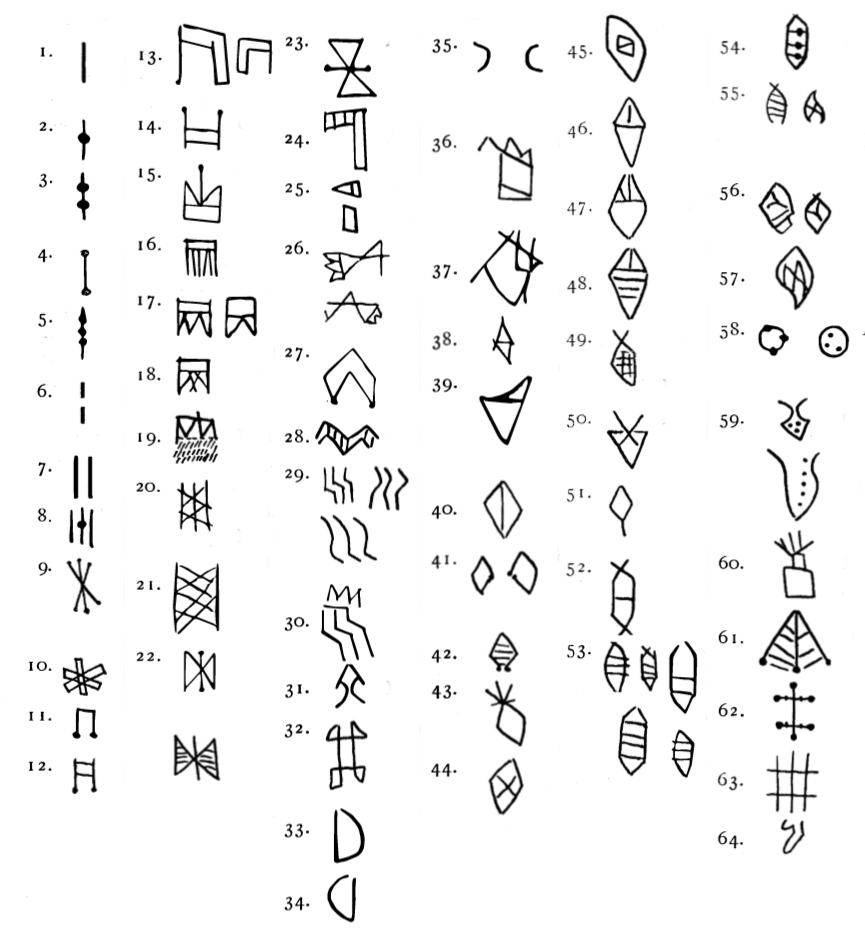

A list of known Linear Elamite characters prior to the publication in the Zeitschrift fur Assyriologie by François Desset, Kambiz Tabibzadeh, Matthieu Kervran, Gian Pietro Basello, and Gianni Marchesi (Source: Public Domain).

New inscriptions in Linear Elamite were identified by Francois Desset, a French archaeologist in Iran, on beakers that found their way to a private collection in London to which he was given access.

New inscriptions in Linear Elamite were identified by Francois Desset, a French archaeologist in Iran, on beakers that found their way to a private collection in London to which he was given access.

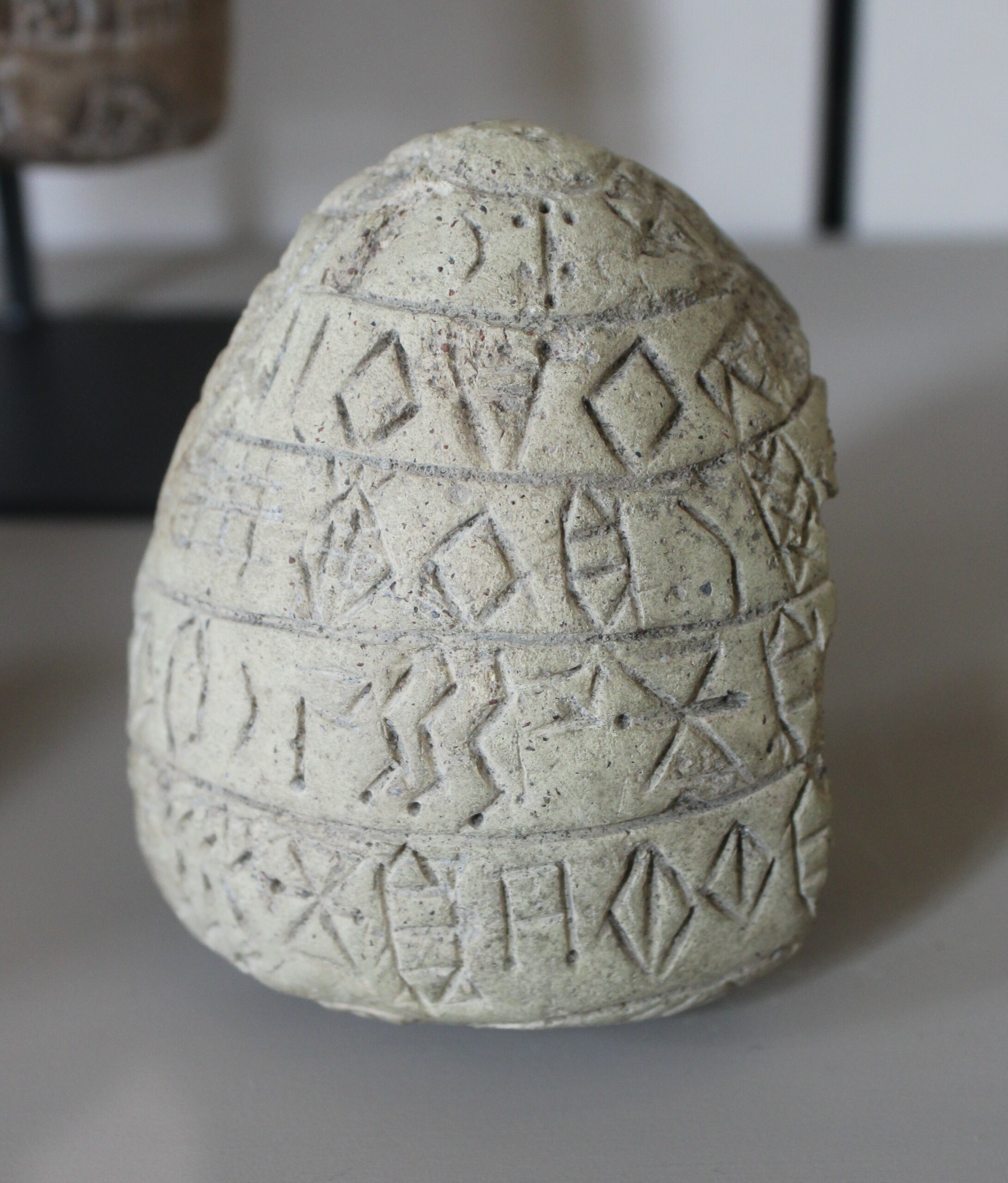

Elamite cone shaped object made of clay featuring Linear Elamite inscription discovered in the Susa region (now housed at the Louvre Museum, Sb 17830). The object dates to the reign of Elamite king Puzur-Shushinak (c. 2100 BCE) (Source: Zunkir in Public Domain).

Based on various tests, Desset posited that the vessels came from royal burial sites. He compared the texts inscribed on them to texts in Elamite written in cuneiform and on similar vessels. The assumption was that these two groups of texts would include dedications to the same rulers or have common elements (nouns, titles, and epithets) and similar expressions, the article in the German journal stated. The assumption was proven correct.

As further averred by Marchesi to Haaretz: “A second step in the decipherment consisted in trying to identify, in Linear Elamite texts, not only proper nouns but also a number of phrases, clauses, and even sentences in the Elamite language that we knew from the Elamite texts written in cuneiform, under the assumption (proven true) that the two corpora of texts (Linear Elamite and cuneiform) should share the same phraseology.”

As further averred by Marchesi to Haaretz: “A second step in the decipherment consisted in trying to identify, in Linear Elamite texts, not only proper nouns but also a number of phrases, clauses, and even sentences in the Elamite language that we knew from the Elamite texts written in cuneiform, under the assumption (proven true) that the two corpora of texts (Linear Elamite and cuneiform) should share the same phraseology.”

With painstaking work, the scholars were able to identify 72 symbols in Linear Elamite, which is believed to have between 80 and 110 symbols.

As observed by Hebrew University Assyriologist Prof. Nathan Wasserman: “Hats off to them. This was not ‘bingo’ nor the deciphering of a code in a romantic way, when suddenly everything becomes clear. As is often the case in the ancient world, it is about step after step”.

As observed by Hebrew University Assyriologist Prof. Nathan Wasserman: “Hats off to them. This was not ‘bingo’ nor the deciphering of a code in a romantic way, when suddenly everything becomes clear. As is often the case in the ancient world, it is about step after step”.

According to scholars, Linear Elamite script is an important milestone in the development of script and languages worldwide. While cuneiform and hieroglyphics were common in Mesopotamia and Egypt, symbols representing whole words (logograms) were widely used. The Elamite script is basically phonetic, that is, its symbols represent vowels and consonants. Scholars consider it the most ancient script of this kind, which is closer to the alphabet we have known since 1100 BCE thanks to the Phoenicians.

Wasserman explained that the fact that a script of this type was found:

“… at such an early stage – the end of the third millennium and beginning of the second millennium B.C.E. – is a major innovation in the world of languages altogether.” According to Wasserman, thanks to the new research “we have increased our ability to understand a very key culture in the Ancient Near East, about which we did not know much.”

“… at such an early stage – the end of the third millennium and beginning of the second millennium B.C.E. – is a major innovation in the world of languages altogether.” According to Wasserman, thanks to the new research “we have increased our ability to understand a very key culture in the Ancient Near East, about which we did not know much.”

Dr. Peter Zilberg added that deciphering Linear Elamite script is fascinating in terms of the development of script and language, because this was a local, independent script that was “simply erased by other writing systems that swept the Ancient Near East.”

Dr. Peter Zilberg added that deciphering Linear Elamite script is fascinating in terms of the development of script and language, because this was a local, independent script that was “simply erased by other writing systems that swept the Ancient Near East.”