The article “Study sheds new light on vestiges of burnt fabrics found in Persepolis” was published in the Tehran Times on July 22, 2020. The version printed further below has been edited from its original in the Tehran Times. Excepting one image, neither the video nor any of the other images and accompanying descriptions printed below, appear in the original Tehran Times report.

=================================================================================

The remains of burnt fabrics, which were found in the initial excavations of UNESCO-registered Persepolis in the southern province of Fars, were examined and studied during a 10-day project. The small and various pieces of burnt fabrics, which have been kept in the treasure trove of the UNESCO-tagged site, were considered as remnants of the site’s palaces’ curtains, but the examination of the surface layer of this collection has shown they include a variety of different fabrics and it seems they had different usages, ISNA quoted researcher Shahrzad Amin Shirazi as saying on Wednesday.

Narges Afzalipour (seated) and her colleague Shahrzad Amin Shirazi (at right) from the RCCCR (Research Center for Conservation of Cultural Relics) engaged in the examination of the 2019 discoveries of the Iranian salt mine of Douzlakh in the environs of Chehrabad (Image source: News Network Archaeology & hbz/Judith Wallerius).

The project aimed at separating and identifying different parts of fabrics and prepares them for further studies and protections measures, as noted by Shirazi. She also noted that due to their nature, fabrics are considered to be among the most vulnerable objects and for this reason, among the findings of archaeological excavations, they are much rarer and more limited than other objects, while the range of information that can be obtained by them is very wide.

Relief on the southern wall of the east stairway of the Apadana depicting Lydians who offer vases, cups and bracelets and a chariot drawn by horses (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography). Comment by Kavehfarrokh.com: The late Paul Kriwaczek (1937-2011) however had suggested that the above figures may in fact have been “… Hebrews from Babylon” (in “In Search of Zarathustra: The First prophet and the ideas that Changed the World”, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2002, description of top figure alongside page 117).

Persepolis, also known as Takht-e Jamshid, whose magnificent ruins rest at the foot of Kuh-e Rahmat (Mountain of Mercy), was the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire. It is situated 60 kilometers northeast of the city of Shiraz in Fars Province. The royal city of Persepolis , which ranks among the archaeological sites which have no equivalent, considering its unique architecture, urban planning, construction technology, and art, was burnt by Alexander the Great in 330 BC apparently as a revenge to the Persians because it seems the Persian King Xerxes had burnt the Greek City of Athens around 150 years earlier.

A video presentation entitled “Persepolis A Virtual Reconstruction” which provides a detailed reconstruction of the Persepolis city-palace (Source: MANO FONOONI of Persepolis 3D). Note that from 2 minutes and 25 minutes seconds into the above video, the building reconstructions also show the interiors in details , notably with respect to carpets, garments, upholstery, etc.

The city’s immense terrace was begun about 518 BC by Darius the Great, the Achaemenid Empire’s king. On this terrace, successive kings erected a series of architecturally stunning palatial buildings, among them the massive Apadana palace and the Throne Hall (“Hundred-Column Hall”). This 13-ha ensemble of majestic approaches, monumental stairways, throne rooms (Apadana), reception rooms, and dependencies is classified among the world’s greatest archaeological sites. The terrace is a grandiose architectural creation, with its double flight of access stairs, walls covered by sculpted friezes at various levels, contingent Assyrianesque propylaea (monumental gateway), gigantic sculpted winged bulls, and remains of large halls. By carefully engineering lighter roofs and using wooden lintels, the Achaemenid architects were able to use a minimal number of astonishingly slender columns to support open area roofs. Columns were topped with elaborate capitals; typical was the double-bull capital where, resting on double volutes, the forequarters of two kneeling bulls, placed back-to-back, extend their coupled necks and their twin heads directly under the intersections of the beams of the ceiling.

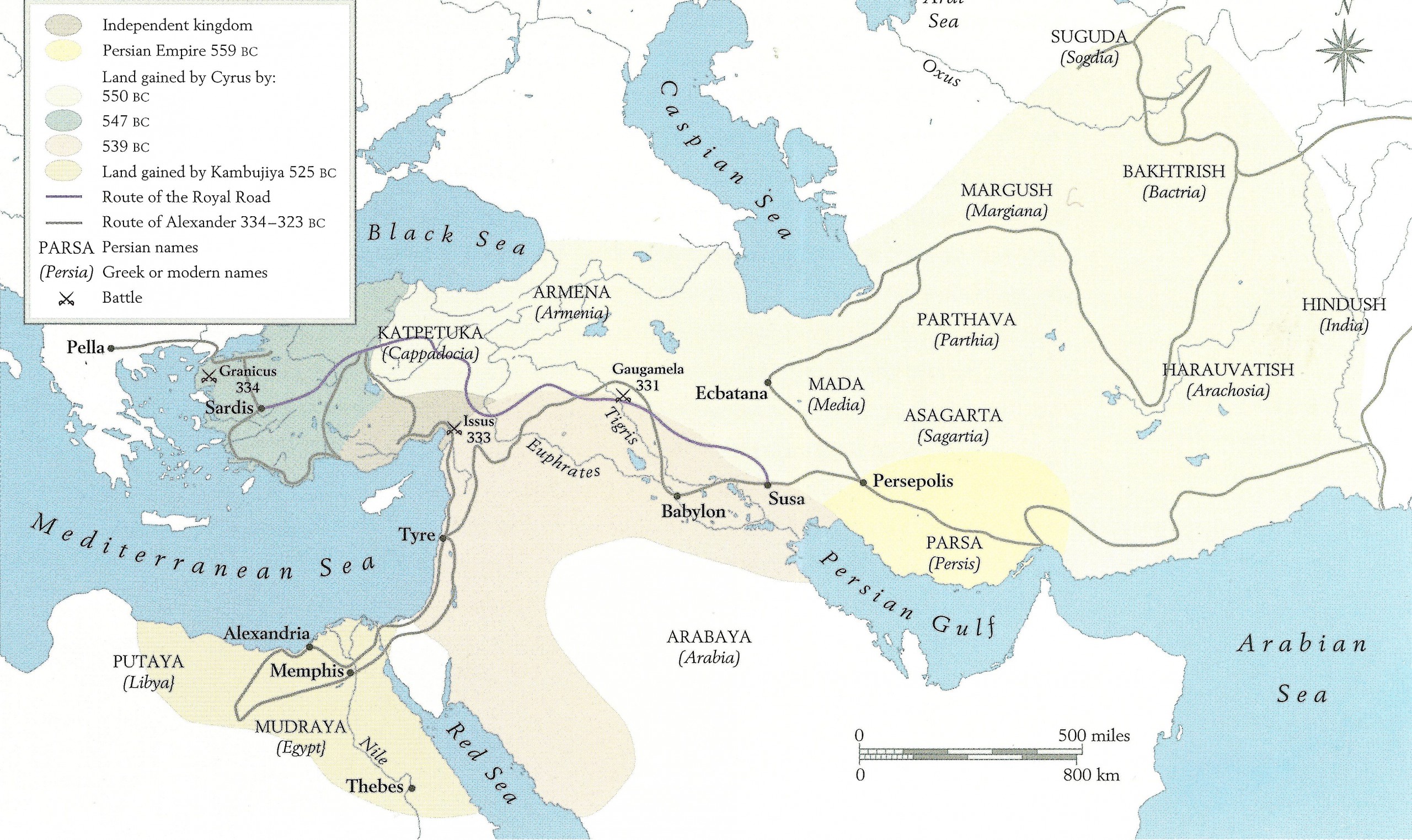

A map of the Achaemenid Empire drafted by Kaveh Farrokh on page 87 (2007) of the book Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War-Персы: Армия великих царей-سایههای صحرا-:

Persepolis was the seat of the government of the Achaemenid Empire, though it was designed primarily to be a showplace and spectacular center for the receptions and festivals of the kings and their empire. The terrace of Persepolis continues to be, as its founder Darius would have wished, the image of the Achaemenid monarchy itself, the summit where likenesses of the king reappear unceasingly, here as the conqueror of a monster, there carried on his throne by the downtrodden enemy, and where lengthy cohorts of sculpted warriors and guards, dignitaries, and tribute bearers parade endlessly.

The Persepolis Terrace in the evening (Image Source: Tehran Times).