Domenico Agostini is a senior lecturer in Ancient History at Tel Aviv University. Samuel Thrope is content manager of Maktoub Digitization project at the National Library of Israel. They are the translators of The Bundahišn: The Zoroastrian Book of Creation.

The version printed below has been slightly edited from its original version in the Jerusalem Post. In addition, the images and accompanying captions printed below do not appear in the original Jerusalem Post publication.

Readers further interested in these topics may wish to consult the following resources:

- Ken R. Vincent: Zoroaster – the First Universalist

- John Palmer: Zoroaster – Forgotten Prophet of the One God

- The Bundahishn (Bundahišn)

- Culture, Mythology & Nowruz

- The Sassanians

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

Hardly was the work of creation completed when God decided to destroy what he had made. as the Torah tells us in Genesis 6:9:

“The earth became corrupt before God, the earth was filled with lawlessness.”

And so, as the familiar story goes, God told Noah to build an ark and sent the flood to drown every man and animal who had not been granted refuge inside. When the waters receded and Noah, his family and the animals left the ark, God promised never to send such a flood again, and the rainbow was the sign of his covenant.

A 15th illustration of the building of Noah’s Ark as displayed in the Nuremberg Chronicle (1493) (Source: Public Domain).

The Noah story has inspired puzzled theologians and commentators throughout the ages. What kind of deity exterminates his own creatures on a whim? Did God not know – how could he not? – that the human beings whom he himself had created would act lawlessly? As we look back through our own bloody history, and even at the pandemic ravaging the world today, can we be certain that God has kept his promise? The Bible is not the only sacred scripture that imagines a global destruction when the world was young; other traditions also describe similar catastrophes, even floods. Among these, the ancient Iranian account is not only especially interesting to compare with the Noah story, but has a particular contemporary resonance.

Painting made in c.1911 by Léon Comerre titled “The Flood of Noah and Companions” currently housed at the Musée d’Arts de Nantes in France (Source: Public Domain).

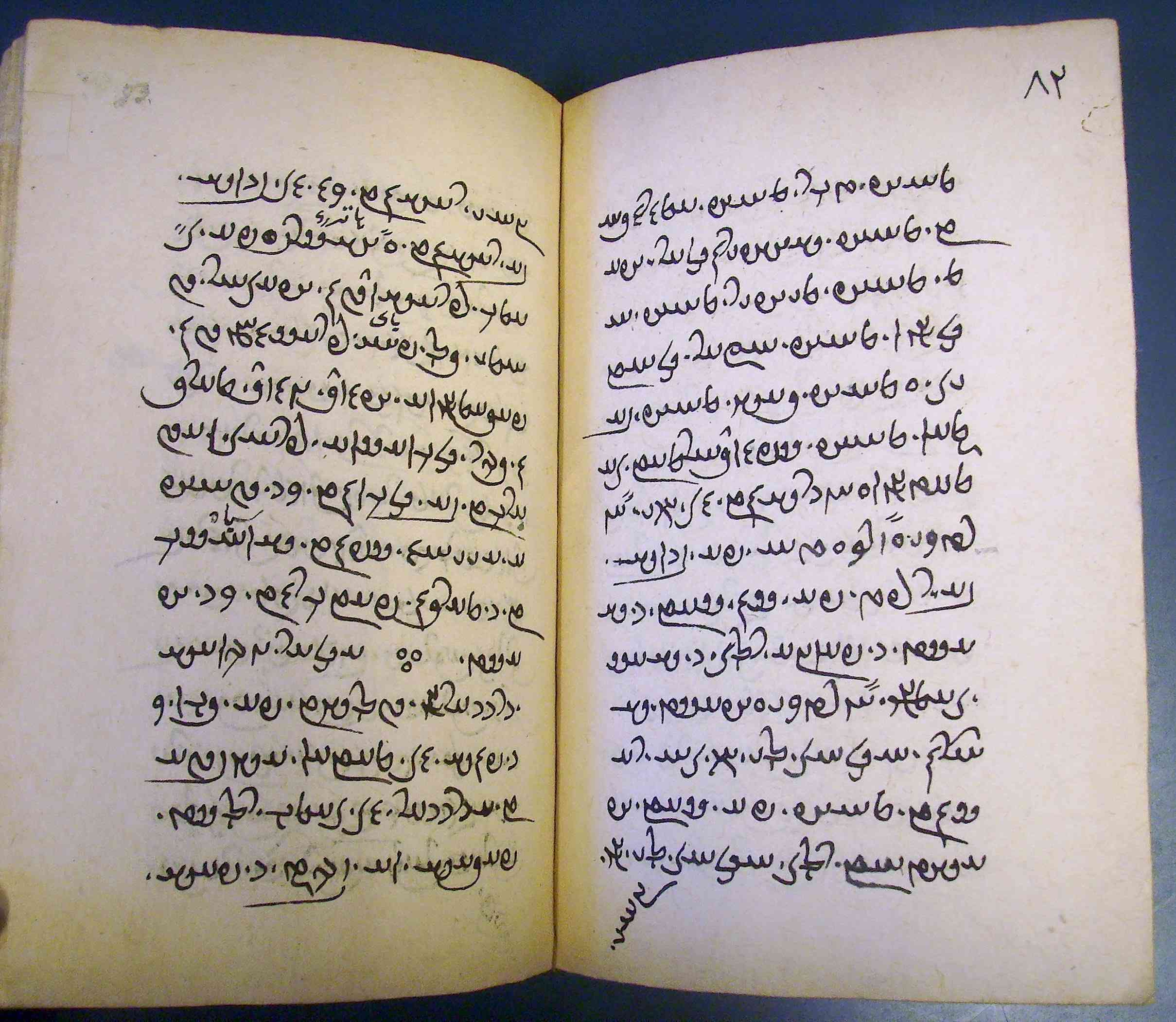

The Iranian story is told in a book known as the Bundahišn, meaning “primal creation,” one of the most important surviving records of the ancient Iranian religion, Zoroastrianism. First set down in writing sometime in the ninth century CE, the Bundahišn preserves much older traditions, stretching back thousands of years, on creation, the nature of the world and the future apocalypse. The ancient Iranian account is not only especially interesting to compare with the Noah story, but has a particular contemporary resonance.

Chapter 27 of the Bundhishn housed at the British Public Library (Source: Public Domain).

According to the Zoroastrian account, in the beginning were two primordial spirits, the good creator god Ohrmazd and the Evil Spirit, Ahriman. After Ahriman attacks Ohrmazd in the spiritual realm and is beaten back, the two agree to set a time and place for the fight that will determine who will be victorious: a period of nine thousand years in the created physical world.

Ohrmazd first created the world in perfect harmony: the earth was smooth, pleasant, and still, surrounded by the crystal vault of heaven with the sun, moon, and stars unmoving in the sky. Beside the sacred river Daiti, he created a primordial cow, plant, and human being, Gayomard.

Representation of Ohrmazd at Nagsheh Rustam where he bestows Sassanian king Ardashir I (r. 224-242 CE) with the Farr (divine glory) of kingship (Source: درفش کاویانی – Public Domain).

However, as Ohrmazd with his foresight knew, this perfect existence did not last long. Ahriman and his demon host attacked, burrowing through the sky, and mixed his evil nature with the good creation: spoiling water, ruining fire with smoke, poisoning the plant and making it wither away, killing the cow and Gayomard. As stated in the Bundahišn:

“When death came to Gayomard, the Evil Spirit first penetrated the pinky toe of his right foot, then let loose his hunger on his heart … Then he came to his shoulder, and scurried inside the top of his head. The light left Gayomard’s body, as when a blacksmith strikes a red-hot iron on an anvil and it becomes black.”

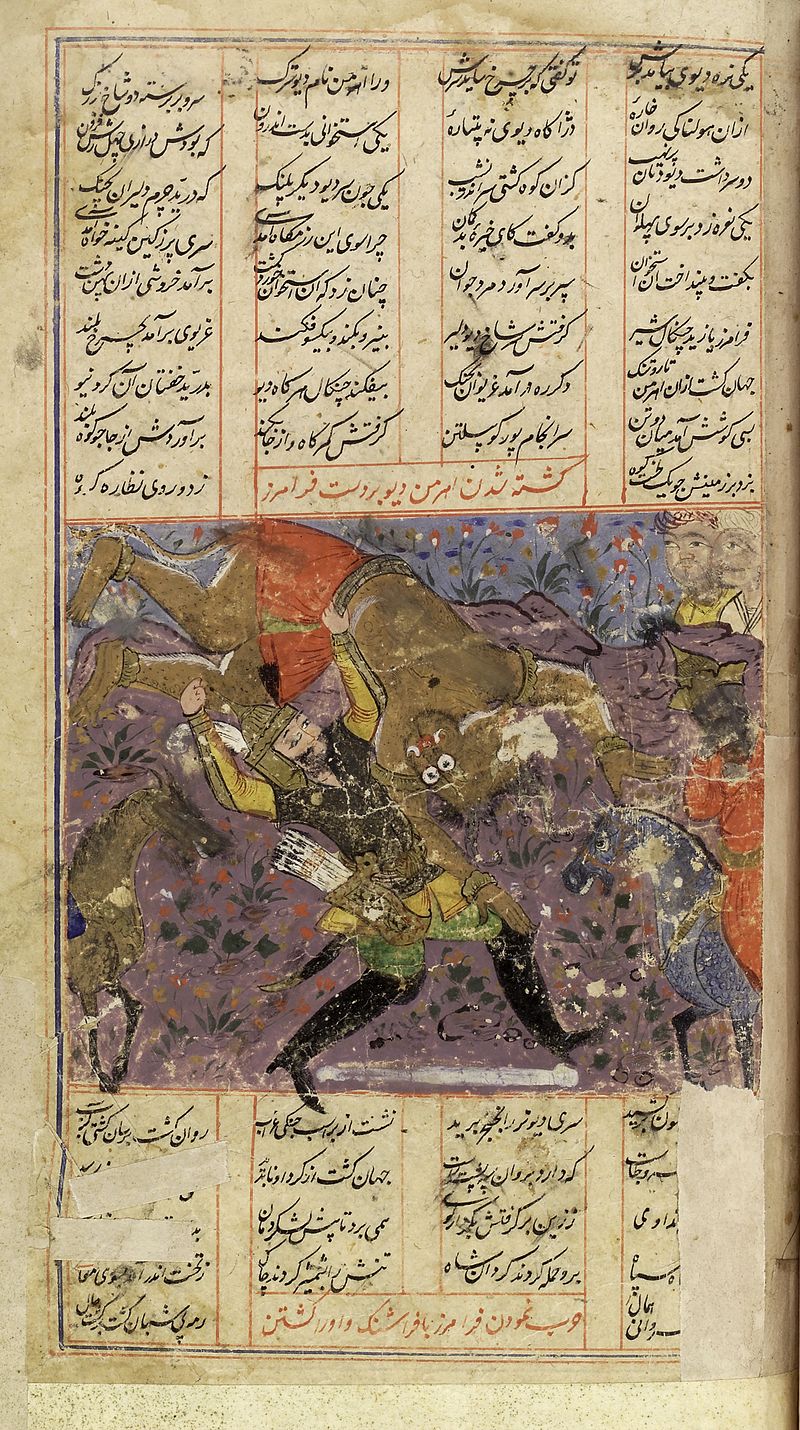

This was not the end of the story. Ohrmazd’s good creation fought back against the Evil Spirit; the world, the creatures and all of us continue the fight today. But compared with the biblical account, the Zoroastrian vision of destruction is both more logical and more motivated. The theological problems of the Noah story do not arise. For it is not the good god Ohrmazd but Ahriman, compelled by his evil nature, who destroys creation. What’s more, this destruction is an essential stage, a kind of tactical retreat, in Ohrmazd’s ultimate victory. The Bundahišn describes how – at the moment of Ahriman’s attack – the sky and the heavens begin to move, trapping the Evil Spirit and the demons; a later Zoroastrian text explicitly compares creation to a snare set to capture vermin. Unable to escape, Ahriman must remain in the world until he is finally vanquished in an apocalyptic battle at the end of time.

Illustration on a page of the Shahname depicting Faramarz slaying the evil Ahriman (Source: Public Domain).

The Bundahišn was redacted some two hundred years after the Islamic conquest of Iran that toppled the Sassanian dynasty and ended Zoroastrianism’s privileged status as an official, state-sponsored religion. Many Zoroastrians, the majority of whom did not convert to Islam until centuries after the conquest, must have feared that the world they had known was entirely upended and gone. That is the fear the Bundahišn, in this story and elsewhere, tries to assuage.

Though written long ago, the Bundahišn account is relevant for our own moment. If the reader of the Noah story is left with no small portion of anxiety about God’s whims and wills, in a time of uncertainty the Bundahišn, which divides good from evil and foresees the end in the beginning, can provide comfort. It can reassure us that the current chaos will recede and that history proceeds according to a clear and manifest plan.