The article “Bactrian fortress reveals how ancient civilizations of Central Asia lived” was originally posted on the Archaeology News Network on February 1, 2019. The original source for the Archaeology News Network is from the Akson Russian Science Communication Association. The version printed below has been edited. Excepting one photo, all other images and accompanying captions do not appear in the original reports of the Archaeology News Network and Akson Russian Science Communication Association.

=========================================================================

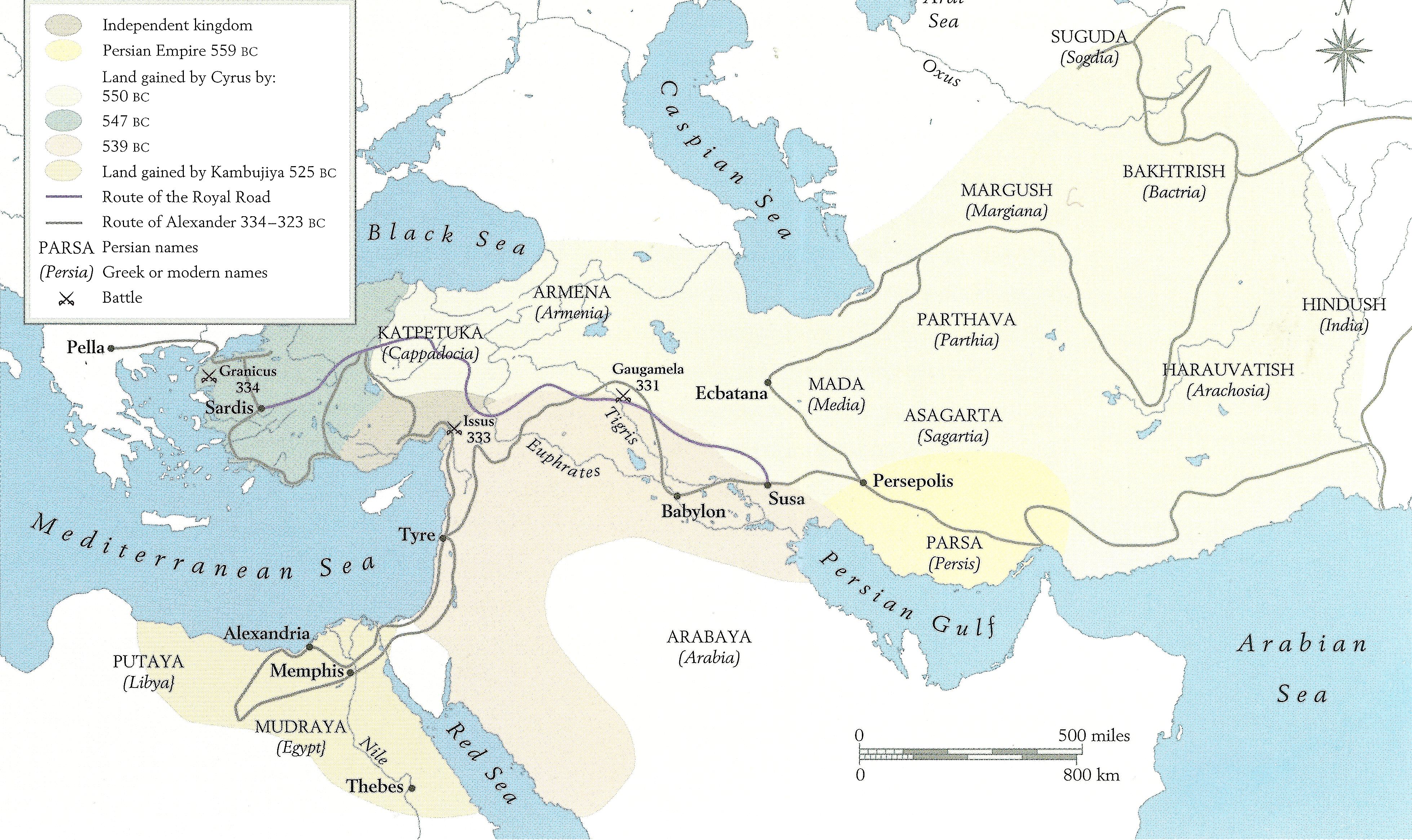

Scientists from Russia and Uzbekistan found a unified fortification system that on the northern border of ancient Bactria. This country existed in the III century BC. The fortress found blocked the border and protected the oases of Bactria from the nomads raids. During the excavations, scientists revealed the fortress citadel, drew up a detailed architectural plan and collected rich archaeological material indicating the construction, life and death of the fortress as a result of the assault. In the IV century BC, significant part of Central Asia territory belonged to Bactria, which, as a separate satrapy, was part of the Achaemenid Empire.

A map of the Achaemenid Empire drafted by Kaveh Farrokh on page 87 (2007) for the book Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War-Персы: Армия великих царей-سایههای صحرا-:– the Iranian region of Bakhtrish (Bactria) in Central Asia was a part of the Achaemenid Empire.

In 329 BC Bactria became part of the Alexander empire and after his death joined the kingdom of Seleucid: the largest Hellenistic state in the East, created by the commander Alexander Seleucius I Nicator and his son Antiochus I Soter. Gradually, the state became weakened by numerous military campaigns and the struggle for power. As a result, once flourishing Bactria ceased to exist in the II century BC when Iranian-speaking nomads from the northern territories, the Saki and Yuadzhi, broke into the country.

View of the Uzundara citadel from above (Credit: Nigora Dvurechenskaya).

Recently, Russian scientists completed excavations in this area and determined the fortress construction time: about 95-90 years of the III century BC, the time of Antiochus I reign and the very beginning of the formation of the Seleucid state. The fortress was inhabited for about 150 years.

It consisted of a diamond-shaped main quadrangle, a triangular citadel (phylacterion), surrounded by powerful double walls with an internal gallery about nine meters wide, and extension walls, which were fortified with 13 rectangular bastions-towers, three of which were also outboards. Outside the fortress there was a marketplace where local residents brought goods needed by the garrison soldiers.

The archaeologists recorded the location of each item using a total station or GPS, and then made it into a single plan tied to the terrain. As a result, the scientists managed to establish where the marketplace was, ran the road to the entrance to the fortress, and determined the place of the assault: there were more than 200 shooting arrowheads, combat darts and troops. It is curious that the proposed battlefield is located to the east of the fortress, which suggests a possible environment or the breakthrough of the enemy through a system of border fortifications.

Scythian gold artifacts from Bactria (Source: Public Domain). Note figures with Iranian tunics flanked by Iranian-type mythological winged beasts.

The warriors who defended Uzundar wore armor: in the inside-wall room of the south-western fortified wall, archaeologists discovered armor-clad plates and two right-handed iron heads from helmets. So far, scientists can not exactly determine what type of helmets these patches were — a pseudoattical or Melos group, so it is still possible that these are the same helmets that Alexander wore during Antiochus I Soter period.

As noted by Nigora Dvurechenskaya (researcher at the Department of Classical Archeology, Head of the Bactrian detachment of the Central Asian Archaeological Expedition):

“This findings are sensational: direct analogies are known from the Takhti-Sanga temple, but there they were bronze, and we found iron fragments in Uzundar. To date, there are only a few specimens and sculptures with which to compare these cheeks and determine their type. We also found fastening details, which gives important information on manufacturing technology, according to tradition, but to answer these questions requires lengthy research…”

In addition to weapons, archaeologists have collected a large number of ceramics, as well as a rich numismatic collection: today around the fortress found about 200 coins of very good preservation from the coins of Antiochus I and all the rulers of the Graeco-Bactrian kingdom from Diodot to Heliocles of very different denominations: from silver drachmas to copper mites. Such a variety proves that Bactria at the very beginning of Seleucid kingdom formation of the was part of developed monetary circulation system. Thus, the materials of Uzundara allow to study and reconstruct all spheres of life of the Seleucidian and Graeco-Bactrian fortresses.