The highly informative article and comprehensive photo essay of Persepolis further below has been written and produced by Carole Raddato who has generously allowed her work to be reproduced in Kavehfarrokh.com (kindly see her message sent on June 4, 2019:

—–Original Message—–

From: Carole Raddato <xxxxxx>

To: Dr. Kaveh Farrokh <[email protected]>

Sent: Tue, Jun 4, 2019 12:00 am

Subject: RE: Seeking Your Permission to promote your excellent article “Persepolis”Dear Dr. Kaveh Farrokh,

Thank you for your email. I would be very honoured to have my Persepolis post shared on your social media pages.

I have just returned from an archaeological trip to Iran and have so far blogged about Persepolis, Susa and Chogha Zanbil. There will be of course more sites covered on my blog. I have recently booked a trip to Alicante to see the Iran Cradle of Civilisation exhibition as nearly 200 objects from the National Museum of Iran on display there.

For your information, and also for your students, note that all my images are published under the Creative Common licence which means that they are all free to use. The best way to access them is via Flickr where they can be easily downloaded.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/carolemage/collections

Congratulations on your excellent work and your wonderful and richly illustrated Shadows in the Desert book!

Best regards,

Carole Raddato

Kindly note that the version printed below has been slightly edited from the original version.

=======================================================================================

The magnificent ruins of Persepolis, or Parsa, lie at the foot of the Kuh-i-Rahmat mountain, roughly 650 kilometres south of the capital city of Tehran, and 70 kilometres northeast of Shiraz in the Fars region of southwestern Iran. Founded around 518 BC by Darius I (the Great), the site served as the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire and was intended and designed to display the splendor and majesty of an empire that stretched from Greece to India. Sacked by Alexander in 333 BC, the site lay hidden, covered in sand until rediscovered in 1620. Persepolis was declared a UNESCO world heritage site in 1979.

Coordinates: 29° 56′ 4″ N, 52° 53′ 29″ E

Persepolis, a Greek toponym meaning “city of the Persians”, was known to the Persians as Parsa. It was a monument complex of structures built to the commands of the great Achaemenid kings between about 518 and about 450 BC. An inscription carved on the southern façade of the Terrace wall of Persepolis and written in the three official languages of the Persian Empire – Old Persian, Elamite and Babylonian – proves that Darius the Great was the founder of Persepolis. Darius states that he built this fortress upon a place where no fortress had been before and that he made it secure and adequate.

Construction began about 518 BC, as soon as work on Susa was finished. However, according to inscribed tablets found in the Treasury of Persepolis, the tremendous task was not completed until about 100 years later by Artaxerxes I (r. 465–424 BC). Darius started to erect a massive terraced platform, covering an area of 125,000 square metres of the promontory. This platform supported four groups of structures: ceremonial palaces, residential quarters, a treasury, and fortifications. All these buildings were built of locally quarried stone, and architects and craftsmen from all over Persia’s empire contributed to their construction.

A general view of Persepolis (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

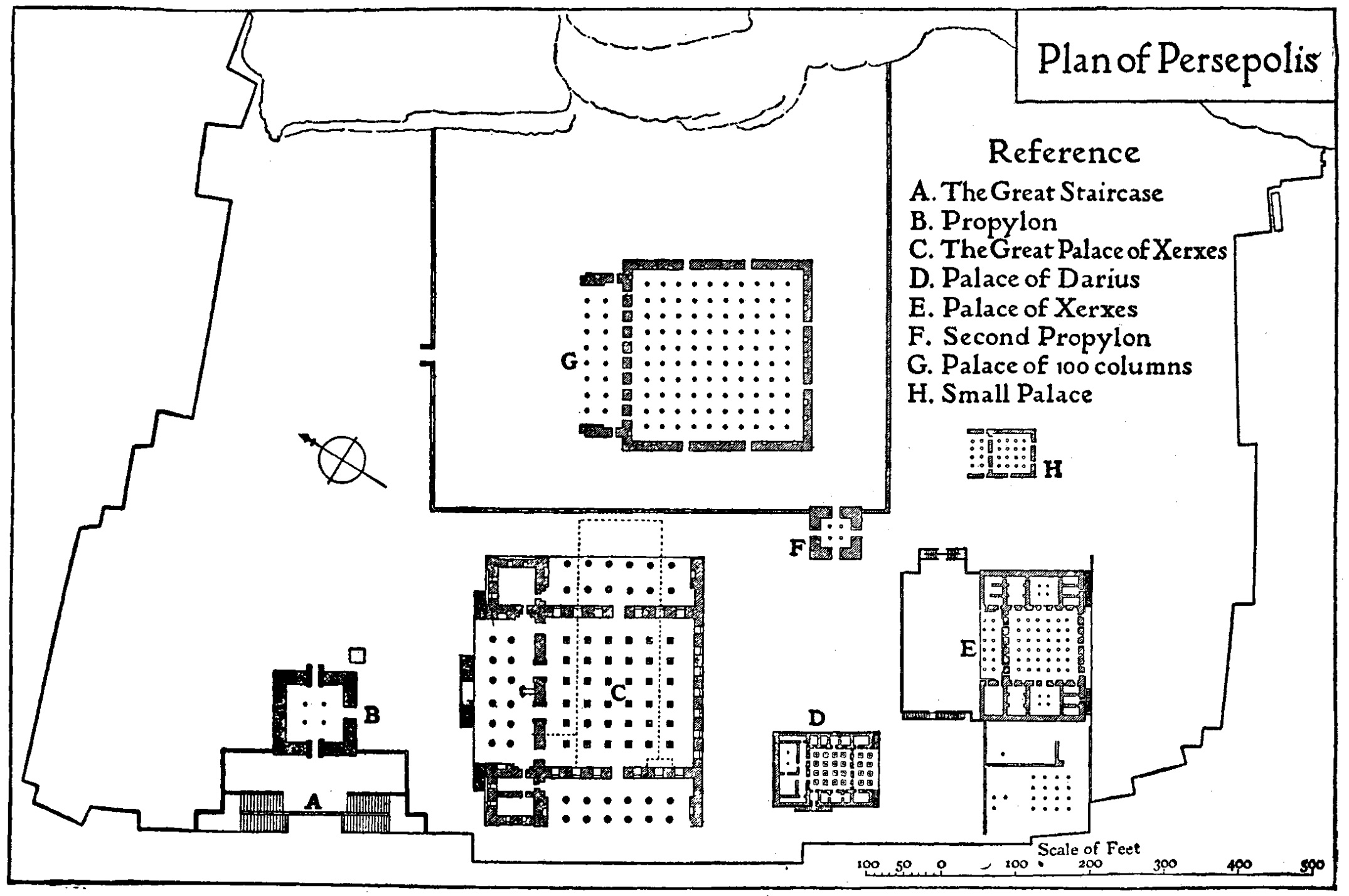

Darius planned Persepolis as a showcase of the empire, for it was here that ambassadors from all over the Persian world, from Ethiopia to Elam, would congregate each year to offer tribute to the king. The northern part of the Terrace represented the official section of the Persepolis complex, accessible to a restricted public with the Apadana, the Throne Hall, and the Gate of Xerxes (also known as the Gate of All Nations). The southern part held the Palaces of Darius and Xerxes, the Treasury, the Council Hall and the Harem. Darius constructed the platform, the monumental stairway, the Tripylon (or Council Hall), and his private palace. He also carried out the first two building periods of the Treasury and began the Apadana. Xerxes completed the Apadana, built the Gate of All Nations, his palace and his so-called Harem, and started the Throne Hall (also known as the Hall of 100 Columns). Artaxerxes I completed the Throne Hall and began work on an unfinished porch that precedes it.

Architectural Plan of Persepolis (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography – image displayed by the venue from Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, Vol. 2, Page 376).

The function of Persepolis remains somewhat unclear. Most archaeologists suggest that the site had a sacred connection to the god Mithra (Mehr) and that it was mainly used for celebrating Nowruz, the Persian New Year’s festival held at the spring equinox. More general readings see Persepolis as an important administrative and economic centre of the Persian empire.

Persepolis remained the centre of Persian power until the fall of the Persian Empire to Alexander. The Macedonian conqueror captured Persepolis in 330 BC, and some months later his troops destroyed much of the city. The great palace of Xerxes was set alight with the subsequent fire burning vast swathes of the city.

Engineering an Empire: The Persians (History Channel Broadcast posted in YouTube by Prince of Corsica).

The ruins were not excavated until the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago sponsored an archaeological expedition to Persepolis and its environs under the supervision of Professor Ernst Herzfeld from 1931 to 1934, and Erich F. Schmidt from 1934 to 1939.

Below is a portfolio of photos taken from the site of Persepolis.

Part of the monumental double staircase leading up to the terrace. Each flight has 111 steps, each 40 cm deep, 10 cm high, and nearly 7 cm wide. The stairs were carved from massive blocks of stone, but each step was shallow so that Persians in long elegant robes could ascend the 111 steps gracefully. The stairway was executed in the reign of Xerxes (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

The east side of the Gate of All Nations also known as the Gate of Xerxes which was was protected by two massive winged bulls with human heads called lamasssus (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

The Gate of All Nations was a structure which consisted of one spacious room whose roof was supported by four stone columns with bell-shaped bases. It had two large doors, probably made of wood, on the south and east of the spacious room, indicating that the gateway was designed to give access to both the Apadana and to the Throne Hall (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

The features of the four colossal figures were deliberately damaged by iconoclasts of the Islamic period to whom representation of living forms was anathema (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

The stone columns of the Gate of All Nations, they were 16 metres high and were topped with capitals in the form of a double bull (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

Double -griffin capital locally known as “Homa birds” probably from the Unfinished Gate (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

The Unfinished Gateway was began by Artaxerxes I and possibly never completed. From its southern doorway one entered a large court in front of the Throne Hall. It had a central chamber with four columns and long, narrow rooms on its eastern and western sides (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

The northern entrance to the Throne Hall. It had a portico with two rows of eight columns flanked by end walls, with figures of colossal bulls (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

The interior of the Throne Hall. The hall was 68m² and its foot was supported by ten rows of ten columns each which rose at a height of 8 metres (less than half the height of the Apadana columns) (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

The Throne Hall had eight stone doorways decorated on the south and north with reliefs of throne scenes and on the east and west with scenes depicting the king in combat with monsters (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

Throne scene relief on the southern doorway of the Hall of Hundred Columns (Throne Hall) depicting an enthroned king and attendant (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

Adjacent to the Throne Hall is the Treasury, part of which served as an armory and especially as a royal storehouse of the Achaemenian kings (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

The tremendous wealth stored in the Treasury came from the booty of conquered nations and from the annual tribute sent by the peoples of the Empire to the king on the occasion of the New Year’s feast (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

Two large stone reliefs were discovered in the Treasury that depict Darius I, seated on his throne, being approached by a high dignitary whose hand is raised to his mouth in a gesture of respectful greeting. One of the reliefs is now in the National Museum of Iran (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

The Apadana, the largest and most magnificent building of Persepolis located on the western side of the platform. It was begun by Darius and finished by Xerxes, and was used mainly for great receptions by the kings (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

Thirteen of the Apadana seventy-two columns which supported the roof still stand. On top of the columns were capitals, consisting of two heads of strong animals like bulls or lions. Between the two heads was the place where the wooden beams could rest (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

The monumental eastern stairway of the Apadana adorned with registers of relief sculpture that depicted representatives of the twenty-three subject nations of the Persian empire bringing valuable gifts as tribute to the king (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

Relief on the northern wall of the east stairway of the Apadana depicting a procession of dignitaries (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

Relief on the southern wall of the east stairway of the Apadana depicting Lydians who offer vases, cups and bracelets and a chariot drawn by horses (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography). Comment by Kavehfarrokh.com: The late Paul Kriwaczek (1937-2011) however had suggested that the above figures may in fact have been “… Hebrews from Babylon” (in “In Search of Zarathustra: The First prophet and the ideas that Changed the World”, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2002, description of top figure alongside page 117)

Relief on the southern wall of the east stairway of the Apadana depicting Syrians who offer two beautiful rams (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

Relief on the southern wall of the east stairway of the Apadana depicting an Armenian tribute bearer carrying a metal vessel with Homa (griffin) handles (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

Relief on the southern wall of the east stairway of the Apadana depicting Scythians, all armed and wearing the appropriate headgear, who offer a bracelet and folded coats and trousers (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

Relief on the southern wall of the east stairway of the Apadana (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography). Comment by Kavehfarrokh.com: This is depicting Bactrian Tribute Bearers accompanied by a two-humped Bactrian camel.

Relief on the southern wall of the east stairway of the Apadana depicting Ionian Greeks carrying what may be beehives and skeins of colored wool (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

A general view of Persepolis with the Hall of 100 Columns in the foreground and Apadana in the background (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

The ruins of the Tripylon (or Council Hall) which connected the Apadana and the Hall of Hundred Columns. The building consists of a central room and three gates that were decorated with reliefs (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

Doorjamb of the Tripylon depicting the king with attendants (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

Relief with the symbol of Ahuramazda on the on the southern end of the Tripylon (or Council Hall) (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

The Main staircase of the Tripylon (or Council Hall) in the National Museum of Iran in Tehran with reliefs depicting Persian soldiers as well as Persian and Median clergy bringing sacrifices and offerings (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

Persian soldiers depicted on the main staircase of the Tripylon (or Council Hall). National Museum of Iran (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

The palace of Xerxes (called Hadiš in Persian) was twice as large as the Palace of Darius and shows very similar decorative features on its stone door frames and windows (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography). A terrace connected the two royal mansions.

The badly ruined Palace of Xerxes who called it in one of its inscription, the Hadish, has traces of the Alexandrian fire which devastated the palace (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

The eastern staircase of the Palace of Xerxes (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

Relief of a Persian soldier (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

The western staircase of the Palace of Xerxes (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

Stone carved Faravahar (Fravahar) on the western staircase of the Palace of Xerxes (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

The Palace of Darius (also known as Tachara) (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography). The Palace was completed after his death in 486 BC by his son and successor Xerxes. Twelve columns supported the roof of the central hall from which three small stairways descend.

The palace of Darius has remained well-preserved (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography). This strongly suggests that it was one of the few structures that escaped destruction in the burning of the complex by Alexander the Great’s army.

The southern staircase of the Palace of Darius with reliefs depicting servants coming up the steps carrying animals and food in covered dishes to be served at the king’s tables (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

Relief on the southern staircase of the Palace of Darius depicting Persian soldiers (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

Relief on the southern staircase of the Palace of Darius depicting a line of attendants bearing food and drinks (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

Lion and bull relief on the southern staircase of the Palace of Darius (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

The west entrance of the Palace of Darius (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography). Measuring 1,160 square meters (12,500 square feet), it is the smallest of the palace buildings on the Terrace at Persepolis.

View of the Palace of Darius from the Apadana (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

A general view of Persepolis with the Treasury and other structures in the foreground and the palaces of Xerxes and Darius in the background (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).

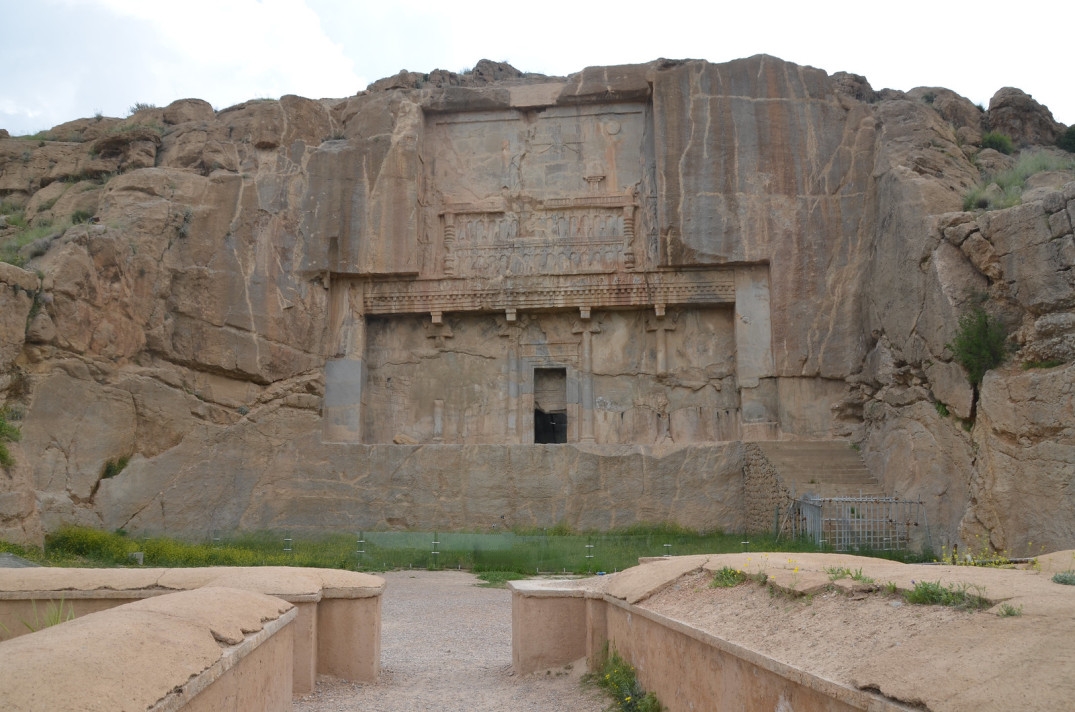

The Tomb of Artaxerxes II (r. 404-358) cut into the rock face of the Kuh-i Rahmat overlooking the Terrace (Courtesy of: Following Hadrian Photography).