Pasargadae is the site of the first capital of the Achaemenid Empire (c.550-330 BCE). Founded by Cyrus the Great (575-530 BCE). Readers are invited to consult the below article with respect to the legacy of the Cyrus:

- Farrokh, K., & Farhid, T. (1396/2018).[استوانه کوروش بزرگ و اسناد “دیگر” در بابل, مصر و ستون سنگی یادبود خانتوس] “Other” Cylinders and Records before and after Cyrus the Great: Kelar, Babylon, Egypt and Xanthus. Studies in Honor of Professor Jalal Khaleghi Motlagh (ed. F. Aslani & M. Pourtaghi), Tehran: Morvarid Publications, pp.379-394.

The term “Pasargadae” is generally believed to be the Greek phonological derivation of the Old Persian term Pathragada, which may have meant “Camp of the Persians” but this is no longer agreed upon by all specialists of ancient Iranian languages.

The construction of the Pasargadae complex drew upon artisans of not only Iranian origin (Medo-Persian), but also from Anatolia (i.e. Ionia) and Mesopotamia. These arrived at a unique architectural and civil engineering style of synthesis, one that was to herald the construction of the Persopolis city-palace. The synthesis of various artistic, architectural and engineering styles in northern, western and southern Iran however can be dated to the Elamites, the Medes as well as Luristan.

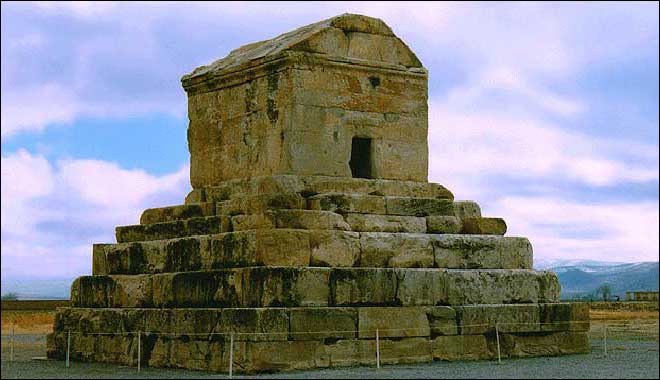

The site of Pasargadae is well known as housing the tomb of Cyrus and is also known as one of the genesis points for the Persian Gardens of old.

The Tomb of Cyrus at Pasargadae which has been listed as a World Heritage site by UNESCO.

The Tomb of Cyrus at Pasargadae which has been listed as a World Heritage site by UNESCO.

The Pasargadae tomb – a reconstruction by Stronach.

The Tomb of Cyrus: Architecture and Engineering

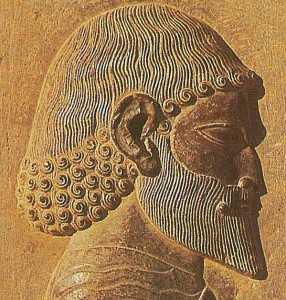

The design of Cyrus‘ tomb is fascinating as it appears to incorporate aspects of both Elamite and Mesopotamian influences. The Elamites had been fusing with the Iranian peoples in south and southwest Iran, especially the Persians (called Parsuash by the Assyrians).

Reconstruction of Pasargadae by the Persepolis-3D website – For more details on the architecture of Pasargadae, see Stronach and Gopnik: Pasargadae.

Reconstruction of Pasargadae by the Persepolis-3D website – For more details on the architecture of Pasargadae, see Stronach and Gopnik: Pasargadae. There are three sections of interest in the tomb of Cyrus. The first is an elevated podium 21.9 meters high and whose base is 13.2 x 12.2 meters. Of particular interest is the use of large blocks in the building of the podium and the tomb itself (see description of this on the History Channel program “Engineering an Empire: The Persians” below:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k6cmvM5oj3Q

The blocks at Pasargadae were cut very precisely and placed without the use of mortars. Reinforcement was provided by a unique system of clamps or staples.

Staples or clamps used to secure the blocks at Pasargadae.

Staples or clamps used to secure the blocks at Pasargadae.It is very likely that the techniques for masonry at the tomb have significant influences from the Ionians and Lydians. These influences may be explained by Cyrus’ defeat of King Croesus of Lydia (reigned 560 to 546 BC) who was King Alyattes II (619-560 BC) son and successor. Cyrus also conquered the Ionians along the western coast of Anatolia (modern western Turkey). These conquests resulted in the arrival of Ionian and Lydian artisans who bought these particular features to site at Pasargadae.

An Ionian as depicted in the city-palace complex at Persepolis

The second section is a small chamber, which appears to have some Urartian influences. Urartu located towards northwest Iran and the Caucasus (roughly where Armenia is today) had already witnessed a symbiotic relationship between its own arts and architecture and those of the Medes, although this is a domain that requires more research and excavation work. The tomb itself has the following measurements: it stands at 2.11 meters in height is also 2.11 meters wide and is 3.17 meters in length. Western researchers have noted that these dimensions resemble those found at the tomb of King Alyattes II (619-560 BC) of Lydia. While this is true, it is possible that the inspiration for this may have been derived from the underground tombs of Luristan that have similar type of roofs. Luristan has been a seminal nexus point for the genesis and synthesis of various forms of artistic, metallurgical and building techniques that were to influence the Iranian plateau and northwest Iran.

The Uratian Erebuni Fortress in modern Yerevan, Armenia.

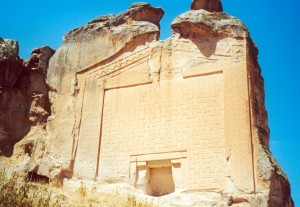

The Uratian Erebuni Fortress in modern Yerevan, Armenia.The third section of the structure is a roof and could resemble Phrygian type designs from ancient Anatolia.

A Phrygian Tomb at Midas City dated the 6th Century BC, near modern Eskishehir, Turkey.

A Phrygian Tomb at Midas City dated the 6th Century BC, near modern Eskishehir, Turkey.The arrival of Alexander

Alexander (356-323 BC) who conquered the Achaemenid Empire, held a profound sense of admiration and respect for Cyrus the Great. When Alexander arrived at the tomb of Cyrus at Pasargadae, he is described as having paid his respects at the site and also ordered the tomb repaired and its contents restored (i.e. Arrian, XXIX, 1-11; Quintus Curtius, VII, 6.20).

Alexander (356-323 BC) not only spared the Tomb of Cyrus but ordered it to be repaired and restored to its original state.

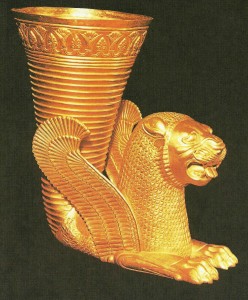

Alexander (356-323 BC) not only spared the Tomb of Cyrus but ordered it to be repaired and restored to its original state.It is believed that the items found by Alexander at the site included a carpet (possibly of the Pazyryk type), a golden coffin, bejeweled decorations, a couch with covering (or perhaps quilt of some kind) a table set with drinking goblets (possibly resembling the rhython seen in the photo below).

An Achaemenid Rhython.

This tomb continues to inspire the admiration of western researchers to this day.

The Arabian arrivals

When the Arabs conquered the Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE) and entered Iran they first planned to destroy the tomb of Cyrus at Pasargadae. Legends detail the story of how the locals dissuaded the Arabs from demolishing the site by recounting to them that it actually housed the remains of the mother of Solomon. This explains why the inscription at the site today states “Qabr e Madar e Soleiman” [The grave/tomb of Solomon’s mother].

A photograph of Pasargadae in the latter days of the Qajar Dynasty.

The tomb of Cyrus is now a UNESCO world heritage site, but has been beset by a number of controversies.

Controversies aside, one element is for certain: the legacy of Cyrus‘ humility endures to this day. An ancient inscription (now lost) is believed by many to have stated the following:

“O man, whoever thou art… I am Cyrus, Grudge me not, therefore, this little earth that covers my body.”

Further readings:

Bussagli, M. (2005). Understanding Architecture. London: I.B.Tauris.

Chahin, M. (1975). Ararat the ancient kingdom of Armenia. History Today, XXV (6), pp. 418-427.

Curtis, J. (1990). Ancient Persia. Boston: Harvard University Press.

Daniel, E.L. (2001). The History of Iran. Greenwood Press.

Ferrier , R.W.(1989) The Arts of Persia. Yale University Press

Moorey, P.R.S. (1974). Ancient Bronzes from Lursitan. London: British Museum.

Stronach, D. (1985). Pasargardae. In I., Gershevitch (Ed.), Cambridge History of Iran: Vol.2 The Median and Achaemenean Periods, Great Britain, Cambridge University Press, pp. 838-855.