NOTE: Readers reading the article “Soviet De-Iranization Policies in the Caucasus and Central Asia” may also wish to consult the following articles:

=========================================================================

A powerful proponent of de-Iranization or “Persophobia” (see discussion further below) processes was Czarist and Soviet Russia which worked hard at inculcating such sentiments in the mainly non-European colonies they conquered in the Caucasus and Central Aisa. Interestingly, these de-Iranization or Persophobic policies were often harmonious with pan-Turkim.

The Soviet Union went to great pains to extinguish the Persian cultural legacy by selectively promoting pan-Turkism. Recently two articles were posted by Tajikestanweb, namely The Axed Persian Identity Part I (see Persian translation in Shahrbaraz Blog, The Axed Persian Identity Part II and The Axed Persian Identity Part III. These essays provide a number of interesting academic and well-researched references that expose the former Soviet regime’s attempts in de-Iranianizing Central Asia, in this case Tajikestan. The article notes that:

But it should be mentioned here that Tajiks, who had no allies in the new Slavo-Turkic union, were among the main victims of the Soviet population counts and their number decreased drastically between 1917 and 1926 censuses. The chief secretary of the Tajik Committee of the Uzbek Communist Party at the time believed that the ‘biased and unfair’ 1926 census was a tool of Uzbekization. As a result, millions of Tajiks in Samarkand, Bukhara, Surkhan-Darya and other Persian-populated areas of Uzbekistan turned into Uzbeks overnight.

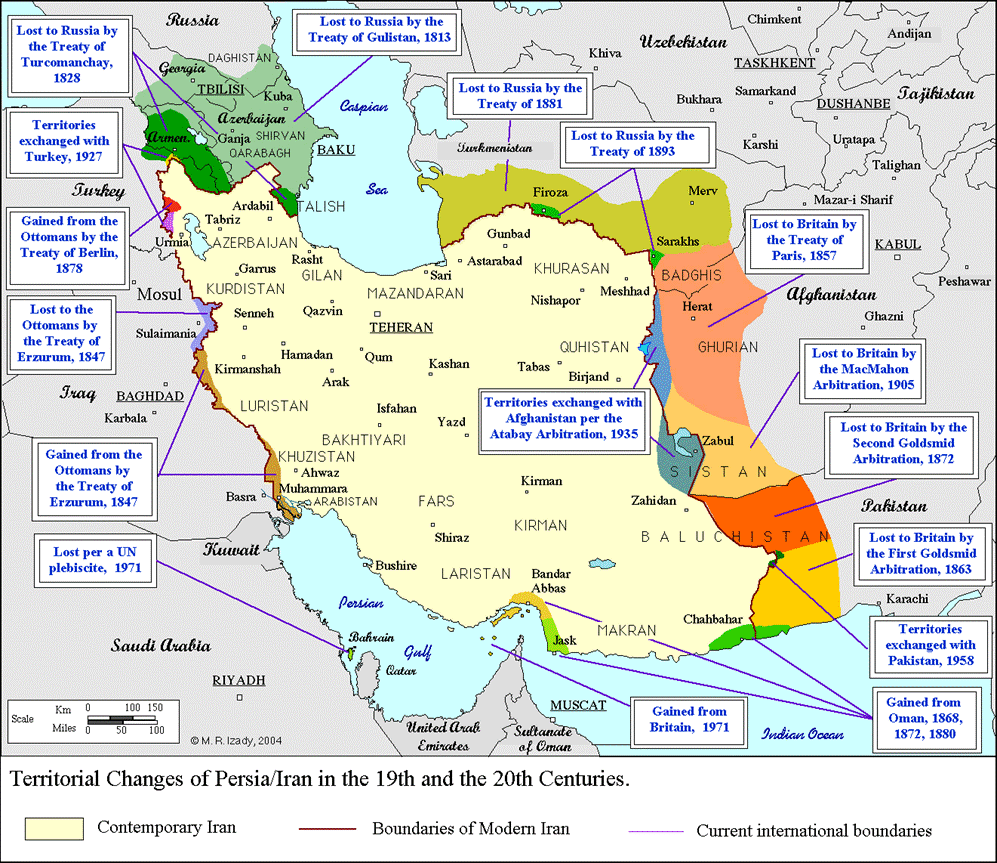

The policy of promoting pan-Turkism to destroy the Persian historical and linguistic legacy dates back to the Czarist era, in fact as far back as the 1830s, right after the conclusion of the disastrous Russo-Iranian war in which Iran was forced to cede her possessions in the Caucasus (everything above the Araxes River just above the Iranian province of Azarbaijan) to Russia.

De-Iranization in the Caucasus by Czarist Russia

Hostler reports that the Russians, despite their victory in the Caucasus, were highly apprehensive of the power and hold of the Persian language and culture over Arran (present-day Republic of Azerbaijan). According to Hostler:

“This cultural link between the newly conquered country

[modern-day Republic of Azerbaijan, historically known as Arran until May 1918] and its still strong Persian neighbor annoyed Russia who tried to destroy it by supporting local Turkish cultural developments“(1957, p.22).Zenkowski notes that despite the finalization of Russian conquests by 1826 (Treaty of Turkmenchai):

“…the Persian language remained the main language of administration in these provinces [Karabagh, Ganja, Sheki, Shirvan, Derbend, Kuba, Baku, and Talysh] until the reforms of 1840…the Persian tongue continued to be spoken in the courts until the 1870s…Persian also remained the language of the upper classes and of literature” (Zenkowsky, 1960, p.94).

The local authorities in the khanates were either Persian-speaking or of aristocracies who spoke Persian. The Shiite clergy who held considerable influence over the local courts and schools, helped maintain the influence of Iranian culture in the Caucasus.

As noted by Professor Swietochowski:

“The hold of Persian as the chief literary language in [the current Republic of ] Azerbaijan was broken, followed by the rejection of classical Azerbaijani, an artificial, heavily Iranized idiom that had long been in use along with Persian, though in a secondary position. This process of cultural change was initially supported by the Tsarist authorities, who were anxious to neutralize the still-widespread Azerbaijani identification with Persia.” (Swietochowski, 1995, p.29).

This policy was consistent with Czarist policies with respect to other recently conquered non-Russian nationalities of the empire (Swietochowski, 1995, p.29).

The above sketch clearly illustrates that de-Iranianization by Russia goes further back prior to the Soviet era.

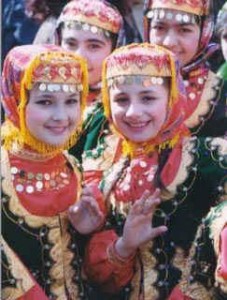

Young girls in Baku celebrating the Iranian Nowruz. Despite nearly two centuries of de-Iranization and anti-Persian cultural policies in particular by Czarist Russia, the Soviet Union and pan-Turk philosophers, Persian cultural tradtions continue to endure in the Transcaucasus.

De-Iranization in the Caucasus by the Soviet Union

Perhaps the greatest Soviet geopolitical success was in their re-naming Arran in the Transcaucasus as “Azerbaijan” when in fact no such appellation existed prior to 1918, when the pan-Turkist Musavat regime named it as much in late May of that year. The Iranian name “Azarbaijan” (versus Azerbaijan) is historically confined to the province of that name within historical Iran.

A leading proponent of Arran’s name change to “Azerbaijan” in 1918 was Mohammad Amin Rasulzadeh (1884-1955). Rasulzadeh was of Iranian stock of a noble family of Baku and wrote and spoke Persian very well; he was an active member of Iran’s Constitutional revolution in the early twentieth century (Chaqueri, Cosroe, Origins of Social Democracy in Iran, 2001, p.118, 174-181, 209-210).

Mohammad Amin Rasulzadeh (1884-1955) became the first leader of the newly created Republic of Azarbaijan

Rasulzadeh was in fact the editor of the newspaper Iran-e-Now (The New Iran). Russian influence and coercion finally forced the Iranian government to expel Rasulzadeh from Iran in 1909 (?); he was exiled to Ottoman Turkey, where the Young Turk movement had gained power.

The Young Turk movement had a profound psychological influence on Rasulzadeh; he became ensnared in the embrace of pan-Turanism. It is noteworthy that before his conversion to pan-Turaniasm, Rasulzadeh viewed himself and his native Arran (Albania) in his writings as members of:

“Our beloved homeland Iran…” (Rasulzadeh, Mohammad Amin, 1910, Tanqid-e Ferqeh-e E’tedaliyun ya Ejtema’iyun E’tedaliyun, Tehran, Farus. as cited by Atabaki, 2000, p.38).

The Soviets who took over the pan-Turkist Musavats in 1920 decided to not only retain the fraudulent name for the Transcaucasus (which was generally known as Arran), but also endeavored to perpetuate this fabrication in politicized historiography.

Rasulzadeh was to admit in 1924 to his former Iranian comrade, Sheikh Hassan Taqhizadehof Tabriz that he wished to do:

“whatever is in his power to avoid any further discontent among Iranians” (Blucher, 1984, p.37; Ayandeh, 1988, p. 57-59)

Rasulzadeh explicitly admitted to his former Iranian Azarbaijani comrade of the Constitutional movement days, Hassan Taqhizadeh , that:

Albania (present Republic of Azerbaijan) is different from Azerbaijan (the original Azerbaijan in Iran (Chaqueri, 2001, p.209)

Despite these admissions, Rasulzadeh became more and more ensnared in pan-Turanist philosophy and died a heart-broken man in Turkey in 1955. Rasulzadeh was by all accounts an honorable and honest man, however his political leanings did much to promote the de-Iranization cultural policies of both the pan-Turkists and the Soviet successors of the Czars in Russia.

The Independent Republic of Azerbaijan was dismantled and overthrown by Soviet Russian forces on April 28th, 1920, immediately after which Arran once again became a part of the Russian empire.

Interestingly, the Russians decided to retain the pan-Turanian invention for Arran, and began to refer to Arran as “The Soviet Republic of Azerbaijan”. A quick study of rare historical archives reveals a very cynically self-serving Soviet-Russian approach to the Arran affair:

“The name “Azerbaijan” for the Republic of Azerbaijan (Soviet Azerbaijan) was selected on the assumption that the stationing of such as republic would lead to that entity Iranian to become one…this is the reason why the name “Azerbaijan” was selected (for Arran)…anytime when it is necessary to select a name that refers to the territory of the Republic of Azerbaijan, we should/can select the name Arran...” (Bartold, 1963, p.217)

This was a brilliant geopolitical move, as it now allowed for Russia, like the Ottoman Turks before them, to eventually make a grab for Iranian Azerbaijan. It is very likely that Joseph (Iosef) Stalin (born Djugashvilii – his mother was Ossetian) (see photo below) was complicit in this action. Stalin deliberately and repeatedly referred to many famous Iranian literary figures (such as Nizami, Ganji, Shabestari, etc.) as:

“great national Azerbaijani literary figures”

Joseph Stalin (1878-1953)

Stalin and his writers intentionally made these statements as to omit all mention of their association and origins in Persia.

Professor Nazrin Mehdiyova, herself a historian from the modern Republic of Azerbaijan has noted that:

“…the myth [of a North versus South Azerbaijan] was invented under the Soviets for the purpose of breaking Azerbaijan’s historical links with Iran. To make this historical revisionism more acceptable, the Soviet authorities falsified documents and re-wrote history books. As a result, the myth became deeply ingrained in the population [modern-day Republic of Azerbaijan, historically known as Arran until May 1918] and was adopted by the PFA [Popular Front of Azerbaijan] as part of the rhetoric.” (Mehdiyova, 2003, p.280).

Soviet Policies in Tajikestan

Professor Mehdiyova’s observations are astute as many of the citizens of the Republic of Azerbaijan today are acutely unaware of their Iranian legacy. Nearly two centuries of Russian and pan-Turkist political and ideological manipulation have had their intended effects. But these political machinations were not confined to the Caucasus. The aforementioned Tajikestan.com article states that:

“…it should be mentioned here that Tajiks, who had no allies in the new Slavo-Turkic union, were among the main victims of the Soviet population counts and their number decreased drastically between 1917 and 1926 censuses. The chief secretary of the Tajik Committee of the Uzbek Communist Party at the time believed that the ‘biased and unfair’ 1926 census was a tool of Uzbekization. As a result, millions of Tajiks in Samarkand, Bukhara, Surkhan-Darya and other Persian-populated areas of Uzbekistan turned into Uzbeks overnight.”

Tajiks celebrate the onset of Nowruz in Dushanbe, ca[pital city of Tajikestan. The long tunics resmble the patterns seen at Tagh e Bostan in Kermanshah (western Iran). The large bugle is similar to martial instruments that may date back as far back as the Achaemenid era.

The Ottoman Empire and Russia fought long and bloody wars with each other across the centuries. However, when it came to Persian language and culture, their interests often converged. Nevertheless, the Soviets and pan-Turks were not as successful in Central Asia as they were in the Caucasus. The article continues by noting that:

“…prevailing anti-Persian sentiments of the Soviets failed to hamper Tajiks’ affinity towards their Persophone brethren on the other side of the border. Later, in 1970s, academician Babajan Ghafurov (Bobojon Ghafurov), the former First Secretary of the Communist Party of Tajikistan, contended that, in fact, Central Asia was the cradle of the medieval Persian language and culture.”

The Case of “Tajik” and “Dari”

The Tajikestan.com arricles outline how the terms “Tajik” and “Dari” were invented to distance Afghanis and Tajiks from the Iranian family. Here is a direct quote from the Tajikestan.com article:

“As recently as late 1920s the most common language in Transoxania, Afghanistan and Iran had a single official name: Persian (Farsi). Only in 1928 the Soviets renamed it to ‘Tajik’, while in both Iran and Afghanistan it was still recognized as Persian. The Pashtun King Zaher’s Afghanistan followed the Soviet path to distance the language of his country’s lingua franca from Iranian Persian by renaming it to ‘Dari’ in 1964…”

The article continues thus:

“For drawing a distinctive line between ‘Tajik’ and Persian the Soviet language-makers fabricated the history of the language as well. A myth was created about the divergence of ‘Tajik’ and Persian in the sixteenth century and all Persian authors from Rudaki to Sa’adi went under the rubric of ‘Farsi-Tajiki’.”

This is similar to what occured in former Arran the Transcaucasus, where powerful efforts from the early 19th century have been in place to diminish (if not eliminate) as much of Iran’s legacy as possible, a process which continues to proceed to the present.

Nevertheless, anti-Iranianism has not always met with success. On a personal note, I had a young female student last year who noted in a debate with another student in one of my classes that:

“Please do not say that my language is different from Persian just because the BBC [British Broadcasting Corporation] calls it Dari – Dari IS Persian! I do not know why the BBC makes it seem that Dari and Persian are different languages…”.

Persophobia

Perhaps what may explain the de-Iranianization policies is a phenomenon which the Tajikestan.com article aptly calls: Persophobia. I would qualify that with Persophobia Maximus. Here is a direct quote from the Tajikestan.com article which sums up Persophobia (Maximus):

“Andreas Kappeler and Edward Allworth, the authors of the Muslim Communities Re-emerge, believe that all those measures (to establish a ‘normative Tajik language’) were aimed at neutralizing “Pan-Iranism” among Tajik intellectuals, that is, “the consciousness of deep commonality of the cultural and linguistic heritage of the Central Asian Persian-speakers with the people of Iran and Afghanistan.”

It is notable that in a number of conferences Iranian Studies professors have noted that colleagues from Western Europe, the United States and some Arab researchers are often surprised to learn of Iran’s civilizational legacy.

Iran’s cultural and historical legacy remains mighty in both the Caucasus and Central Asia. This is already acknowledged in Persian-speaking Tajikistan, the Iranian-speaking (Ir-on and Digor) Ossetians as well as the non-Persian speaking states of the Armenia and Georgia. The acknowledgement of this process may take more time in Arran (modern Republic of Azerbaijan). This wouild be a formidable task as the re-discovery of the cultural and historical links to Iran would entail questioning nearly two centuries of pan-Turkist and Czarist-Soviet manipulated and politicized historiography. Nevertheless, the case of the Tajiks is proof that manipulated and false historical narratives can be overcome.

Further readings:

Atabaki, T. (2000), Azerbaijan: Ethnicity and the Struggle for Power in Iran. London: IB Taurus.

Ayandeh (1988), vol 4, no.s 1-2, p. 57-59.

Bartold, Soviet academic, politician and foreign office official. See Bartold, V.V., Sochineniia, Tom II, Chast I, Izdatelstvo Vostochnoi Literary, p.217, 1963

Blucher, W.V., (1984). Zeitenwende, Persian Translation: Safar-nameh-e-Blucher, Tehran, Khwarami, 1984, p.37. Chaqueri, C. (2001). Origins of Social Democracy in Iran, Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Chaqueri, C. (2001). Origins of Social Democracy in Iran, University of Seattle Press.

Hostler, C.W. (1957). Turkism and the Soviets. London: George Allen Unwin Ltd.

Kolarz., W. (1952). Russia and her Colonies. London: George Philip.

Matini, Jalal. (1989). Azerbaijan Koja Ast? [Where is Azerbaijan?]. Iranshenasi: A Journal of Iranian Studies, I (3), p.443-462.

Mehdiyova, N. (2003). Azerbaijan and its foregin policy dilemma. Asian Affiars, XXXIV (III), pp.271-285.

Swietochowski, T. (1995). Russia and Azerbaijan: A Borderland in Transition. New York: Columbia University Press.