The article below is by Professor David Stronach and Kim Codella regarding Persepolis and was first posted on-line in 1997 by the CAIS (Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies) venue by Shapour Suren-Pahlav.

Kindly note that version printed below is different in that in the Encyclopedia Iranica in that it that the embedded photo of the Apadana is that used in Kaveh Farrokh’s lectures at the University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division as well as at US and European Universities.

============================================================================

Parsa, PArseh, Takht-e Jamshid – Persepolis, site located in the southwest Iranian province of Fars, on the eastern edge of the broad plain called Marv Dasht (29°57′ N, 52°59′ E). The Achaemenid Persian ruler Darius I the Great (522-486 BCE) elected to build a new dynastic seat here to replace the prior capital, Pasargadae, some 40 km (25 mi.) to the north.

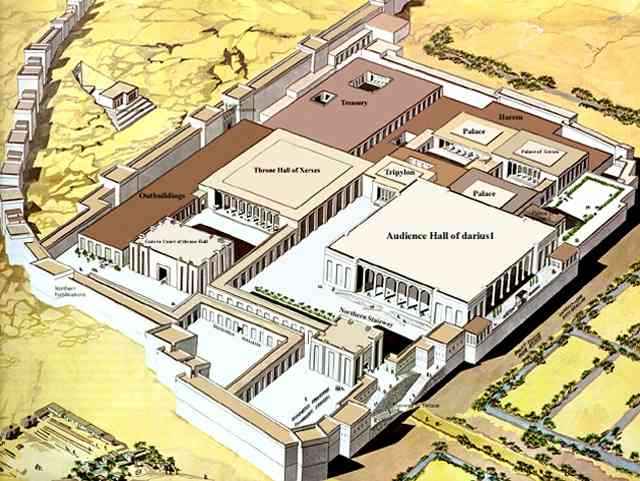

The site includes a lofty stone terrace close to 450 m long and 300 m wide (see figure below); the substantial remains of a series of relief-decorated palatial buildings; a fortified hill directly to the east; and a series of lesser representational buildings on the adjacent plain. The settlement in which the common people lived has not been identified. The sheer cliff face at Naqsh-i Rustam, 6 km (3.5 mi.) to the north, is the dramatic setting for the rock-cut tombs of Darius the Great and three others of his line.

Figure 1. The terrace view includes the Palace of Xerxes, the relatively compact Palace of Darius, the apadana (with the building’s relief decorated eastern facade hidden beneath a temporary protective covering), the Gate of All Lands, the Hall of One Hundred Columns, and the now severely denuded fabric of the multiroomed Treasury.

Four trilingual cuneiform inscriptions (in Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian) on the gate of Persepolis combine with other textual evidence (Hallock, 1969) to affirm that Darius’s extensive palace fortress was given the same name, Parsa, as the surrounding homeland of the Persians. Centuries later, when the original name and associations of the terrace had long been forgotten, certain of the carved figures in the doorway reliefs of Darius’s palace were taken to represent the mythical Jamshid, the great hunter and paramount ruler of Iran’s heroic tradition. Thus, while Biruni, an eleventh-century Iranian scientist and geographer at the court of the Ghaznavids, was not without some knowledge of Alexander’s fateful actions at the site (see below), most medieval and later Persian visitors appear to have known the terrace and its associated remains as Takht-i Jamshid, or the “throne of Jamshid.” At the same time, the site’s currently preferred designation, Persepolis, is directly drawn from the name by which it was known to the ancient Greeks (an apparent contraction of Persai polis or “the city in Persis”).

The first mention of the ruins appears in the journal of Odoric of Porderone, who passed through Fars in 1318. He refers to the site as Comerun, a corruption of a second popular designation: chehel-sotun or “forty columns,” a term signifying “many columns.” In the course of the seventeenth century, however, interest intensified: the first detailed drawings of the well-preserved site and its sculptures began to be published in Europe. Some visitors, such as Don Garcia de Silva y Figueroa, proclaimed their conviction that the ruins had to be those of Persepolis. There matters rested until the early nineteenth century, when G. F. Grotefend of Heidelberg University, working from copies of Old Persian cuneiform texts made earlier at the site, was able to distinguish the names of Darius and several of his successors. This triumph of decipherment cut through all previous speculation and pointed to the undeniable rediscovery of the Persian capital, the Persepolis of classical accounts, that Alexander had sacked and burned in 330 BCE.

Horned “devices” set up on the south wall of the platform.

Four trilingual cuneiform inscriptions (in Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian) on the gate of Persepolis combine with other textual evidence (Hallock, 1969) to affirm that Darius’s extensive palace fortress was given the same name, Parsa, as the surrounding homeland of the Persians. Centuries later, when the original name and associations of the terrace had long been forgotten, certain of the carved figures in the doorway reliefs of Darius’s palace were taken to represent the mythical Jamshid, the great hunter and paramount ruler of Iran’s heroic tradition. Thus, while Biruni, an eleventh-century Iranian scientist and geographer at the court of the Ghaznavids, was not without some knowledge of Alexander’s fateful actions at the site (see below), most medieval and later Persian visitors appear to have known the terrace and its associated remains as Takht-i Jamshid, or the “throne of Jamshid.” At the same time, the site’s currently preferred designation, Persepolis, is directly drawn from the name by which it was known to the ancient Greeks (an apparent contraction of Persai polis or “the city in Persis”).

The first mention of the ruins appears in the journal of Odoric of Porderone, who passed through Fars in 1318. He refers to the site as Comerun, a corruption of a second popular designation: chehel-sotun or “forty columns,” a term signifying “many columns.” In the course of the seventeenth century, however, interest intensified: the first detailed drawings of the well-preserved site and its sculptures began to be published in Europe. Some visitors, such as Don Garcia de Silva y Figueroa, proclaimed their conviction that the ruins had to be those of Persepolis. There matters rested until the early nineteenth century, when G. F. Grotefend of Heidelberg University, working from copies of Old Persian cuneiform texts made earlier at the site, was able to distinguish the names of Darius and several of his successors. This triumph of decipherment cut through all previous speculation and pointed to the undeniable rediscovery of the Persian capital, the Persepolis of classical accounts, that Alexander had sacked and burned in 330 BCE.

Formal excavations were slow to begin. It was only in 1924 that the Iranian government invited Ernst Herzfeld, the foremost Iranologist of the day, to prepare a detailed plan of Persepolis, together with an estimate of what it would cost to clear the site. Then, in the new circumstances that attended the abrogation (c. 1930) of France’s hitherto exclusive concession to excavate in Iran, the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago was invited to sponsor the work and Herzfeld was chosen to head the expedition. Following four campaigns, from 1931 to 1934 (during which the famed reliefs on the east side of the apadana were uncovered), the direction of the work passed to Erich F. Schmidt, who continued to excavate from 1935 to 1939. It was Schmidt, moreover, who published the results of the Oriental Institute’s all-important excavations in a comprehensive three-volume final report.

Subsequent excavations, initially conducted by Andre Godard, M. T. Mostafavi, and Ali Sami on behalf of the Iranian Archaeological Service, did much to reveal the plan of the few remaining unexamined areas of the site. The most productive advances in the last few decades may be said to have come, however, from other directions: in a new interest in the organization and chronology of the work at Persepolis (where the contributions of Carl Nylander, Michael Roaf, Margaret Root, and Ann-Britt Tilia each call for special note) and in a new level of concern for the conservation and restoration of the monuments. While work on the massive retaining wall of the partly rubble-filled terrace and on the magnificent stairway in the northwest corner of the site is likely to have begun at least as early as 515 BCE, a string of building inscriptions of Darius himself, his son Xerxes (486-465 BCE), and his grandson Artaxerxes (465-425 BCE) helps to document a subsequent, prolonged sequence of construction on the surface of the terrace from about 500 BCE down to about 440 BCE. Such inscriptions not only reflect the measured pace that was demanded by the uncompromising standards of Achaemenid construction, but they also do much to illustrate the sense of dynastic continuity that apparently inspired the completion of much of an original masterplan. It is also striking that, while there are necessarily many contrasts between the spacious plan of Pasargadae and the more condensed plan of Persepolis, both sites adhere to a distinctive Iranian preference for multiple freestanding units, rather than to the characteristic palace plan of Mesopotamia, which tended to incorporate many disparate elements under one roof (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Plan of the terrace. A = Eastern Fortification, garrison; B = Treasury; C/North = Service Quarters of Harem; C/South = Main Wing of Harem; D = Palace D; E _ Council Hall; F = Xerxes Palace; G = Palace G; H = Palace H; I = Palace of Darius I; J = Apadana; K = Gate of Xerxes; L = Terrace Stairway; M/North = Unfinished Gate; M/South = Hall of One Hundred Columns; N = Stairway to Drainage Tunnel; O = Northern Fortification; R = Southern Fortification; S = Foundation Inscription of Darius I. The double-return stairway at the northwest corner of the platform provided the only formal access to both the adjacent, supremely spacious public buildings and the more private structures located within the southern half of the terrace.

In a process that was presumably intended to underscore the exalted rank of the Persian king, all visitors to Achaemenid Persepolis were obliged to ascend the 14-meter-high double-return stairway that led to the single formal entrance to the terrace: the freestanding Gate of All Lands. This formidable square structure was marked by a single soaring hall with four stone columns and three doorways. In keeping with the Assyrian-inspired colossi that once formed part of the fabric of gate R at Pasargadae, two massive stone bulls guarded the outer doorway and two winged human-headed bulls guarded the opposite, inner doorway. Trilingual inscriptions indicate that Xerxes erected, or at least completed, this aptly named structure.

The Apadana at Parsa (Persepolis).

The hub of all else on the terrace was the imposing audience hall, or apadana (see picture below), a building that was founded by Darius and completed by Xerxes and which stood on a separate podium 2.6o m high. With a plan that can be seen to have followed that of the slightly earlier apadana of Darius at Susa, each side of this square edifice was 110 m long. Six rows of six columns (each with a square base, a fluted shaft, and a composite capital that was crowned by addorsed bull protomes) supported the cedar beams of the main hall, a vast room that stood more than 19 m high and measured 60.50 m on each side. The hall’s 5-meter-thick mud-brick walls were flanked by four corner towers and by deep recesses between the towers. To the north, east, and west these recesses took the form of tall porticoes, each marked by two rows of six stone columns set on circular, bell-shaped bases.

While the west portico provided a focal point from which the monarch could review parades on the plain below, the remaining two porticoes were each approached by monumental stairways composed of four symmetrically arranged flights of steps. Effectively carved at eye level, where all who sought an audience could not fail to observe them, the facades of these matching stairways still boast a series of reliefs that rightly remain among the most celebrated expressions of Achaemenid art (see figure 3).

When first conceived, each mirror image relief showed a procession of twenty-three tribute-bearing delegations of the empire; a central panel in which the king and the crown prince are giving audience to an official; and a third, complementary tableau that depicts (behind the royal figures) the massed files of royal guards, followed by members of the court entourage. In addition, the left and right edges of the central panel and the extreme limits of the overall composition are each flanked by the sole motif that carried any direct reference to active force: namely, the often-repeated scene of a bull being attacked by a lion (in what appears to be a representation of great power being overcome by yet greater power). Debate will of course persist, but while these and other reliefs from Persepolis were once thought to document the details of an annual new year’s festival, it now seems more probable that the above-mentioned scenes were expressly designed to illustrate Darius’s personal vision of empire: one of far-reaching, harmonious government at once secure in terms of the power and authority of the monarch and the assured condition of the royal succession.

Like the apadana, Darius’s palace stood on its own separate podium near the western edge of the terrace. An archetype for later royal residences, the building was distinguished by a single entrance portico flanked by guardrooms, a hypostyle central hall, and a series of symmetrically planned, adjoining suites. The extant stone elements of this compact structure include highly polished door, window, and niche frames (each capped by fluted, egyptianized cornices), low wall socles, and a series of elegant doorway reliefs. The latter are especially remarkable for those examples in which Darius chose to introduce a novel type of apotropaic relief: the Persian “royal hero” shown in the act of vanquishing one or another real or fabulous beast in defense (in all likelihood) of not only the actual residence of the ruler, but also the realm as a whole.

The bas-relief of Darius the Great’s Nowruz Audience, known as “Treasury Relief”.

Darius also founded, but did not himself complete, a three-doored tripylon. This monumental, enigmatic structure appears to have served as the main link between the open courts and public buildings in the northern portion of the site and the more southerly areas of the terrace that largely came to be given over to the private palaces of Darius’s successors. He also laid out the first stage of the treasury, an eventually much altered and expanded structure that served as one of the Achaemenid Empire’s richest storehouses (as well as one of the more prolific sources of metal objects, administrative tablets, seal impressions, and other notable finds recovered during Schmidt’s excavations). After 486 BCE, this latter structure came to be flanked on the west by the so-called Harem of Xerxes and, closer to the southwest corner of the terrace, by Xerxes’ palace. In architectural terms, however, the most impressive of all the later buildings at Persepolis consists of the so-called throne hall (or Hall of One Hundred Columns), which was most probably begun by Xerxes and completed by Artaxerxes. Although the square hall of this structure was not given the towering height of the main hall of the apadana, its ground area was substantially larger, with each side measuring 68.50 m.

Subsequent construction at Persepolis was mainly confined to the southeast corner of the terrace and to the creation of a series of private palaces of lesser note. A well documented exception concerns the addition of a double staircase on the south side of Darius’s palace. There an Old Persian inscription proclaims the authorship of Artaxerxes III (359-338 BCE) and an analysis of the associated reliefs shows them to be of the same late date (Roaf, 1983). Elsewhere, both Artaxerxes II (404-359 BCE) and Artaxerxes III chose to locate their sizable rock-cut tombs on the western slope of the fortified hill that overlooks the terrace. With the completion of these last two major monuments, however, a singular record of sustained architectural and artistic accomplishment came to an effective close only a handful of years before the fateful destruction of the site

[by Alexander of Macedonia].

Figure 3. Detail from the east facade of the apadana. One of the members of the Cappadocian delegation display gifts of Median-style clothing as they move towards the royal dias. The cape of the figure is fastened by an arched and ribbed fibula.

References

Balcer, Jack. “Alexander’s Burning of Persepolis.” Iranica Antiqua 13 (1978): 119-133.

Cahill, Nicholas. “The Treasury at Persepolis.” American Yournal of Archaeology 89 (1985): 373-389.

Calmeyer, Peter. “Textual Sources for the Interpretation of Achaemenian Palace Decoration.” Iran 18 (1980): 55-63.

Cameron, George G. Persepolis Treasury Tablets. Oriental Institute Publications, 45. Chicago, 1948.

Ghirshman, Roman. “Notes iraniennes VII. A propos de Persepolis.” ArtibusAsiaez0 (1957): 265-278.

Hallock, Richard T. Persepolis Fortification Tablets. Oriental Institute Publications, 112. Chicago, 1969.

Herzfeld, Ernst. Iran in the Ancient East. London, 1941.

Krefter, Friedrich. Persepolis Rekonstruktionen. Teheraner Forschungen, 3. Berlin, 1971.

Nylander, Carl. “Mason’s Marks in Persepolis: A Progress Report.” In Proceedings of the Second Annual Symposium on Archaeological Research in Iran, pp. 216-222. Tehran, 1974.

Porada, Edith. “Classic Achaemenian Architecture and Sculpture.” In The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. z, The Median and Achaemewan Periods, edited by Ilya Gershevitch, pp. 793-827. Cambridge, 1985.

Roaf, Michael. Sculptures and Sculptors at Persepolis. Iran 21 (1983).

Root, Margaret Cool. The King and Kingship in Achaemenid Art: Essays on the Creation of an Iconography of Empire. Acta Iranica, 19. Leiden, 1979.

Root, Margaret Cool. “Circles of Artistic Programming: Strategies for Studying Creative Process at Persepolis.” In Investigating Artistic Environments in the Ancient Near East, edited by Ann C. Gunter, pp. 115-139. Washington, D.C., 1990.

Sami, Ali. Persepolis. Translated by R. Norman Sharp. 2d ed. Shiraz, 1955.

Schmidt, Erich F. Persepolis, vol. I, Structures, Reliefs, Inscriptions. Oriental Institute Publications, 68. Chicago, 1953.

Schmidt, Erich F. Persepolis, Vol. z, Contents of the Treasury and Other Discoveries. Oriental Institute Publications, 69. Chicago, 1957.

Schmidt, Erich F. Persepolis, Vol. 3, The Royal Tombs and Other Monuments. Oriental Institute Publications, 70. Chicago, 1970.

Shahbazi, A. Shapur. Persepolis Illustrated. Tehran, 1976.

Stronach, David. “The Apadana. A Signature of the Line of Darius I.” In De l’Indus aux Balkans. Recueillean Deshayes, pp. 433-445. Paris, 1985.

Tilia, Ann Britt. Studies and Restorations at Persepolis and Other Sites in Fars. Istituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente, Reports and Memoirs 16, is. Rome, 1972, 1978.

Trumpelmann, Leo. Persepolis: Ein Weltwunder der Antike. Mainz, 1988.