Kindly note that: (a) the text printed below has been edited from the original ZME Science article (b) excepting one image, none of the other images appear in the original ZME Science article and (c) excepting one image, none of the captions accompanying the images below appear in the original ZME Science article.

Readers further interested in the culinary history of ancient Iran are referred to the following sources:

- Farrokh, K. (2016). An Overview of the Artistic, Architectural, Engineering and Culinary exchanges between Ancient Iran and the Greco-Roman World. AGON: Rivista Internazionale di Studi Culturali, Linguistici e Letterari, No.7, pp.64-124 (download in pdf from Academia.edu; see pages 110-116).

- Nidhi Subbaraman: Early humans in Iran were growing wheat 12,000 years ago

- Brief Notes on Spoons and Forks in Greco-Roman and Ancient Iranian Civilizations

- How Nations mix Ingredients in their Food based on Traditional Persian Medicine

- Iran’s Favorite Dish: the Chelo Kebab

- Notes on Iranian Cuisine

- A Short History of the Iranian Nān (Bread)

- World’s earliest known Wine

- The Mughal Emperor who Loved Melons

- Persian Connections to India’s Samosa

=====================================================================================

Pizza today is considered the quintessential Italian dish, but many other cultures around the world have also created pizza-like dishes. There’s some debate as to where the term “pizza” comes from. One of the prevailing theories, however, is that it comes from the Latin pitta, a type of flatbread. And, to the best of our knowledge, that is exactly how pizza started out: flatbread with extra toppings meant to give it flavor. But this idea didn’t originate in Italy. Or, more to the point, it didn’t only originate in Italy. As Genevieve Thiers writes in the History of Pizza, soldiers of the Persian King Darius I:

“… baked a kind of bread flat upon their shields and then covered it with cheese and dates” as early as the 6th century B.C. The Greeks (they used to fight the Persians a lot) seem to have later adopted and adapted this dish for their own tables.

Video titled “False Facts About Pizza Everyone Actually Believes” that traces the historical origins of the Pizza dish (Source: Mashed).

It was pretty common for ancient Greeks to mix olive oil, cheese, and various herbs into their bread — again, all in the name of flavor. But it seems that contact with Persian soldiers added a twist or two to the tradition, according to Thiers, and Greece started baking “round, flat” bread with a variety of toppings such as meats, fruits, and vegetables.

Persian-style “Pizza” from the eateries of Tehran (Picture Source: iFood.TV).

One interesting bit of evidence of this culinary development comes from the Aeneid, an epic poem written around 30 or 20 B.C. In the work, Aeneas and his men (who were running away from Greek-obliterated Troy) receive a prophecy/curse from Celaeno (queen of the harpies). Caleano told him that his group will “have reached [their] promised land” when they “arrive at a place so tired and hungry that [they] eat [their] tables”. When the party came ashore mainland Italy they gathered some “fruits of the field” and placed them on top of the only food they had left — stale round loaves of bread.

Italian cuisine

The ‘pizzas’ we’ve talked about up to now are far from unique. Cultures around the world have developed their own brand of goodie-laden bread. Flatbreads, naan, and plakountas are all early preparations that could be considered cousins to the modern pizza, and they sprung up from ancient Greece to India, from Persia to Egypt. However, it would be kind of a stretch to call them pizza; they’re certainly not what you’d expect to see inside a pizza box today. One Greek settlement would become the forefront of pizza as we know it: Naples. The city was founded by Greek colonists in the shadow of Vesuvius around 600 B.C.

Ancient Roman mosaic depicting the baking of a possible early precursor to Italy’s modern-day Pizza (Source: Magdalenes Pizza).

Writing in Pizza: A Global History, Carol Helstosky explains that by the 1700s and early 1800s, Naples was a thriving waterfront city — and, technically at least, an independent kingdom.

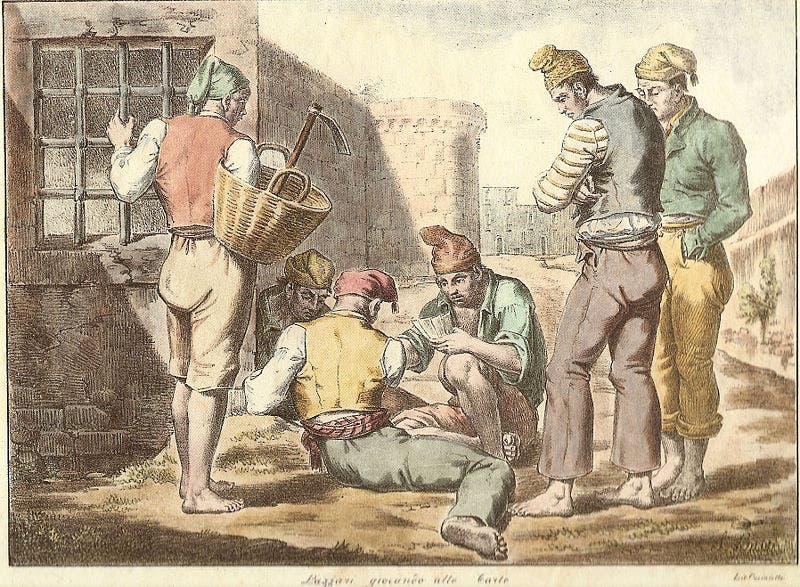

The city was famous for its many Lazzaroni, or working poor. They needed inexpensive food that could be consumed quickly, for the lazzaroni had neither the time nor the money to invest in their meals. Many street vendors and other informal “restaurants” catered to their need, primarily offering flatbreads with various toppings (as per the area’s Greek heritage). By this time, Naples’ flatbreads featured all the hallmarks of today’s pizzas: tomatoes (which were brought over from the Americas), cheese, oil, anchovies, and garlic.

Still, the dish wasn’t enjoying widespread appeal or recognition at this time. Pizza was considered a poor man’s dish, partially due to the Lazzaroni, partly due to the fact that tomatoes were considered poisonous at the time. Wealthy people, you see, used to dine from pewter (a lead alloy) plates at the time. Tomatoes, being somewhat acidic, would leach lead out of the plates into food — which would eventually kill these wealthy people. The tomatoes were blamed, and that made them cheap. The lazzaroni were poor and hungry, so the tomato was right up their alley. Luckily for the lazzaroni, pewter plates were expensive, so they weren’t poisoned. Helstosky notes:

“Judgmental Italian authors often called [the Lazzaroni’s] eating habits ‘disgusting” .

Pizza got its big break around 1889. After the kingdom of Italy unified in 1861, King Umberto I and Queen Margherita visited Naples, Thiers writes. It’s not exactly known how but they ended up being served ‘pies’ made by Raffaele Esposito, often hailed as the father of modern pizza. Legend has it that the royal pair was bored with the French cuisine they were being offered, although Europeans love bad-mouthing their neighbors and especially their neighbors’ foods, so that may not be completely factual. As explained by Thiers:

“He first experimented with adding only cheese to bread, then added sauce underneath it and let the dough take the shape of a large round pie”.

Esposito is said to have made three of his pies/pizzas. The story goes that the one the Queen favored most showcased the three colors on Italy’s flag — green basil, white mozzarella, and red tomatoes. Whether this was a coincidence or by design, we’ll never know. But you can pick the story you like most. Esposito named his pizza “Margherita” in honor of the Queen, although today it’s more commonly referred to as ‘cheese pizza’.

A modern-day Italian Margherita pizza (Source: stu_spivack in Public Domain). One of the legends pertaining to this dish is that it features the three colors of the Italian flag: green (green basil), white (cheese) and red (red tomato). The colors of Italy’s national flag are shared with the Iranian flag.

From there, pizza has only reached greater heights. It established itself as an iconic Italian dish, first in Italy and later within Europe. America’s love of pizza began with Italian immigrants and was later propelled by soldiers who fought — and ate — in Italy during the Second World War.

Today, it’s a staple in both fast-food and fancy restaurants, can be bought frozen, or can be prepared at home (it’s quite good fun with the right mates). I think it’s fair to say that although Persia’s soldiers couldn’t conquer the world, their food certainly did.

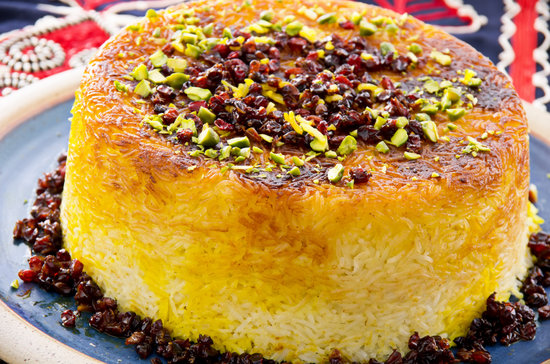

The Tahdig delicacy crust shaped around the rice in the form of a cake (Picture Source: Brad Budge). There are in fact large varieties of the Tahdig.