The article below is by H. E. Wulff, originally published in the April 1968 issue of the Scientific American (pages 94 – 105) to be republished more recently in CAIS (Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies). Note that Iranian Qanat aqueducts are now registered with UNESCO whose website provides the following description:

“Throughout the arid regions of Iran, agricultural and permanent settlements are supported by the ancient qanat system of tapping alluvial aquifers at the heads of valleys and conducting the water along underground tunnels by gravity, often over many kilometres. The eleven qanats representing this system include rest areas for workers, water reservoirs and watermills. The traditional communal management system still in place allows equitable and sustainable water sharing and distribution. The qanats provide exceptional testimony to cultural traditions and civilizations in desert areas with an arid climate.”

Readers further interested in these topics may wish to consult the following resources:

- UNESCO: Shushtar Historical Hydraulic System

- Parthian-era Qanat Discovered in Southern Iran

- Learning, Science, Knowledge, Technology & Medicine

===================================================

A traveler flying over Iran can see plainly that the country has an arid climate. The Iranian plateau is largely desert. Most of Iran (excepting areas in the northwestern provinces and along the southern shores of the Caspian Sea) receives only six to 10 inches of rainfall a year. Other regions of the world with so little rainfall (for example the dry heart of Australia) are barren of attempts at agriculture. Yet Iran is a farming country that not only grows its own food but also manages to produce crops for export, such as cotton, dried fruits, oilseeds and so on. It has achieved this remarkable accomplishment by developing an ingenious system for tapping underground water. The system, called qanat (from a Semitic word meaning “to dig”), was invented in Iran thousands of years ago, and it is so simple and effective that it was adopted in many other and regions of the Middle East and around the Mediterranean.

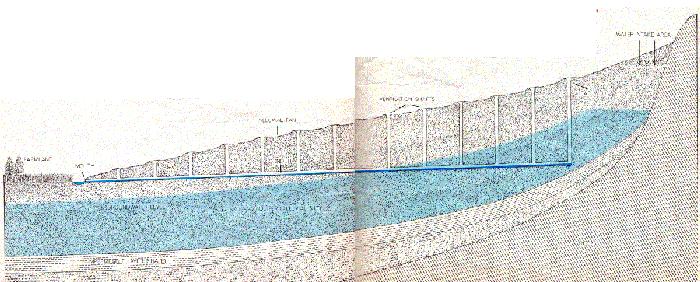

Figure 1: UNDERGROUND AQUEDUCT conveys water gently downhill from the highlands to distribution canals in the and plain below. The water source is the head well (right), which reaches down to the water table. The other shafts provide ventilation and give access for cleaning and repair of the conduit tunnel below. Called qanats after the Semitic word meaning “to dig,” the irrigation systems were invented in Persia during the first millennium B.c. The horizontal tunnel of the qanat is commonly from six to 10 miles long (Picture from CAIS).

The qanat system consists of underground channels that convey water from aquifers in highlands to the surface at lower levels by gravity. The qanat works of Iran were built on a scale that rivaled the great aqueducts of the Roman Empire. Whereas the Roman aqueducts now are only a historical curiosity, the Iranian system is still in use after 3,000 years and has continually been expanded. There are some 22,000 qanat units in Iran, comprising more than 170,000 miles of underground channels. The system supplies 75 percent of all the water used in that country, providing water not only for irrigation but also for house-hold consumption.

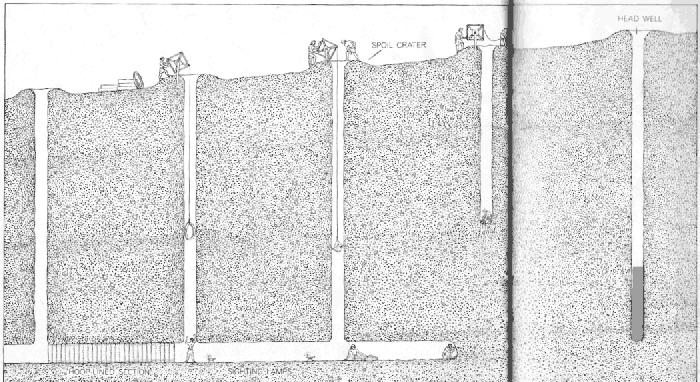

Figure 2: EXCAVATION OF A QANAT begins at the downhill end after a trial well (right) has successfully tapped the uphill water table. Where the gradually sloping tunnel passes through zones of loose earth (left) hoops of tile support the walls, but a tunnel generally lacks masonry except at the discharge point. Ventilation shafts are dug at intervals of 50 yards or so; earth and rock excavated from the tunnel face are winched to the surface through the shafts. Sightings over a pair of oil lamps help to keep the tunnel diggers’ progress on a straight line. A lamp flame that burns badly also gives warning of bad air. Before the tunnelers break through to the head well, men at the surface hail it dry (Picture from CAIS).

Until recently (before the building of the Karaj Dam) the million inhabitants of the city of Tehran depended on a qanat system tapping the foothills of the Elburz Mountains for their entire water supply.

Discoveries of underground conduits in a number of ancient Roman sites led some modern archaeologists to suppose the Romans had invented the qanat system. Written records and recent excavations leave no doubt, however, that ancient Iran (Persia) was its actual birthplace. As early as the seventh century B.C. the Assyrian king Sargon II reported that during a campaign in Persia he had found an underground system for tapping water in operation near Lake Urmia. His son, King Sennacherib, applied the “secret” of using underground conduits in building an irrigation system around Nineveh, and he constructed a qanat on the Persian model to supply water for the city of Arbela. Egyptian inscriptions disclose that the Persians donated the idea to Egypt after Darius I conquered that country in 518 B.C. Scylax, a captain in Darius’ navy, built a qanat that brought water to the oasis of Karg, apparently from the underground water table of the Nile River 100 miles away. Remnants of the qanat are still in operation. This contribution may well have been partly responsible for the Egyptians’ friendliness to their conqueror and their bestowal of the title of Pharaoh on Darius.

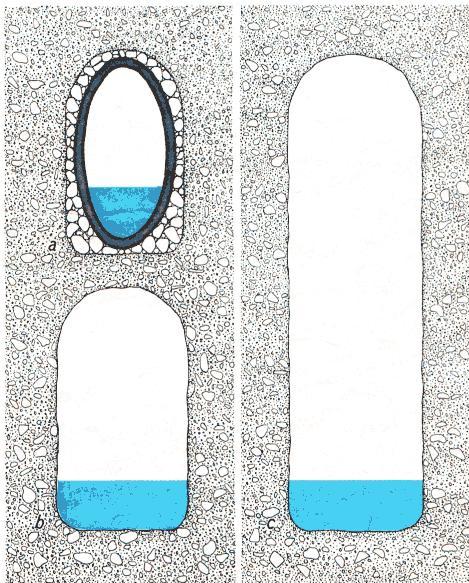

Figure 3: TUNNEL CROSS SECTIONS indicate some of the variations possible in qanat conduits. The tunnel walls may be strengthened with tile hoops (a) or where the tunnel passes through clay or well-compacted soil the walls may be left unlined (b). If the head well should go dry and therefore need to he dug deeper, the conduit would also need to be deepened (c) (Picture from CAIS).

References to qanat systems, known by various names, are fairly common in the literature of ancient and medieval times. The Greek historian Polybius in the second century B.C. described a qanat that had been built in an Iranian desert “during the Persian ascendancy.” It had been constructed underground, he remarked, “at infinite toil and expense … through a large tract of country” and brought water to the desert from sources that were mysterious to “the people who use the water now.”

Qanats have been found throughout the regions that came within the cultural sphere of ancient Persia: in Pakistan, in Chinese oasis settlements of Turkistan, in southern areas of the U.S.S.R., in Iraq, Syria, Arabia and Yemen. During the periods of Roman and then Arabian domination the system spread westward to North Africa, Spain and Sicily. In the Sahara region a number of oasis settlements are irrigated by the qanat method, and some of the peoples still call the underground conduits “Persian works.” In the Middle East several particularly interesting qanats constructed by Arab rulers of early medieval times have been excavated. In A.D. 728 the caliph of Damascus built a small qanat to supply water for a palace in the country. A century later the caliph Mutawakkil in Iraq likewise constructed a qanat system, presumably with the aid of Persian engineers, that brought water to his residence at Samarra from the upper Tigris River 300 miles away.

Figure 4: REMAINS OF PERSEPOLIS, the ancient capital of Persia built by Darius in 520 B.C., are am the center of the aerial photograph on the opposite page. The rows of small holes resembling pockmarks reveal the presence of several qanat systems below the surface: each hole is the top of a ventilation shaft. Most of the qanats around the ruins of Persepolis were built only a few decades ago (Picture from CAIS).

Thanks to detailed descriptions by several early writers, we have a good idea of the techniques used by the original qanat builders. Vitruvius, the first systematic historian of technology, gave an account of the qanat system in technical detail in his historic work De Architectura (about 80 B.C.). In the ninth century A.D., at the request of a Persian provincial governor, Abdullah ibn-Tahir, a group of writers compiled a treatise on the subject titled Kitab-e Quniy. And about A.D. 1000 Hasan al-Hasib, an Arabian authority on engineering, wrote a technical work that fortunately is still available and gives surprisingly good details of the construction and maintenance of the ancient qanats.

The methods used in Iran today are not greatly different from the system devised thousands of years ago, and I shall describe the system as it can now be observed. The project begins with a careful survey of the terrain by an expert engaged by the prospective builders. A qanat system is usually dug in the slope of a mountain or hillside where material washed down the slope has been deposited in alluvial fans. The surveyor examines these fans closely, generally during the fall, looking for traces of seepage to the surface or slight variations in the vegetation that may suggest the presence of water sources buried in the hillside. On locating a promising spot, lie arranges for the digging of a trial well.

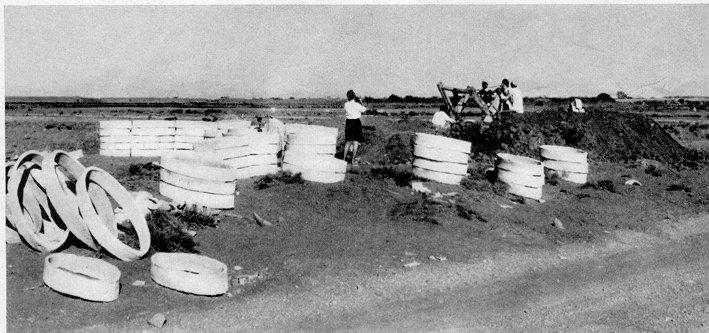

Two diggers, called muqanni, take up this task. They set up a windlass at the surface to haul up the excavated material in leather buckets and proceed to dig a vertical shaft about three feet in diameter, one man working with a mattock and the other with a short-handled spade. As they load the spoil in the buckets, two workers at the surface pull it up with the windlass and pile it around the mouth of the shaft. If luck is with them, the diggers may strike an aquifer at a depth of 50 feet or less. Sometimes, however, they dig down 200 to 300 feet to reach water, and this necessitates installing a relay of windlasses at stages 100 feet apart on the way down.

When they arrive at a moist stratum – a potential aquifer – the diggers scoop out a cavity to its impermeable clay bottom, and for the next few days the leather buckets are dipped into the hole periodically to measure the rate of accumulation of water in it. If more than a trickle of water is flowing into the hole, the surveyor can conclude that he has tapped a genuine aquifer. He may then decide to sink more shafts into the stratum in the immediate area to determine the extent of the aquifer and its yield.

Figure.5: WINDLASS CREW, sheltered from the sun by an improvised tent, raises a load of accumulated silt in the process of cleaning a qanat conduit tunnel. Standing beside the tent is a child who is needed on this job because the ventilation shafts are smaller than usual (Picture from CAIS).

The surveyor next proceeds to chart the prospective course of an underground conduit through which the water can flow from this head well or group of wells to the ground surface at some point farther down the slope. For the downward pitch of the conduit he selects a gradient somewhere between one foot in 500 and one in 1,500; the gradient must be slight so that the water will flow slowly and not wash material from the bottom of the conduit or otherwise damage it. For his measurements the surveyor uses simple instruments: a long rope and a level. (The ninth-century treatise Kilab-e Quniy described a tubular water level and a large triangular leveling device with a plumb that was then employed in this task.) The surveyor lets the rope down to the water level in the well and marks the rope at the surface to show the depth. This will be his guide for placing the mouth of the conduit; obviously the mouth must be at some point a little below the water level indicated by the rope. A series of vertical shafts for ventilation will have to be sunk from the surface to the conduit at certain measured intervals (perhaps 50 yards) along its path. Consequently the surveyor must determine the depth from the surface for each of these shafts. He uses a level to find the drop in the ground slope from each shaft site to the next and marks the length of this drop on the rope. This tells him how far down from the surface each shaft would have to be dug if the conduit ran a perfectly level course. He then calculates the additional depth to which each should be dug (in view of the prospective pitch of the conduit) by dividing the total drop of the conduit from the well’s water level to the mouth by the number of proposed ventilation shafts.

As the muqanni proceed to dig the conduit itself, guide shafts are sunk to the indicated depths at intervals of about 300 yards to provide information regarding the route and pitch of the conduit for the diggers. They start the excavation of the conduit from the mouth end, digging into the alluvial fan. To protect the mouth from storm-water damage they often line the first 10 to 15 feet of the tunnel with reinforcing stone. The conduit is about three feet wide and five feet high. As the diggers advance they make sure they are following a straight course by sighting along a pair of burning oil lamps. They deposit the excavated material in buckets at the foot of the nearest ventilation shaft, and it is hauled up by their teammates above. The tunnel needs no reinforcement where it is dug through hard clay or a coarse conglomerate that is well packed. When the muqanni come to a boulder or other impassable obstacle, they turn around it and then must recover their bearing toward the next ventilation shaft. They show a good deal of skill in this, relying partly on their sense of direction and partly on listening for the sounds of the diggers working on the vertical shaft ahead. The greatest danger encountered by the muqanni is sandy, soft, friable or otherwise unstable soil, which may cause the roof of the tunnel to collapse on them. In such passages the diggers generally line the excavation with oval hoops of baked clay as they cut away the face of the work. Gases and air low in oxygen also are hazards; the diggers carefully watch their oil lamps for warning of the possibility of a suffocating atmosphere. As the rnuqanni approach the aquifer they must be alert to another danger: the possible flooding of the tunnel by a sudden inrush of water. This hazard is particularly great at the moment of breakthrough into the head well; the well must be emptied or tapped very cautiously if the men are not to be washed down the conduit by a deluge. Because of these hazards muqanni call the qanat “the murderer.” A muqanni always says a prayer before entering a qanat, and he will not go to work co a day he considers unlucky.

Depending on the depth of the aquifer and the slope of the ground, qanats vary greatly in length; in some the conduit from the head well to the mouth is only a mile or two long, and at the other extreme one in southern Iran is more than 18 miles long. Commonly the length is between six and 10 miles. The water discharge obtainable from individual qanats also varies widely. For example, of some 200 qanats in the Varamin plain southeast of Tehran the largest yields 72 gallons per second and the smallest only a quarter of a gallon per second.

Figure 6: TILE HOOPS are piled up near one of the vertical shafts that lead to the conduit tunnel of a qanat under construction in rural Iran. Their presence indicates that the construction crew has encountered a zone of loose earth and must shore up the tunnel walls (Picture from CAIS).

Not until the qanat has been completed and has operated for some time is it possible to determine whether it will be a continuous “runner” or a seasonal source that provides water only in the spring or after heavy rains. Because the initial investment in construction of a qanat is considerable, the owner and builders often resort to probing and laborious devices to enlarge its yield. For example, they may extend branches from the main conduit to reach additional aquifers or excavate the floor of the existing conduit in order to lower it and tap water at a deeper level

[see illustration at right on page 97]. A great deal of care is also given to the maintenance of the qanat. The ventilation shafts are shielded at the top with crater-like walls of spoil and sometimes with hoods to prevent the inflow of damaging storm waters. Muqanni are continually kept employed cleaning out silt that is washed into the conduit from the aquifer, clearing up roof cave-ins and making other repairs.As is to be expected of a system that has existed for thousands of years and is so important to the life of the nation, the building of qanats and the distribution of the water are ruled by laws and common understandings that are hallowed by tradition. The builders of a qanat must obtain the consent of the owners of the land it will cross, but permission cannot be refused arbitrarily. It must be granted if the new qanat will not interfere with the yield from an existing qanat, which usually means that the distance between the two must be several hundred yards, depending on the geological formations involved. When the par ties cannot agree, the matter is decided by the courts, which normally appoint an independent expert to resolve the technical questions at issue.

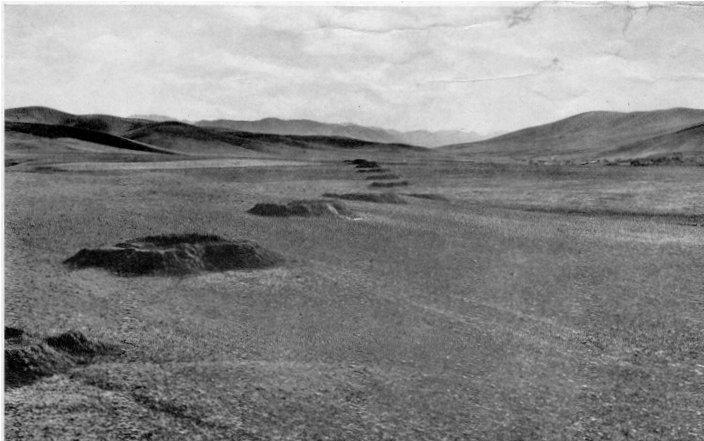

Figure 7: ROW OF CRATERS, each one marking the mouth of a qanat ventilation shaft, runs across an and plain in western Iran. The walls of the craters protect the shafts and the tunnel below from erosion damage from the inflow of water during a heavy desert rainstorm (Picture from CAIS).

Similarly, there are traditional systems for the fair allocation of water from a qanat to-the users. If the qanat is owned by a landowner who has tenant farmers, he usually appoints a water bailiff who supervises the allotment of water to each tenant in accordance with the size of the tenant’s farm and the nature of the crop he is growing. When the peasants themselves own the qanat, as is increasingly the case under the new land reforms in Iran, they elect a trustworthy water bailiff who sees that each farmer receives his just share of the water at the proper time – and who receives a free share himself for his service. The bailiff is guided by an allocation system that has been fixed for hundred of years. For instance, three hamlets in the region of Selideh in western Iran still receive the shares that were allotted to them in the 17th century by the civil engineer in the reign of Shah Abbas the Great. The hamlets of Dastgerd and Parvar are entitled to eight shares apiece and Karton nine shares, and these allocations are built into the outlets from the qanat distribution basin: the outlets at Dastgerd en and Parvar are eight spans wide and the one at Karton is nine spans wide.

The agricultural production made possible by the qanats amply repays the investment in construction and maintenance. My own recent inquiries showed that the return on these investments in value of crops and sale of water ranges from 10 to 25 percent, depending on the size of the qanat, the yield of water and the kind of crop for which it is used. A qanat about six miles long between $13,500 and $34,000 to build, the cost varying with the nature of the terrain. For a qanat 10 to 15 miles long the cost runs to about $90,000.

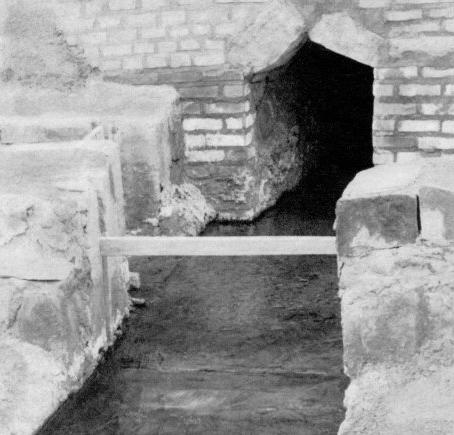

Figure 8: MASONRY MOUTH of an Iranian qanat is equipped with a pair of sluice gates that allow diversion of the water into separate canal systems. The amount of qanat water that may be allotted to village or individual is sometimes determined by decisions made centuries ago (Picture from CAIS).

Construction costs have risen in recent years as the standard of living in Iran improved and labor costs have increased. Moreover, the division of large landholdings into smaller ones under the new land-distribution policy, as well as the introduction of expensive modern machinery has made it difficult for the individual landowners to afford the expense of constructing new qanats or maintaining old ones. Many of these farmers are now drilling wells and using diesel pumps, rather building underground conduits, to bring the water to the surface. Consequently the construction of new qanats may cease, unless the peasants’ newly formed village-cooperatives find it profitable and can raise the necessary capital to built them.

Whatever the future of Iran’s qanat system may be, it stands out today as an impressive example of a determined and hardworking people’s achievement. The 22,000 qanats in Iran, with their 170,000 miles of underground conduits all built by manual labor, deliver a total of 19,500 cubic feet of water per second – an amount equivalent to 75 percent of discharge of the Euphrates River into the Mesopotamian plain. This volume of water production would be sufficient to irrigate three million acres of arid land for cultivation if it were used entirely for agriculture. It has made a garden of what would otherwise have an uninhabitable desert. There are indications that in early times the country had a flourishing vegetation that gradually dried up, partly because of deforestation and the loss of fertile soil by erosion. The Persian people responded to potential disaster with an and farsighted solution that is a classic tribute to human resourcefulness.

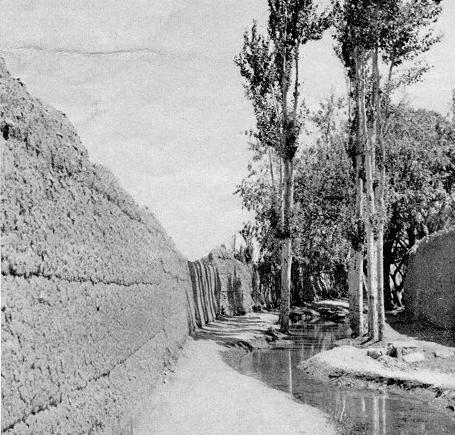

Figure 9: STREAM OF QANAT WATER flows past a wall-enclosed garden in an Iranian villages. The stream first flows through the town and then is diverted into farm irrigation channels (Picture from CAIS).