Kindly note that none of the pictures and accompanying captions printed below appear in the original National Geographic report.

Readers further interested in this domain may consult the below sources:

- Pleistocene to Pre-Achaemenid Eras

- The ancient Civilization of Jiroft

- Jiroft: The Forgotten Civilizational Legacy of Ancient Iran –جیرفت زادگاهی از تمدن جهان– (Video)

- Jiroft and the Aratta Kingdom

- The Jiroft Conference of 2008

- Maymand, an Exemplar Manmade-Cave dwelling

- The Ziggurat of Jiroft: Largest and Oldest of its Type in the World?

======================================================================================

Flooding in 2001 near Jiroft, Iran, exposed the ruins of an ancient necropolis from a Bronze Age culture that flourished alongside Mesopotamia. In 2001 a flood of archaeological objects began appearing in the antiquities market seemingly out of nowhere. For sale were distinctive pieces of jewelry, weapons, finely crafted ceramics, drinking vessels, and game boards—featuring unusual artistry and magnificent inlays of carnelian and lapis lazuli. These extraordinary pieces featured a complex symbology of animals, both wild and domesticated, depicted fighting among themselves or with human figures, the humans always triumphant. There were beautifully realized bucolic scenes of animals grazing in vast palm groves and architectural reproductions of temples or palaces.

TV documentary on the archaeology of Jiroft (Source: Piers Gibbon; Piers Gibbon YouTube).

Data provided by the internet sites and auction houses selling these mysterious pieces was sparse and, at best, vague. Their origins were often listed as “from Central Asia.” At first, it was assumed that the pieces were the work of expert forgers, but as more came on the market in the following months, scholars began to speculate that they could be genuine, deriving from an undocumented site whose location was unknown to them. In 2002 more appeared on the market.

Excavations at Jiroft’s Konar Sandal A, one of the site’s two major mounds, are revealing the base of what may have been one of the world’s largest ziggurats. (Source: Mohammad Eslami-Rad /Gamma in CAIS).

Iranian police solved the mystery later that year. A coordinated investigation led to the arrest of several traffickers and the confiscation of a hoard of artifacts. These objects were being prepared to be shipped from Tehran, Bandar ‘Abbas, and Kerman to buyers around the world. Investigators revealed that most of these distinctive pieces could be traced back to a location in the Halil River Valley, about 25 miles south of Jiroft, a remote and peaceful city in southeastern Iran, not far from the Persian Gulf.

But where did these mystery artifacts come from? At the time, scholars knew of no dig sites in the area, but when they looked closer, they found a simple yet surprising explanation. In early 2001 flooding caused the Halil River to overflow its banks and erode the surrounding lands. Layers of sediment were washed away, and the remains of an ancient cemetery were exposed. Locals and looters quickly recognized the importance of the find and moved to collect and sell the artifacts they were finding.

Chlorite cup from Jiroft, c. 3rd millennium BCE (Source: CAIS). Chlorite vessels similar to the stunning examples recently unearthed at Jiroft in southeastern Iran have been found from the Euphrates to the Indus, as far north as the Amu Darya and as far south as Tarut Island, on the Persian Gulf coast of Saudi Arabia. Iranian-born archeologist Professor Yousef Madjidzadeh speculates that some of these objects were in fact imported from Jiroft, which he is convinced is the legendary third-millennium-BC city of Aratta. Other archeologists, however, dispute this conclusion, maintaining that the vases, bowls and cups from Mesopotamian and Indus Valley sites were manufactured locally. What is clear is that Jiroft traders brought lapis lazuli from Afghanistan and carnelian from the Indus to decorate the ornate vessels they manufactured.

The full import of the discovery became clearer after archaeologists made formal surveys of the area and found that this undocumented culture dated back nearly 5,000 years to the Bronze Age. Looters had ransacked thousands of graves in the necropolis, taking artifacts and damaging the site, but archaeologists were determined to study what remained. They traveled from universities around the world to join an Iranian team to protect as much of the exposed site as possible and excavate nearby areas to learn more about this ancient culture and its people. (History’s first superpower—the Persian Empire—sprang from ancient Iran.)

New Urban Culture

Lasting for several seasons, excavations near Jiroft began in February 2003, under the direction of Iranian archaeologist Yousef Madjidzadeh. Madjidzadeh’s team identified a main necropolis, which they named Mahtoutabad. Most of the initial findings and artifacts are believed to have come from this site despite the looting of grave goods prior to the excavations. Almost a mile to the west of the necropolis, archaeologists targeted for further study two large artificial mounds that rose above the plain.

About a mile apart from each other, the two mounds were named Konar Sandal South and Konar Sandal North. They turned out to contain the remains of two major architectural complexes. The northern mound included a cult building, while in the southern one were the remains of a fortified citadel. At the foot of the mounds, buried under many feet of sediment, were the remains of smaller buildings. It’s believed that the two mounds had once formed part of a unified urban settlement that stretched many miles across the plateau.

“The artists had such a naturalistic way of rendering images,” says Yousef Madjidzadeh, foreground. “It was a style that was not seen anywhere else in that era.” (Source: CAIS). “There must certainly have been a school of stonecarvers, because you see such an aesthetic unity of these objects throughout the kingdom. This high-level artistic quality did not suddenly appear from nowhere,” he maintains. “The traditions must have taken 300 to 400 years to develop.”

Madjidzadeh’s preliminary conclusions from the partial data available made a big impression on the scientific community. Some scholars, most notably American archaeologist Oscar White Muscarella, strongly questioned his findings, sparking furious academic debates. Critics were concerned that the initial looting of the site’s artifacts made it difficult to accurately assess their age and authenticity.

Despite the controversies, work continued at the Iranian site over the course of several seasons with visiting scholars from all over the world, including American archaeologist Holly Pittman from the University of Pennsylvania. The first phase of excavations at the site lasted through 2007.

The initial picture of the Jiroft civilization that existed became clearer. Madjidzadeh published the team’s findings, which suggested that an urban center had been established at the Jiroft site as long ago as the end of the fifth millennium B.C. His optimistic conclusion stated that “the region of Jiroft . . . was a major occupation of urban character in the region during the third millennium B.C. Its center was in the valley of the Halil River where large sites with monumental architecture, sizable craft production areas, domestic quarters, and extensive extramural cemeteries dominated the landscape.”

Archaeologists found distinctive objects—some practical, some decorative, and others sacred—that often featured carved semiprecious stones such as calcite, chlorite, obsidian, and lapis lazuli. The citizens of this city seem to have maintained close contact with cities in Mesopotamia, the region located between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers (roughly coinciding with present-day Iraq). Painstaking excavation of Konar Sandal South revealed that the citadel there had once been surrounded by a monumental wall of brick and had several rooms that through radiocarbon analysis have been dated to between 2500 and 2200 B.C. (These centuries-old windmills in Iran are still turning.)

Partial brick with unique script from Jiroft (Source: Iran Atlas).

Digging at the Jiroft site halted for seven years and began again in 2014 as Iranian archaeologists returned to the site. Scholars from Italy, France, Germany, and other nations have taken part in these new digs, which have been uncovering even more detailed information about the Bronze Age people of Jiroft.

Arts and letters

Archaeologists were thrilled to discover the complexity and beauty of the artworks found at the Jiroft site. The decorative iconography present on hundreds of the vessels is rich with skillfully executed symbolism and shows remarkable similarities with the iconography associated with the Mesopotamian tradition. The scorpion images found at Jiroft echo the scorpion-men depicted in the royal necropolis at Ur (mid-third millennium B.C.). The bull-men of Jiroft call to mind the bull-man Enkidu from the Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh. The parallels are so pronounced that it is theorized that the two cultures could share a common cultural heritage. (Here’s how a self-taught scholar discovered Gilgamesh, the world’s first action hero.)

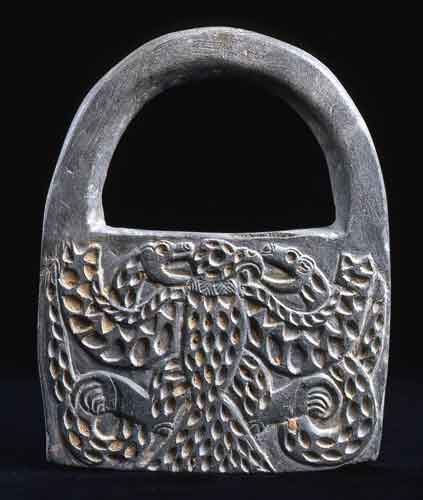

“Handbag” looking artifact with decorative motifs excavated from Jiroft (Source: Iran Atlas). The artefact may have been a weight standard for measurements.

Most striking of all are the recurrent, distinctive images of an inverted bull with an eagle hovering above it and of battles between eagles and snakes. These two motifs appear on many of the vessels found at Jiroft and seem to evoke one of the most famous Mesopotamian myths: that of Etana, the mythical shepherd-king of Kish who is cited on the Sumerian king list, as the first sovereign after the universal flood.

In the myth, one of the most complex and exciting tales from this early period, Etana needs a way to ascend into heaven to attain a magic plant that will allow his wife to give birth to an heir. Meanwhile, an eagle and a serpent struggle; the pair, while once sworn allies, will become mortal enemies after the eagle eats the snake’s offspring. The snake wreaks revenge on the eagle, leaving him to die in a pit. On the advice of the sun god Shamash, Etana saves the eagle, and in gratitude the bird bears Etana up to heaven to retrieve the plant he needs to ensure his succession.

The motif of the universal flood, a central one for the Sumerians and Babylonians, may also appear in some representations from Jiroft. Italian archaeologist Massimo Vidale noted in his work on Jiroft that:

“on a vase, a kneeling character holds two zebu whose heads produce waves. A mountain rises from the waves; another character with the divine symbols of the Sun and the Moon lifts something that looks like a rainbow, beyond which we can see chains of mountains that emerge . . . Although it is essential to be cautious, it is difficult for the writer to leave aside the impression that the image tells an ancient myth about a great flood.” (Explore the ancient water tunnels below Iran’s desert.)

Artifact excavated at Jiroft featuring a scorpion with a human head (Source: Iran Atlas).

In one of the entrances to the citadel of Konar Sandal South, scholars found a fragment from a baked clay tablet inscribed with writing. In another spot, some 500 feet to the north, three other tablets bearing written texts in two different writing systems were found. Whoever these people were, they had a writing system. One of them appears similar to the so-called linear Elamite, a script used in the cities of the kingdom of Elam, on the border with Mesopotamia. The other script was geometric in form and had not been seen before. The obvious inference from the two finds is that the civilization at Jiroft was literate.

Identification ideas

In 2003, after examining the huge collection of confiscated archaeological finds, Madjidzadeh, the director of operations, put forward an intriguing hypothesis. Based on his observations of the site and a study of ancient Mesopotamian cuneiform texts, Madjidzadeh believes that the Jiroft civilization is Aratta, a land that was praised for its wealth in numerous Sumerian poems. An ancient text describes a conflict between Aratta and the Mesopotamian city of Uruk. In the telling, Aratta is a vibrant place:

“battlements are of green lapis lazuli, its walls and its towering brickwork are bright red, their brick clay is made of tinstone dug out in the mountains.”

Jar or vase figure from Jiroft (Source: Iran Atlas).

Madjidzadeh points to the site’s geographical position surrounded by mountains, the abundance of semiprecious stones, and the high degree of civilization as factors in favor of an Aratta identification. Skeptics criticize Madjidzadeh’s theory as lacking in solid evidence. There is no documentary proof to suggest that Aratta existed anywhere outside of the Sumerian poems and that Aratta was just a Bronze Age myth.

Other scholars have theorized that the civilization near Jiroft may correspond to the ancient kingdom of Marhasi. This theory has some textual support. First, there are the inscriptions of the kings of Akkad, a Mesopotamian empire, that describe their glorious Akkadian feats during the fight against a powerful state in the Iranian highlands. In one of these texts, the epilogue of the conflict is narrated in great detail: “Rimush [King of Akkad] defeated Abalgamash King of Marhasi in battle . . . When he conquered Elam and Marhasi he took 30 gold mines, 3,600 silver mines and 300 male and female slaves.” There is firm evidence that the city of Akkad existed between 2350 and 2200 B.C. Since Marhasi was Akkad’s contemporary, Marhasi can also be dated to that time, which lines up with the data from the Jiroft dig sites. Unlike Marhasi, Aratta cannot be identified with a specific period. (Here’s how archaeologists determine the date of ancient sites and artifacts.)

Upright eagle from Jiroft (Source: Iran Atlas).

No one had ever dreamed that from the sands of such a remote and arid region, considered by many to be an unlikely spot for the development of a complex civilization, that a refined culture could emerge. Since excavations began nearly two decades ago, numerous discoveries—once thoroughly analyzed—will make it possible to place Jiroft it in its proper historical perspective. Since 1869, when the remnants of Sumerian culture were uncovered, Mesopotamia has been considered the cradle of civilization. But the remarkable findings at Jiroft demand a reassessment of that interpretation.