The article “The Mother Cuisine: A taste of Persia’s ancient—and influential—cooking” was written by Sarah Kagan for the epicurious.com venue. For readers further interested in this topic may wish to also consult the following resources:

- Nidhi Subbaraman: Early humans in Iran were growing wheat 12,000 years ago

- Brief Notes on Spoons and Forks in Greco-Roman and Ancient Iranian Civilizations

- Iran’s Favorite Dish: the Chelo Kebab

- Notes on Iranian Cuisine

- A Short History of the Iranian Nān (Bread)

- World’s earliest known Wine

- The Mughal Emperor who Loved Melons

- Persian Connections to India’s Samosa

Kiondly note that none of the images and accompanying descriptions printed below appear in the original article written by Sarah Kagan for the epicurious.com venue.

======================================================================================

Iran is such a hot-button issue these days that it can be hard to look at the country outside of the geopolitical context. But no one interested in food can afford to ignore what is one of the world’s most important and influential cuisines.

Originally discovered at a Neolithic village site in Iran, this jar was one of six vessels containing the remains of 7,000-year-old wine (Source: Archaeology.org and The University of Pennsylvania Museum). As noted by Amy Ellsworth of the University of Pennsylvania Museum page (July 18, 2012): “The practice of wine-making or viniculture can be traced back to the Neolithic period, 7,000 years ago when the first Eurasian grape vines were domesticated for this purpose. This “Wine Jar” was found at Hasanlu in Hajji Firuz, Iran. It has been reconstructed from multiple fragments. The jar is one of a series of jars found sunken into the floor along an interior wall of a “kitchen” in a well-preserved Neolithic house at HF Tepe in North West Iran. The jar had a capacity of approximately 9 liters (2.5 gallons). It is the oldest known wine storage container in the world. Analyses of the two jars in the Penn Museum showed that they had contained a resinated wine or “retsina,” i.e., with terebinth tree or pine resin added as a preservative and medical agent. There was a red to go with the white wine, based on the colors of the residues.”

Iranian cooking is heir to no less than two and a half thousand years of saffron- and rosewater-scented history. The foods of the courts of ancient Persia (as Iran was called until the 1930s) included perfumed stews flavored with cinnamon, mint, and pomegranates; elaborate stuffed fruits and vegetables; and tender roasted meats — dishes that have influenced the cooking of countries as far-flung as India and Morocco. In many ways, Persian food is the original mother cuisine.

The diversity of Persian cuisine as displayed in the Ariana restaurant in London, England (Picture Source: Ariana Restaurant).

Legacy of Empire

The history of Iranian cooking goes back to the sixth century B.C., when Cyrus the Great, the leader of a tribe called the Pars (Persians), created an empire that eventually stretched from India to Egypt and parts of Greece.

Achaemenid silver spoon with a curved swan’s head handle discovered at Pasargadae (mid-500s century BCE) (Source: David Stronach & Hilary Gopnik, Encyclopedia Iranica).

This vast, unified territory became a conduit of culture and cuisine, and native Persian ingredients such as saffron and rose water were spread throughout the empire.

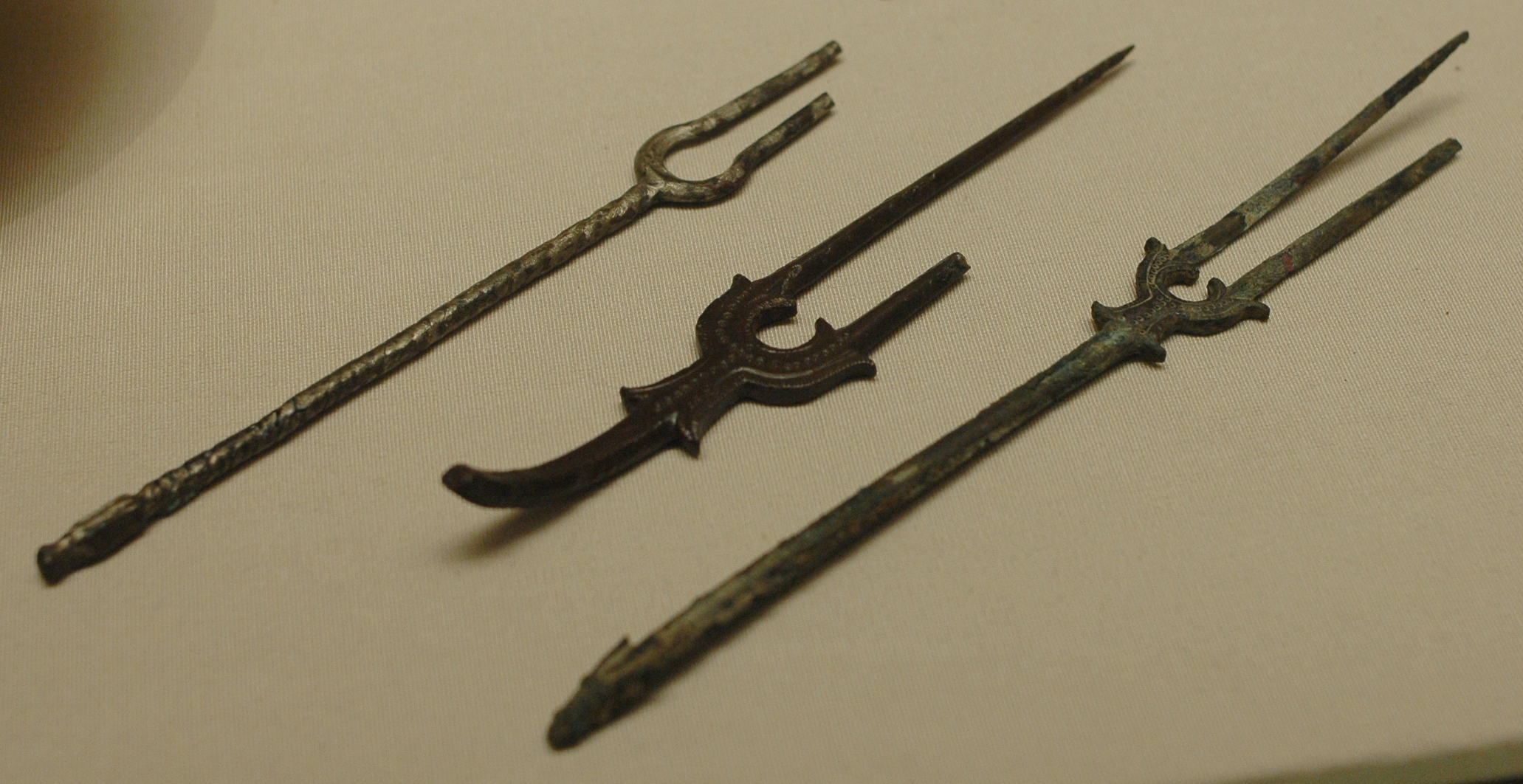

Iranian bronze forks dated from the 8th – 9th centuries CE (post-Sassanian era) housed at the Louvre Museum in Paris (inventory MAO 421-422-431) (Source: Public Domain, photographed by Marie-Lan Nguyen).

The Persians also traded with the kingdoms of the Far East: Caravans traveling along the Silk Road from China to present-day Syria brought citrus fruits, eggplants, and rice from Asia to the Middle East and the Mediterranean.

A vegetarian delight: the Dolmeh Kadoo (stuffed squash in the Persian style) (Picture Source: My Persian Kitchen).

The Persian empire eventually fell to Alexander and later to the Arabs (who converted the Persians to Islam), but each successive wave of rulers proved fond of the Persians’ flavorful cooking. The Arabs even brought Persia’s distinctive sweet-and-sour flavors to North Africa, and in the Middle Ages, exotic Persian techniques such as gilding (painting foods with elaborate gold or silver leaf) traveled to Europe via the Crusades, becoming all the rage at regal banquets.

From the 11th to 15th centuries A.D., Persian culture flourished despite Turkish and Mongol rule. This era saw a flowering of native poetry and art, and its rarified cooking, with rich sauces and pilafs strewn with nuts and dried fruit, became the foundation of the Moghul cuisine of northern India.

Living History

Contemporary Persian cooking wears its heritage on its sleeve. Rice has a place of honor, prepared with a prized, golden crust formed from clarified butter, saffron, and yogurt.

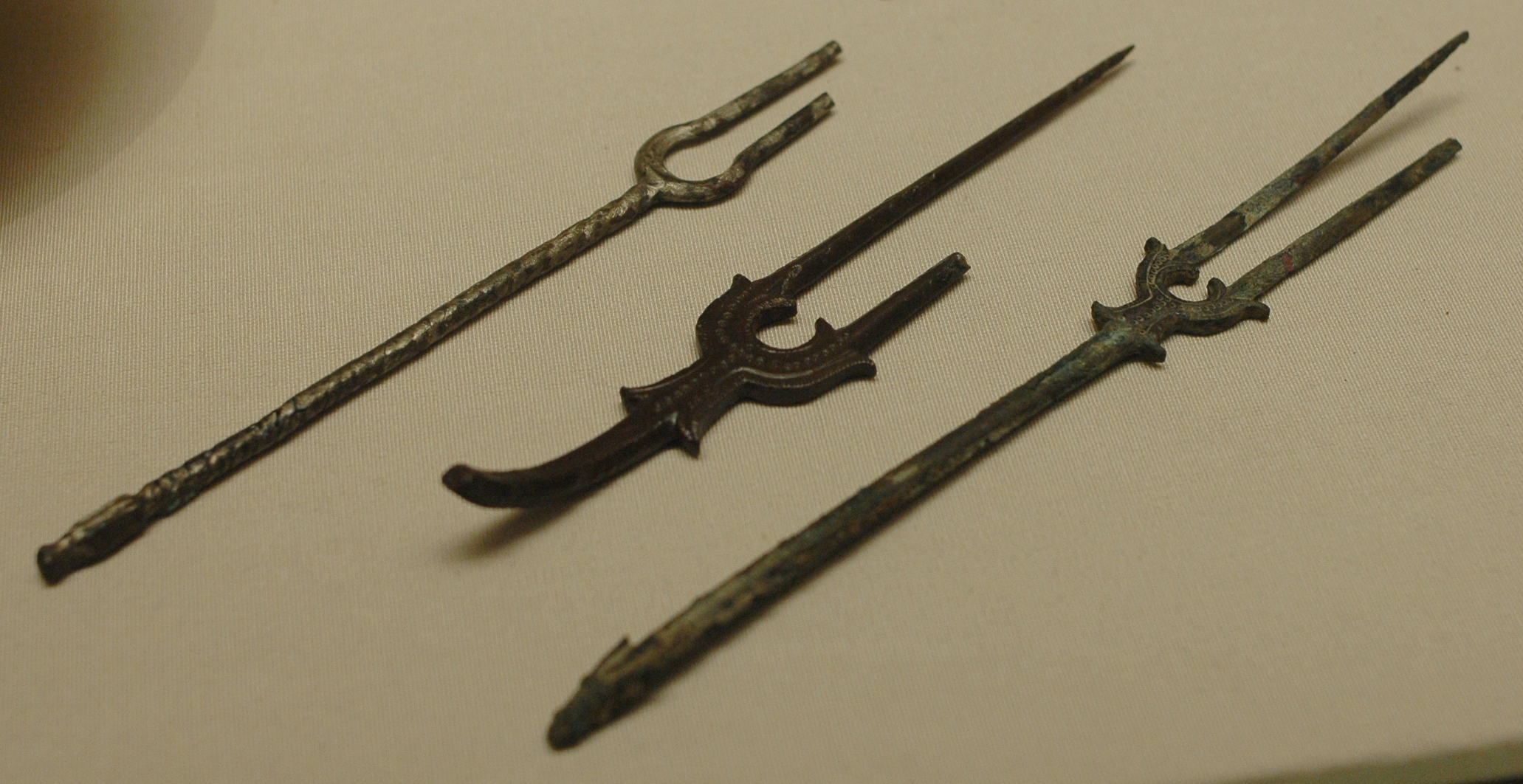

The Tahdig delicacy crust shaped around the rice in the form of a cake (Picture Source: YumSugar). There are in fact a large varieties of the Tahdig.

Lamb and chicken are marinated and grilled as kebabs, or mixed into stews called khoreshes with fruit and sour ingredients such as lime juice.

A serving of Čelow-kabāb-e kūbīda (Picture Source: Akbar Joojeh Restaurant, Thornhill, Ontario).

Cinnamon, cardamom, and other spices are used in great abundance, along with a multitude of fresh herbs, and pickles and flatbreads are served at every meal.

A bowl of Ash-e Anar known for its unique taste made with pomegranates (Picture Source: Public Domain).

Desserts feature rose water and pistachios, and refreshing drinks called sharbats are made from diluted fruit and herb syrups.

A sample of a wide range of Persian delicacies and desserts (Picture source: cestsibonbakery.com).

Though largely unknown in the U.S., Persian food is perfect for American palates primed by its Middle Eastern and Indian cousins.

Sabzi-polo Mahi (vegetable-seasoned rice and north-Iranian style fish filet) (Picture Source: Phancouver).