The article “The U.S. once had a friendship with Iran born in Philadelphia” was written by John Ghaznavian for The Philadelphia Inquirer news outlet on September 20, 2021. Kindly note that the images and accompanying captions printed below do not appear in the original Philadelphia Inquirer publication. John Ghaznavian is indeed commended for this article which will hopefully be more widely distributed and appreciated.

Addendum … Readers are cautioned in general that the term “Middle East” cited in the article (and Western and Iranian outlets in general) is a relatively recent (Anglo-European) geopolitical invention with its validity being questionable with regards to cultural, historical, linguistic, etc. factors. For more on this topic, kindly consult the following articles:

- Farrokh, K., & Vasseghi, Sh. (2017). The “Middle East”: An Invented Term from the 20th Century. Persian Heritage, 88, pp.12-14.

- The “Middle East“: A 20th Century Neologism that has Run its Time?

====================================================================================

Amid another chaotic news cycle from Afghanistan risking oversimplifications of the “Middle East”, it’s worth reexamining U.S.-Iran relations.

The long and tumultuous history between the United States and Iran has an unexpected birthplace: Philadelphia. It was here, in the early 1720s, that the American Weekly Mercury — the first newspaper ever published in this city, and one of the first in the American colonies — introduced American readers to the concept of the “Persian Empire” (as Iran was known then). The picture it painted — of a benevolent, idyllic kingdom in the midst of a troublesome Middle East — is perhaps not what we would expect, from our current vantage point. But it was a picture that would come to shape and dominate American impressions of Iran for the next two and a half centuries. Today, as tensions persist between the two countries over Iran’s nuclear program, it is a picture worth revisiting.

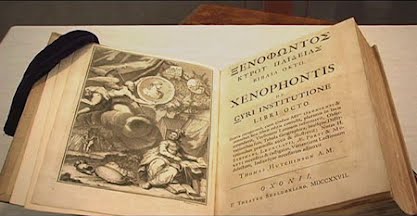

Thomas Jefferson’s copy of the Cyropaedia (Picture Source: Angelina Perri Birney). Like many of the founding fathers and those who wrote the US Constitution, President Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) regularly consulted the Cyropedia – an encyclopedia written by the ancient Greeks about Cyrus the Great. The two personal copies of Thomas Jefferson’s Cyropaedia are in the US Library of Congress in Washington DC. Thomas Jefferson’s initials “TJ” are seen clearly engraved at the bottom of each page. For more on this topic see … Ancient Persian Ruler influenced Thomas Jefferson, U.S. Democracy …

To say that colonial-era Philadelphians were obsessed with Iran would be an understatement. Week after week, in the 1720s, the American Weekly Mercury competed with its archrival, the Boston News-Letter, to bring Philadelphians the latest news from the Persian Empire — sometimes devoting 20%-30% of its column inches to Iran. One issue of the Mercury, from July 1724, led with the regretful note: “We [do not] hear any thing from Persia” this week — a startling reminder that in the American colonies in the 1720s, the mere absence of news from Iran was a front-page story. In 1727, the Mercury even launched a special nine-part series, full of wild, sensationalist coverage about noble Iranians being preyed on by savage Afghans. It was the first time an American newspaper had tried a format like this, and it was a runaway success.

Shah Abbas I (r. 1587-1629) as depicted in a European copper engraving made by Dominicus Custos citing him as“Schach Abas Persarum Rex” or “Shah Abbas the Great monarch of Persia”. Note how Custos makes a particular emphasis on linking Shah Abbas to the “Mnemona Cyrus” (the Memory of Cyrus the Great of Persia). His victories over the Ottomans weakened them against the Europeans to the West, and especially in the Balkans and Eastern Europe.

Why this early American love affair with Iran? There were numerous reasons, religious as well as political. Persia occupied a special place in the Bible, as the land of Cyrus the Great, liberator of the Jews from Babylonian captivity, as well as the three Magi (the wise men from “the East” were likely Persian Zoroastrian priests).

A Byzantine depiction of the Three Wise Men (526 CE), Basilica of Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, Italy. (Source: Public Domain). For more on this topic see The Mysteries of the Three Kings: Who Were They and Where Did They Come From? …

Persia was also the archrival of the Ottoman Empire, which had possessed the Holy Land for centuries and which colonial Americans saw as the greatest threat to Christian civilization. So naturally, in 1722, when the Afghans revolted against their Persian rulers, bringing an end to the glorious empire of the Safavid dynasty, and sacking its legendary capital, Isfahan, Americans were convinced the Ottomans were secretly aiding the rebellion (they weren’t) and began cheering on the Persians. Again and again, the Mercury blasted the “wicked” Afghans and their (supposed) Ottoman backers — the first example of the American media reducing Middle Eastern actors to good guys and bad guys. Readers were told that, because the Afghans and Ottomans were both Sunni, they must have forged a crude axis of evil against poor, innocent, Shia Persia. It was complete nonsense. But the Shia were quickly portrayed as less Muslim somehow, less evil than the dominant Sunni.

Iranian ambassador Reza Beg enters Paris to a warm welcome by the local French populace. Note the banner with the Lion and Sun motif carried by the standard bearer or “Alamdar-Bashi” (Consult Herbette, 1928, pp. 115, original from the Cabinet des Estampes).

Why does this history matter? Because this image of Iran — the benevolent, exotic kingdom surrounded by a sea of evil — remained surprisingly persistent in the United States, decade after decade, and never truly disappeared until the Iranian Revolution of 1979 ousted the pro-American Shah and ushered in a more fanatical Islamic Republic under Ayatollah Khomeini. As late as December 1977, just one week before the revolution broke out, President Jimmy Carter stood raising a glass at a banquet in Tehran and toasted Iran as an “island of stability in one of the more troubled areas of the world.” It was the standard way that Iran was talked about in Washington at the time. But it was also the culmination of more than 250 years of American idealization and admiration of the Persians.

A detail of the painting “School of Athens” by Raphael 1509 CE (Source: Zoroastrian Astrology Blogspot). Raphael has provided his artistic impression of Zoroaster (with beard-holding a celestial sphere) conversing with Ptolemy (c. 90-168 CE) (with his back to viewer) and holding a sphere of the earth. Note that contrary to Samuel Huntington’s “Clash of Civilizations” paradigm, the “East” represented by Zoroaster, is in dialogue with the “West”, represented by Ptolemy. Prior to the rise of Eurocentricism in the 19th century (especially after the 1850s), ancient Persia was viewed positively by the Europeans. For more see Ken R. Vincent: Zoroaster-the First Universalist …

Nor, incidentally, did the feeling only go in one direction. The history of U.S.-Iran relations is littered with mutual admiration, mutual idealization, and mutual fascination — at least until the end of the 1970s. And on the U.S. side, this feeling was born here in Philadelphia. But it has completely disappeared since.

The Americans of Urumia: Iran’s First Americans and their Mission to the Assyrian Christians” by Hooman Eslami provides a rare and long-overdue academic study into the arrival and works of the first Americans and their families into Iran in the early 20th Century.

No one today would be naive enough to suggest that all this can easily be reclaimed or revived. Tehran and Washington, after all, have accumulated more than 40 years of mutual hatred since they broke off relations in 1980. But the spirit of early Philadelphia may still have something to teach us about the long, complicated — and sometimes surprisingly positive — history of U.S.-Iran relations.

Iranians holding candlelight vigil in Tehran’s Mohseni Square on September 18, 2001 in support of the victims of September 11 attacks at the New York World Trade Center (Sources: Best Iran Travel and Tehran24.com). The only country in the West Asia region where spontaneous candlelight vigils were held for victims of the World Trade Center Attack on 9/11 was Iran. This event was simply ignored by the western media. At this juncture a simple question may be raised: what was the purpose behind the Western Media (BBC, CNN, ABC News, CBS, etc.) silence regarding this event? It is notable that no candlelight vigils were held in those countries in the West Asia region which the Western media portrays as “friends” of the West and the United States – these include Saudi Arabia (where the majority of the 911 hijackers were from), Kuwait, etc. One can imagine the impact such reports would have had on American and western public opinion in general. It certainly would cause cognitive dissonance to see such images as Iranians in particular are (a) simplistically conflated with the current government in place since 1979 (b) often portrayed as negative propaganda targets in popular entertainment and the news media. The above images are inconsistent with the negative views that have been carefully crafted and cultivated since 1979.

In the midst of another chaotic news cycle from Afghanistan risking many oversimplifications of the “Middle East”, perhaps it is worth pausing to remember that no hatred — and no tightly held belief about one’s friends and enemies — lasts forever.

French citizen “Eric” plays the unofficial Iranian national anthem “Ey Iran” with his cello in a passageway in the city of Lille (Source: Mahnaz Payman in YouTube). Eric has traveled to Iran, studying its culture, history and language – note that he also sings the Persian words to the anthem he performs with his cello. Despite negative propaganda spanning for decades (or centuries if we consider historiography from the 19th century) a very notable number of European and Anglo-American citizens choose to go past the select narratives of media, entertainment and academia.