The text printed below has been slightly edited from its original version. Kindly note that the first image and accompanying caption below does not appear in the original Electrum Magazine publication.

==================================================================================

In the Palazzo Normanni of Palermo, the uniquely famous gold background mosaics of the Salle di Roger were designed by artists who either consciously or unconsciously evoked Sassanian Persian motifs that were also known from earlier Byzantine and imported silks. The Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE) followed the Parthian Empire in controlling much of Mesopotamia and ancient Persia, vigorous enough to more than stave off Roman domination. Several Roman emperors met defeats at the hands of Sassanians, including Valerian, Gordian III, and Philip the Arab by Shapur I in the 3rd century CE. The Sassanians had their capital at Ctesiphon in present day Iraq. The first Sassanian king Ardashir (224-241) set the course for Sassanian independence for the next 400 years, effectively melding Mesopotamian and Persian elements and controlling the central Silk Road routes.

A reconstruction of Ctesiphon as it may have appeared in the 6th and early 7th centuries CE (Source: Sunrisefilmco.com in Pinterest). For more on Ctesiphon, click here …

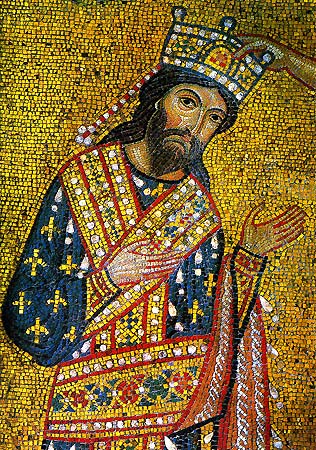

Sassanian monopoly on silk mobility to the West stymied Byzantine efforts to acquire silk at reasonable costs and it wasn’t until near the end of the Sassanian Empire, around 563 AD, that Justinian in Constantinople was able to surreptitiously begin a Byzantine silk industry. The Sassanian empire ended with the Arab invasions in the middle 7th century that brought Islam to the region ending Persian rule. Famous for their textiles and especially their silk designs, which were distinct even while incorporating Sogdian and Bactrian patterns. These patterns have rondels often surrounded by pearls and dual animals facing each other in symmetry. In 11th century Sicily the Rogerian Dynasty, after conquering the Moslem caliphate, established one of the most benevolent and religiously tolerant partnerships ever seen before and after allowing for a modicum of Moslem self government, including the office of sheriff (sharif) and mudrasas. Jewish officials were also part of the administration and they did not serve only the considerable Jewish population, but also the full Sicilian government. Thus both Moslem and Jewish elements served alongside Latin Norman Christian officers in the Sicilian court. Trilingual inscriptions in Latin, Arabic, and Hebrew adorned Palermo. Roger II (1095-1154) even brought the renowned Arab geographer and scholar al-Idrisi from Andaluz (Moorish Spain), who compiled several encyclopedias for the Sicilian court. This wise and tolerant regime in Palermo alienated only the intolerant for several generations. The brilliant Norman king of Sicily, Frederick II (1194-1250), last great Rogerian ruler and Holy Roman Emperor also known as the wonder of the world, Stupor Mundi, usually ran afoul of the Church for his refusal to expel Muslims and Jews from his cosmopolitan court.

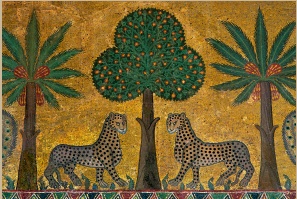

Mosaic vault from the Roger Rooms of the Norman Palace, 12th c. (Photo: Electrum Magazine & Public Domain).

Medieval silk vestments and even shrouds often displayed Sassanid motifs even when loomed and embroidered long after the Sassanid Empire. For example, the silk shroud of St. Sernin of Toulouse, 12th century from Al Andaluz (Moorish Spain), and now in the Cluny Museum in Paris, represents two Sassanian peacocks facing each other across a Tree of Life.

Silk Shroud fragment of St. Sernin of Toulouse, 12th c. from Andaluz (Moorish Spain), Cluny Museum, Paris (Photo: Electrum Magazine & Public Domain).

Other examples include the Reliquary of St. Len at the Victorian Albert in London as well as other silk and textile fragments whose motif and style were borrowed from Sassanian art long after its own floruit was forgotten or possibly never really k own in the West. That Al Andaluz, Moorish Spain, would preserve some of this imagery is no surprise given the Alhambra and other Moorish mudejarelements still preserved in Cordoba and elsewhere that earlier came across North Africa from further East. Architecturally, Islamic architects also helped to create some of the first churches, like San Giovanni Degli Eremiti in the 11th-12th century with conversions of fours sided towers to eight sided pendentives to domes, also seen in San Giovanni Degli Lebbrosi as well as the La Zisi Palace. Elsewhere Islamic influences can be seen in Palermo’s Cathedral, especially its apse and Monreale Cathedral with its apse and mave. The Norman Palace in Palermo also shows Islamic architectural influence, especially in its arcades and the royal suites of the kings. Equally inclusive the churches of Sicily, especially in Palermo, also employed Greek mosaicists to render many gold tessera backgrounds as would be seen in Byzantine churches.

Sassanian Textile from 6-8th c. CE (Photo: Julianna Lees for Electrum Magazine).

In the Norman Palace rooms of Roger II and William II, the Arabic arched vaults contain Sassanian influenced mosaics in multiple tiers. All of the mosaics are gold backed and gleam with beautiful reflected light. One upper tier contains lemon trees and Saggitarius-like centaur archers facing each other with a date palm tree in between them. A lower tier, moving inward, again has lemon trees, peacocks, date palm trees, and finally at center, two leopards face each other under a tree laden with oranges. Yet another tier has archers on the outside but moving in, date palm trees and great horned stags facing each other with a central lemon tree. In its Arab arched vaults, a last tier has two peacocks facing each other as they feed from a central date palm tree. Seeing the citrus trees visually, would remind viewers of fragrant lemon groves spreading over the valley just south of the palace.

Sassanian style Mosaic from Salle Roger II / William II, Norman Palace (Photo: Electrum Magazine & Public Domain).

All these mosaics were designed with Sassanian animals and created by Byzantine, Greek, and Norman Latin skilled artists. In this way, the best of the different medieval cultures here in Sicily – Norman, Greek, and Near Eastern – embellished the Rogerian Dynasty spaces in the most cosmopolitan style of Sassanian animal symmetry.

Roger II King of Sicily (1095-1154) (Photo: Electrum Magazine & Public Domain).

These beautiful mosaics backed in gold tesserae at the Norman Palace are the perfect expression of the hybridized art that drew from all over the world in that brief period of enlightened and tolerant Sicilian Norman kings, the likes of whom have not been seen again.

Islamic (Sassanian-based) Architecturally-influenced Norman Palace, Palermo (Photo: Electrum Magazine & Public Domain).