The article “KING ARTHUR (Part II): Some literary, archaeological and historical evidence” is written by Periklis Deligiannis. This is a continuation of Part I which was posted by Kaveh Farrokh.com on August 31, 2019. The version printed below contains a number of images and accompanying captions that do not appear in Deligiannis’ original posting.

Kindly note that the Iranian identity of the Scythians, Sarmatians and Alans readers are referred to the following sources:

O. Basirov: The Origin of Pre-Imperial Iranian Peoples

V. I. Abaev & H. W. Bailey: The Alans

====================================================================

Arthur’s warriors are described as knights. Some scholars believe that this description is due only to the fact that in the time of Geoffrey of Monmouth, every hero had to be a knight. But this view is rather superficial and incorrect because there is clear evidence that in the 5th-6th centuries, the Romano-Britons had a strong heavy cavalry, which probably was their main military striking force. The cataphract (heavy armoured) Sarmatian cavalrymen were in fact the first knights of the European history, the founders of European Chivalry according to the most popular view.

Sarmatian sword with the distinctive ring-type handle ending. A leather strap was probably tied in the ring and in the hand of the warrior as well, in order to prevent the loss of the sword during combat (Source: Periklis Deligiannis).

The Sarmatian armies included among other types of combatants, many cataphract cavalrymen protected (like their horses) with nearly full-length metal armor (usually scale armor). They also included many horse-archers and horse-spearmen without any cuirass. The cataphracts fought mainly as lancers with a long heavy spear (like the subsequent European knights) as their main offensive weapon. They were also carrying a composite bow, a long sword and a dagger. The familiar to us, figure of the Late Medieval European knight was created when the East Germanics (Goths, Vandals, Burgundians), the Suebi Germanics (Marcomanni, Longobards/Lombards, Quadi) and the Romans adopted the full Sarmatian cavalry equipment. The decimation of the Roman army by the Gotho-Sarmatian cavalry at the battle of Adrianople in 378 AD, established the dominance of the knight (cataphract) during the Middle Ages. The Normans of Northern France were the ones who shaped the final form of chivalry.

At this point, Ι have to make a remark on the origins of the Normans. The Normans are usually described by the modern historians as the descendants of Danish Vikings , but in reality they had little to do with them. Danish ancestry was in fact very limited among the Normans. They were mainly the descendants of the Latinized Gauls (specifically Aulerci and Belgae/Belgians) of the mouth of the Seine who adopted a Scandinavian national name (Normans, meaning the People of the North) mainly for propaganda purposes and also a few Scandinavian elements of culture and warfare. The primary historical donation of the Danes to the Normans was the complete independence of Normandy from France and the subsequent “making” of the Norman national identity. Another racial component of the Norman people were the Sarmatian Alans, as we shall see below.

A spangenhelm, popular to the Sarmatians (many researchers consider it to be of Sarmatian origin), the Later Romans, the Romano-Britons and many barbarian peoples (Goths, Huns, Saxons etc.) (Source: Periklis Deligiannis).

Returning to the Arthurian Era, in Britain, the “knights” of Arthur probably consisted of Latinized and Celtisized descendants of the Sarmatian mercenaries, and of Celtic cavalrymen who fought in the Sarmatian way. The Iazyges (Iazygae) of Bremetennacum are mentioned in the early 5th century as “the army of the Sarmatian veterans“. They probably survived until then as a national entity, even speaking Latin instead of their native Iranian language. Furthermore, almost all of the Sarmatians of the Roman Empire were already Latinized linguistically. It is also certain that many Alans (the most populus Sarmatian tribe) settled in Britain as mercenaries. Some modern scholars have theorized that the modern British personal name Alan and the French or generally Neo-Latin Alain/Alen come from the Alans. When members of this people settled en masse in western Europe and were assimilated by the natives, they turned their national name to a personal name: Alanus in Latin (modern Alan, Allen, Alain, Alen). Large groups of Alans settled as local aristocracies in Northeastern Spain, Northern Africa, Northern Gaul (giving their name also to the region of Alencon), etc.

Iranian-speaking Alan warrior circa 5th century CE. The descendants of the Alans are found in Western and northern Iran as well as the Caucasus and Eastern Europe. Large numbers of Alans also assimilated with Europe’s Germanic tribes, notably the Ostrogoths (Painting by the late Angus McBride).As noted by Professor Abaev and bailey in this article “The name “Alan” is derived from Old Iranian *arya-, “Aryan,” and so is cognate with “Īrān” (from the gen. plur. *aryānām)“.

In the 10th century, the Normans fully adopted cataphract warfare from the local cavalrymen of northern France. The latter had adopted it from the Alan nomads who settled in their region centuries ago and they were partly their ancestors. The Normans won the battle of Hastings (1066) using in reality the ancient nomadic tactic of feigned retreat, executed by the left wing of the Norman cavalry. That wing was manned by Breton Celt cavalrymen (of Northwestern Gaul), who were partly of Alanic origin. The commander of the left wing was the Count of Brittany, Alan the Red (redhead), a name possibly characteristic of his origin. Considering the Count’s red hair, it should be noted that some Chinese and European chronicles describe the Alans of the Central Asian Sarmatian homelands, as having largely blond or red hair. But the Celts are also frequently red-haired and in fact they have the largest rate of redheads in Europe.

A representation of a Draconarius, a Roman standard-bearer of the Late Empire, by the British Historical Association Comitatus. He holds the banner of the Dragon which the Roman army bequeathed to the Romano–British army who confronted the Anglo-Saxons. The dragon was a Saka/Sarmatian symbol (and banner), adopted from China to the Roman Empire.

The standard of the dragon used by Arthur’s army, was a Saka/Sarmatian symbol, adopted from China to the Roman Empire. The Sarmatian cavalrymen brought with them their ‘national banner’, the Dragon, made as an airbag mounted on a wooden shaft. The standard of the dragon had a metal head and red fabric body, which was swelling when the wind was entering it through the dragon’s jaws (which happened at the galloping of the horse). This banner and the arms and armor of the Sarmatians and their horses are strikingly similar to most of the respective characteristics of Arthur and his knights, as they are described in the Medieval sources. The Romano-Briton army had adopted them from the Late Roman army, which however had adopted them from the Sarmatians.

The annomination/last name Pendragon of Uther (Arthur’s father from whom he inherited it) is rather Romano-Sarmatian as well. Pendragon is analyzed in Brythonic Celtic as ‘ap-(en)-dragon’ meaning the “son of the dragon“, referring to the Sarmatian standard. In essence it means “he who fights under the banner of the dragon“, a nostalgic remembrance of the Sarmatian cavalry which formerly protected Britannia from the invaders. Generally speaking, the symbol of the Dragon has an important role in the Arthurian legends.

The name of Lancelot, an important knight of Arthur coming from Gaul, has been analyzed as “Alan-s-Lot” which means “the Alan of Lot” (a river of Gaul). The majority of Arthur’s friends and enemies (Merlin, Morgana, Bors, Mordred etc.) have personal names of Celtic etymology, eg the name Morgana is the female equivalent of Morgos or Morgol, an ancient Celtic wizard-god. But specifically the names Percival(Parsifal) and Balin (Arthur’s companions) have satisfactory Iranian etymologies. The Sarmatian language was Iranian. According to another theory, the name “Balin” comes from a phonetic corruption of the national name of the Alans (B-Alan). Furthermore, Balin’s brother was called Balan.

Sarmatian warrior clad in scale armor. Fluttering behind him is the distinctive Iranian battle standard, a dragon made like a windsock. Fragments of a funeral stele from the Roman camp at Chester, England. Chester Museum. Photo: Chester Archaeological Society. From The Sarmatians (New York, 1970), pl. 46.

The proponents of the Sarmatian theory on the origins of the Arthur’s Epic Cycle, attach its origins in a distant saga of the Sarmatians which they “transplanted” in Britain. Judging by the nomads of the medieval and modern times, it is certain that the Scythians, Sarmatians, Huns and other nomadic peoples had a highly developed epic tradition. The great Western European epics (the Epic Cycles of Nibelungen, Dietrich, Arthur etc.) were based on the lives of heroes of the 5th century AD, the exact period of high dispersion of Sarmatian and Hunno-Sarmatian tribes in western Europe. From the same nomadic saga source probably comes the German epic poem Waltharious, the English Parsifal (Perceval, Parzival) and the Anglo-French Sir Balin. The last two heroes originally had their own epic poems which later were integrated together with their heroes into the Arthurian Epic Cycle.

The same applies to other heroes or knights of the same Cycle, who are originating from the epics of other peoples. For example, Tristan, a well-known knight of the Round Table, comes from the integration of the Pictish epic of Dunstan in the Arthurian Epic Cycle. Dunstan was an historical person, a hero of the Caledonian Picts, who managed to check temporarily the Scots who had invaded his country (coming from Ireland). But the Scots finally conquered Pictland, thus establishing Scotland. Dunstan was a Northern British ‘equivalent’ of Arthur. It should be emphasized that Parsifal and Balin are the only heroes of the Arthurian Cycle whose names have Iranian etymology. Additionally, a medieval chronicle mentions that Parsifal was Lancelot’s son (and therefore brother of Galahad) who has an Alanic name as we have seen.

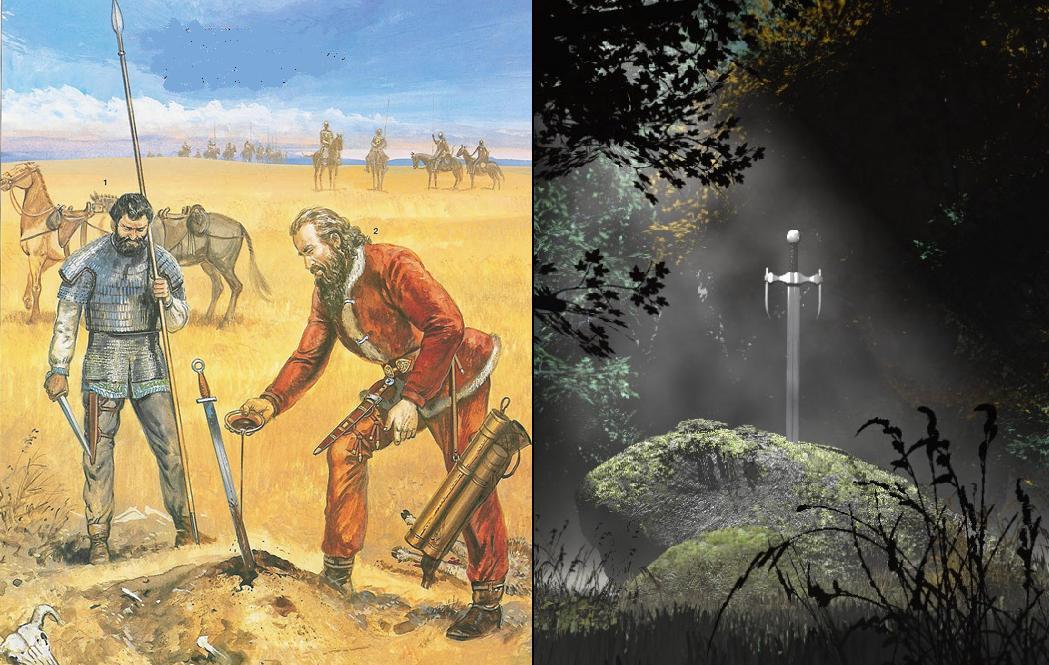

The aforementioned hero Waltharious is described in his epic as being armed “in the way of the Pannonians‘, i.e. bearing two swords. The oldest populations of Pannonia were mixed Northern Illyrian, Celtic and Iranian (Cimmerian and Scythian). During the Early Medieval Great Migration of Peoples, the country had a Sarmatian ethnic majority. We have seen that Pannonia was the homeland of the Iazyges of Britain. It is probable that the arming “in the way of the Pannonians’, with two swords, was a typical Sarmatian habit. Indeed, archaeologists are discovering in the Sarmatian tombs, gold plates almost always in pairs, which come from sword-sheaths. This evidence confirms that the Sarmatian warrior carried two swords. The important thing is that Parsifal and Sir Balin are described as also bearing two swords each. After Balin’s death, one of his swords is nailed to a marble or a rock by Merlin. We shall see that the medieval references of swords that are nailed to earth or rock, are directly related to the Sarmatian religion.

Additionally, Parsifal and Balin are heroes associated with the search of the Holy Grail. The presence of the Holy Grail Legend in the Arthurian Cycle, is usually considered to be related to the sacred pots and sacred boilers and craters of the ancient Celtic religion. This scenario is very likely. Nevertheless, the Sakas (ancestors of the Sarmatians) and their Scythian brethren, as evidenced by their tombs, used special ceremonial craters and boilers to burn opium on hot stones at their rites and inhale the smoke “screaming of joy” as the Greek Herodotus describes in his History.

These Iranian-Sarmatian elements of the figures of Parsifal and Balin enhances the likelihood of the Sarmatian origin of their ‘personal’ Epics, as well as the same origin of the general Legend of Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table. The Hungarian epic Anna Molnar and the Turkish Targhyn have certainly the same nomadic origins. The name of the hero Targhyn has the same etymology as the aforementioned “Pendragon” of the Arthurian Cycle.

Arthur’s legend mentions the existence of two “magical swords”. The one was the sword of Uther, Arthur’s father, which was nailed to a rock. Arthur was proclaimed king when he dragged it off the cliff, while the other candidates for the throne had failed. It is characteristic that the Sarmatians worshiped their main deity in the form of a sword nailed to earth or rock. The second “magic sword” of the legend is the famous Excalibur, which Arthur received from the “Lady of the Lake”.

(left) A reconstruction by Brzezinski and Mielczarek (2002) of Iranian-speaking Sarmatian warriors paying their respects to a fallen comrade in Europe (circa 1st century CE) – note the ritual of thrusting the fallen comrade’s sword into the earth. At right is a screenshot of the Excalibur sword of King Arthur thrust into the stone (Movie “Excalibur“, 1981, John Boorman). This is one of many parallels between the Arthurian legends and the mythologies of the ancient Iranians (Pictures used in Kaveh Farrokh’’s lectures at the University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division).

The episode of Excalibur is almost identical to the reports of ‘magic swords’ in the saga of Batradz, a hero of the Ossetians of the Caucasus, and also in the episode of Krabat’s death which is included in a popular history of the modern Sorbs of Eastern Germany. The modern Ossetians are the last surviving Sarmatians, being descendants of Alans. They are divided among the Russian Federation and Georgia (Autonomous Republics of Northern and Southern Ossetia respectively). The Sorbs, a people of a few tens of thousands which is surrounded by millions of Germans, are Slavs but they bear a Sarmatian tribal name. The same applies to the Serbs of Serbia and other former Yugoslavian republics, brethren of the Sorbs of Germany. The Serbs/Sorbs and the Chrovates (Croats) were originally Sarmatian tribes which became the leaders of many hitherto unorganized Slavs, whom they enrolled in their tribal ‘federations’ (unions). Their population were much less than the population of their Slavic ‘partners’, therefore they were Slavicized and formed the “State ancestors” of the modern Serbs and Croats. The northern branch of the Sarmatian Serbs/Sorbs lived in the Slavic Lusatia (in modern East Germany), leading their Slavic vassals. The Germans conquered (reconquered in reality this ancestral Germanic/Teutonic land) and Germanized the Sorbian territory during the Late Middle Ages, therefore only a few tens of thousands of Sorbs are left in the 21th century in this “Northern Serbia”. The Sorbs retained the epic poems of their old Sarmatian aristocracy, among them the saga of Krabat’s death.

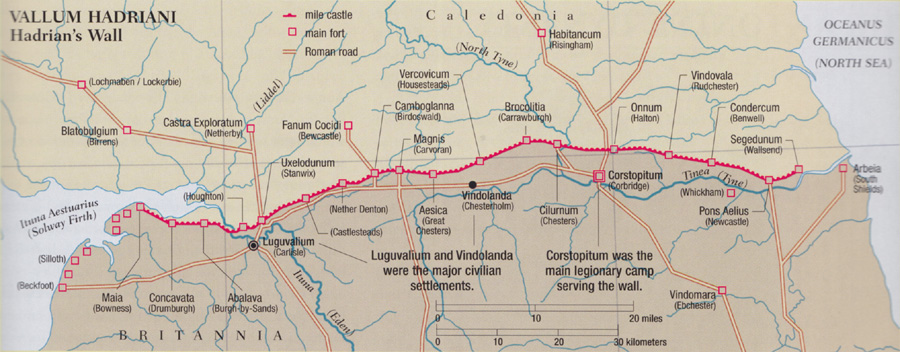

According to Geoffrey, Arthur halted the Anglo-Saxon invasion. Nennius mentions that he made it by giving twelve victorious battles against them. Archaeology confirms the repel of the barbarians who did not conquer any new Briton territories for more than 50 years. German archaeologists also found that a number of disappointed Anglo-Saxons returned to their homelands where they refounded their villages. However, the battles that Arthur gave, are often identified by scholars in locations covering almost the entire Great Britain. Some researchers question the validity of Nennius’ reference, because they believe that Arthur could not move his army as rapidly as was necessary in such large distances. Those researchers are probably wrong. It is almost certain that the core of the army consisted of cavalrymen and horsemen. The Sarmato-British cavalry of the Arthurian period was not as heavily armored as the primeval Sarmatian because its horses were unarmored. There were no cataphracts in that period, only heavy cavalry. But the Sarmato-Briton cavalry could cover large distances in high speed in order to reach any place of the former Britannia where the Germanic, Irish or Pict raiders appeared suddenly, and fight them. Moreover, Arthur or the Duke or king that he represents, could move quickly his infantry as well, taking advantage of the excellent Roman roads of Britain. Although the Roman administration had left since the early 5th cent., the roads remained in a good condition and they consisted an important military advantage of the Britons against their enemies, because the natives knew very well these roads. They could also ambush the invaders. After all, the Romans had constructed those roads mainly for military use.

Romano-Britons (on the left) confront Anglo-Saxon invaders in a reenactment by the Historical Association Britannia (Source: Periklis Deligiannis).

Arthur, abandoned by many British warlords who envied his power, was killed according to tradition in the battle of Camlann (537 or 539 AD). Soon afterwards, the Celts faced new hardships. The new pestilence which had occurred in the Mediterranean around 542/543 and killed nearly half the population of Constantinople, reached the island through maritime trade. The Britons had more victims than the Saxons, because they used to trade with the Mediterranean countries. On the contrary, they had very limited contacts with the invaders who thus were not exposed to serious infection. The Briton resistance against the barbarians was weakened by Arthur’s death and the plague, and thereby collapsed. A century later, the advancing Anglo-Saxons had conquered practically the whole of modern England (except Cornwall and Cumbria/ modern Cumberland).

By inference, it is difficult to ascertain the relationship between the Sarmatians of Britain and the Arthurian Epic Cycle. It is very likely that the medieval British gave legendary dimensions to the deeds of the descendants of the Sarmatian cavalrymen who for four centuries had defended their country, and in this way the Arthurian Legend was born. Arthur was not a Sarmatian but he was possibly a descendant of the Roman officer Artorius Castus or a bearer of his name as a title (like Caesar). The victories of the Sarmatians in the island became legendary because of their thrusting warfare, which differed radically from the Briton warfare of that era (depending almost exclusively on infantry), and because of its impressive results against the barbarians. After all, the Empire used to hire the Sarmatian mercenaries exactly for those military qualities. In any case, it is certain that the Sarmatians and their descendants have played a fundamental role in the defense of Roman and Sub-Roman Britain.

Bibliography – Further Reading

- Nennius: HISTORIA BRITONNUM.

- Gildas: “THE RUIN OF BRITAIN” AND OTHER WORKS, Edited and translated by M.Winterbottom, London, 1978.

- Arrian: ORDER OF BATTLE AGAINST THE ALANS.

- Nickel Helmut : FROM THE LAND OF THE SCYTHIANS: Ancient Treasures from the Museums of the U.S.S.R., 3000 B.C – 100 B.C., Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1975.

- Geoffrey Ashe: THE DISCOVERY OF KING ARTHUR, London, 1995.

- J. Harmatta: STUDIES ON THE HISTORY AND LANGUAGE OF THE SARMATIANS, Szeged, 1970.

- Tadeusz Sulimirski: THE SARMATIANS, London, 1970.