The article “Scythian Genealogical Legend in «Rustamiada»” written by Igor V. Pyankov (translated into English by T.I.Pyankova) was originally posted in the London-based CAIS (Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies) venue. The version printed below contains images and captions that do not appear in the original CAIS posting.

Readers are also encouraged to consult the following resource links:

==========================================================================

Scythian genealogical legend is told in different versions in classic texts completely and also by separate extracts (the most detailed analysis of all these texts could be found in the works of A.Christensen2, G.Dumézil3, A.M.Khazanov4, and D.S.Raevsky5).

Talking about different plots of ancient Iranian and ancient Indian epic traditions parallel to this legend, specialists don’t concentrate too much on the legend about Rustam, who is the main subject of the Sistan cycle legends. And Rustam is Saka by birth (“Sagzî” of epos), he is Central Asiatic Scythian. In the legend about Rustam there must be more close connection to Scythian epos. According to Curtius Rufus (VII, 8,17,18) Scythian genealogical legend was also known by Central Asiatic Scythians. Legends about Rustam together with Sistan cycle were told in detail in «Shahname» by Firdausi. So, further, talking about the legends of Rustam we will mainly apply to the work «Shahname» to find parallels to Scythian genealogical legend.6 And intermediate stage between Scythian genealogical legend and legends about Rustam of the latest Iranian epos is Sogdian version of legends about Rustam and of what we will talk further on. And these legends were very popular with the Sogdians, as we know this from Sogdian literature and from the fine arts, where is the most expressive thing – the Penjikent murals.

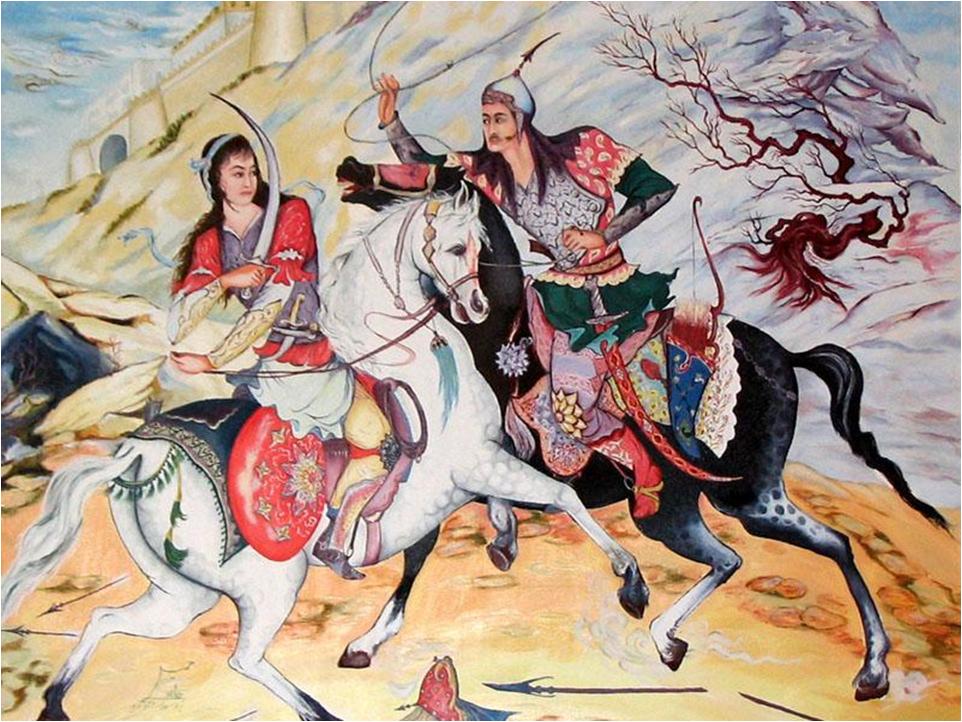

Rustam, accompanied by his horse Rakhsh, slays the dragon (Source: Merovingians: The Once, The Present, & Future kings on Facebook). The tales of Rustam (the “Hercules of Persia”) are narrated in the Shahname epic written in the post-Islamic era after the fall of the Sassanian Empire. Known as the “Illiad of Persia”, the Shahname has preserved much of Iran’s ancient pre-Islamic heritage.

Herodotus told one of the most complete versions of Scythian genealogical legend in his story about “Scythian Heracles” (IV, 8-10). And Herodotus’ story is expanded by information of other ancient authors. So, Herodotus tells: Once Heracles, driving his bulls in front of him, came to the deserted country at the Pontus’ shore (the Black Sea), country which later was inhabited by the Scythians. The snow-storm was raging, it became cold, Heracles wrapped himself in lion-skin and went to sleep leaving his horses in the pasture. Getting up, he found out that by some miracle his horses disappeared and he left the place for searching them. In the cave, which was in the forest, he met a wonderful creature-maiden: the lower part of her body had the form of snake. This maiden-echidna introduced herself as the master of the deserted country and promised to give him his horses back on condition that Heracles should have intimate relations with her. Heracles agreed to do a deal with her and the maiden did her best to keep him by herself as long as possible. Only later when she understood that she would have three sons from Heracles, she let him go, gave him back horses and got from the future father gifts which were meant for the most worthy son. And this worthy son was turned out to be Scythes, descendants of whom inhabited that country which had been deserted before.

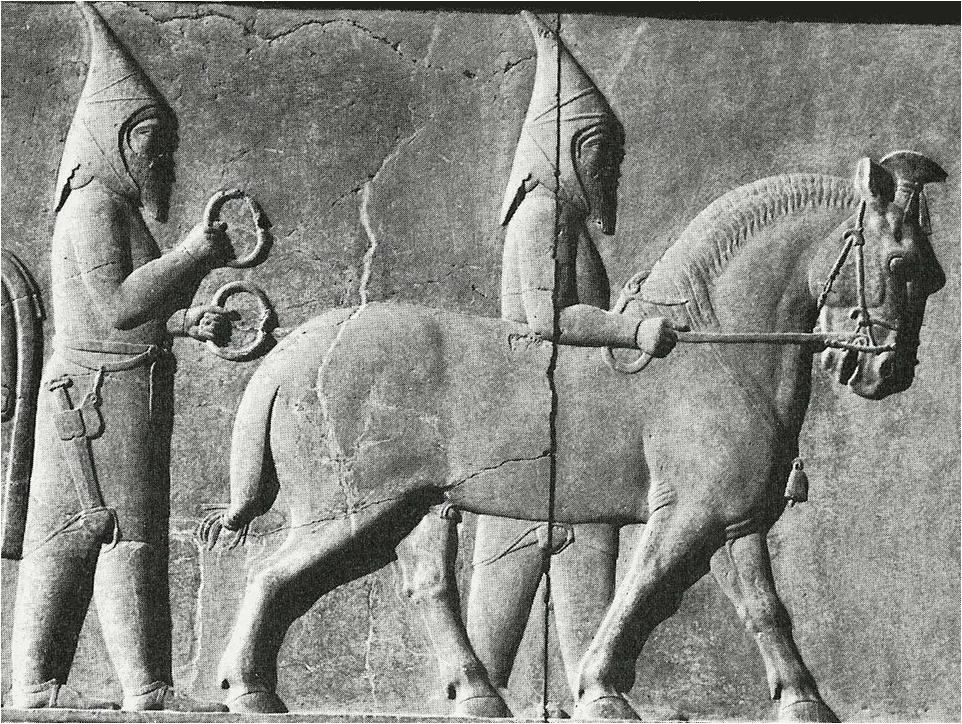

Eastern Scythians or “Saka Tigrakhauda” (Pointed cap Saka) as depicted in Persepolis. The Scythians played an important role in the military machine of the Achaemenids. A branch of the Scythians or Saka, the Parthians, were to revive the Iranian kingdom after Alexander’s conquests and his Seleucid successors.

Herodotus called this legend Hellenic, but actually it is the local Scythian legend which has only Hellenic editing . Scientists have been interested in this legend for a long time, and they are sure that it is one of the versions of the Scythian genealogical legend, legend which explains the origin of the Scythians. In this legend we see the Scythian hero, known by the Greeks as Heracles, and the ancestors of the Scythians, according to this legend, were the Scythian hero and the mythical creature. That mythical creature was the outcome of the Earth and the Water, who was known as the daughter of the main river of that people, whose origin we know from the legend.

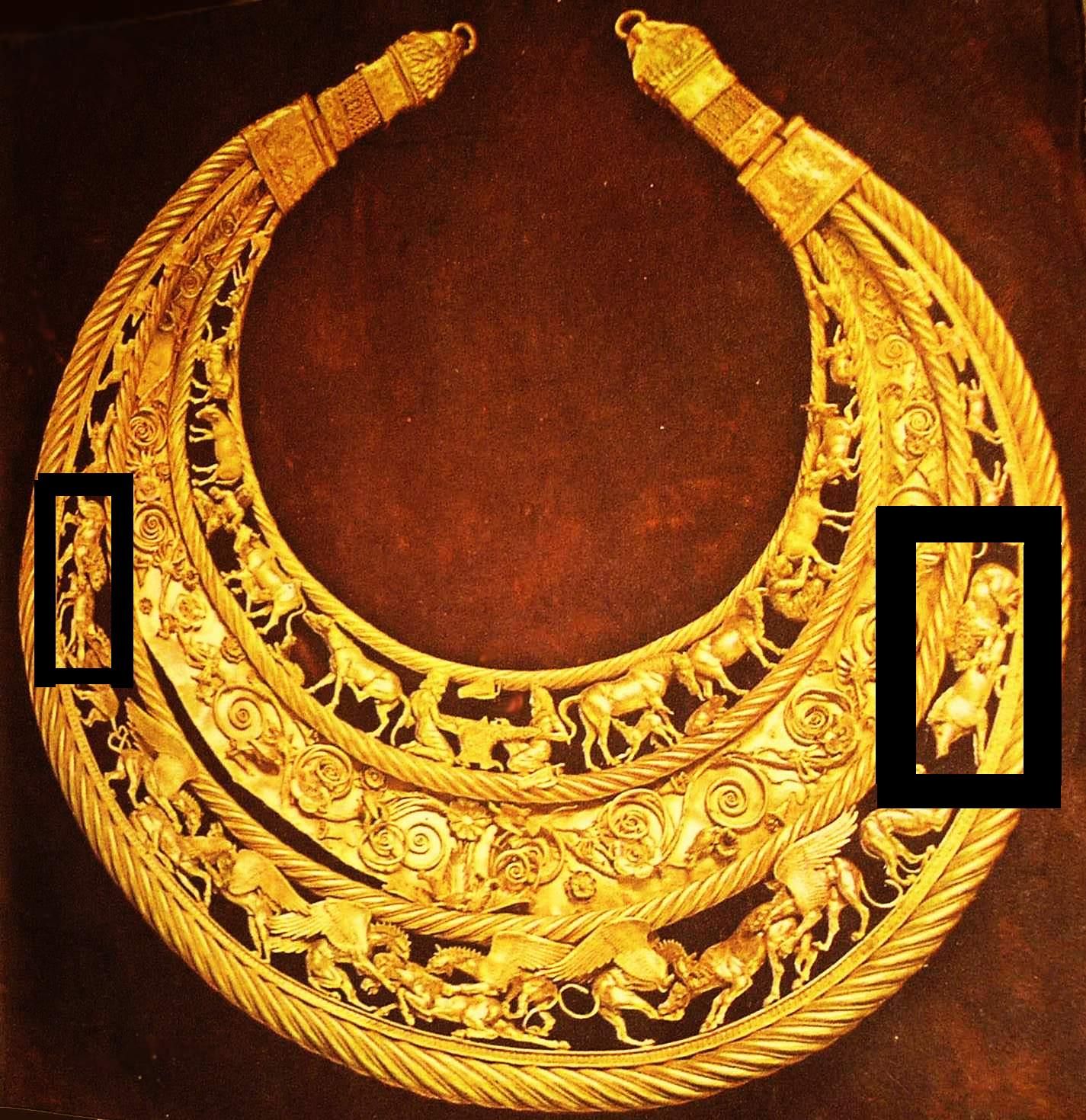

Golden necklance or pectoral of an ancient Iranian queen in what is now North Ossetia. The areas shown with black rectangles depict lions attacking their prey – these are virtually identical to those seen in the Apadana stairway at Persepolis.

Can we find in the most ancient layers of «Rustamiada» similar plots? Yes, we can. And we’ll try to show it. Also we should take into account that the initial genealogical meaning of this myth was forgotten not only in Firdausi times, but during the times of its origin too. Certainly, Rustam could not appear in the epos as the ancestor of the Sakas, and also the Sakas themselves were forgotten too, and in that time the myth was just taken as a fairy-tale. The myth was adapted according to the new world outlook and adjusted for the common plot of the poem. But in spite of all, it is really surprising that in Firdausi’s poem some parts of the ancient myth were carefully preserved, and this fact gives us opportunity vividly see the myth in «Rustamiada». In «Rustamiada» we can find two plots which preserved the echos of the Scythian (or Sakian) genealogical legend.

Persian miniature depicting female warrior Gordafarid locked in a duel with Sohrab, the son of the ancient Iranian hero, Rustam (Source: I Make Up Worlds).

In one of the plots we can notice a primitive naturalness and archaism of the myth in its original appearance. This is a story about Rustam’s battle against dragon. In Firdausi’s poem this story was included into the legend about “seven camps” of Rustam, or about his seven feats which he performed on the way to Mazandaran (Vol.I. Lines 11597-12356). Poet tells us: Rustam is riding his faithful horse Rahsh and sees in front of him the herd of onagers, he is hunting the herd, catches one of the onagers, makes a feast and then goes to sleep in the thicket (Vol.I. Lines 11599-11620). In this story we see onagers instead of bulls, but actually the beginning of the story is quite suitable to continue this narration about the main adventure of the hero in the spirit of Herodotus. But Firdausi interrupted his narration to include into it two additional episodes. First episode: the victory over the ferocious lion (Vol.I. Lines 11621-11650) (and it becomes clear why the Scythian hero has lion-skin). Second episode: the discovery of the spring; near Rustam, who was feeling thirsty in the burning desert, appeared a miraculous roe-deer who leads him to the invigorating moisture of brook (Vol.I. Lines 11651-11728). Here it is used an alternative version of myth about the ancestor: the magic fallow-deer with golden antlers leads the ancestor to the river, to the place of his people future living. The fact, that this plot was included into the series of stories about Scythian Heracles, means that the Scythians knew this plot. According to one of the versions, told not by Herodotus but by other authors (Pindar, Ol. III, 30-33), Heracles, hunting Kerinean fallow-deer, visited Scythia as well. And in general, according to the sources by the classical authors, the legend about magic golden antlers fallow-deer was widely spread in the genealogical legends of different Scythian peoples. Taking into account the late transformation of the myth, it becomes clear also why the country, in which Rustam appeared, wasn’t only the lonely place, but the real sandy desert, where the main character suffered not because of the frost, but because of intense heat and lack of water.

A portion of the Pazyryk carpet found in Central Asia dated to 2,500 years ago. Known as the first known Persian carpet, note the depictions of mythical (winged) lions on the bottom panels. Of interest are the “X” type symbols along the top panels. These were to become a central motif in the major standard of Partho-Sassanian Iran: the Drafsh e Kaviani or the Standard of Kaveh. For more on this topic see … The Lion and Sun Motif of Iran: A brief Analysis …

Having described these two episodes, Firdausi as if comes back to the former plot. Rustam, after he had had enough onager’s meat, covered himself with the animal’s skins and fell into sleep at the brook. But at night a terrible dragon appeared three times in front of his horse Rahsh, dragon who lived in the nearest growth. Two times the dragon disappeared, worrying the horse, but for the third time dragon had to fight with Rustam. During the battle the dragon declared himself as the master of the whole desert (Vol.I. Lines 11729-11832). So, we see that the main moments of the stealing Heracles’ horses by maiden-echidna were preserved in this story: the dragon tried to attack only Rahsh but then disappeared. Also such detail as lion-skin, in which Heracles wrapped, falling into sleep, was also preserved. Though in the poem it is told about “skin-shell (of big feline beast of prey)” (babr-e beyan), the previous episode with lion vividly shows us, that the raiment, the main character had, was made from the lion-skin. We can notice the original nature of dragon in connection him with growth and brook, even if there are no direct indications that it was half snake half woman. Also there is no any love-theme in this legend. But right after the description about Rustam’s battle against dragon, Firdausi tells us about some sorceress who tried to seduce Rustam. The place of adventure was again near the brook in the shade of the trees where there was a dastarhan full of different viands (Vol.I. Lines 11833-11892). And again if we remember maiden-echidna, she tried to keep by herself Heracles as long as she could showing him her hospitality.

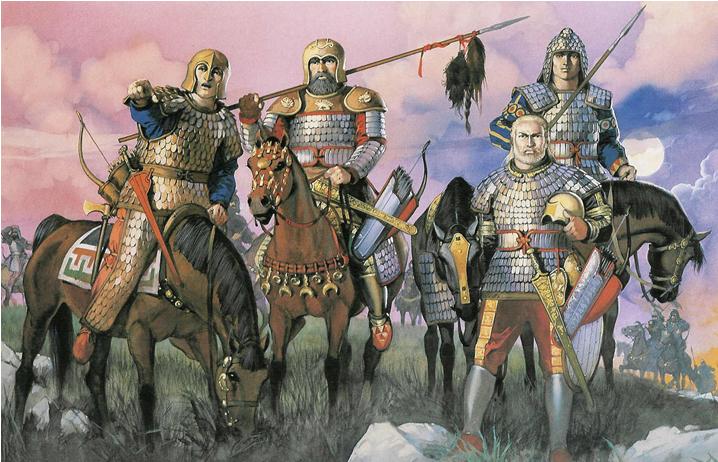

A reconstruction of the European Scythians (the Saka Paradraya) by the late Angus McBride. As noted by Cotterell “:..the close relations of the Scythians (Saka) with the Persians is perhaps most illustrative…in the … fact that the Scythians and Persians spoke closely related languages and understood each other without translators” (Cotterell, A. The Chariot: The Astounding Rise and Fall of the World’s First War Machine. London, England: Pimlico, 2004, p.61).

Fortunately, we can compare Firdausi’s story about the meeting between Rustam and the dragon with more early version of the same story which was shown with the help of murals in the ancient Penjikent. On that frescoes we can see Rustam’s battle against the dragon. A lot of details, which have direct correspondence to the text of «Shahname», can be found in the frescoes: dragon with its serpentine body entangles horse’s legs, the rider takes his sword, strikes dragon by it, the dragon is defeated and his blood floods everything around.7 And here it is shown just the battle of the main character against dragon, but the genealogical meaning of myth was forgotten, the same as in Firdousi’s poem. However, there is an important detail in the frescoes: the upper part of dragon’s body has woman look, the same as in Herodotus’ story, where it is a maiden-echidna, and attacking the horse dragon tries to embrace the rider. So, we can notice that according to the murals’ version the love theme existed together with the battle against dragon, unlike Firdousi’s version.

Sarmatian-Alan warriors engage in ancient rituals in the burial of a late comrade. An important ritual was the thrusting of the sword into the earth, a tradition still found in surviving ancient cults in parts of western Iran. The sword was a potent theological symbol in ancient Iranian rites. The above reconstruction is also of interest in that it shows that lamb sacrifice and the spilling of blood have pre-existed among Iranian peoples before the arrival of Islam into Sassanian Persia, Anatolia or the Caucasus (Brzezinski & Mielczarek, 2002, Plate B). Elements of the North Iranian legends have survived in the Shahname.

In the second of those two plots, had been mentioned before, the initial myth was completely rationalized and given as a nice love-story, answering the most exquisite literary tastes in the days of Firdausi. But the main plot line of this story, actually, remains the same as it was in the first case. It is a story about Rustam and Tahmīnah, which is the component part of the famous legend about Suhrāb. And here we again see Rustam hunting onagers on the plain but this time on the way to Turan. Again Rustam caught an onager, made a feast and fell asleep in the growth near the water, meanwhile his horse Rahsh was pasturing on the grassland. And here Rustam’s skin-shell was again mentioned. But this time the horse was stolen by the Turans, according to the common rationalization of the plot. So, Rustam set off for searching his horse Rahsh. Horse’s traces led Rustam to Semengan. That was a real city, well-known in the Middle Ages, situated in the valley of the river Hulm to the south from Amu Darya. The king of Semengan with his suite met Rustam. Rustam, threatening king, demanded to return his disappearing horse, but king treated him respectfully, called him the sovereign and gave a feast in his honour. During the night king’s daughter Tahmīnah came to Rustam, she was consumed with passion to him, promised him to return his horse and declared her wish to have son from him. Rustam married Tahmīnah and gave her an amulet for the future offspring after what he went away with his horse Rahsh. (Vol.II. Lines 37-266).

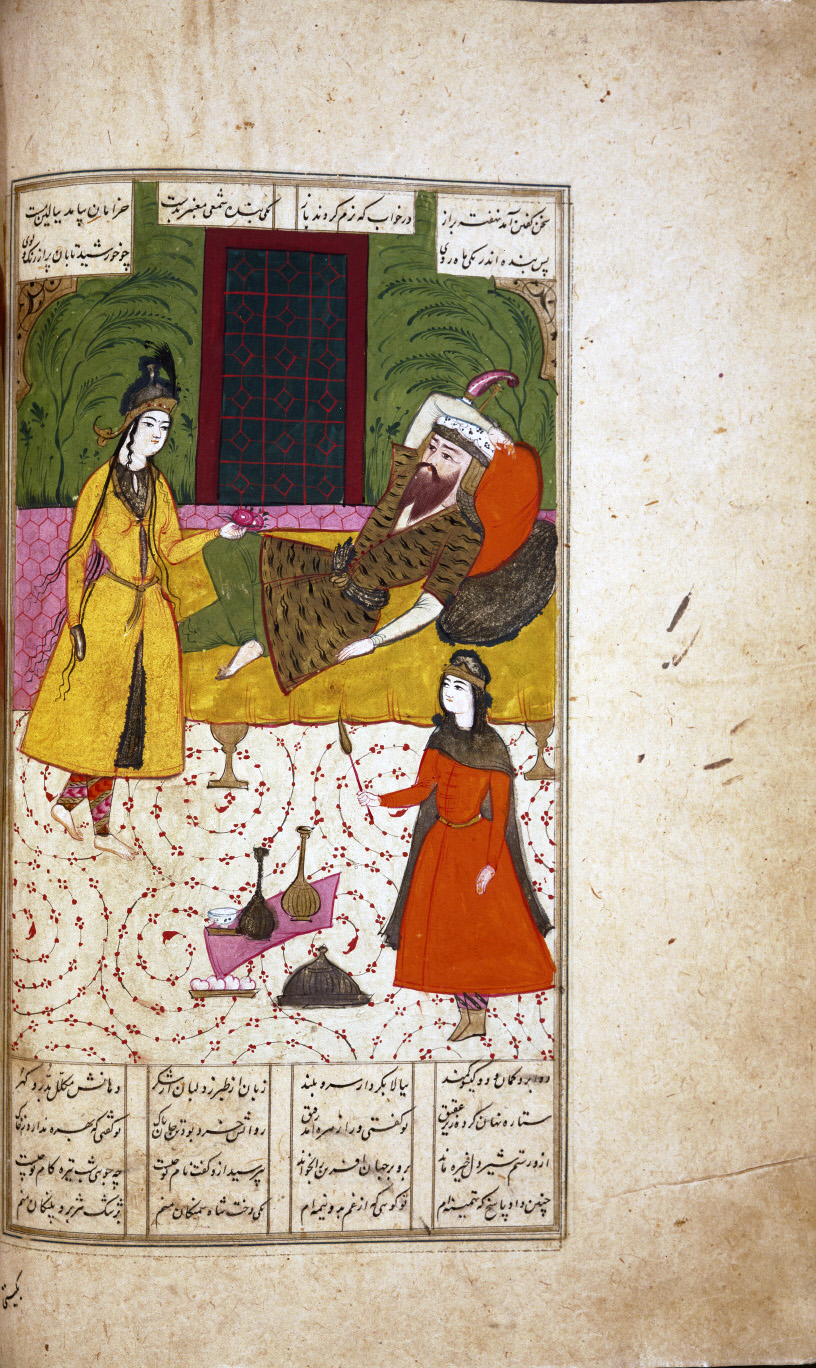

Persian manuscript from a Shahname drafted in 1674 depicting Tahminah visiting Rustam; housed at the Princeton University Library (MS 58 G) (Source: Public Domain).

As we see the plot here, in main, is the same as in the Scythian legend.8 But there are no supernatural elements and fairy-tale in this story. In the image of beautiful Tahmīnah there is nothing what could remind us about the primitive dragon, and in general, situation itself and all details are rather realistic. Though in the plot there appeared a new character – Tahmīna’s father, the king of Semengan, and for this character we can find the correspondence in the series of legend about Scythian Heracles. According to one of the versions of the Scythian legend, not used by Herodotus, Heracles, after he had come to Skythia and defeated Araxes, had intimate relations with his daughter Echidna (Inscriptiones Graecae, XIV, N°1293A, 94-97).9 Here Araxes is the divinity and personification of the river, which in some versions of the Scythian legend was shown as the river of the homeland of the Scythians.

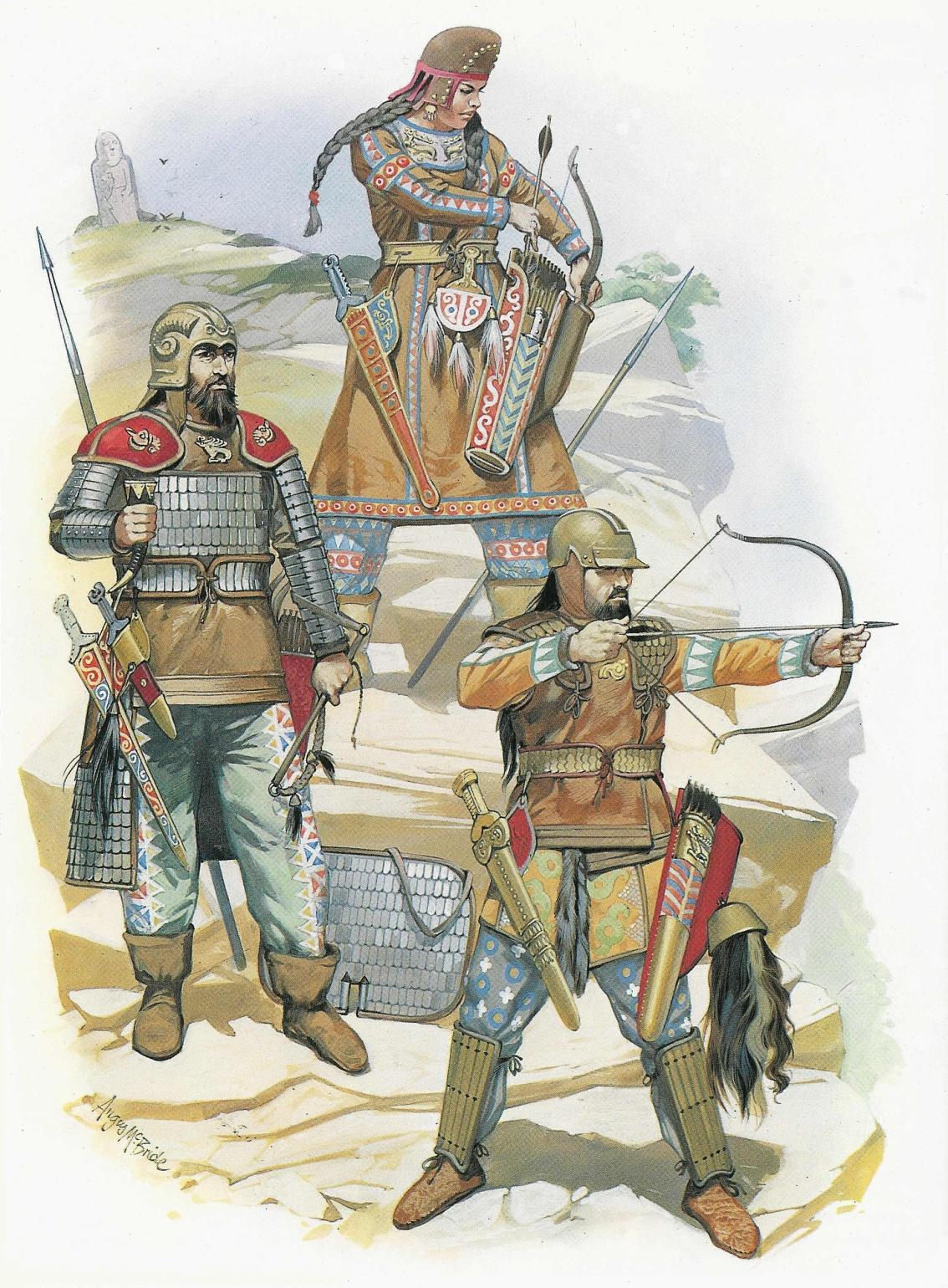

A reconstruction by Cernenko and Gorelik of the north-Iranian Saka or Scythians in battle (Cernenko & Gorelik, 1989, Plate F). The ancient Iranians (those in ancient Persia and the ones in ancient Eastern Europe) often had women warriors and chieftains. This practice was not unlike those of the Scythians’ contemporaries to their west: the ancient Celts of Central and Western Europe. What is also notable is the attire of the Iranian female warrior – this type of dress continues to appear in parts of Luristan in Western Iran (for more on this topic see – Fezana article on Ancient Iranian Women).

We should note that the story about Rustam and Tahmīnah, unlike the story about Rustam’s battle with dragon, preserved the original genealogical meaning of the myth: Suhrab was born by Tahmīnah, and he was the son of Rustam. And it is interesting fact, that in Firdausi’s story some details, limited by that genealogical meaning, were preserved, though the content of myth was changed. In the Scythian genealogical legend the progenitress had three sons and for each of them there was a gift given by their progenitor. The gifts themselves were described in different versions in different way, but the common factor is that all of them were made from gold. And in Firdausi’s story Tahmīnah had only one son – Suhrāb, but Rustam sent him as a gift three sacks full of gold (Vol.II. Lines 297-304).

The Pazyryk carpet displays the first depiction of the Drafsh-e-Kaviani. The Pazyryk region was settled by North Iranian Scythian peoples. It is possible that the Parthians, who were of Scythian stock, introduced this ancient Iranian theme as Iran`s major standard. For more on this topic see … The Lion and Sun Motif of Iran: A brief Analysis …

Scythian genealogical legend shows us a number of other correspondences in the stories of Sistan epic cycle. So, according to the legend, the progenitor of the Scythians gave birth to three sons, who in some versions of the legend are considered to be founders of three peoples, and in other versions of the legend those sons are considered to be the ancestors of three estates, or three “castes”. Each caste had its own colour: priest – white colour, military – red colour. It is known other version of the legend, also not shown in Herodotus’ story but just makes an addition to this story, so the version where the founder of the priest caste is characterized as an elderly man with white hair from birth; and to the founder of military caste the emblem, having the form of three lights and resembling the shafts of lightning, was attributed (Valerius Flaccus, VI, 48-68).10 As we can notice, the story about Rustam and Tahmīnah has a hint that initially there was a talk about three Rustam’s sons. Though this theme about three sons and successors of the progenitor became obsolete in Sistan cycle, it remained very significant traces. One of these traces – strange, at first sight, name of Rustam’s father Zāl-i Zar ( «White-Haired Old Man») and the legend about him, being white from birth. Another trace – the name of Rustam’s son Suhrāb (or Surkhāb, «Having the Red Glitter»).11

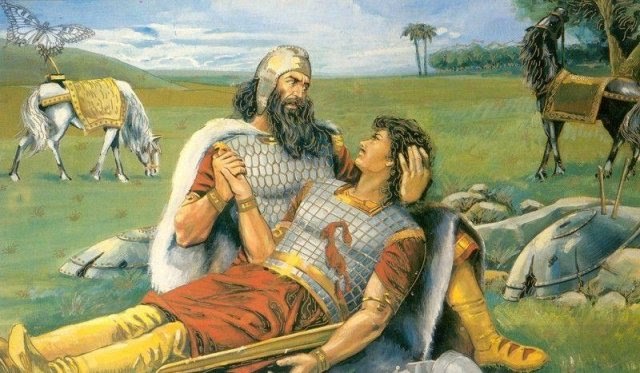

Rustam holding his dying son, Sohrab, in his arms (Source: Amir el Mander in Public Domain).

Though the image of Rustam in «Shahname» by Firdausi drew in itself features of some historical personalities – representatives of Sakastanian ruling family of the Surenas, – but the basis of the image goes from the remote Scythian (Sakian) history and mythology. Rustam’s image appeared there as the progenitor of the Scythians (of the Sakas). He had took up with the river-divinity after what he had his descendants and also the river-divinity let his horses pasture on grasslands of this river. And it is important to note that the remote Scythians’ ancestors, cattle-breeders and horse-breeders, who settled in vast territories of Eurasian steppes and created such a myth, were close to the reality, because the waters of the steppe rivers and thick grasslands really gave them, their descendants and their herds the possibility to live.

So, the Scythian genealogical myth is just a version of the same generally Iranian and even generally Indo-Iranian myth. Its various samples we can find in « Shahname» (legend about Faridun and his sons), in «Avesta», and in «Rigveda». Traces of the Scythian genealogical legend are still preserved in folklore of that area, where in former times the Scythian peoples lived. In the territory of the Southern Tadjikistan in 1965 I heard the stories from local inhabitants about some dangerous maiden-echidna who lived in the river. Those stories vividly reminded me of Herodotus’ story about the Scythian Heracles.

Bibliography

Belenitsky A.M. (1967). Drevniy Penjikent – rannefeodalny gorod Sredney Azii. Leningrad, 1967.

Belenitsky A.M., Stavisky B.Ya. (1959). Novoe o drevnem Penjikente. // Arkheologi rasskazyvayut. Stalinabad, 1959. S. 38-66.

Christensen A. (1918). Le premier homme et le premier roi dans l’histoire légendaire des Iraniens. 1. Uppsala, 1918.

Dumézil G. (1941). Jupiter, Mars, Quirinus. Paris, 1941.

Grantovsky E.A. (1960). Indo-iranskie kasty u skifov. Moscow, 1960.

Justi F. (1895). Iranisches Namensbuch. Marburg, 1895.

Khazanov A.M. (1975). Sotsialnaya istoriya skifov. Moscow, 1975.

Pyankov I.V. (1985). Skifskaya genealogicheskaya legenda v “Rostemiade”. // Tvorcheskoye naslediye narodov Sredney Azii v pamiatnikach iskusstva, arkhitektury i arkheologii. Tashkent, 1985. S. 103-105.

Pyankov I.V. (1992). Rustam – geroy “Knigi tsarey”: skazka ili byl? // Pamir. 7-8. Dushanbe, 1992.

Raevsky D.S. (1977). Ocherki ideologii skifo-sakskich plemion. Moscow, 1977.

Tolstov S.P. (1948). Drevniy Khorezm. Moscow, 1948.

Tolstoy I.I. (1966). Statyi o folklore. Moscow – Leningrad, 1966.

Notes

*Doctor of History. Universal History Professor. Yaroslav the Wise State University of Novgorod the Great, Department of History

1 I’ve already applied to this theme in my works in Russian language: Pyankov (1985), S.103-105; Pyankov (1992), S.145.

2 Christensen (1918), P.136-139.

3 Dumézil (1941), P.49-57, 220-225.

4 Khazanov (1975), S.36-54.

5 Raevsky (1977), S.19-86.

6 The quotations from this work are taken from the publication: Firdousi. Shahname. Vol. I,II. Moscow, 1957, 1960.

7 Interpretation these murals as is there are scenes from the legend about Rustam was proposed by A.M.Belenitsky: Belenitsky, Stavisky (1959), S. 62-66; Belenitsky (1967), S. 23.

8 This similarity had been already marked: Tolstov (1948), S. 294, 295; Raevsky (1977), S. 33.

9 The interpretation of this text is in: Tolstoy (1966), S. 234,235.

10 All these moments of the Scythian genealogical legend are convincingly analysed by E.A.Grantovsky: Grantovsky (1960), S. 5,6.

11 The etymology of these names is in: Justi (1895), S. 313, 378.