The article “Macrinus and Diadumenianus” was originally posted in the Italian Tribune. The Famous and Infamous Rulers of Rome. The version below has been edited. Kindly note that a number of pictures and accompanying captions do not appear in the original version by the Italian Tribune.

=====================================================================

The history of the Roman Empire is perhaps unprecedented in its prosperity, with a stable economy, strong government and superb military. The men who ruled this empire varied greatly, from noble leaders like Antoninus Pius to oppressive despots like Caligula. The story of Rome’s rulers has it all – love, murder and revenge, fear and greed, envy and pride. Their history is a roller coaster that lurches from peace and prosperity to terror and tyranny. This article focuses on Macrinus and his son Diadumenianus, who took the throne when he was only ten years old.

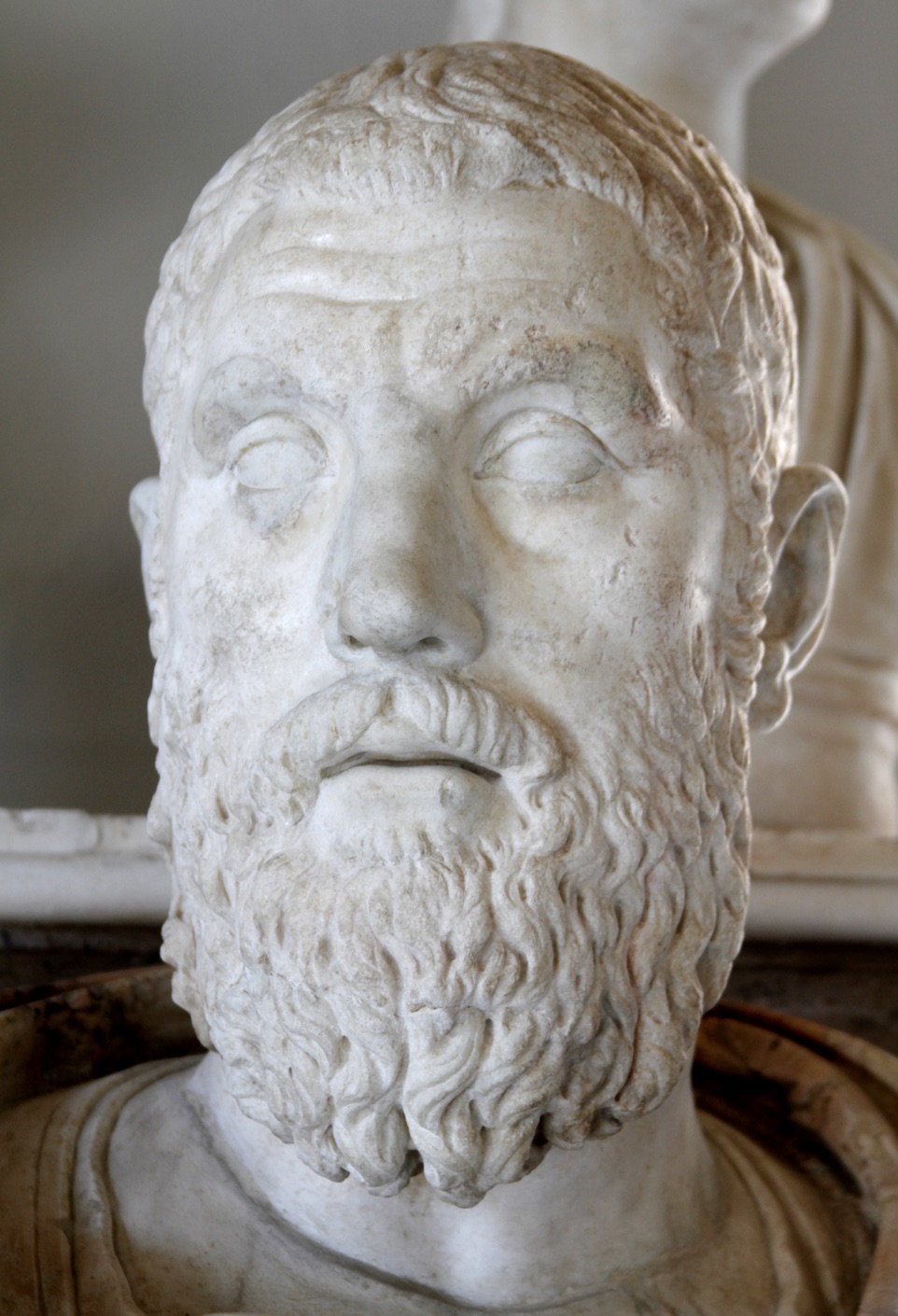

A Roman aureus of Macrinus with the reverse side showing Macrinus with his son Diadumenianus (Source: Classical Numismatic Group Marcus Opellius Macrinus was the first emperor who was neither a senator nor of a senatorial family at the time of his accession. His 14-month reign was spent entirely in the East, where he proved unable to maintain the influence gained in the region by the campaigns of his predecessor, Caracalla, nor was Macrinus able to shake the suspicion that he was responsible for Caracalla’s murder. Bust of Marcus Opellius Severus Macrinus Augustus at the Palazzo Nuovo, Musei Capitolini in Rome (Source: José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro in Public Domain). Macrinus’ reign was ephemeral, having ruled for just a year in 217-218 CE Growing up Macrinus, born in 165, received a literary education that enabled him to rise high as a bureaucrat in the imperial service during the reign of the emperor Severus. Caracalla made Macrinus a praetorian prefect, an equestrian post that was second to the emperor in power. Macrinus shared the position with the experienced soldier Adventus, and the pair served Caracalla during the emperor’s campaigns in the East. By the end of the second campaigning season in 216-17, rumors were flying that Macrinus was promoting himself as a possible future emperor. Caracalla must have been aware of the rumors concerning Macrinus, for the historian Cassius Dio notes the emperor was already reassigning members of Macrinus’ staff. Such personnel moves may have accelerated Macrinus’ plot. Shortly before the campaigning season was to begin, Caracalla paid a visit to a temple near Carrhae. The emperor was accompanied by hand-picked bodyguards. The guards returned with Caracalla’s murdered body along with the body of one of the guards and a story that the dead guard killed the dead emperor. Not everyone was convinced, but Macrinus was able to translate his authority as praetorian prefect into that of emperor, being proclaimed by the troops in 217. Macrinus soon named his son, Diadumenianus, as Caesar and heir. The new emperor also got his former colleague, Adventus, out of the way by sending him back to Rome as urban prefect. Macrinus immediately sent conciliatory messages to the Parthian ruler Artabanus V, but Artabanus sensed weakness and raised an army to avenge his losses from the previous year’s campaign. Macrinus hoped to avoid a battle with the Parthians, but fighting erupted between the armies while both sides were encamped around Nisibis. The Parthians gained victory and, during the following winter, peace negotiations were held. Macrinus ended up paying the Parthians large bribes and reparations. Settlements were also reached with the Armenians and with the Dacians, who had launched attacks on the Romans after learning of Caracalla’s death. Parthian cataphract lancers attack the Roman lines during the battle of Nisibis in 217 (Source: Weapons and Warfare). Despite their successes, the camel’s feet proved highly vulnerable Roman caltrops that had been strewn on the battlefield. By not returning to Rome in 217, Macrinus opened himself to criticism. Dissatisfaction was especially high in the city after a particularly violent thunderstorm started a fire that damaged much of the Colosseum and caused widespread flooding, especially in the Forum. Adventus proved himself incompetent as urban prefect and had to be replaced. But grumblings in Rome were insignificant compared to the growing unease among the soldiers on campaign in the East. The defeat at Nisibis at the hands of Artabanus and the Parthian army disheartened the Roman troops. Macrinus also introduced an unpopular, two-tier pay system in which new recruits received less money than veterans. Parthian Horse archers engage the Roman legions as they attempt to invade Persia. Unlike the Achamenid-Greek wars where Achaemenid arrows were unable to penetrate Hellenic shields and armor, Parthian archery was now capable of penetrating Roman armor and shields (Picture Source: Antony Karasulas & Angus McBride). Earlier, Caracalla’s mother, Julia Domna, had toyed with the idea of raising a rebellion against Macrinus shortly after her son’s murder, but the empress was uncertain of success and already suffering from breast cancer. She chose to starve herself to death instead. The grandchildren of her sister, Julia Maesa, would become the focus of the successful uprising that began in 218. Her 14-year-old grandson Avitus (known to history as Elagabalus) was proclaimed emperor by one the legions camped near the family’s hometown. Other troops joined the rebellion, but Macrinus ordered loyal soldiers to crush the revolt, and later promoted his son to the rank of emperor. The forces met in a village outside Antioch in 218. Despite the inexperience of the leaders of the rebel army, Macrinus was defeated. He sent his son, Diadumenianus, with an ambassador to the Parthian king, while Macrinus himself prepared to flee to Rome. Macrinus traveled across Asia Minor disguised as a courier and nearly made it to Europe, but he was captured in Chalcedon. Macrinus was transported to Cappadocia, where he and his son Diadumenianus were executed and Elagabalus was declared emperor. Contemporaries tended to portray Macrinus as a fear-driven impostor who was able to make himself emperor but was incapable of the leadership required by the job. Macrinus lacked the aristocratic connections and personal bravado that might have won him legitimacy. His short reign represented a brief interlude of Parthian success during what would prove the final decade of the Parthian empire.