The article “Pearls of the Taklamakan” was originally posted in the Tang Dynasty Times. Kindly note that the version below contains images and accompanying captions not included in the original Tang Dynasty posting.

================================================================================

Samarkand and Bukhara– the names still evoke images of the great silk road. Part of the vast Persian empire, it was the Central Asian people of Sogdiana who monopolized these ancient trade routes connecting the East with the West. Known in Latin as “Transoxiana,” or “land beyond the Oxus River,” the place was made famous during Alexander the Great Times, during his great exploits East. During Alexander’s times in 4th century BC, Transoxiana was the northeastern-most point of Hellenistic culture.

Tajik girls celebrate the Iranian Nowruz (New Year) on March 21, 2014 in Dushanbe, Tajikestan... for more see “Course on Silk Road-Origins and History”

Populated by Iranian peoples, Transoxiana was incorporated into the Persian Empire first during the Achaemenid Empire. A colonial outpost of the Persian Empire during later Sassanid times, it became known as Sogdiana.

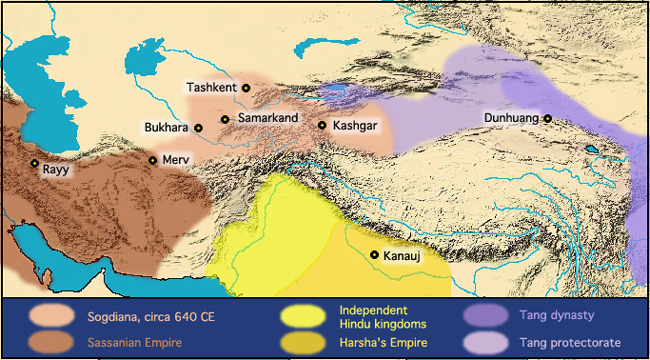

Map depicting Soghdia in the context of the Sassanian Empire, Central Asia and India and China in the mid-7th century CE (Source: All Empires).

With their “contemplative green eyes flashing” and their “purple beards flying in the wind,” the hardy Sogdian traders of Samarkand and Bukhara led caravans on camel-back and horseback over the treacherous mountain passes of the Roof of the World and across the endless stretches of sand of the Taklamakan Desert toward China. And, it was their language, Sogdian, which was the lingua franca of the East during Tang dynasty times.

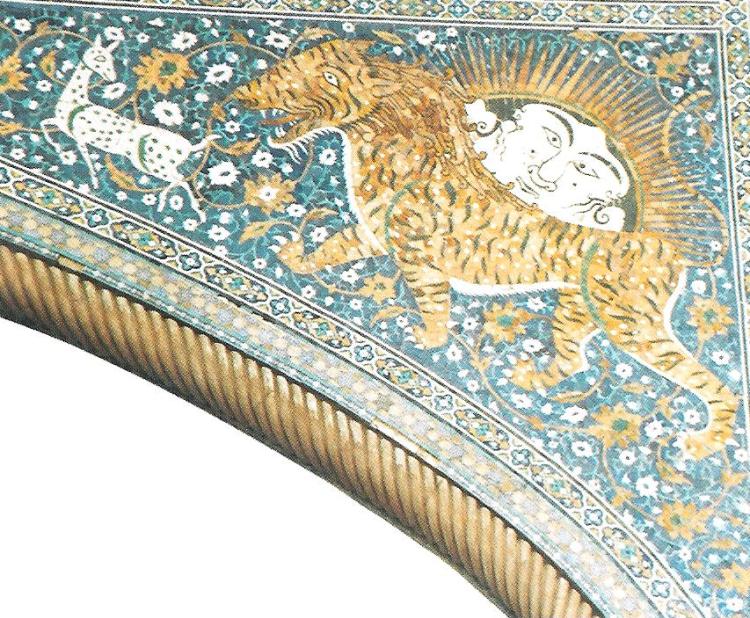

The “Shir Dar” (Lion’s gate/doorway) of the Islamic college at Samarkand built originally in 1627 (Nafīsī, 1949, p. 62). The sun motif is characterized by Kriwaczek (2002, picture Plate 1) as ”…the image of Mithra, the rising and unconquered sun, Zoroastrian intercessor between God and Humanity” (Source: Kriwaczek, 2002).

I can well imagine what the fine citizens of ancient Sogdiana were like having spent time in Kashmir. Another Central Asian Persian people, trade is in their blood. With its teeming markets and colorful bazaars, Alexis kept mumbling, “We’re in Central Asia. Finally, Central Asia.” Sultan kept repeating, “To make a sale is to make a friend.” Talking over unending cups of Kashmiri chai– cinnamon and cardamom, and a dash of milk– it was always how business was going, or talk about some purchase–buying a new silk carpet or a Pashima shawl– that dominated conversation. This is how I imagine the Sogdians.

A Tajik lady in a bazaar in Dushanbe displaying the local brand of Persian bread known as “Kulcha” (Photo: Travel Begins at 40). As noted in the article “Dushanbe Lost in Time”: “Bar the cheap, Chinese electronics for sale in the ramshackle stalls, this walled-in, colour-soaked bazaar feels like an independent microcosm stuck in an aged Persian time warp”.

A Tajik lady in a bazaar in Dushanbe displaying the local brand of Persian bread known as “Kulcha” (Photo: Travel Begins at 40). As noted in the article “Dushanbe Lost in Time”: “Bar the cheap, Chinese electronics for sale in the ramshackle stalls, this walled-in, colour-soaked bazaar feels like an independent microcosm stuck in an aged Persian time warp”.

Starting at the eastern edge of the Persian empire, the Kingdom of Sogdiana reached almost to Kashgar. There, the Silk Road split into two routes: one north and one south of the desert of death. With a name which means “if you go in, you’ll never come back out,” the Taklamakan Desert is one of the largest sandy deserts on earth. With virtually no available water, it was extremely hazardous to try and cross the desert, and so the Silk Road split into two routes. And, it was along these two routes skirting the northern and southern edges of the Desert that a string of Buddhist Kingdoms dotted the oases.

The procession of the ambassadors painting at Afrasiab (Source: Faqsci in Public Domain); this painting is believed to have been commissioned sometime in 650 CE by Varkhuman, the king of Samarkand.

On the Southern Route, there was the Kingdom of Khotan–famous for its exquisite jade and felt carpets; and Kashgar– which has always been a city of legend. Of course, the world’s most famous Silk Road site, Dunhuang, was also located just west of where the Northern and Southern Routes met back up again. Famous for its library, Dunhuang is also the location of the Mogao Caves of A Thousand Buddhas. Located just West of the Jade Gate, Dunhuang was just West of China proper.

A Tajik woman in Ihkashim (Source: Nick & Dariece – Goats on the Road Travel Blog). While the notion that Tajiks are the direct descendants of the Soghdians remains researched, Tajiks are the descendants of peoples of Iranian stock who dominated much of Central Asia and Eurasia until the arrival of Turco-Hun peoples, especially from the 5th-6th centuries CE.

Along the Northern Route were the oasis cities of Gaochang, Turfan, Urumqi, and of course, Kucha. Gaochang was perhaps the most important Buddhist Kingdom. Built at the foot of the Flaming Mountains, the Bezeklik Caves of a Thousand Buddhas, located close to the ancient city, are renown for their dazzling murals. With paintings of Uighur princesses and Western traders, the place during Tang times was a magnet for people from the four corners of the civilized world.

To me, while I can imagine Sogdiana in all its Persian glory– that there existed flourishing Buddhist Kingdoms which were centers of great scholarship in this inhospitable desert– well, it actually boggles my mind. But, the cities located along the desert were, in fact, places of learning where the greatest minds of the Buddhist world gathered to discuss Buddhist doctrine.

A Chinese Qi depiction of Soghdians (Picture and caption from Kaveh Farrokh’’s lectures at the University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division and were also presented at Stanford University’s WAIS 2006 Critical World Problems Conference Presentations on July 30-31, 2006).

These cultural exchanges were conducted in the languages of scholarship of the day–Tibetan, Sanskrit, Chinese and various Prakrit. One of the most famous translators of Buddhism, Kumarjiva, was from Kucha (his mother was a Kuchan princess while his father was Kashmiri). So brilliant some legends have it that he was carried off by the Chinese. Dragged back to the capital he was made to translate the important Buddhist treatises of the time. Others say he went willingly. Whatever the case were it not for Kumarjiva, China and Japan would probably not have quite the same cast of Buddhism it has today– such was his influence.

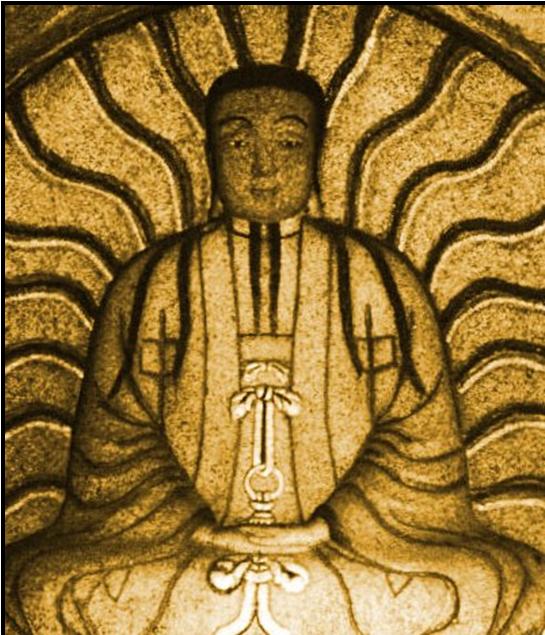

The 3rd century CE Iranian prophet Mani as depicted in a Chinese temple carving in Dunhuang Picture and caption from Kaveh Farrokh’’s lectures at the University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Divisionand were also presented at Stanford University’s WAIS 2006 Critical World Problems Conference Presentations on July 30-31, 2006).

The great problem of the time: how to translate abstract philosophical terms from Sanskrit (a language with an extraordinarily rich philosophical lexicon that perhaps more then any language extinct or extant could express abstract concepts with specific vocabulary) into Chinese (a language poor in abstract vocabulary). Words had to be invented.

It was a huge linguistic gap that had to be overcome. Herculean. Kumarjiva, to get the closest Chinese approximation of the Sanskrit possible would engage in long discussions with a hundred students to try and fit a Sanskrit word to the Chinese mind before trying to come up with a new combination of characters.

Something very similar went on when China opened up to the west in more modern times. Both the Chinese and the Japanese had to think quick to come up with new vocabulary to express Western concepts of democracy or freedom (an entire lexicon, had to be come up with for terms used in discussing the fine arts before Japan could participate in one of the legendary World Exhibitions, for example).

Fresco along the Tarim Basin, China depicting an Iranian-speaking Buddhist monk (Kushan, Soghdian, Persian or Tocharian?) They call him the world’s greatest translator. A proponent of i-yaku 意訳 (meaning-oriented translation) over that of choku-yaku 直訳 (direct or literal translations), Kumarjiva is not only known for the tremendous breadth of his translations but also for the beautiful flowing smoothness of the language– which is to say it reads beautifully. And, it needs to be stated again that is is all the more of an achievement because of the fact that he was working in what is the most obtuse area of Buddhist philosophy. Born a Theravada Buddhist, Kumarjiva converted to Mahayana Buddhism during his student days in Kashgar and spent much time working on advancing the ideas contained in the great Indian philosopher Nagarjuna’s Madhyamaka theory. “Form is void, void is form” — Heart Sutra The philosophy is way too complicated for me to even attempt to think about, and due to its slippery slope vocabulary that attempts to explain a state of existence where “nothing comes into being independently” (got that?), the nature of the Chinese language just could not cope. Kumarjiva devoted the later years of his life with the task of translating this body of work, but many gnawing questions remained. It was to this task that our hero, Xuanzang, the Tang period Buddhist monk who made his historic “Journey to the West” devoted his entire life. If you don’t know who he is– you should. In East Asia, he is a household name– and even in India, most educated people know of the great travels of Xuanzang. A depiction Xuanzang made during Japan’s Kamakura period (12th– 14th century), currently housed in the Tokyo National Museum (Source: Alexcn in Public Domain). Passing through the Jade Gate, Xuanzang traveled through all the Buddhist Kingdoms along the Northern and Southern Route before turning south to India. He almost didn’t make it to India, though, so intent was the devout Buddhist King of the Kingdom of Gaochang to keep the pilgrim there that the King tried to hold him there hostage. Rather than from any ill-will, the King quite simply could not bear to let such a stimulating conversationalist and brilliant debater leave his realm. You can hardly blame him, actually. Some people consider Xuanzang to be the greatest traveler of all time. Marco Polo perhaps traveled further in terms of distance– but well, that was about 450 years later (and things were more comfortable then). More importantly, though, while Polo traveled for personal reasons of wealth and fame, our man from Chang-an traveled to find the Truth– to understand the nature of reality, not just for himself but for the sake of all sentient beings. His great journey took him first across the desert Kingdoms and then to Kashmir, which was a great center of Buddhist learning at the time. He continued South where he ended up at Nalanda University. There he studied Buddhist philosophy, logic and Sanskrit. Returning to China, he hauled a library of books back with him and spent the remainder of his days teaching and translating.