The article below was written in a letter Sharon Turner in 1827 and was first posted in the CAIS (Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies) venue hosted by Shapour Suren-Pahlav.

Kindly note that the images and accompanying descriptions inserted below do not appear in the original article posting in CAIS.

===========================================================

If more important communications be not, at the present moment, occupying the attention of the Royal Society of Literature, it may not perhaps be wholly uninteresting, if I submit to its consideration a few circumstances in regard to the Asiatic origin of our Anglo-Saxon ancestors, which have lately occurred to me on examining the affinities of their ancient language.

It has been stated in the History of the Anglo-Saxons, that the most probable derivation of this people which had been suggested, was that which deduced them from the Sakai or Sacae, who, from, the Caspian, besides branching into Bactriana on the east, had also spread westward into the most fertile part of Armenia, which, from them, as we learn from Strabo, was called Sakasina.

Pliny terms the Sakai, who settled there, the Sacassani; which is so similar in sound to Saca-sunu, or the sons of the Sakai, that we are tempted to identify the two appellations. It was Goropius Becanus who first hinted this etymology: the celebrated Melanchthon adopted it; and though, as is usual on such subjects, others doubted and disputed, our Camden gave it the sanction of his decided preference.

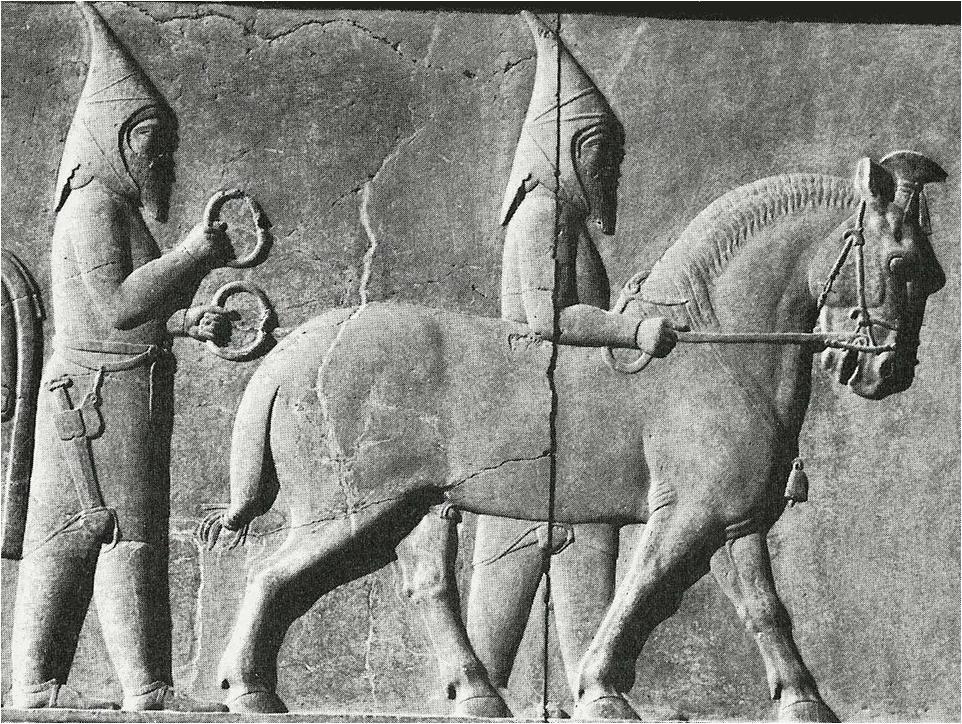

Eastern Scythians or “Saka Tigrakhauda” (Pointed cap Saka) as depicted in Persepolis. The Scythians played an important role in the military machine of the Achaemenids. A branch of the Scythians or Saka, the Parthians, were to revive the Iranian kingdom after Alexander’s conquests and his Seleucid successors.

It appeared to me to be the most rational derivation which had been mentioned; and the fact that Ptolemy, writing in the second century after Strabo and Pliny, actually notices a Scythian people, who had sprung from the Sakai, by the very name of Saxones, seemed to verify the conjecture, that the appellative Saxones did originate from Saca-sunu, or the sons of the Sakai.

The Romans spelt the word with a c instead of a k, and we therefore call them Sacae, with the s sound of the c.But this is only our mispronunciation of the Roman c; for we find that Cicero’s name is written in the Greek authors who mention him, as Kikeroo.

The preceding derivation thus leads to the opinion, that the progenitors of our Anglo-Saxon ancestors came from Asia into Europe; and that before they made this emigration, they had dwelt in Armenia and in the regions about the Caspian.

The Honourable Mr. Keppell, in his late interesting travels, visited this country, and thus notices it. After crossing the river Arras – the Araxes of Plutarch – he says:

“Between this river and the Kur – the ancient Cyrus or Cyrnus – is the beautiful province of Karabaugh, formerly the country of the Sacae or Sacassani, a warlike tribe of Scythians, mentioned by Pliny and Strabo, and supposed to be the same people as our ancient ancestors the Saxons.”

After quitting Karabaugh, Mr. Keppell proceeded to Shirwan, the Albania of the ancients. The beautiful province of Karabaugh, between the Arras and the Kur – the ancient Araxes and Cyrnus – may therefore be considered as one of the Asiatic localisations of our Anglo-Saxon ancestors. The Kur has been the late boundary of the Russian acquisitions in this district.

The late war between the Russians and the Persians has been chiefly carried on in or near the regions where the ancient Sakai or Sacassani were seated, and which appear to have begun from the south of the Kur. If the Russians make any further acquisitions in these parts, they will become possessed of the country of our Sakai ancestors.

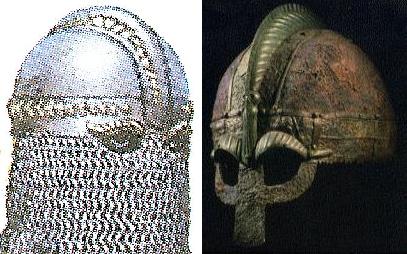

Viking Helmet (Right; Picture Source: English Monarchs) and reconstruction of earlier Sassanian helmet at Taghe Bostan, Kermanshah, Iran (Left; Picture Source: Close up of Angus Mcbride painting of Sassanian knight at Taghe Bostan, Wilcox, P. (1999). Rome’s Enemies: Parthians and Sasanid Persians. Osprey Publishing, p.47, Plate H1).

These circumstances, drawing the mind to this part of the world, led me to recollect that former antiquaries had observed a few words in the Persian language to resemble some in the Saxon. Camden mentions, that “the admirable scholar, Joseph Scaliger, has told us that fader, muder, brader, tuchter, band, and such like, are still used in the Persian language, in the same sense as we say father, mother, brother, daughter, and band.” (Camden’s Brit. Introd. cxxiii.)

Musing upon this intimation, it occurred to me, that if five words, so much alike as these, were found in the two languages, an attentive comparison of the Persian with the Anglo-Saxon might discover many more, if the allegation were really true, that the Saxons had come from these regions; and in that case, if any considerable number of similarities were really existing in the two languages, they would tend to confirm the belief, that the origin of our Saxon forefathers should be thus sought in Asia, and that their primeval ancestors had gradually moved from the Caspian Sea to the German Ocean.

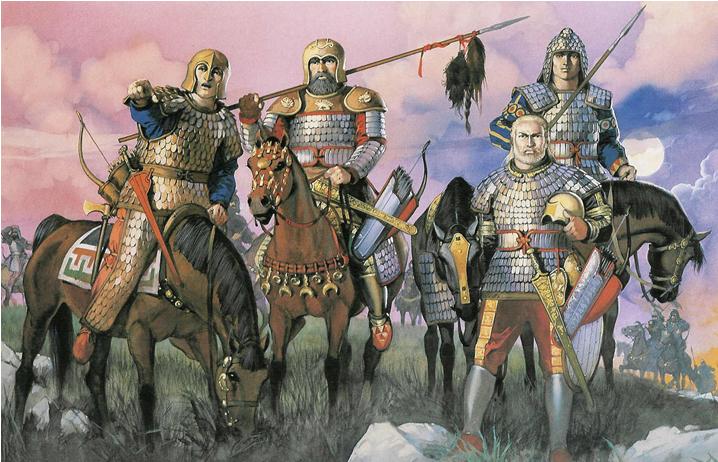

Scythians on the steppes of the ancient Ukraine. Scholars are virtually unanimous that the Scythians were an Iranian people related to the Medes and Persians of ancient Iran or Persia (Painting by Angus McBride).

This view of the subject induced me to attempt a cursory examination, whether such resemblances could, by a general inspection, be perceived, as would satisfy the mind that the chorographical relationship was not an unfounded conjecture.

But it was obvious, that whatever the ancient identity between these languages may have been in their original state, no very great proportion of it could be expected to be visible now, because the Saxons have been separated from these regions at least 2000 years; and in their progress along the north of Asia, and through the whole breadth of the upper surface of Europe, and amid all the evils, sufferings, triumphs, and events, which must have befallen them before they reached the mouth of the Elbe; and from the new scenes and conflicts which accompanied their three centuries of depredations on the Roman empire and upon the ocean, and which afterwards, for four hundred years more, awaited them in Britain, before those works were written which display their language to us; – from all these causes, the Anglo-Saxons, in the days of Alfred, must have used a very different tongue, in the mass of its words, from that simpler and ruder one which their progenitors had conversed with in the beautiful province of Karabaugh, and on the Araxes, the Kur, and the Caspian.

So, during the same lapse of time, the Persian language has ceased to be what it was in the days of Cyrus or Darius. It has become, within the last 1,000 years, the most polished language of the Eastern world, and has been most exercised in clothing with select and ornate phrase the finest effusions of the Oriental genius.

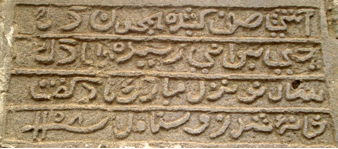

Persian (Zoroastrian) inscription in Ateshgah (Source: Farroukh Jorat).

Modern Persian can, therefore, be scarcely less unlike the original language of those, in his war, against whom the self-confident Julian found an early grave, instead of the victorious triumph he expected, than our present English is to the Anglo-Saxon of the same period. Neither Persian nor Saxon are now what they were when the Sakai and the Persae confronted each other on their dividing rivers, and from their bordering mountains. Hence no such pervading identity could be expected as may yet be traced between the Welsh, the Bas Breton, the Irish, and the Gaelic, however originally similar.

The likeness would be also less, because the Saxons did not spring from the Persians. No one has alleged this parentage. The Sakai were the relatives only, not the children of the Persae. So far from any filial or paternal feelings existing between them, the most furious hostilities disparted the two tribes; and at one epoch, the Persians, by attacking the Sakai by surprise, nearly exterminated them.

This disaster disinclined our valuable antiquary, Sheringham, from adopting this derivation of our ancestors. But as it is manifest that no attack of surprise could annihilate at that time more than the forces which were surprised, the calamity is more likely to have been a reason for the rest of the Sakai, after this weakening catastrophe, to have moved hastily out of their pleasing settlements in those parts of the world, and to have migrated westward to a safer locality.

The main fire altar at the Atash-kade (Zoroastrian Fire-Temple) of Baku in the Republic of Azerbaijan (known as Arran and the Khanates until 1918) (Picture Source:Panoramio). This site is now registered with UNESCO as a world heritage site.

This defeat may have forced them from Armenia to other districts nearer Europe; and the war of the Romans, or of Mithridates, or similar disturbing causes, may have afterwards impelled them to proceed onward to the Vistula, and at last to seek refuge on the islands and peninsula of the western extremities of the continent.

The probability is, that all the tribes which anciently inhabited the immediately conterminous countries were, for the most part, branches of the same main parental stem. The Persae, the Sakai, and their neighbours, may be therefore considered as ramifications of the great Scythian stock – part of the audax genus of Japetus, or Japhet; and as such, although the old Persians and the Sakai would not have spoken the same language in all its words and forms, yet their respective tongues would be dialects of their family original, and therefore would have many terms in common, as we still find between the ancient Franco-theotisc and the Saxon.

Of these assimilating terms, I expected that many fragments would be preserved, both in the Anglo-Saxon and in modern Persian, notwithstanding all the changing fortunes of the two nations; but that they would, from these mutations, exist and be perceptible now only as fragments.

Remains of the Temple of Mithra at Carrawburgh, England (Source: Britain Express). The culture 0f Mithras continues to endure among the Iranians (within Iran and the Kurds of the Near East beyond modern-day Iran. The Kurds speak West Iranian languages (i.e. Kurmnaji, Gowrani, etc.) that are akin to Persian and Luri.

Proceeding on this principle – that if the ancestors of the two nations did once live in vicinity to each other, although this was 2000 years ago, some indications of their neighbourhood would appear from subsisting similarities in their languages, and expecting to find these only as occasional fragments, I have compared the Anglo-Saxon with the modern Persian. The result has been, that, upon a general examination, I have found 162 Persian words which have a direct affinity with as many Anglo-Saxon terms of the same meaning; and these I beg leave to submit to the notice of the Society.

But before I attach the list of these, I will take the liberty also of mentioning, that I thought it right, after these similarities had been ascertained, to consider that two other languages, older than the modern Persian, had prevailed in that country. These were the Pehlvi and the Zend. The latter, the most ancient that we know of in those parts from actual specimens; the other, the Pehlvi, an intermediate one, in point of chronology, between the Zend and the Persian.

A detail of the painting “School of Athens” by Raphael 1509 CE (Source: Zoroastrian Astrology Blogspot). Raphael has provided his artistic impression of Zoroaster (with beard-holding a celestial sphere) conversing with Ptolemy (c. 90-168 CE) (with his back to viewer) and holding a sphere of the earth. Note that contrary to Samuel Huntington’s “Clash of Civilizations” paradigm, the “East” represented by Zoroaster, is in dialogue with the “West”, represented by Ptolemy. Prior to the rise of Eurocentricism in the 19th century (especially after the 1850s), ancient Persia was viewed positively by the Europeans. For more see Ken R. Vincent: Zoroaster-the First Universalist…

Of both the Zend and the Pehlvi, M. Anquetil found some specimens among the ancient manuscripts which he consulted in exploring and translating the Zendavesta, or sacred book of the still subsisting worshippers of the sacred fire in those regions. Recollecting this fact, I have been led also to look into these specimens, and I have observed fifty-seven words in these fragments of the Zend language, which resemble as many in the Anglo-Saxon, and forty-three of accordant similarities between our old tongue and the Pehlvi.

These one hundred and sixty-two Persian words, fifty-seven Zend, and forty-three Pehlvi, present to us two hundred and sixty-two words in the three languages that have prevailed in Persia, which have sufficient affinity with as many in the Anglo-Saxon to confirm the deduction of our earliest progenitors from these regions of ancient Asia.

The Three Wise Men as depicted in Ravenna (Sant’Apollinare Nuovo), Italy (Source: Public Domain). Note the European depiction of Partho-Sassanian Iranian dress, caps and cloaks.

That these affinities are too many to be ascribed to mere chance, there seems to be no difficulty in affirming. But on adverting to the positions suggested in my former papers, of a primeval oneness of language among mankind, and of the abruption of that into the diversities which now pervade the world, it is a reasonable question, whether these two hundred and sixty-two similarities are only remains of the primitive unity, or whether they be indications of specific subsequent relationship of two of the newer languages that were formed after the dispersion.

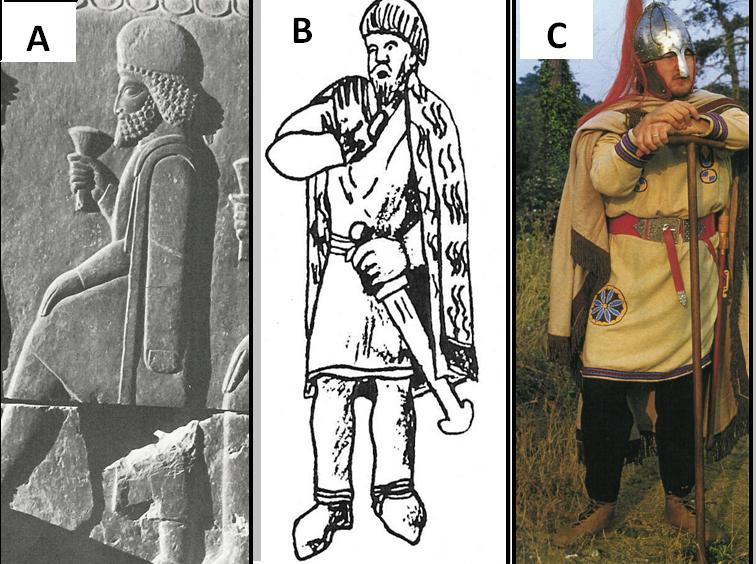

The Iranian Kandys cape and its legacy in Europe (click to enlarge). (A) Medo-Persian nobleman from Persepolis wearing the Iranian Kandys cape of the nobility 2500 years past (B) figure of Paul dressed in North Iranian/Germanic dress from a 5th century ivory plaque depicting the life of Saint-Paul (C) reconstruction by Daniel Peterson (The Roman Legions, published by Windrow & Greene in 1992, p.84) of a 4th-5th century Germanic warrior wearing Iranian style dress and the Kandys. The Iranian Persepolis styles of arts and architecture continued to exert a profound influence far beyond its borders for centuries after its destruction by Alexander (Pictures used in Kaveh Farrokh’s lectures at the University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division and Stanford University’s WAIS 2006 Critical World Problems Conference Presentations on July 30-31, 2006).

The Iranian Kandys cape and its legacy in Europe (click to enlarge). (A) Medo-Persian nobleman from Persepolis wearing the Iranian Kandys cape of the nobility 2500 years past (B) figure of Paul dressed in North Iranian/Germanic dress from a 5th century ivory plaque depicting the life of Saint-Paul (C) reconstruction by Daniel Peterson (The Roman Legions, published by Windrow & Greene in 1992, p.84) of a 4th-5th century Germanic warrior wearing Iranian style dress and the Kandys. The Iranian Persepolis styles of arts and architecture continued to exert a profound influence far beyond its borders for centuries after its destruction by Alexander (Pictures used in Kaveh Farrokh’s lectures at the University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division and Stanford University’s WAIS 2006 Critical World Problems Conference Presentations on July 30-31, 2006).

Both the nature and the number of the analogies I have remarked satisfy my own mind that they are more truly referable to the latter than to the former cause, and therefore I will proceed to enumerate them, as corroborating testimony of our Sacassenian derivation, beginning with the Persian affinities, and then proceeding to those of the Zend and the Pehlvi.

PERSIAN, ANGLO-SAXON

am, I am.

aelan, to burn

alaw, a flame of fire

afora, a son

afa, the eldest son

andega, an appointed term

andan, a term

abidan, to abide

abadan, an abode

are, honour

aray, decoration

arian, to honour

arayidan, to adorn

ase, as

asay, like

andget, the intellect, sense

angar, reason.

andgashtan, to think

enge, trouble

anjam, grief.

andjugh, a sigh

angel, a hook

angulah, a button

ewe, water

aw, water

earmth, misery

urman, trouble

ende, the end

anjam, the end

berend, fruitful

bar, fruit

beeran, to carry

bar, a load

brother, a brother

bradar, a brother

barn, a barn

barn, a covered place

bearn, a son

barna, a youth

bedan, to offer

bedroz, a present

balew, depraved

bulad, a malefactor

beal, destruction

bulaghan, a calamity

bilewite, simple

biladah, foolish

beado, cruelty

bada, wickedness

barbacan, a front tower

burbik, a portico

bur, a chamber

barkh, an open room

blessian, to bless

balistan, to bless

blad, fruit, the blade

balidan, balandan, to grow

basing, a pallium, a chlamys

basuian, to be clothed in purple

baz, a habit, rich dress

bered, vexed

barat, disgusted tired

beard, a beard

barbar, a barber

breost, the breast

bistan, the breast

bysmor, infamy

bazat, a crime.

basaj, depravity

bysgu, business

bishing, business

bile, the beak, the bill

bull, the beak

bio, I exist

bud, existence

benn, a wound

bunawar, a sore

bil, a mattock

blowan, to flower

bilak, a flower

bidan, to expect, to await

bidar, watching.

bidari, vigilance

byld, firmness

bilah, firm

bend, a bond

band, a band, a chain

bendan, to bind

bandan, bandidan, to bind

bold, a town

balad, a city

bolt, a house

bulud, a dwelling

byan, to inhabit.

binland, cultivated land

bingha, a dwelling

beam, the sunbeam.

beamian, to beam

bam, the morning

sifer, pure, chaste

saf, pure

safa, purity

samod, together, in like manner

saehim, a partner, even

mirran, to hinder

maraw, go not.

marang, a bar

man, wickedness

mang, cheating, a thief

mona, the moon

mang, the moon

mxden, a maiden

madah, a female

moder, mother

madar, mother

mara, the night-mare

mar, sick

mal, pay, reward, tribute

malwar, rich

maldar, a rich man

mani, many

mali, many

morth, death

murda, dead

morther, murder

murdan, to die

mearc, a limit

marz, a limit

mus, a mouse

murz, a mouse

must, new wine

mustar, new wine

na, not

nah, not

naegl, a nail

nakhun, a nail

nafel, the navel

nal; the navel

nama, a name

nam, a name

iiameutha, illustrious

nami, illustrious

necca, the neck

nojat, the collar

neow, new

no, new

nu, now

nun, now

nigan, nine

nuh, nine

hol, health

hal, quiet, firmness

hare, hoary

harid, venerable

isa, ice

hasir, ice

eam, I am

hayam, I am

iuc, a yoke

yugh, a yoke

rad, a road

rah, a road

reste, quiet

rast, secure

duru, a door

dar, a door

deni, slaughter

dam, a groan, black blood

dim, obscure

damah, a cloud

gabban, to deride

ghab, a foolish bitter expression

gaf, loquacious

guftan, speech, to relate

cu, a cow

go, a cow

gers, grass

gryah, grass

gifr, greedy

guri, avarice

faeen, fraud

faj, a lie

sum, some

suman, a little

reel, prosperity

salaf, luxurious

steorra, a star

sitarah, a star

losewest, deception

losidan, to deceive

leogan, to tell a lie

lay, lying

hlogun, they laughed

lagh, a jest. lof, praise

laf, praise

lufa, love

laheb, love

lam, lame

lam, crooked

lang, lame

lippa, the lip

law, the lip

laf, the remainder

lab, remaining

less, the less

lash, small

lar, learning

lur, ability

lust, delight

lustan, to sport

lust, luxuriousness

lashan, nice, soft

blyd, tumult.

hlydan, to rage, to make a noise

lud, furious altercation

list, knowledge

listum, skilfully

lazir, clever

thu, thou

to, thou

thinan, to decline, to become thin

tanik, thin

tinterg, torment

tang, tight

tintregan, to torture

tangi, anguish

tawian, to cultivate

tan, an inhabitant

teman, to teem, to bring forth abundantly

toma, twins

wen, hope

awanidan, to hope

wenan, to expect

awanidan, to expect

ysel, a spark

azar, fire

raene, pride, glorying

awrang, power, glory

ae, a law

aym, a law

paeca, a deceiver

pak, vile

paecan, to deceive

pakh, ingratitude

paeth, a path, a footway

pay, pa, a footstep

pal, a stake

palar, a beam of wood

paell, colour

paludan, to besmear

pyndan, to shut up, impound

pynding, a fettering

paywand, a chain, a shackle

to, to

ta, to

taer, a tear

tar, moist

tarb, torture

taeran, to tear

tarakidan, to split

telan, to tell

talagh, a voice

teiss, affliction

tasah, grief

teisse, a stripe

tazyanah, a scourge

tir, a lord. tir, a chief

tir, glory

tur, a hero, bright

siofotha, bran

sapos, bran

seel, time

sal, a year

seepah, age

sul, a plough

suli, a plough

sac, discord, quarrel

sakht, violent, stubborn

sur, surig, sour

sirka, sirkah, vinegar

salh, a willow

salah, a wicker-basket

sorg, sorrow. sog, grief

sugwar, sorrowful

sol, solen, a shoe, a sandal

salu, a coarse shoe

supwah, a shoe

sole, the sole

sul , the sole

thunar, thunder

tundar, thunder

thunrian, to thunder

tundidan, to thunder

tan, a bud

tundar, the bud of a leaf

It is remarkable that all, or nearly all, of the Anglo-Saxon words spelt in the Lexicon with sc, which are now used in our English phrase, are at present pronounced by us as sh, and are written with this orthography. Thus the Anglo-Saxon sceap, scyp, sco, scine, and sceam, are spoken by us as sheep, ship, shoe, shine, and shame.

Whether the sh was the original sound of those words, which, by a sort of conventional orthography, were written as sc by our ancestors, to distinguish their sound of sh from the proximate one of s, or whether it became changed by one of those gradual alterations of pronunciation which occur in all languages from various causes, we cannot now decide; but the Persian has some analogous terms with the sh, instead of the sc, as

sea, excellent

shadbash, excellent

seama, shame, bashfulnes

sharm, shame, bashfulness

shama, naked

sceaming, confusion

shamidan, to be confounded

sceaphan, to shape, to put in order

shaplidan, to smooth

sceaft, a shaft, an arrow

shaftu, a quiver

sceaft, a point

shafar, the edge

sceawian, to see

shuwaz, the eye.

The other resemblances which I have remarked between these two languages are:

faegan, glad

farghan, gladness

faeran, to go

feridan, to walk

faroth, a journey

faraz, progress

fyr, fire

faroz, inflaming

ferhth, the mind

farzah, wisdom, knowledge

ferht, fear, fright

farasha, dread, trembling

The congruities which I have perceived in the few specimens that have been published of the Zend with the Anglo-Saxon are the following:

beran, to bear

bereete, to bear

ba, both

betim, the second

the, thee

te, thee

eahta, eight

aschte, eight

dochter, daughter

dogde, daughter

dohte, he did

daschte, he did

steorran, stars

staranm, stars

frend, a friend

frem, a friend

feder, a father

feder, a father

mid, with

mad, with

meder, mother

mediehe, mother

medo, mead

medo, wine

me, me

man, me

metan, to measure

meete, measure

med, a recompense

mejdem, a recompense

maest, chief

meze, meso, great

micle, much

mesche, much

mecg, a man

meschio, a man

mal more

mae, great

na, not

noued, not

nafel, the navel

nafo, the navel

we, an oak

hekhte, an acorn

hera, a lord.

heretoge, a chief

herete, a chief

paeth, a path

petho, a way

purl pure

peratche, pure

uppa, above.

upper, above

opero, above

threo, three

thre, three

thrydde, the third

thretim, the third

thu, thou

thvanin, thou

bane, a floor, a board

baenthro, a floor, a board

rot, splendid.

rof, illustrious

erode, illustrious

astandan, to subsist

asteouao, existence

beoth, they are

beouad, he is

beo, be it

boiad, be it

theof, a thief

teio, a great thief

dreori, dreary

drezre, a desert

daeth, death

dajed, he is no more

rewa, order

reso, he puts in order

reswian, to reason

razann, intelligent

froe, a lord

frethem, greatness

guast, the spirit

gueie, the soul

mxnde, he mentioned

manthre, words

midda, middle

meiao, middle

morth, death

mrete, mortal

merran, to mar

merekhsch, to destroy

gear, year

yare, year

earmth, poverty

armete, humility

starian, to look at

astriete, he sees

ba, both

bee, two

singan, to say

senghan, a word

scir, sheer, pure

srere, pure

snid, a cut

snees, he strikes

seon, to see

sodern, to see

gnad, he bruised

ghnad, he strikes

athe, easy

achiato, easy

scina, shina, brilliant

scheeto, brilliant.

I will now only trouble the Society with the few coincidences that I have found in looking over Mr. Anquetil’s short vocabulary of the Pehlvi, as he has printed it from his old manuscripts.

bonda, one bound

bandeh, a slave

nam-cutha, famous

nameh, famous

starian, to look at

astared, he sees

halig, holy

halae, pure

eahta, eight

ascht, eight

sare, troublesome

sareh, wicked

morth, death

marg, mortal

a-marg, immortal

thu, thou

tou, thou

sex, six

sese, six

bysmor, opprobrium

besche, wicked

suht, languor

satoun, weak

dom, legal judgment

din, law

reasan, to attach

resch, a wound

secgan, to say

sokhan, a word

gaf, loquacious

goft, he said

ofer, over, above

avvar, above

dem, slaughter

damma, blood

med, recompense

mozd, recompense

cneou, knee

djanouh, knee

steorran, stars

setaran, stars

setnian, to be in ambush

sater, war

sceacan, shakan, to shake, to pluck

schekest, he breaks

athe, easy

asaneh, easy

cu, cow

gao, ox or cow

ma, more

meh, great

bar, bare

barhene, naked

morth, death

mourd, he dies

mourdeh, mortal

meder, mother

amider, mother

nafel, the navel

naf, the navel

na, no

na, not

bog, a branch

barg, a leaf

purl, pure

partan, pure

agytan, to understand

agah, understanding

ac, an oak

akht, an acorn

brader, brother

berour, brother

bye, a habitation

bita, a house

secg, a little sword

saex, a knife

sakina, a knife

clypian, to call out

cald, called

kala, crying out

mare, greater

mar, great

necan, to kill

naksounan, I kill

band, a joining

banda, a band

raed, a road

raeh, a way

eortha, earth

arta, earth.

From what I have seen of the three languages of ancient and modern Persia which I have inspected, I think that by a more elaborate investigation of all their analogies with the Anglo-Saxon, a greater number of satisfactory congruities might be traced.

But the preceding specimens will perhaps be sufficient to support the probability of the geographical derivation of our ancestors from the vicinity of the Caspian and of Persia; and we are now too many centuries removed from the actual period of the migration, to have any stronger evidence upon it than that of warrantable inference and reasonable probability.

I have the honour to be,

SHARON TURNER

32, Red Lion Square

22nd March, 1827.

N.B. – Since this letter was written, I have found several affinities of Anglo-Saxon words with others in the Arabic, Hebrew, Chinese, Sanskrit, Japanese, Coptic, Laplandish, Georgian, Tongo, Malay, and Susov, which are printed in the fifth edition of the Anglo-Saxon History [The History of the Anglo-Saxons].

These present a range of similitude, amid general dissimilarity, which corroborates the principle formerly stated – of the original unity of the primeval language, and of its subsequent abruption on the compulsory dispersion of mankind.

But these affinities are not, in each language, near so numerous as the preceding collections from the Persian and its cognate dialects; and therefore do not lessen the weight of the argument, that so many Persian correspondences with the Anglo-Saxon, favour the derivation of the latter nation from the ancient Sakasani, who inhabited the regions near the Kur.