Historians and archaeologists are entrusted with the task of examining and narrating the past.

This article aims to highlight the importance, leadership and deeply rooted courage of Iranian women throughout the history of Iran since ancient times. The women of Iran have been participants and engines of civil and political change throughout Iran’s ancient history. Below are a few examples that highlight the role tghat Iranian women have played in the history of Iran.

The ancient Burnt City (3000 BC): The Status of Women.

Archaeological evidence at the Burnt city near Zabol (in the province of Sistan-Baluchistan in southeast Iran) dated to 2000-3000 BC has revealed dramatic proof of the status and power enjoyed by the women of ancient Persia.

Although much of western scholarship has been primarily focused on investigating the rise of urban civilizations in ancient Mesopotamia, it is now acknowledged that the Iranian plateau has had an ancient urban tradition of its own.

The Burnt City (which encompasses 300,000 hectares) was a thriving and highly developed metropolis and host to four distinct civilizations. The site has yielded remarkable finds with respect to pottery and jewellery. In November 2004, archaeologists discovered the world’s most ancient backgammon game set (alongside its 60 related game pieces, dice, etc). Other discoveries at the site include the most ancient artificial eyeball, caraway seed and animated picture or “film”.

A report on the Burnt City was provided by the Cultural Heritage News (CHN) Agency of Iran by late December 2004.

One of the most interesting finds was the discovery of a large number of seals in the graves of women. Seals in antiquity were often symbols of power and authority. The Burnt City seals are of two kinds: governmental and personal.

An ancient seal from the Burnt City.

Mansour Sajjadi the Iranian archeologist supervising the Burnt City excavations, reported to CHN that:

“In the ancient world, there were tools used as a means of economic control. Whoever had these tools at his disposal was among the most powerful people in the society…“

Another remarkable series of discoveries at the cemetery of the Burnt City by the Sajjadi team was that 90% of the graves in which the seals were discovered belonged to women. Conversely, only a miniscule 5% of the seals belonged to men. Sajjadi further avers that:

“Since we know that seals were buried with their owners 5000 years ago, it is reasonable to think the most important seals for the economic activities in the burnt city belonged to women. As the men worked as farmers and craftsmen away from the city, they reasonably had to give the seals to women who were always in the city, so that they were able to solve the problems of the city immediately.”

More recent discoveries at the site indicate that the women of the Burnt City lived longer than the men. This was reported on June 22, 2009 by Iran’s PressTV News Service. The leader of these particular excavations at the Burnt City was Farzad Forouzanfar.

Forouzanfar has noted that men only lived to the age ranges of 35-45, while women survived as late as their 80s. His team also found that the number of inhabitants at the site stood at 6,000, revising the previously estimated number of 5000.

Noting that the area saw a number of population drops over time, Forouzanfar also stated that:

“…the number of the female inhabitants of the area was more than the males… The team also found that the remains of nearly 30,000 burials exist in Burnt City“.

Ancient Iranian women at War: The “Amazons” and the Achaemenids (5th century BC – 333 BC).

One of the areas that have received the least amount of attention by scholarship is the role women warriors of ancient Persia. The role of ancient Iranian female warriors can be traced back at least 2000 years, to the time of the Parthians (250 BC – 224 AD).

A Reuters newscast from Tehran in December 4, 2004 reported on the findings of an archaeologist who had been engaged in excavations near Tabriz, in Iran’s northwest province of Azarbaijan. A series of DNA tests revealed that the 2,000 year old bones of an entombed warrior and accompanying sword belonged to a woman. As noted by Alireza Hojabri-Nobari to the Iran-based Hambastegi Newspaper:

“Despite earlier comments that the warrior was a man because of the metal sword, DNA tests showed the skeleton inside the tomb belonged to a female warrior…”

According to Nobari, there were 109 such warrior tombs, and plans were in place to conduct DNA tests on the skeletons of the other ancient warriors of those sites as well.

The women warriors, known as “Amazons” by the ancient Greeks, were typical of such fighters who prevailed in Iran’s north (modern Gilan, Mazandaran, Gorgan) and northwest (modern Azarbaijan in Iran) as early as the 5th century BC or earlier. There have been numerous finds in the gravesites of ancient North-Iranic warriors known as the Scythians (Saka in Iranian) and their Sarmatian (or Ard-Alan) successors.

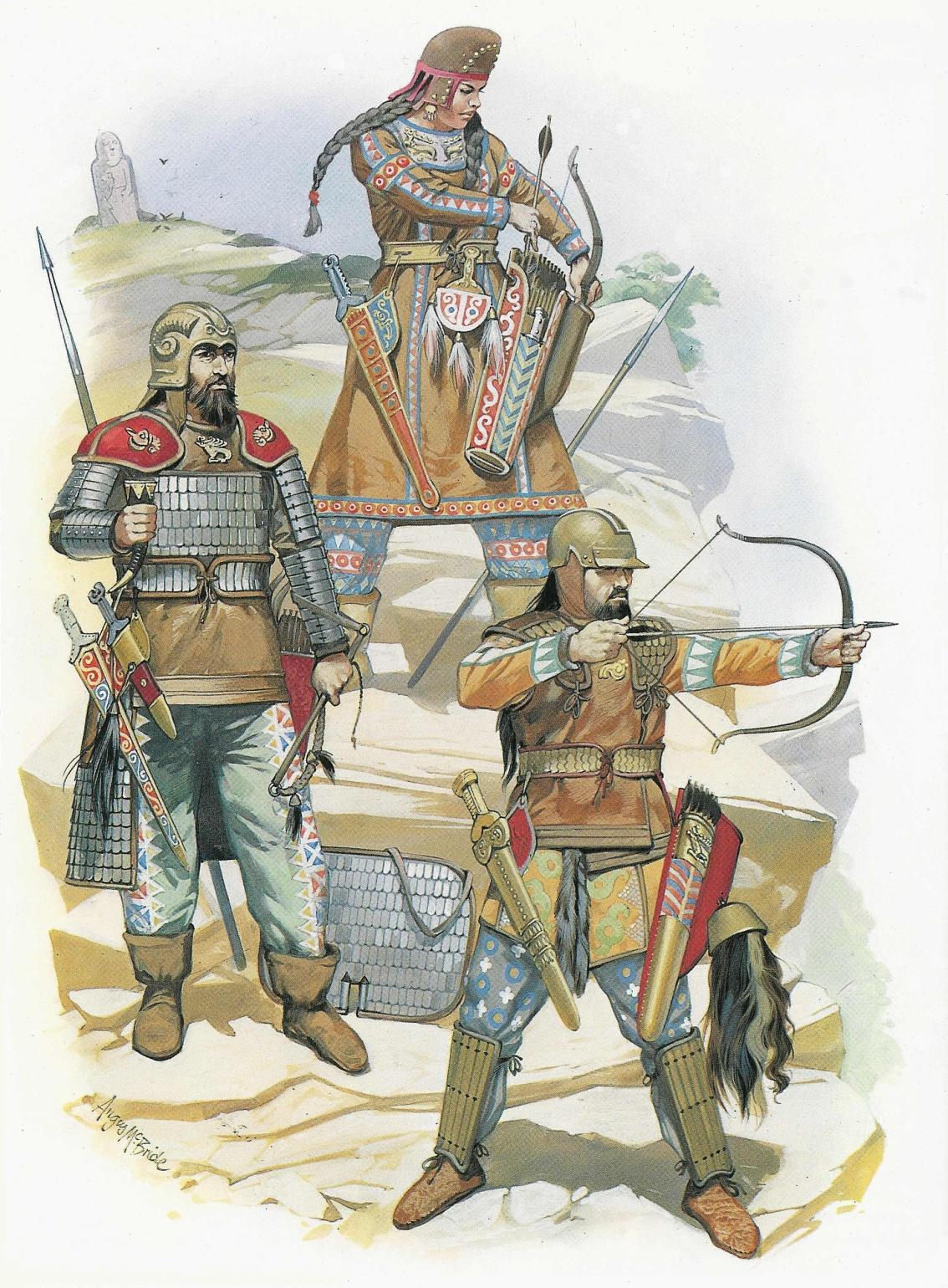

A reconstruction by Cernenko and Gorelik of the north-Iranian Saka or Scythians in battle (Cernenko & Gorelik, 1989, Plate F). The ancient Iranians (those in ancient Persia and the ones in ancient Eastern Europe) often had women warriors and chieftains, a practice not unlike those of the contemporary ancient Celts in ancient Central and Western Europe.

As noted by Mallory (1989, pp. 48-56, 78) these ancient north Iranian peoples were predominant in much of what is now known as the Ukraine, the northern Black Sea region in general and parts of Bulgaria and Rumania at the time of the Achaemenids.

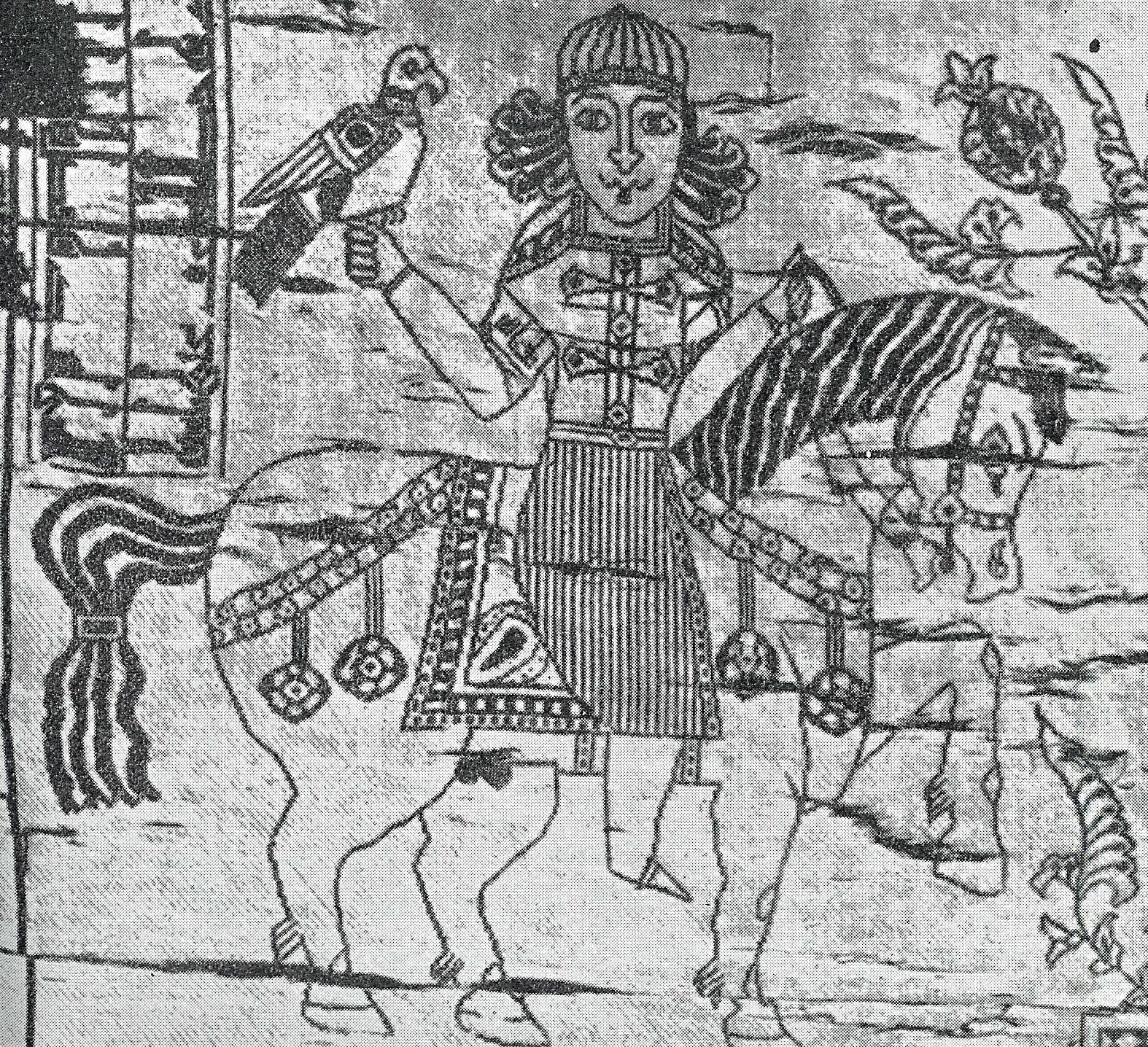

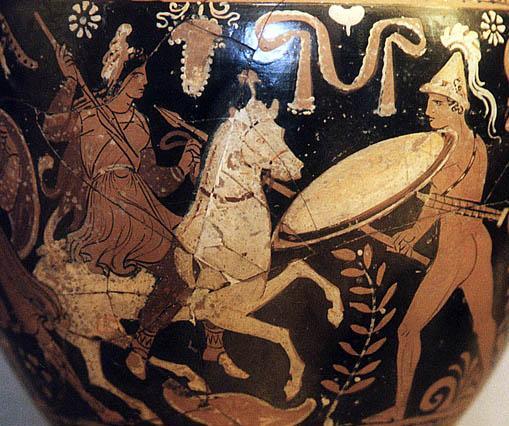

An ancient Greek vase depicting an Amazon female warrior (mounted on horse at left). Note the ancient Iranian dress, such as Medo-Persian style trousers, tunic, footwear, etc. The Greek warrior to the right appears with weapons and shields but no attire.

The burial mounds of the ancient Scythians/Saka known as “Kurgans” have often yielded the remains of women warriors who were buried alongside their swords. These Kurgan mounds have been discovered in various forms from the southern Ukraine all the way into the Caucasus and Iran (to the north and northwest).

By the time of the Achaemenids, women were also seen in positions of military leadership in the imperial armies of ancient Persia.

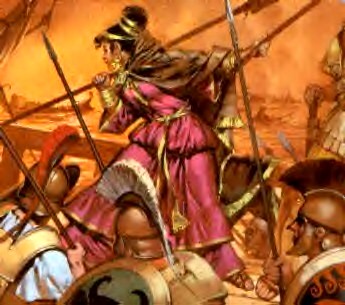

A reconstruction Artemesia of Halicarnassius (now in modern western Turkey) one of Xerxes’ most capable admirals during the failed invasions of Greece in 480 BC. The daring naval exploits of Artemesia reputedly led Xerxes to state that “…my men have become women and my women have become men”. Artemesia was also one of Xerxes’ chief military advisors.

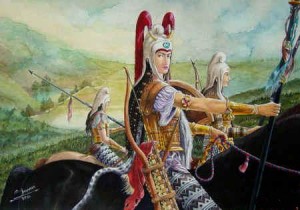

A reconstruction of a female Achaemenid cavalry unit by Shapur Suren-Pahlav. Many of the tribal elements in Iran, such as the Kurds and Lurs have been reported as fighting from horseback as late as the early twentieth century.

Iranian women in the Sassanian Era (224-651 AD)

Roman historical sources have reported on the exploits of the women warriors of the Sassanian Empire (224-651 AD). Zonaras (XII, 23, 595, 7-596, 9) states in reference to the forces of Shapur I that:

“…in the Persian army…there are said to have been found women also, dressed and armed like men…”

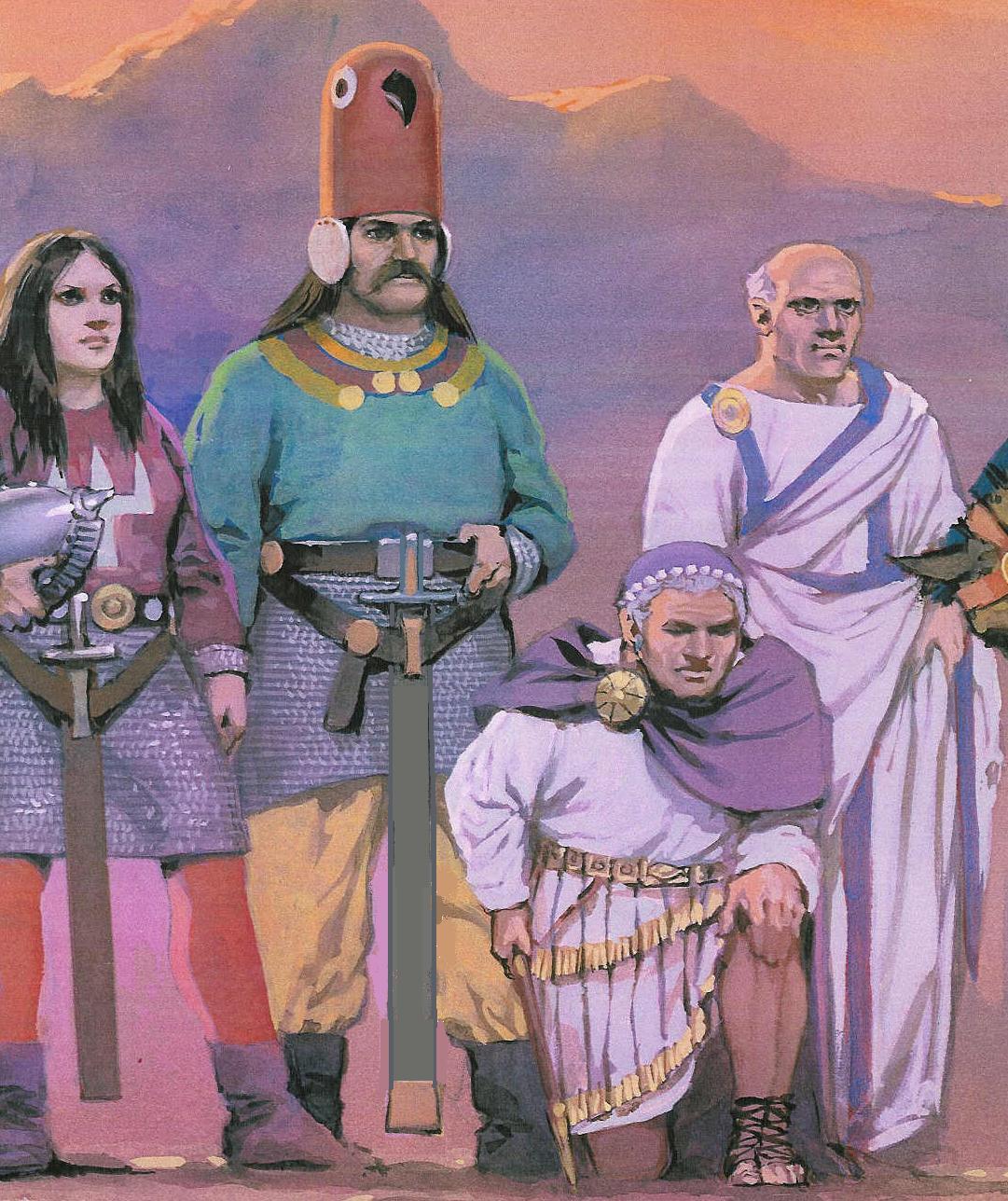

Emperor Valerian (r. 253-260 AD) (kneeling) and a Roman Senator (with Roman Toga at right) surrender to the army of Shapur in 260 AD. The Emperor and the Senator are escorted by an Iranian female warrior (left) and an officer of the Suren clan (with beaked red hat). Iranian women are reported by Roman sources as having fought alongside the ranks of the Sassanian cavalry (Farrokh, 2005, Plate A).

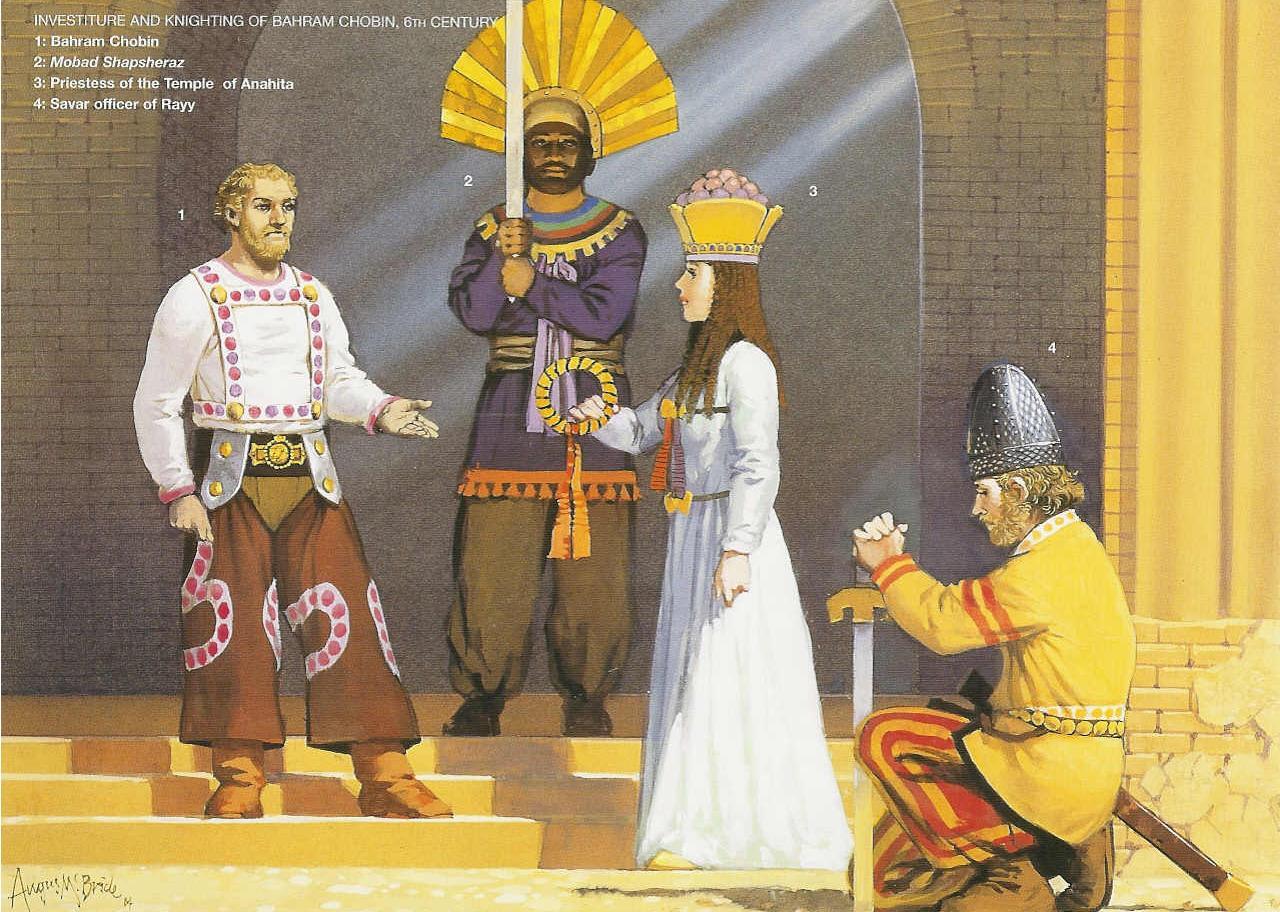

A priestess from the Temple of Anahita bestows the “”Farr” or divine glory upon Bahram Chobin after his spectacular victories against the Huns in the late 580s AD. Women play a crucial role in ancient Iranian theology and Zoroastrianism. (Farrokh, 2005, Plate E).

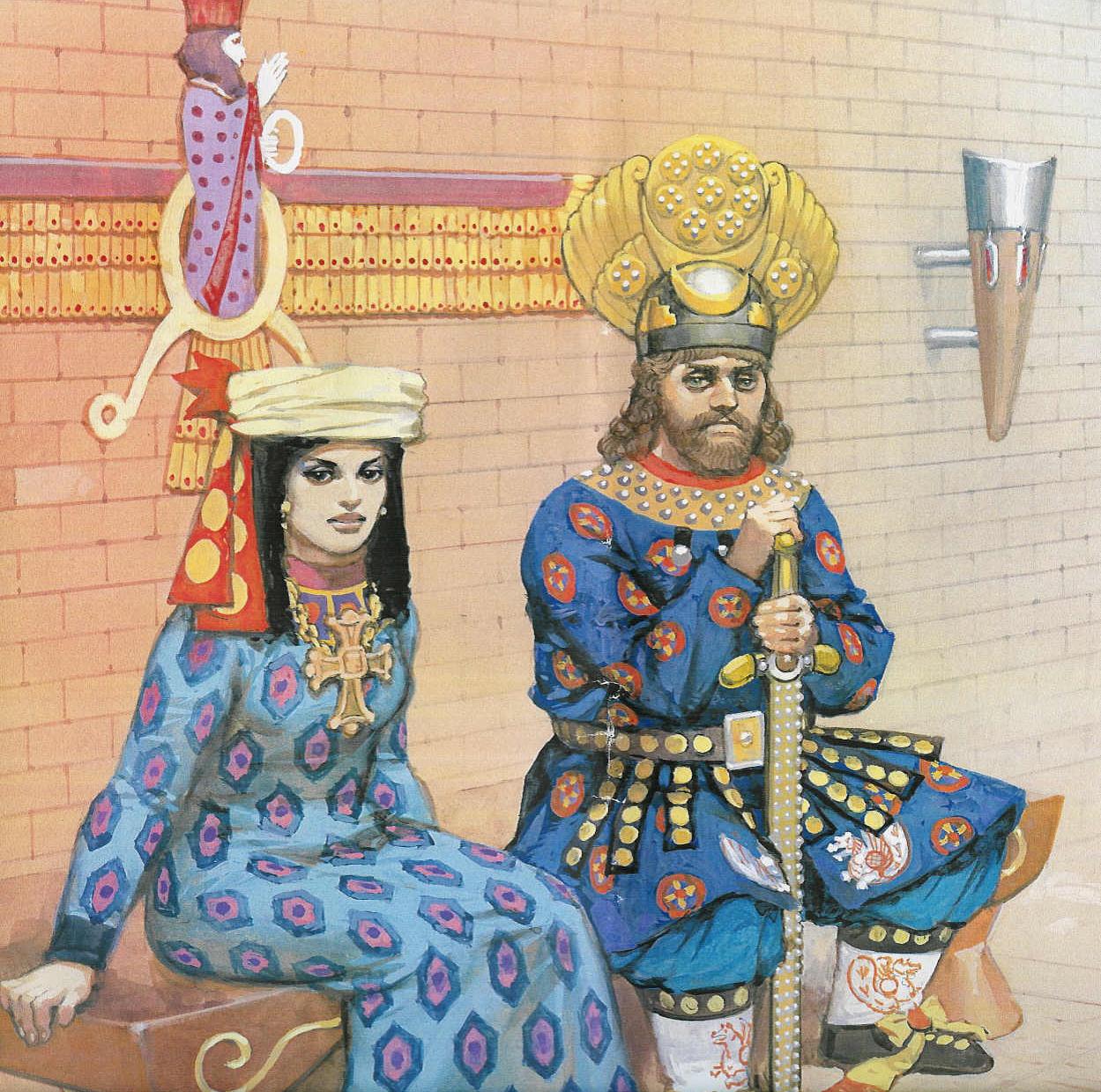

Princess Shireen (who was Christian) beside her husband and monarch, Khosrow II Parveez. Though Zoroastrian, Khosrow respected the Christian faith of his wife Shireen. In addition to Zoroastrians, Sassanian Persia had a large Christian as well as Buddhist population (Farrokh, 2005, Plate F).

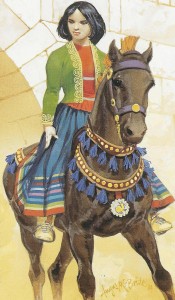

Princess Boran (lit. beautiful woman) at the site of Shiz in Azarbaijan. Boran was one of the last rulers of Sassanian Persia before the Arabo-Islamic invasions of 637-651 AD (Farrokh, 2005, Plate G).

As the Sassanian Empire collapsed to the invading forces of Islam from Arabia, a number of female resistance fighters rose to prominence, examples being Apranik (the daughter of General Piran), Negan, and Azadeh (who did much to prevent the invaders from entering northern Persia). As noted by Overlaet

“Daylaman

[in modern northern Iran] remained unconquered…until at least the 8th century AD…early Daylamite rulers even exhibited extreme anti-Arab attitudes and sought the restoration of the Persian Empire and the of the ancient religions” (1998, p.268).

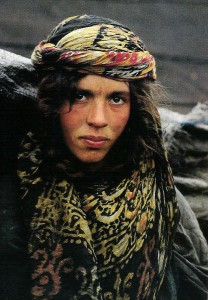

Girl from Chelsio region in Manzadaran. Many of the resistance fighters in the 600s and 700s AD from Northern Persia were women.

The exploits of Persia’s female warriors are recalled in the post-Islamic Shahnama epic of Ferdowsi. One sample quote states of the female warrior Gordafarid that:

“…as she was turning in her saddle, drew a sharp blade from her waist, Struck at his lance, and parted it in two.”

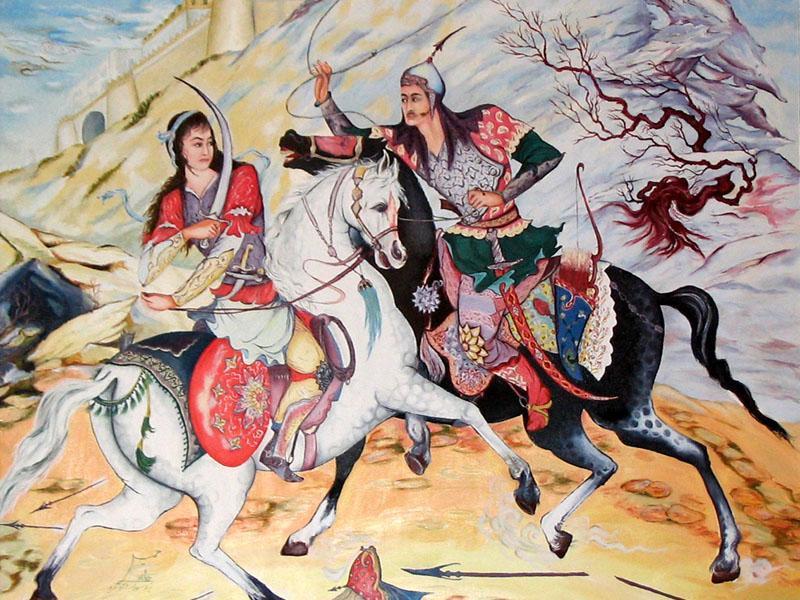

A Persian depiction of Gordafarid (at left) clashing with Sohrab.

The Post-Islamic Era

The last great revolt against the Abbasid Caliphate (816-837 AD) was led by Babak Khorramdin (798-838 AD) who from his base in Iranian Azarbaijan led a powerful resistance movement from 816-837 AD. This was the last great Iranian revolts which sought to re-establish the ancient Zoroastrian and other related ancient Iranian cults such as Mazdakism.

The Abbasid Caliphs had murdered Abu-Muslim of Khorasan (700-755 AD), despite the assistance he had afforded them against the Ummayad Caliphate (661-750 AD). This was due to the increasing popularity of Abu-Muslim of Khorasan among the Iranians.

The Caliphate was concerned with the possibility of an Iranian revival towards independence. The death of Abu-Muslim of Khorasan also made clear to the Iranian populace that their hopes for greater autonomy within the Caliphate were dashed. It was under these general circumstances that a major rebellion was to break out towards the northwest of Iran in Azarbaijan.

What is notable is the role of Banu, the wife of Babak Khorramdin during the revolt. Banu, alongside her husband Babak, led the 23 year rebellion against the Abbasid Caliphate from their base in Azarbaijan. Despite the eventual defeat of the movement by 837 AD, the memory of the Khorramdin uprising was to become etched in Iranian culture and folklore.

The Castle of Babak in the Kalaybar region in Iran’s Azarbaijan province. Every year people from Azarbaijan and all across Iran come to this fortress to commemorate the exploits of Babak and Banu.

The governess of Rayy (near modern Tehran) in a post-Islamic textile dated probably to the Dailamite dynasty (10th century AD) of northern Persia. The attire of the governess would not have been unlike that worn by Banu Khorramdin.

The Lurs, a west-Iranic people with strong links to the aforementioned Scythians of antiquity, have witnessed their womenfolk in active combat till recent times. The Zand Dynasty (1750-1794) from the Luristan region in Western Iran, often featured women in combat.

The founder of the Zand dynasty, Karim Khan Zand (1705-1779) and his warriors were often accompanied by their wives into battle. Lur female sharpshooters were instrumental in the rout and defeat of the invading Pathan tribes from Afghanistan in the 18th century. As noted by Izady:

“…The Afghan officers ridiculed the Zands for this, accusing them of hiding behind their women’s skirts” (Izady, 1992, pp.194).

Woman from Luristan dismounted from her horse. Traditional Lur women often engage in numerous equestrian activities and have been famed for their skills in sharp shooting from horseback (Photograph by Nosratollah Kasraian, 1990, Plate 117).

The Constitutional Movement (1906-1911)

One example of the importance of women in the political and social evolution of Iran can be seen during the constitutional revolution of Iran (1906-1911). The Iranian Constitutional Movement was the first of its kind in advocating human rights, equality and democracy in Western Asia. The aim of the Iranian Constitutionalists was to limit the absolute powers of the Qajar Shahs in favour of a democratically elected parliament.

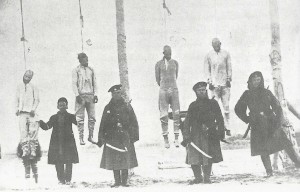

Constitutionalist nationalists fight under the Iranian flag in Tabriz in the early twentieth century. Iranian women fought valiantly alongside the men in their battle against the Qajar Royalists and their Czarist Russian allies.

The constitutionalist movement was brutally suppressed, an action which roused the anger of British Professor Edward Browne (1862-1926) who accused the British parliament at the time of tacitly approving Russian actions against western Asia’s first democratic movement. Russian Czarist forces and their allies bombed the Iranian parliament housing the democratic-minded representatives of the people of Iran.

Crushing Iranian Democracy by force: Czarist Russian Cossacks pose with their sabres drawn, in front of executed Iranian Constitutionalists. The Russian officer Colonel Vladimir Liakhov (1869-1919) holds the distinction of having bombarded the Majlis (Iranian parliament) in Tehran on June 23rd 1908.

During these epic moments in Iranian history, Iranian women were at the forefront of encouraging the constitutionalists to fight back against the Czarist Russians and their allies who were advancing towards Tehran. Morgan Shuster (1877-1960) who had been appointed by the Constitutional government to organize Iran’s finances (May-December 1911), has written about the crucial role played by the women of Iran. Below are some quotes made by Shuster (1912, pp.183-189):

“…the Persian women played the crowning act of the noble and patriotic part…the Persian women since 1907 had become almost at a bound the most progressive…in the world. That this statement upsets the ideas of centuries makes no difference. It is the fact…the women did much to keep the spirit of liberty alive…overnight became teachers, newspaper writers, founders of women’s clubs, and speakers of political subjects…”

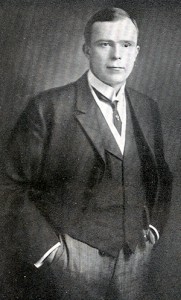

William Morgan Shuster (1877-1962) wrote about the exploits of Iranian women and their importance in ensuring that the ideals of the Constitutional Movement remained alive in Iran.

Despite the application of brute force, the ideals of the Constitutional Movement were never to be forgotten, thanks in large part to the women who had played a crucial (but as yet unappreciated) role in those events. Then as now, women have always been at the forefront in the promotion of human rights in Iran.

This short essay has endeavoured to expostulate upon the critical role that the women of Iran have played as engines of social and political change from antiquity to the present day.

The Persian Lioness as depicted by Dr. Musi Dorbayani. Iranians often refer to their women as “Shir-Zan” or Lioness in reference to their role in history and as champions of Human Rights.

Further Readings:

Cernenko, E. V. & Gorelik, M.V. (1989). The Scythians 700-300 BC. London: Osprey Publishing.

Chaqueri, C. (2001). Origins of Social Democracy in Iran. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Farrokh, K. (2005). Elite Sassanian Cavalry. Oxford: Osprey Publishing.

Farrokh, K. (2007). Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War. Oxford: Osprey Publishing.

Izady, M. (1992). The Kurds: A Concise History and Fact Book. Taylor & Francis.

Kasraian, N. (1990). Our Homeland Iran. Tehran: Sekke Press.

Mallory, J.P. (1989). In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology and Myth. London: Thames & Hudson.

Nafisi, S. (1955). Babak Khorramdin Delavar-e Azarbaijan [Babak Khorramdin, the courageous one/Brave one of Azarbaijan]. Tehran: Tabesh.

Overlaet, Bruno (1998). Regalia of the Ruling Classes in Late Sassanian Times: The Riggisberg Strap Mountings, Swords and Archer’s Fingercaps. In Riggisberger Berichte – Entlang der Seidenstrasse – Abegg-Stiftung, Riggisberg, pp.267-297.

Shamim, A.A. (1995). Iran dar Dorrey-e Saltanat-e Qajar (Chapp-e Sheshom) [Iran during the Qajar Monarchy Era (6th edition)]. Tehran: Moddaber.

Shuster, M. (1912). The Strangling of Persia. London: Adelphi Terrace.