The article below on the “Wings of Ahura Mazda” perpetuated in the design of the Armenian Khatchkar and other East Christian Crosses was written by Masis Panos and originally posted on March 8, 2015 in Understanding of Our Past.

=====================================================================

Introduction

Back in 2010 I had the opportunity to visit the Republic of Armenia. One of the places I visited was the Church of Surp Nshan (Holy Seal) in the town of Aparan in the Aragatsotn province. The Basilica, imbued with the piety of the worshippers that I saw on the Sunday I visited (21/11/10) had some very old stone sculptures in the vicinity. One of the sculptures that caught my eye had a Cross within a circle, with two figures to either side. I wrote about this in 2011. As mentioned in that article, it seemed in style to resemble the Sasanian Drafsh.

Aside from that example, I visited other sites in the Republic of Armenia that year (one of which was Dsegh mentioned in part 1) and in 2011 and encountered other examples of Crosses of a “Drafsh style” and further, were upon Wings.

What is the significance of Wings on such an emblem?

Its significance was clear to me from having read the book published by Osprey, “Rome’s Enemies (3) Parthians and Sassanid Persians” by Peter Wilcox with superb illustrations by the late Angus McBride.

Both on its cover and inside is shown a Plate by Angus with a Sasanian cavalryman carrying a Drafsh. It has Wings on it, said to represent Ahura Mazda, and is surmounted with a Sun upon a Crescent.

The Standard (Drafsh) is said to be of Fars, the heartland of the Sasanian dynasty.

Since my teenage years I had been aware of the Khatchkar and its own significance in Armenian culture, how even after the Armenian community would have gone, these edifices would somehow survive to testify of the culture that made it. Of course such edifices cannot resist well planned destruction as was meted out to the remaining Armenian Khatchkars of Julfa, now part of the Republic of Azerbaijan, by its own soldiery.

Seeing such early depictions of a Cross and ones with Wings, I began to realise that the “stereotypical” Khatchkar we Armenians think of, with its rich interlacing framing an ornate Cross with what to me looked like “flourishes” under the Cross, had evolved from these early depictions I had seen. The “flourishes” on the early examples were depicted as Wings.

Part 1

In August of 2010 I went with my cousin and his friends on a very quick, unplanned, tour around the Aragatsotn province, stopping at a site for ten minutes on average.

One of the places we visited the Church of Mughni.

Due to the tour being spur-of-the moment I only had my Mobile Phone to take photos with.

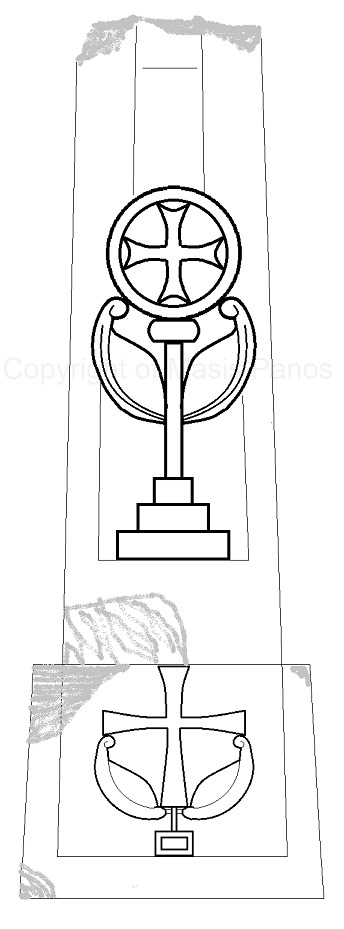

Below is a photo I took on my phone showing a section of a Pillar, outside the Church of Mughni.

Also a sketch I made of the Pillar, with the basic shape shown in grey with the Cross/Drafsh shown in black. Itself is upon a Pedestal which also has a Cross/Drafsh on it. Both are hewn from a dark coloured Tufa.

Later that year, in November, I visited the Lori province.

Later that year, in November, I visited the Lori province.

One of the places visited was Dsegh.

In this remote region we walked for a while and then came across an very old cemetery with a few ancient monuments still standing.

This one, according to the Armenian Ministry of Culture‘s website as well as the SOSCulture website, is dated to between the 5th – 7th centuries yet it has an inscription on its southern side dated to the 13th century in the name of an unchronicled “Vahram Mamikonian“. A Khatchkar nearby, dated to the 13th century, is said in both websites to have been sculpted by a “master Vahram”. Very confusing. There was a “Prince Mamikonian” who ruled the area in the 13th century. The reference both in the Armenian Ministry of Culture and SOSCulture websites to a “master Vahram” for the 13th century Khatchkar may be that it is dedicated to the Prince and what is insribed on the 5th – 7th monument may be attempting to link it to his family. Suffice to say, the monument that interests us is officially dated to between the 5th – 7th centuries.

The Dsegh Vartan monument (Source: Masis Panos)

The Dsegh Vartan monument (Source: Masis Panos)

Another view of the Dsegh Vartan monument (Source: Masis Panos)

Another view of the Dsegh Vartan monument (Source: Masis Panos)

This is a close up of the Cross of the base. Note how like the Pillar at Mugni, this Cross/Drafsh is on a three-stepped base and also has a “Latin” type Cross like the Pedestal of the Mughni monument.

Close up of the Dsegh Vartan monument (Source: Masis Panos).

Close up of the Dsegh Vartan monument (Source: Masis Panos).

Drawing of the Dsegh Cross (Source: Masis Panos).

Drawing of the Dsegh Cross (Source: Masis Panos).

In 2011 I again visited the Republic of Armenia.

One of the places I visited was Talin and its ancient Cathedral. There was also a small Chapel, dedicated to the “Mother of God” and was built either in 639 or 689 AD by Prince Nerseh Kamsarakan. Outside the Chapel there a monument, made from a dark Tufa, with the base restored, one of the sides depicts Mary with Jesus, surrounded by Angels.

The Nerseh Chapel (Source: Masis Panos).

The Nerseh Chapel (Source: Masis Panos).

Another view of the Nerseh Chapel (Source: Masis Panos).

Another view of the Nerseh Chapel (Source: Masis Panos).

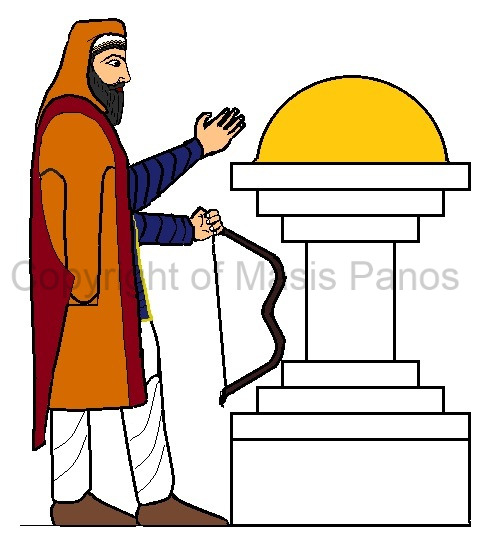

This may be a tomb as well as a monument, perhaps to Nerseh. On one side of the pillar is depicted a man, wearing a Kaftan or Chokha. His costume and manner is similar to the depiction of King Cyaxares at his tomb in Qizqapan (Surdash, Dukan district, As Sulaymaniyah province, Autonomous Kurdish Region, Iraq).

Depiction of King Cyaxares at his tomb in Qizqapan (Surdash, Dukan district, As Sulaymaniyah province, Autonomous Kurdish Region, Iraq) Source: Masis Panos).

Depiction of King Cyaxares at his tomb in Qizqapan (Surdash, Dukan district, As Sulaymaniyah province, Autonomous Kurdish Region, Iraq) Source: Masis Panos).

Hardly likely a fluke that they are depicted in a similar way, even if 1,200 years seperated them.

The Kamsarakan were of Parthian origin. An Iranian people. Cyaxares was king of the Medes, an Iranian people. What we see is Nerseh, proud of his roots and a wish to be depicted in a traditional manner.

There is more depicted on this monument outside the Chapel.

Talin Nerseh Chapel (Source: Masis Panos).

Talin Nerseh Chapel (Source: Masis Panos).

Close-up of the base of monument at Talin Nerseh Chapel (Source: Masis Panos).

Close-up of the base of monument at Talin Nerseh Chapel (Source: Masis Panos).

Below is a Stucco decoration with the name of a Sasanian King upon a Crescent on two Wings. The name, in Sasanian Pahlavi, is Shapur. There were four Kings with that name (Shapur I, II, III and IV). However, since Shapur II reigned the longest (309-379) it is likely from his reign.

Stucco decoration with the name of a Sasanian King upon a Crescent on two Wings (Source: CAIS).

Stucco decoration with the name of a Sasanian King upon a Crescent on two Wings (Source: CAIS).

A stucco roundel of a Ram, from the Sasanian era found in the ancient city of Kish in Iraq. The Ram was associated with the god of Victory, Verethragna.

Sassanian stucco roundel of a Ram, from the Sasanian era found in the ancient city of Kish in Iraq (Source: Pinterest).

Sassanian stucco roundel of a Ram, from the Sasanian era found in the ancient city of Kish in Iraq (Source: Pinterest).

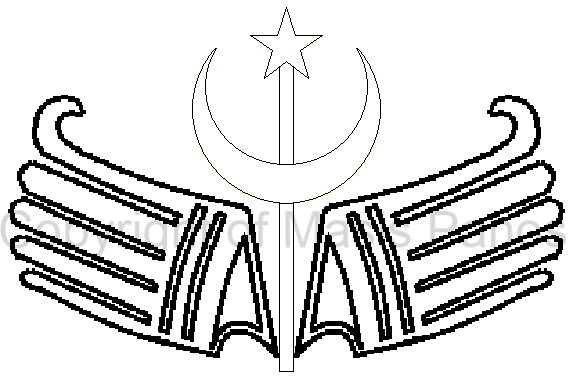

Below is a drawing I made of a Drafsh shown in a fragment of a Wall Hanging depicting figures in Persian Dress, dated to the late 6th–early 7th centuries AD. Made in the Eastern Mediterranean. Now housed in the Benaki Museum, Athens.

Drafsh depicted in a fragment of a Wall Hanging with figures attired in Persian Dress, late 6th–early 7th centuries AD (Source: Met Museum).

Drafsh depicted in a fragment of a Wall Hanging with figures attired in Persian Dress, late 6th–early 7th centuries AD (Source: Met Museum).

Drawing of the Drafsh in the fragment housed in the Benaki Museum, Athens (Source: Masis Panos).

Drawing of the Drafsh in the fragment housed in the Benaki Museum, Athens (Source: Masis Panos).

So the Wings represent Ahura Mazda, the “Standard of Fars” was totemic of the Sasanian dynasty and their firm adherence to the worship of Ahura Mazda above any other deity.

To try and make some dative sense of these examples:

The example of the “Stucco of Shapur“, above, dates either from:

240-272 (Shapur I) or 309-379 (Shapur II) or 383-388 (Shapur III) or 420 (Shapur IV)

The Wings still look like Wings, with some slight stylisation.

Khatchkar in vicinity of Church of Saint Gayane (Source: Masis Panos).

Khatchkar in vicinity of Church of Saint Gayane (Source: Masis Panos).

A Khatchkar from inside the Cathedral of Aruch, dated to between 661-682 AD. Note the similarity of the “Ribbons” under the Wings to the those on the Stucco Ram in Part 2.

Khatchkar from inside the Cathedral of Aruch (Source: Masis Panos).

Khatchkar from inside the Cathedral of Aruch (Source: Masis Panos).

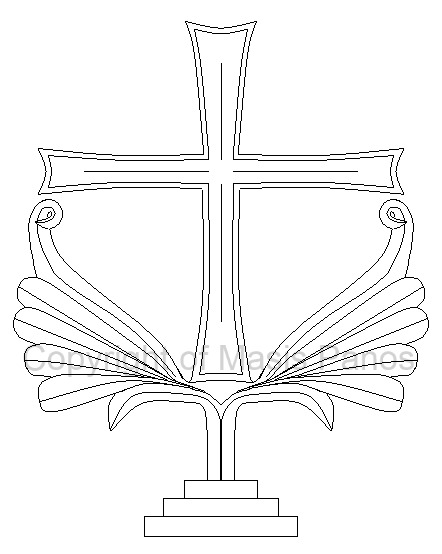

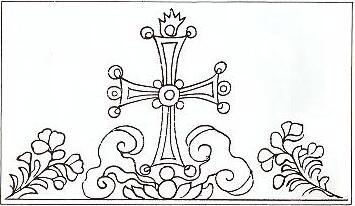

A Khatchkar from the Dadivank Monastery Complex. Said to have been founded by Saint Thaddeus in the 1st century, the actual complex was built between the 9th and 13th centuries. Note how the Wings have become stylised.

Khatchkar from the Dadivank Monastery Complex (Source: Masis Panos).

Khatchkar from the Dadivank Monastery Complex (Source: Masis Panos).

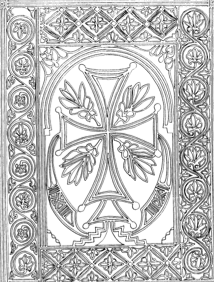

Three Khatchkars from the Noratus cemetry complex. Though it dates at least to the 10th century most of the Khatchkars date from the 16th century when the region was under the control of the Safavid Persian Empire. Note the elaborate designs, the Wings have become plant like.

Khatchkars from the Noratus cemetry complex (Source: Masis Panos).

Khatchkars from the Noratus cemetry complex (Source: Masis Panos).

What these examples show is a gradual stylisation of the Wings through the centuries as the original meaning of them is forgotten.

The East Syriac and Nestorian Churches also have examples of Crosses with “Wings” under them.

It is worth noting that these Churches had been for the most part developed and spread in the Sasanian Empire.

The Persian Cross in the Mar Thoma Church of North Paravur in Kerala (Source: Masis Panos).

The Persian Cross in the Mar Thoma Church of North Paravur in Kerala (Source: Masis Panos).

Above is what is known as a “Persian Cross” that is said to have been carved by Mar (Saint) Sabor and Mar Proth, two East Syriac Monks who arrived, by invitation, in the southern Indian Kingdom of Quilon in 825 AD. More can be read about them by clicking the link to the Wikipedia page to save digressing. This style, in a circle, is similar to the Cross outside the Basilica of Surp Nshan mentioned in the introduction and also on the Pillar in the vicinity of Mughni Church. An example is shown below of a similar Cross, this is from what is known as the “Main Church” of the ancient city of Petra.

Cross at the Church from Petra (Source: Nabataea).

Cross at the Church from Petra (Source: Nabataea).

Whilst the Aramaic was the language of Petra, the city, in its time under Christianity, was ruled by the Roman Empire. In the Cathedral of Etchmiadzin in the Republic of Armenia is a very early Christian sculpture, with Greek verses, showing the Chi-Rho within a circle.

The cross relief with Greek inscriptions at Etchmiadzin Cathedral (Source: Masis Panos).

The cross relief with Greek inscriptions at Etchmiadzin Cathedral (Source: Masis Panos).

Until the year 405 AD, when it got its own Alphabet, the Kingdom of Armenia used either Aramaic or Greek for its inscriptions. So this relic in Etchmiadzin might date no later than 405 AD.

The circle is likely a stylised Wreath. An example below shows a Roman Ivory carving, circa 350 AD with the Chi-Rho within a Wreath. In pre-Christian Greece and Rome the Wreath signified Victory. (Note also the two Doves to either side in both the Etchmiadzin and Ivory carving examples.)

Roman Ivory carving, circa 350 AD with the Chi-Rho within a Wreath (Source: Masis Panos).

Roman Ivory carving, circa 350 AD with the Chi-Rho within a Wreath (Source: Masis Panos).

In the same region of India where the “Persian Cross” is to be found, the Cross that is known as the Saint Thomas Cross is very common.

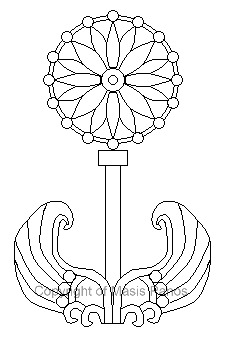

Saint Thomas Cross (Source: Public Domain).

Saint Thomas Cross (Source: Public Domain).

he Wings have become two Lotus Flowers in “a nod” to the dominant Vedic religion of the region as well as Buddhism. Also the Ribbon seen on the Stucco Ram and Cross of Aruch has become stylised.

Note also how it is upon a three stepped base, as seen in the Cross/Drafsh of Mughni and Dsegh in the Republic of Armenia in Part 1.

Though this Christian activity in Kerala seems to date from the 9th century it seems that the East Syriac Monks who would have come from Iraq, during the Abbasid Caliphate, took with them a style of Cross that had an long heritage in the region. Though it seems that after two hundred years after the fall of the Sasanian dynasty the meaning of the Wings had been forgotten.

As has been already mentioned, the East Syriac Church historically had been for the most part under the rule of the Sasanian Empire until the invasion by the Arab Caliphate. The Nestorian Church also found refuge in the Sasanian Empire and flourished within it, even spreading beyond it to the east.

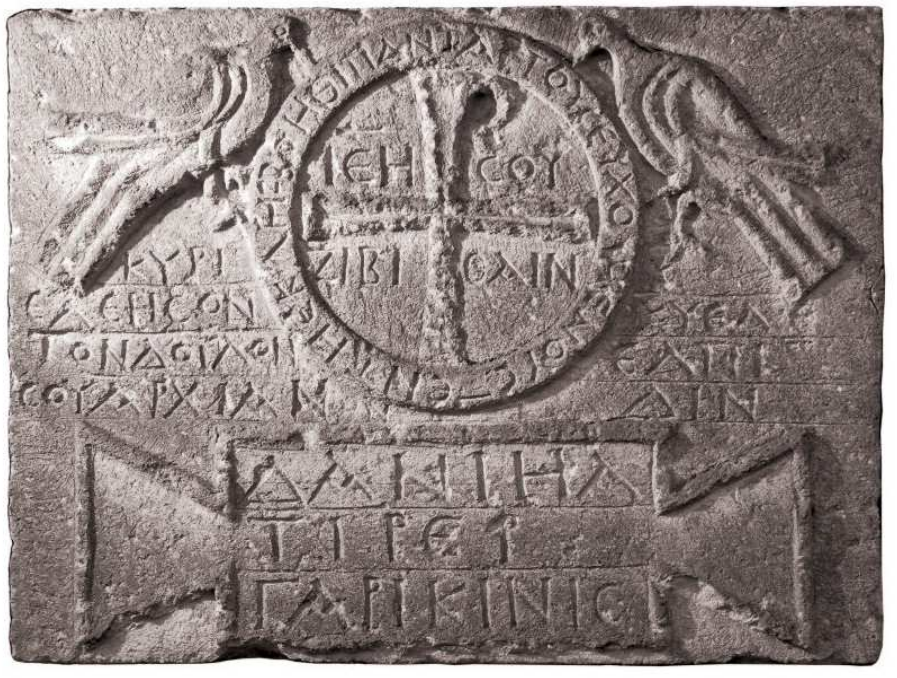

Below are some examples of East Syriac Crosses found by the excavation work carried out by the St. Louis Community College. This is a fragmented Stucco panel found in 1995 by Hadar Selou, 100 cm deep, at the site of Tell Tuneinir, near al-Hasakah in Syria.

Fragmented Stucco panel discovered at the site of Tell Tuneinir, near al-Hasakah in Syria (Source: stlcc.edu).

Fragmented Stucco panel discovered at the site of Tell Tuneinir, near al-Hasakah in Syria (Source: stlcc.edu).

The Cross is described “resembles a Medieval Khatchkar, Armenian stone cross” but from what is being demonstrated here, there is a reason for this similarity, this style likely originates from the region, during the Sasanian Empire, than been brought exclusively from Armenia.

Al-Hasakah is by the Khabur river, a tributary of the Euphrates. This would have been a border region between the Roman and Sasanian Empires from the 4th-7th centuries.

Another relic found in the excavations at Tell Tuneinir, found at the site of the monastery of Beth Kadeshy in 2001 by the St. Louis Community College.

Relic found in the excavations at Tell Tuneinir (Source: stlcc.edu).

Relic found in the excavations at Tell Tuneinir (Source: stlcc.edu).

Below is the description given:

“Broken fragments of a molded stucco footstone associated with the burial of a bishop or abbot in the center of the main entrance of the monastery.”

“Professor Michael Fuller interprets the image on the footstone as the Cross of Christ with a piece of fabric blown around its base. This would apply to the story of the resurrection of Christ and the empty burial shroud left behind in His tomb. The imagery is of the cross and resurrection.”

However, we see the precedents of this style of Cross. What is thought of as a shroud could be stylised Wings. Another find from the excavations:

The above is described as: “Painted cross fragment from Square 16, locus 02 (stone registry number 1162); discovered by James Walker during the 1999 field season. The surviving fragment measures 14.5 cm in length, 9.2 cm in width, and 1.1 cm thick. It weighs 284.4 grams.” (Source: stlcc.edu).

The above is described as: “Painted cross fragment from Square 16, locus 02 (stone registry number 1162); discovered by James Walker during the 1999 field season. The surviving fragment measures 14.5 cm in length, 9.2 cm in width, and 1.1 cm thick. It weighs 284.4 grams.” (Source: stlcc.edu).

Further afield, in modern China, is a monument created by the Nestorian community in 781 AD during the Tang Dynasty, known simply as the “Nestorian Stele”. Atop of the edifice is a Cross.

Sketch of the Nestorian Cross in China (Source: Masis Panos). Here is how it is described in “By Foot To China” by John M. L. Young, 1984: “The Cross sculptured on the famous Nestorian Monument-at Hsi-an-fu. It stands in the middle of a dense cloud which is symbolic of Muhammadanism, and upon a lotus, which symbolises Buddhism; its position indicates the triumph of the Luminous Religion of Christ over the religions of Muhammad and the Buddha. The sprays of flowers, one on each side, are said to indicate rebirth and joy.” Again, seeing the precedent of the “Standard of Fars” of the Sasanian era, the “dense cloud” could be stylized Wings.

Sketch of the Nestorian Cross in China (Source: Masis Panos). Here is how it is described in “By Foot To China” by John M. L. Young, 1984: “The Cross sculptured on the famous Nestorian Monument-at Hsi-an-fu. It stands in the middle of a dense cloud which is symbolic of Muhammadanism, and upon a lotus, which symbolises Buddhism; its position indicates the triumph of the Luminous Religion of Christ over the religions of Muhammad and the Buddha. The sprays of flowers, one on each side, are said to indicate rebirth and joy.” Again, seeing the precedent of the “Standard of Fars” of the Sasanian era, the “dense cloud” could be stylized Wings.

Below is a sketch of a stucco Cross found during the excavations at Failaka, a small island near Kuwait in 1989. The find site is known as “the southern Chapel”.

Sketch of a stucco Cross found during the excavations at Failaka (Source: pazhayathu.blogspot).

Sketch of a stucco Cross found during the excavations at Failaka (Source: pazhayathu.blogspot).

Some of the Christian communities, such as in Qatar, ended by the late 7th century but in the region of Kuwait it is thought to have survived into the 9th century. In the above example we can see how the Wings on this Cross have become stylized.

Conclusion

The type of Cross within a stylised Wreath may derive from the missionary activity from the Roman Empire. That Cross derives from the Chi-Rho monogram.

The use of the Ahura Mazda Wings on Cross emblems stems from those regions being under the rule of the Sasanian Empire. (It is more likely this type of emblemology was used to show loyalty to the Sasanian Empire than to show rebellion.). These two types, surviving examples to be found in the modern Republic of Armenia, to me demonstrates the political and military “tug of war” that took place over the Kingdom of Armenia from the 3rd to 7th centuries by Rome and Persia.

It is not exclusive to the Armenian region, as examples show this style of Winged Cross in the East Syriac communities of Iraq and their own activities into India and China.

So how could the “Wings of Ahura Mazda” be used on the Cross, associated with Jesus Christ?

Ultimately it may have been about showing the Magi and the Sasanian rulers that Jesus was about Goodness and was compatible with the Zoroastrian state religion.

Christians in the Sasanian Empire had to prove that they were not a “fifth column” for the Christian Roman Empire and so a use of a Zoroastrian emblem in depicting the Cross may have been a way of showing this loyalty. The part of Armenia that had come under Sasanian rule and also the numerous Christian communities of Iraq would have (and did) create such a “hybrid” motif as has been shown in this article.

After the fall of the Sasanian Empire, in the mid 7th century, these Christian communities would continue to make stone Crosses and use the Wings but gradually the meaning of the Wings was lost and their depiction became ever more stylised to the extent that modern research puzzles over their meaning, such as “Lotus Flowers” for the St. Thomas Cross or on the Nestorian Stele, or a “Shroud” in the Cross excavated at Tell Tuneinir in Syria.

Certainly in the case with the famous Armenian Khatchkar, stylisation went far indeed, as shown in a final photo below. This is a row of Khatchkars of various styles from the Kecharis Monastery in the Republic of Armenia.

The Monastery was founded by the Pahlavuni family in the 11th century. Note the Khatchkar on the left where the Wings have turned into arms, hands at the end hold Crosses.

Row of Khatchkars of various styles from the Kecharis Monastery in the Republic of Armenia (Source: Masis Panos).

Row of Khatchkars of various styles from the Kecharis Monastery in the Republic of Armenia (Source: Masis Panos).

This finding should not imply that the Wings of Ahura Mazda do not belong on a Christian edifice but that Armenians and East Syriac Christians can take pride in the rich heritage of their Christian culture and that the Sasanian Empire was not as anti-Christian as is often made out in the Christian propaganda that I have read, as an Armenian of the Armenian Apostolic Church (as for example in the legend of St. Sarkis).

Rather they were capable of coexistence.

A lesson indeed for the modern world.[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]