The article below (An Introduction to Persepolis) is by K.E. Eduljee in the Zoroastrian Heritage website.

=========================================================

Persepolis (Parsa in Persian) is located in the present southern Iranian province of Fars (Pars) and in ancient Persia. It was the seat of government and summer palace (Susa remained the winter residence) of the Persian Kings from the early 500’s BCE until its destruction and looting by Alexander of Macedonia in 330/31 BCE.

An artist’s impression of the Northeast view of Persepolis by K. Afhami and W. Gambke as it would have appeared (Source: Persepolis3D, K. Afhami & W. Gambke).

The site is popularly (and erroneously) known as Takht-e Jamshid meaning the Throne (or Palace) of Jamshid. Jamshid was a mythical king whose legend is part of folklore and he poet Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh.

While the present-day Persepolis / Parsa site is better known for the ruins of the royal palace / administrative complex, the site also contained the town of Parsa that existed adjacent to the palace complex, and which presumably housed the workers at palace complex, soldiers, artisans, crafts persons and other town residents. The town was surrounded by a fortification wall.

The Building of Persepolis

At the start of his reign around 521 BCE, Darius I, King of Persia (521-486 BCE) moved his capital from Babylon to Susa, where he started construction on a grand palace. No sooner had the palace at Susa been completed when Darius decided to build a palace complex in his native Pars. While the precise date when the extensive excavation work at the Persepolis site is not known, it is assumed to have started between 518 and 516 BCE.

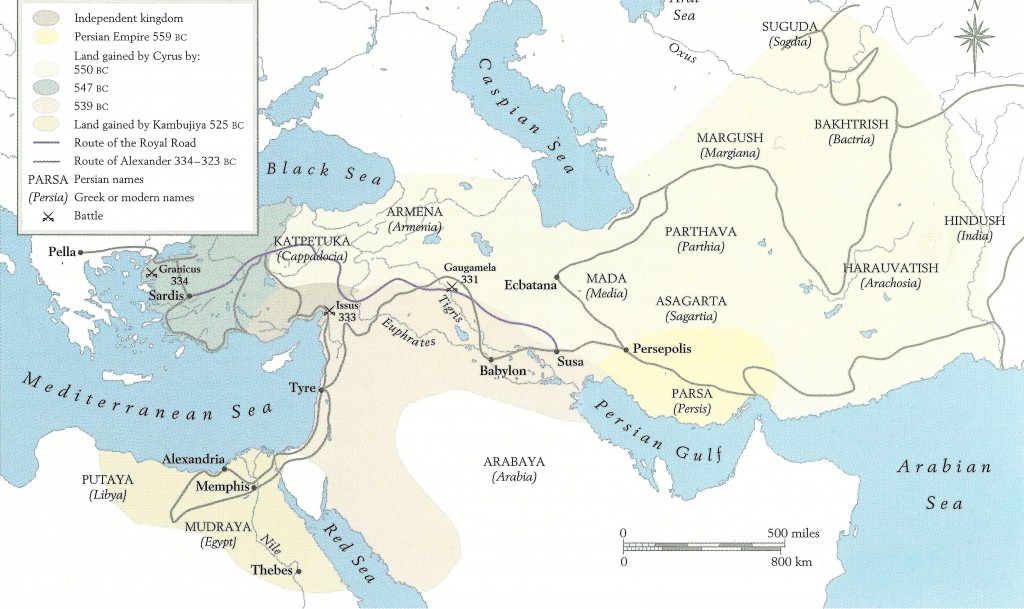

Map of the Achaemenid Persian Empire in c. 500 BCE (Source: Farrokh, page 87, 2007, Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War-Персы: Армия великих царей-سایههای صحرا–).

Map of the Achaemenid Persian Empire in c. 500 BCE (Source: Farrokh, page 87, 2007, Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War-Персы: Армия великих царей-سایههای صحرا–).

Darius lived long enough to see a part of his grandiose and ambitious plans executed. His son and successor Xerxes I (485-465 BCE) continued construction and the Persepolis we know was for the main part completed during Xerxes’ reign. A foundation inscription at Persepolis states:

“When my father Darius passed from the throne, I by the grace of Ahuramazda became king on my father’s throne. After I became king… I continued work and added to what my father had built.”

Work at Persepolis was completed a hundred years after its start during the reign of Artaxerxes I (464-424 BCE), Xerxes’ son and heir to the throne.

A view of the ruins of Persepolis form the hill behind the complex and looking west. In the background are the plains of the Marv Dasht basin (Source: Heritage Institute).

A view of the ruins of Persepolis form the hill behind the complex and looking west. In the background are the plains of the Marv Dasht basin (Source: Heritage Institute).

Location of the Site and Size

The site is located 60 km northeast of present day Shiraz, at an altitude of 1,800 meters on the eastern perimeter of the broad plain called the Marv Dasht basin. It is close to the small river Pulwar and the east side of the complex butts against the Kuh-e Rahmat or the Mountain of Mercy.

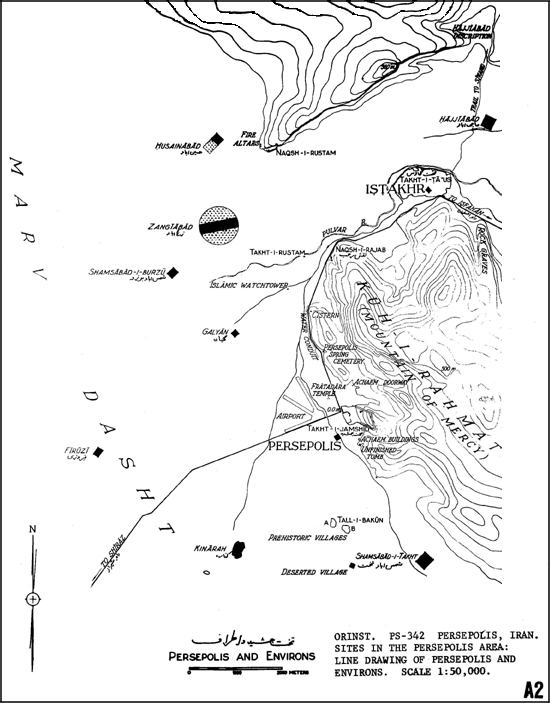

Sites and environs around Persepolis – Marv Dasht and Kuh-e Rahmat (Source:Heritage Institute & The Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago).

Sites and environs around Persepolis – Marv Dasht and Kuh-e Rahmat (Source:Heritage Institute & The Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago).

The Palace complex was brightly painted. At any time of the day and especially at twilight, the white-painted columns and gold-toned roof caps must have afforded a spectacular sight from afar.

The relatively small size of the ruins, belies the true scale of the township of Persepolis. The palace was surrounded by numerous dwellings. While there is no estimate of the population, it was in the thousands.

Site Map

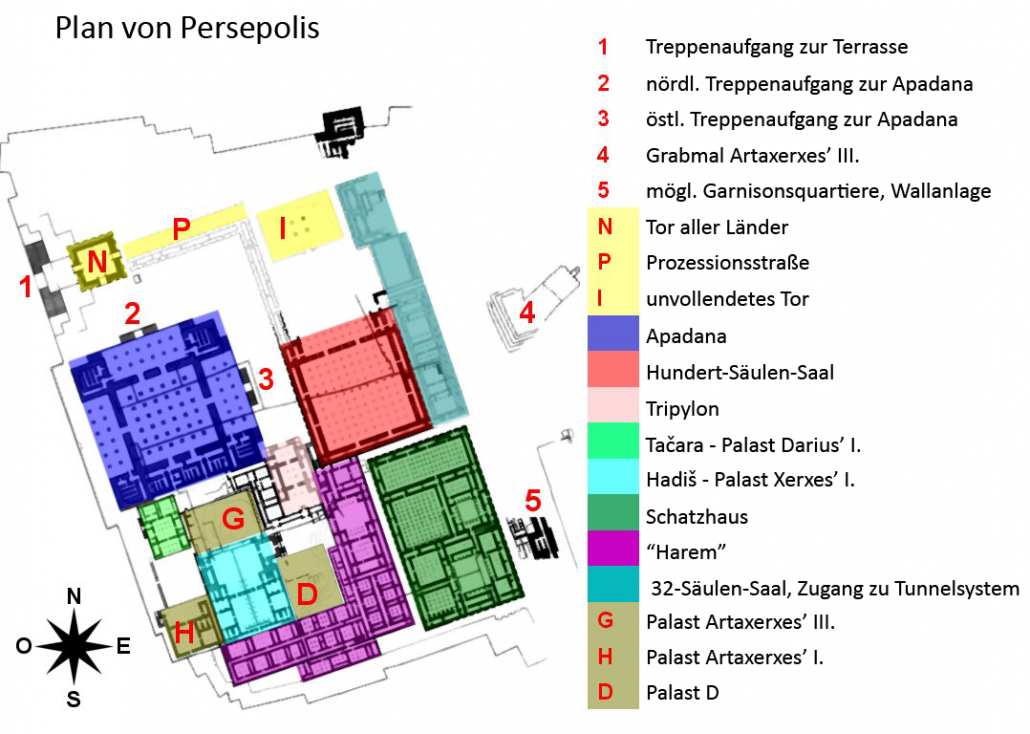

The palace complex is built on top of a 450 m long and 300 m wide i.e. 135,000 square meter terrace, raised between 7.5 to 18 meters off the lower slope.

The terrace is accessed by a double stairway that leads to the Gate of Nations (also called the Gate of Xerxes). To the left of the gate is the Apadana or audience hall.

The principle buildings are identified in the site plan on the right.

Identification of the Site

Locally, the site has traditionally been thought to be the palace of legendary King Jamsheed – therefore its local name, Takht-e Jamsheed (the Throne/Palace of Jamsheed). Less commonly, the site was also known as Chelminar (Forty-Minarets) or Sad-Sotun (Hundred-Columns).

In his travelogue, Italian and late-medieval Franciscan friar, Odoric of Pordenone, (also known as Odorico Mattiussi or Mattiuzzi and Odoricus), notes that (around 1320) he passed through Persepolis on his way to China. Odoric who had set out on his travels in 1313, calls the site Comerum – a name that Austrian scholar Alfons Gabriel would later point out was derived from the name of a nearby village – Kenareh. However, Ali Mousavi in his book, Persepolis, points out may also be a corruption of Kazerun – another village near Bishapur.

Site plan of Persepolis (Source: Public Domain).

Site plan of Persepolis (Source: Public Domain).

In 1472 or 1474, Venetian traveller Giosafat (or Josaphat) Barbaro visited the ruins of Persepolis and incorrectly surmized the ruins of Jewish origin. In his report, the Jornada (1606), Antonio de Gouveia from Portugal described Persepolis’ cuneiform inscriptions following his visit to the site in 1602.

The site was first identified as Persepolis, the capital of the Persian Achaemenid Empire in 1620-21 by Pietro della Vallee.

Jean-Baptiste Chardin (later to become Sir John Chardin) visited Persepolis on three occasions in 1667, 1673, and 1674. On his third visit, Chardin was accompanied by artist Andre Daulier-Deslandes who had previously published a panoramic drawing of the site. Chardin would argue that the site was not the ruins of a palace, but that of a temple. His argument was that palaces were built on river banks and not on hill slopes. Little did Chardin know of the Zoroastrian admonition not to pollute rivers. Chardin records the defacement and continued destruction of the ruins by successive Islamic era governments including Shah Abbas, the general Imam Koli Khan and even more so by Khan’s successor.

German naturalist, Engelbert Kaempfer visited the ruins in 1686 and was the first to call the inscriptions ‘cuneatae’ i.e. cuneiform.

Cornelis de Bruijn (also spelled Cornelius de Bruyn, 1652-1727), a Dutch traveller, visited Persepolis between 1704 and 1705. His account Reizen over Moskovie, door Persie en Indie published in 1711, contains exquisite drawings.

Around 1764 CE, Carsten (or Karsten) Niebuhr (1733 – 1815), a German mathematician, cartographer, and explorer, visited the ancient site at Behistun and made copies of the cuneiform inscriptions. He visited Persepolis in March 1765, and in three weeks and a half copied all the texts. His reproductions of the text engraved in rock faces were prepared so diligently, that few changes have been made to them since.

The Persian governor of Shiraz authorized a preliminary excavation in 1878.

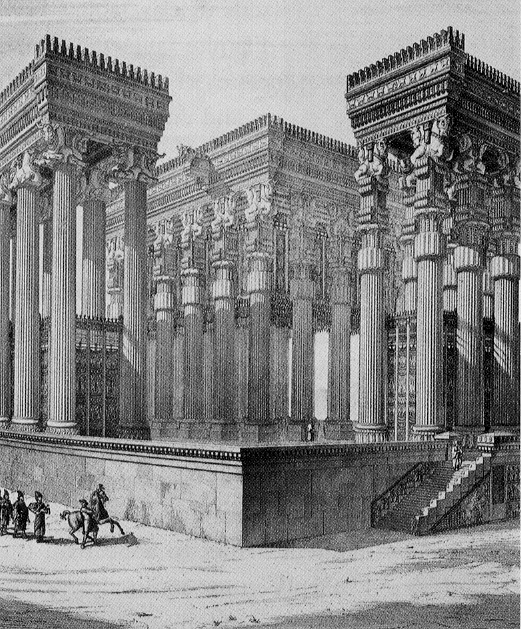

Reconstruction of Persepolis, by Eugene Flandin and Pascal Coste (19th century) (Source: Public Domain).

Reconstruction of Persepolis, by Eugene Flandin and Pascal Coste (19th century) (Source: Public Domain).

The Oriental Institute of Chicago commissioned the first thorough archaeological exploration headed by Ernst Herzfeld, then Professor of Oriental Archaeology in Berlin, and assisted by Fritz Schmidt. Their work at the site extended from 1931 to 1939. Together, Herzfeld and Schmidt uncovered on the Persepolis Terrace, the Eastern Stairway of the Apadana and the small stairs of the Council Hall. Herzfeld was accused of attempting to smuggle artifacts out of Iran and had to leave the country.