The Resket Tower (Persian:برج رسکت), officially dated to the 11th century and described as having been originally built at the site of a meteor impact, is located in the city environs of Sari located in Mazandaran province in northern Iran.

A view of the Resket Tower whihc has been recently (partially) restored (Photo: Alireza Zabini, Mehr News & Payvand News).

The Resket Tower is a cylindrical tower built of bricks and is topped with an (somewhat elongated) conical dome.The tower is approximately 15 meters at its base and stands at 18 meters in height. The tower’s interior features a cylindrical chamber.

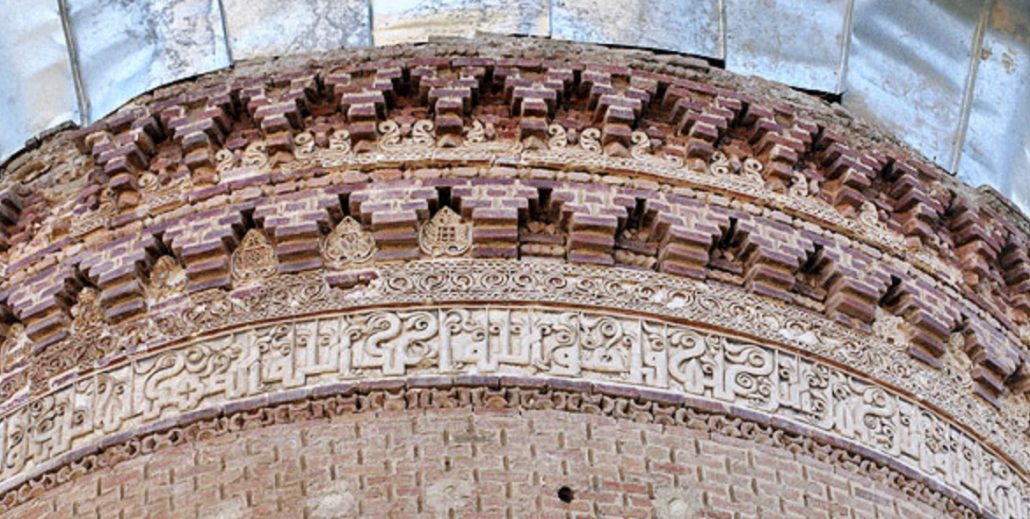

Close-up view of superimposed rows of V-shape brackets at Resket Tower (Photo: Alireza Zabini, Mehr News & Payvand News).

Interestingly this tower has both Sassanian (Middle Persian or Pahlavi) as well as early Kufic inscriptions. This would seem curious as the Sassanian empire had fallen by 651 CE, however northern Iran resisted the caliphates well into the 800s CE. The region (and the historical Azerbaijan in northwest Iran) retained strong cultural links with Iran’s pre-Islamic Sassanian past, even past the 800s CE which may explain the Pahlavi inscriptions on the tower.

A bottom-up view of the Resket Tower (Photo: Alireza Zabini, Mehr News & Payvand News).

The inscriptions on Resket Tower state that this is a tomb belonging to princes – and – of the local north Iranian Bavandid dynasty (651-1349). The Bavandids held sway in much northern Iran, known as Tabaristan at the time. As noted previously, much of Iran’s indigenous pre-Islamic identity was maintained, even as the Bavandids were reduced to vassal status.

A close-up view of the brickwork of Resket Tower (Photo: Alireza Zabini, Mehr News & Payvand News).

The observation below by Terry Graham sent to Kavehfarrokh.com on March 9, 2018 has been reprinted below for interested readers:

“So magnificent these inscriptions! Of course, the late conversion of the Caspian region is evidenced in this grand relic. It was in the following century that the Buyids poured out of neighboring Daylam, Gilan, to take over the caliphate and further Persianize it (given that the Abbasid caliphs themselves were Persian in every way but the language). Then farther west one had the Khurramiyya, who were a continuation of Mazdak’s movement, their very name reflecting both Mazdak’s and later Babak’s emphasis on ‘joy’ as an essential principle, expressed in the name of Mazdak’s wife, Khurram, as well. With her vigorously bold and eloquent defense of her martyred husband’s views, she was a model for Zaynab defending her brother in the time to come.

And of course, this was the era of the 9th-century Pahlavi books, representing an outpouring of work in that tongue far vaster than anything the Sassanians had written. The galvanizing of the non-literate Persians into the most massive writing activity in the world in both Pahlavi and Arabic (New Persian coming only a couple of centuries later) is one of the great wonders of world history in expressing the results of a revolution in Iran compared to which the Bolshevik one in Russia was no more than a tea party.”

Readers interested in reading more about this topic may consult:

- Babaie, Sussan; Grigor, Talinn (2015). Persian Kingship and Architecture: Strategies of Power in Iran from the Achaemenids to the Pahlavis. I.B.Tauris.

- Pope, Arthur Upham, ed., Phyllis Ackerman, assist. ed. A Survey of Persian Art from Prehistoric Times to the Present. Vol. 3, Architecture, Its Ornament, City Plans, Gardens, 3rd edited. Tehran: Soroush Press, 1977.

- Uqabi, Muhammad Mahdi, ed. Dayirat al-ma arif-i binaha-yi tarikhi-i Iran dar dawrah-i Islami, 381. Tehran: Awzahi-i Hunari-i Sazmani-i Tablighat-i Islami, 1997.