The term Dailamites may derive from the “Dimilii” who were a tribe of Medes who migrated into Northern Persia (roughly modern Gilan and Mazandaran today). Their descendants survive to this day in northern Iran.

These Medes would have come from what is roughly the northwest of Iran – they still exist as the “Dimili” among the ZaZa-Kurds of today who are believed by linguists to speak a variant of the Parthian Pahlavi language distinct from modern Kurmanji (Bahdenani and Sorani) spoken by the majority of modern-day Kurds.

Girl from the ZaZa clan in Turkey derived from the ancient Mede tribe of the Dimili.

The pace and timing of the Dimilii migrations are not exactly clear when this took place, as migrations were gradual, however we are certain that by the time of Sassanian king Khosrow I (6th century), the Dailamites were fully established in Northern Persia.

What is certain is that the Romano-Byzantines had a high respect for Dailamite skills in face to face combat (see writings of Agathias for example). They are reported as having fought with weapons such as daggers, swords, and javelins. They fought usually in the Caucasus against Turkic incursions into ancient Albania (modern Republic of Azerbaijan – different from Albania in Europe).

When the Sassanian Empire (224-651 AD) collapsed in the wake of the Arabian invasions it was in the north where Iranian resistance finally solidified. The one singular Arab failure in all of their otherwise spectacular successes in Iran, Byzantium, Central Asia, Syria, North Africa and Spain, was in northern Persia. The Dailamites solidly blocked Arab troops from entering northern Persia. As noted by Overlaet

“Daylaman remained unconquered…until at least the 8th century AD…early Daylamite rulers even exhibited extreme anti-Arab attitudes and sought the restoration of the Persian Empire and the of the ancient religions” (1998, p.268).

The main difficulty the Arabs faced was that they were facing very “European” terrain of mountains and dense forests in Mazandaran, Gilan and Rasht and were unable to stand up to the tough Dailamite infantry. The Arabs thought very highly of these warriors whom they called “Al-Hamra” (Red-faced ones) and recruited some of these for their own armies to fight in places as far away as Spain. The vast majority of the Dailamites however refused to bow to the authority of the Caliphs, even after the complete collapse of the Sassanians.

Local legends of Mazandaran report of female resistance leaders, one such figure being a certain Azadeh.

Girl from Chelsio region in Manzadaran. Many of the resistance fighters in the 600s and 700s AD from Northern Persia were women.

The Abbasids did manage to enter the region in 771 BC and stayed for nearly a century, but even then their authority proved sparse at best. During the reign of Harun al-Rashid (763-809 AD), many Muslin Shiites fled to the Dailamites to seek refuge from the persecutions of the Sunni authorities. The most notable of these were the Alids, who were either the descendants or followers of the Imam Ali, son-in-law of the Prophet of Islam, Muhammad. Prominent among these was a certain Sheikh Zayd, who began to win converts to Shiite Islam among the Dailamites. By the time the Buyid dynasty of the Dailamites seized power and took over much of Iran and Mesopotamia (including Baghdad), northern Persia was still non-Muslim, however Shiism was gaining ground.

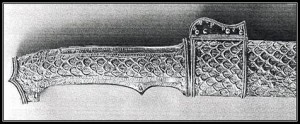

What is very interesting about Dailamite arms is that (despite being infantry), they were armed with the same weapons as the Sassanian Elite Cavalry (the Savaran). Note the late-Sassanian Dailamite sword handle and top of sheath below:

Dailamite sword found in northern Iran. This is of the late Sassanian type. The fact that the Dailamites were allowed to carry swords of the elite Sassanian cavalry is an indication that the Dailamites were among the most respected warriors of the Sassanian Dynasty.

Photograph of the locket-suspension section of a late-Sassanian sword of the late Sassanian Savaran cavalry by Dr. Manouchehr Khorasani, a leading authority of Iranian military hustory.

Further readings:

Khorasani, M.M. (2006). Arms and Armor from Iran: The Bronze Age to the end of the Qajar Period. Legat Verlag Publishers.

Overlaet, Bruno (1998). Regalia of the Ruling Classes in Late Sassanian Times: The Riggisberg Strap Mountings, Swords and Archer’s Fingercaps. In Riggisberger Berichte – Entlang der Seidenstrasse – Abegg-Stiftung, Riggisberg, pp.267-297.

Price, M. (2008). Iran‘s Diverse Peoples: A Reference Sourcebook. ABC-CLIO.