The report below by Souren Melikian originally appeared in the New York Times on November 4, 2011.

Readers with further interest in this topic may consult:

There are now a wide range of publications, foundations, think-tanks and academic programs that promote terms such as ‘Islamic Mathematics’, ‘”Islamic Art” , etc. in Britain, Europe, Pakistan, North America, India, the Far East, Indonesia, Central Asia, and the Arab world.

Professor Jalal Matini for example notes of the Saudi Arabian government’s display entitled “Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Yesterday and Today: A Cultural experience” on August 1, 1989 held in the Washington Convention Centre (in Washington D.C.) . The display was essentially relabeled artifiacts of Iranian origin as Arabo-Islamic (for more information consult Jalal Matini, “Persian artistic and literary pieces in the Saudi Arabian exhibition”, Iranshenasi: A Journal of Iranian Studies, 1989, p.390-404).

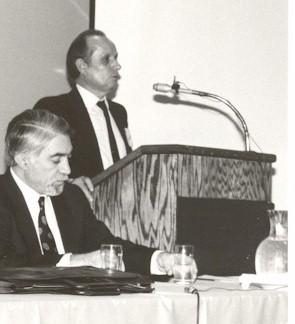

Professor Jalal Matini (standing at podium), the Chief Editor of the Iranshenasi journal flanked by the late Iranian poet and thinker, Nader Naderpour (seated at left) at UCLA. Professor Matini has addressed concerns against politically motivated terminology such as “Islamic Science” and “Islamic Arts” since the early 1980s. Professor Matini is the chief editor of the peer-reviewed Iranshenasi journal which published a review of Kaveh Farrokh’s second text Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War-Персы: Армия великих царей-سایههای صحرا-

Similarly, the Centre d’etudes Euro-Arabe of Paris, France, hosted a conference in November 1992 in which over 80 percent of artistic displays of Iranian origin were claimed to be of “Arab origin”. Yet another example of politically-motivated terminology is that of the 33rd International Congress of Asian & North African Studies in Toronto in which the Persian poetry of Jalal-e-Din Rumi was erroneously presented as “Arabic Literature”

The article below by Souren Melikian will prove of interest in lieu of the above discussion. Note that the posting below reproduces pictures that originally appeared in the New York Times article in addition to three pictures and descriptions that did not appear in the original article.

=====================================================================

Political bias often leads to absurd categorization. Even so, few among the arbitrary constructs adopted by the West as a result of 19th-century colonial attitudes can beat the meaningless concept of “Islamic art.”

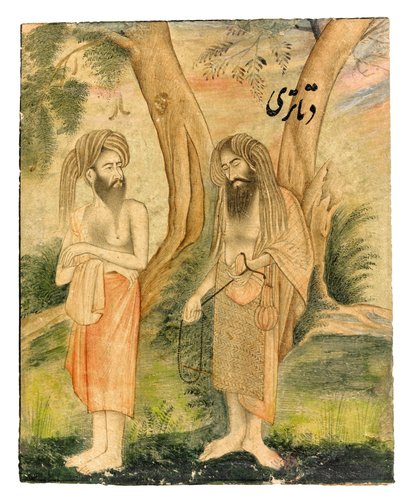

A Moghul painting in which a Hindu ascetic and a Muslim are seen together. It sold against the reserve for £12,500 (Souren Melikian, New York Times).

Its corrosive effect on academic thinking is matched by its counterproductive effect in the art market. By lumping together works of art that are not remotely related aesthetically or conceptually, it leads to a visual confusion that is unhelpful, to put it mildly.

Adding up the art of cultures far more diverse than those of Western Europe can disorient buyers. The Arab world, Iranian lands, Anatolian Turkey, the Islamicized areas of the Indian subcontinent, the Muslim communities of China — which are themselves highly diversified, from the Turkic-speaking Uighurs of Xinjiang to the northeastern Muslims of Han stock or those of the Xian region — have much less in common than, say, Britain, France, Germany and Spain. Anyone attempting to display together the paintings, sculpture and sundry objects of these European nations under the banner “Christian Art” or simply “Christianity” would risk being shown the door on the museum scene as in the auction arena. Not so where the “Islamic world” is concerned.

Consider the phenomenal jumble in the autumn sales. These began at Sotheby’s on the evening of Oct. 4 with a session focusing on a private collection.

Even the collection showed no aesthetic unity. A leaf from an eighth-century manuscript of the Koran reputed to be from the Hijaz and another in gold lettering on blue ground from a ninth-century manuscript likely to be from the east-Iranian province of Khorasan had nothing in common with the north-Iranian bowl painted with a bold stylized bird in the 10th-11th century. The bird bowl was in turn very different from the interesting Egyptian fragments of pottery painted with characters in golden enamels (traditionally cataloged as “lustre” enamels) that followed moments later.

The huge overestimation that affected all lots, compounded by visual inconsistency, proved lethal. The north-Iranian bowl sold, only just, for £18,750, or about $30,000, but the Egyptian fragments did not. The session ended up with only 13 lots out of the 41 offered managing to find takers.

Inventing the Middle East: The term “Middle East” was first invented by American Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840-1914). The term – Middle East – when examined in cultural, anthropological and cultural terms makes very little sense. Iran and Turkey for example are not Arab countries and in fact share a long-standing Turco-Iranian or Persianate civilization distinct from the Arabo-Islamic dynamic. Instead, the Turks and Iranians have strong ties to the Caucasus and Central Asia (Picture and description by Kaveh Farrokh).

The artificial character of the “Islamic” label came out even more spectacularly in the Sotheby’s Oct. 5 sale.

Putting together in the same session a Koran leaf from an eighth-century manuscript, a painted page torn away from a volume copied and illuminated in Moghul India around 1600-5, a large early 19th-century Iranian portrait of a lady of the court playing a string instrument, an ivory casket of so-called Siculo-Arabic make and a Chinese blue and white ewer ascribed to the Yongle period (1403-24) is not a recipe for aesthetic or intellectual coherence. The Koran leaf alone could be called “Islamic” in theological terms. Probably from Iran, it went for £37,250.

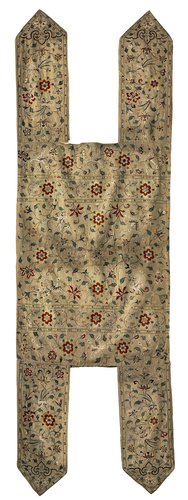

One of the great success stories at Christies was a brocaded silk cataloged as “Central Asia” that displays motifs pointing to early 14th-century Iran. It soared to £301,250 (Souren Melikian, New York Times).

But, the painted page from Moghul India hardly justified the qualifier. It was torn away from a unique manuscript executed at Allahabad, which preserves the Persian translation of a lost Sanskrit original. Commissioned at a Moghul court, it recounts the story of a Gupta emperor of the fourth to fifth century glorified into a Jain hero.

The text on the page reads like an excerpt from a Persian literary work mixing prose and poetry. It is reminiscent of the Iranian poet Saadi’s 13th-century collection of parables titled “Golestan,” or The Rosegarden, with the obvious intention of appealing to Moghul rulers, for whom Persian was the language of literature and court usage. This makes the rewrite of a Sanskrit original a quintessential literary product of the Indo-Persian culture that thrived on the subcontinent from the 12th century until 1836, when the British banned the use of Persian in official matters.

The highly original style of the painting blends the influences of Western European 16th-century prints brought to the Moghul court by Portuguese missionaries and of the century-old Indian artistic tradition. Add the Persian script called Nastaaliq from the hand of a highly skilled master and that again makes it a typical creation of the hybrid Persianate culture of Moghul India. “Islamic” does not begin to describe it. The page matched the lower end of the estimate at £25,000.

Mahan’s invented term “Middle East” was popularized by Valentine Ignatius Chirol (1852-1929), a journalist designated as “a special correspondent from Tehran” by The Times newspaper. Chirol’s seminal article “The Middle Eastern Question” expanded Mahan’s version of the “Middle East” to now include “Persia, Iraq, the east coast of Arabia, Afghanistan, and Tibet”. Surprised? Yes, you read correctly -Tibet! The term Middle East was (and is) a colonial construct used to delineate British (and now West European and US) geopolitical and economic interests. These same interests help promote the usage of terminology such as “Islamic arts and architecture” (Picture and description by Kaveh Farrokh).

The use of the “Islamic” label was even more absurd when referring to a painting representing Hindu women performing the Sivaite ritual of the anointing of the lingam. Artistically speaking, it is an archetypal Indian work. Were bidders nonplussed at its bizarre characterization? They sat on their hands. However, one of them did go for another Moghul painting in which a Hindu ascetic and a Muslim are seen together. It sold against the reserve for £12,500.

While the 12th-century Siculo-Arabic casket left bidders indifferent, Sotheby’s managed to find a taker for the Chinese blue-and-white ewer. It miraculously sold on a single bid for £181,250, despite its poor quality. Gilt copper mounts crowning the mouth and the tip of the spout suggest that it passed through Ottoman Turkey — although these, too, are not the best of their kind.

The auction house stretched the “Islamic” concept far enough to include Western European works of art. The lot illustrated on the catalog cover was described as a “Romanesque gilt bronze aquamanile, Germany, early 12th century.” While the date could be considerably later, there is no question that the bird-shaped object is Western in style. Sotheby’s statement that it is “in the form of a Senmurv” did not make it any more “Islamic.” The Senmurv is an Iranian mythical beast from pre-Islamic times and the bird does not even look like one: the Senmurv has the head of a wolf, not of a bird. The curious winged creature remained unwanted.

A blue-and-white porcelain ewer ascribed to the Yongle period (1403-24). It sold on a single bid for £181,250, despite its poor quality (Souren Melikian, New York Times).

The same lack of visual or conceptual consistency prevailed at Christie’s on Oct. 6. If the session had any greater merit, this was in underlining how different some objects can be even when produced in neighboring Islamic cultures around the same time. A 14th-century Syrian bowl painted with a lotus chalice done in a bold, rough manner was far removed artistically from the contemporary Iranian bowl, much more elaborate, to which Christie’s gave the traditional market label of “Sultanabad.” Respectively estimated £2,000 to £3,000 and £5,000 to £7,000 these, too, failed to sell. The estimates should have been slashed by half.

As in Sotheby’s sessions, the “Islamic world” concept at Christie’s encompassed Western works of art that were perhaps not selected with the utmost consideration for “Islamic” sensibilities. Somehow, a crusader sword did not appeal to bidders. Perhaps they did not put sufficient faith into the crudely engraved Arabic inscription suggesting that it had been picked up in the battlefield by Muslims beating back the European invaders. An Italian faience dish from Deruta, possibly painted in the 1530s with a spoofy rendition of a Turkish rider oddly holding a banner with Christian crosses, was similarly rejected.

Ironically, one of the great success stories was a brocaded silk cataloged as “Central Asia” that displays motifs pointing to early 14th-century Iran. Extraordinary well preserved, it is unique of its kind and it stood out in the midst of the disparate accumulation. The admirable textile with no visible connection to Islam soared to £301,250.

Not much concern for the preservation of cultural monuments came across at the sales.

Mahan and Chirol’s nomenclature (Middle East) provided the geopolitical terminology required to rationally organize the expansion of British political, military and economic interests into the Persian Gulf region. After the First World War, Winston Churchill (above – 1874-1965) became the head of the newly established “Middle East Department”. Churchill’s department again redefined “The Middle East” to now include the Suez Canal, the Sinai, the Arabian Peninsula, as well as the newly created states of Iraq, Palestine, and Trans-Jordan. Tibet and Afghanistan were now excluded from London’s Middle East grouping.The decision to affirm non-Arab Iran as a member of the “Middle East” in 1942 was to rationalize the role of British political and Petroleum interests in the country (Picture from Wikipedia, description by Kaveh Farrokh).

Sotheby’s cataloger observed that the painted page with a Persian translation of a Sanskrit original came from the only known manuscript of that work and coolly concluded that “thirteen leaves from the original manuscript (including the present page) were sold in these rooms July 11, 1972.” With the dispersal of its pages, any hope of ever publishing an edition of this important text for the heritage of Moghul India has vanished.

Dozens of major manuscripts from India, Iran and Turkey, ripped apart to sell their images piecemeal, have similarly perished. Some end up in museums, where they are proudly displayed as “miniatures,” a 19th-century misnomer that conveniently erases the memory of destroyed manuscripts. Orientalism has barely changed its colors in the interval.